“When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes

I all alone beweep my outcast state.

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries.

And look upon myself and curse my fate …”

— William Shakespeare, Sonnet 29

“If you believe you’re a poet, then you’re saved.”

— Gregory Corso

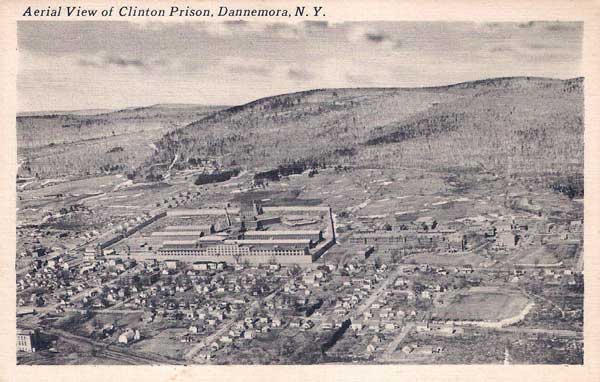

A plot to take over the city of New York, a cunning robbery with gang members co-ordinating their operation by means of portable two-way radios, thousands of dollars in loot, flight to Florida, living it up in the sun sporting a new zoot suit, betrayal by indiscreet and disloyal accomplices, arrest and a lengthy custodial sentence for having “placed crime on a scientific basis,” incarceration in Clinton Prison at age 17 — in print and across the internet, myth and misinformation, inconsistencies and contradictory accounts regarding the circumstances of Gregory Corso’s youthful crime and punishment are pervasive. Many of the falsehoods, it must be said, would seem to have originated with the poet himself. The origin of certain other errors and inaccuracies is unclear. To discover the true course of events, I contacted the New York State Archives in Albany, New York, asking their aid in researching court and prison records pertaining to Gregory Corso. The information on which I have based the following notes is a result of the kind help of personnel at the New York State Archives, to whom I am very grateful.

Before proceeding to official records of the actual events under discussion here, I would like to present a brief representative selection of some of the incorrect versions currently disseminated. That Corso was arrested and sent to Clinton prison in Dannemora, New York, at age sixteen is stated by several sources, including Carolyn Gaiser’s pioneering piece in A Casebook on the Beat, “Gregory Corso: A Poet the Beat Way,” Bruce Cook’s The Beat Generation, obituaries for the poet appearing in The Guardian, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times and The New York Times, The Dictionary of Literary Biography, as well as in biographical sketches of Corso on the sites of Poetry Foundation, The Academy of American Poets and The Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center. The same claim is repeated in a piece titled “Seven Inmates Who’ve Passed Through Dannemora,” appearing on the NBC News site, in Gadfly magazine, and in both Who’s Who in Twentieth Century World Poetry and The Continuum Encyclopedia of American Literature. A French web magazine titled L’autre likewise avers that Corso was imprisoned from his sixteenth to his nineteenth year, while another French web magazine, Salon-liternaute, states that Corso began his prison sentence at the age of fourteen years. More commonly, Gregory Corso’s age at the time of his arrest and subsequent incarceration is given as seventeen, as for example, in the Encyclopedia Brittanica, Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia of Literature, Modern American Poetry, 3a.m. Magazine, on Wikipedia and elsewhere. Equally in dispute is the nature of young Corso’s crime, with sources stating variously that he burgled a tailor shop (in order to secure a suit to wear on a date) or robbed a Household Finance office, either acting alone or as the mastermind of a walkie-talkie gang. Additionally, the nature of the merchandise taken in the burglary or the amount of money obtained in the robbery varies among sources, as do also the circumstances of Corso’s arrest and his incarceration in Clinton Prison.1

As stated earlier, Gregory Corso is himself the source of much of the confusion surrounding his crime, arrest, and sentencing, having at different times given dissimilar accounts of the events. Most famously, perhaps, there is the poet’s dedication to Gasoline, his second volume of poems: “to the angels of Clinton Prison who, in my 17th year, handed me, from all the cells surrounding me, books of illumination.”2 There is, of course, a distinction between one’s “17th year” and being 17 years of age, your 17th year begins immediately after your 16th birthday and ends when you have attained the age of 17. Most people, however, are unaware of this distinction and employ the expressions (17th year, 17 years old, age of 17) as meaning the same thing. Accordingly, it is somewhat unclear if in his dedication Corso means to indicate that he was 16 or 17 years of age. In a biographical note composed for The New American Poetry 1945-1960, Corso again writes that it was in his “17th year” that he committed an act of theft for which he was sentenced to three years in Clinton Prison.3 In this regard, Corso told Carolyn Gaiser that he was sixteen when the crime was committed.4 In an interview with Robert King in 1977, Corso repeated that he was sixteen years old at the time of the robbery of the Household Finance office, and that he entered Clinton Prison at the age of sixteen and left at age twenty.5 To complicate the confusion as to Corso’s age at the time of his arrest and incarceration, in an interview with Gavin Selerie, Corso states that he “did three years” in Clinton Prison, “from the beginning of seventeen years old to the end of nineteen.”6 And further to that confusion, in personal letters collected in An Accidental Autobiography, Corso writes “at the age of 17 I went to prison for 3 years;” “came out twenty,” and later writes of having “left prison at twenty.”7

As to the commission of the crime itself, the amount of loot obtained, and the circumstances of Corso’s flight and arrest, accounts of these are also at variance. Corso told Carolyn Gaiser that his walkie-talkie gang consisted of three: “each of the three boys took up an assigned position — one inside the store to be robbed, one outside on the street to watch for the police and a third, the master planner, in a small room nearby dictating the orders. According to Corso, he was in the small room dictating the orders when the police came.”8 When asked in an interview with Robert King to relate the circumstances of his youthful arrest, Corso replied that in the company of two other youths, he robbed a Household Finance office in New York City for the amount of 21 thousand dollars, fled alone to Florida, “bought a zoot suit,” but was informed on by his accomplices and subsequently arrested, tried and sentenced.9 Speaking to Gaven Selerie, Corso recounted much the same story, but stated that the amount of the haul was “twenty-six thousand dollars.”10 Corso has also remarked that the judge at his trial was unfavourably disposed to him for his use of technology (two-way radios) in the commission of a crime, having in this manner — in the view of the judge — put crime “on a scientific basis.”11 By way of contrast to these disparate accounts, an unattributed article titled “Biography of Gregory Corso” appearing on the PoemHunter website asserts that young Corso was sent to Clinton Prison for the far more modest crime of having broken into “a tailor shop and stolen an oversized suit to dress for a date.”12 This version of Corso’s fateful felony offence is confirmed or echoed by David S. Wills in his piece “The Life of Gregory Corso,” where Wills states that Corso was imprisoned “for stealing a suit.”13 Clearly, no single definitive version exists of any of the events, nor can a coherent account be inferred from the often contradictory information available.

The facts, then, as recorded on official forms of the State of New York Department of Correction, typewritten and signed, filed away these many years: the crime, conviction, and incarceration of Nunzio Corso (for such was his given name and thus his legal name). Nunzio Corso, alias “Sonny,” was arrested on April 1, 1948 for the crime of Attempted Larceny, 2nd degree, committed on March 29, 1948. (Having been born on March 26, 1930, Corso was therefore eighteen years old at the time of the commission of the crime. Larceny in the 2nd degree is charged when the value of the stolen property exceeds a certain amount of money; in the late 1940s this may have been 100 or perhaps 200 dollars.) More specifically, on 29 March 1948, Corso unlawfully entered an apartment, “via a key,” and there stole “rings, a watch, a pencil, currency and clothing” to the value of 230 dollars. He had no accomplices, and upon arrest (only 2 days after the robbery) confessed to the crime, explaining that his motivation for the robbery was that he “needed clothes.” Corso was held in jail until his trial on June 4, 1948, when at the Court of General Sessions, Judge Francis L. Valente sentenced him to be confined in a state institution under the jurisdiction of the Department of Correction for “a term of not less than two, nor more than three years.” To be subtracted from this indefinite sentence were the 65 days that since the time of his arrest Nunzio had already spent in detention. This was, in fact, Corso’s second felony conviction, the first having taken place when he was still a juvenile (13 years of age). He was then convicted on a charge of petty larceny for having stolen and sold a toaster. At that time, Corso was held in New York’s municipal jail, the Manhattan House of Detention, known colloquially as “the Tombs” for its Egyptian Revival architectural style. His confinement there was for him harrowing.

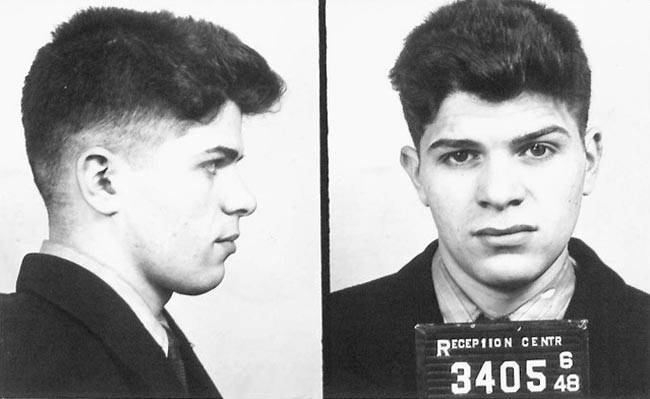

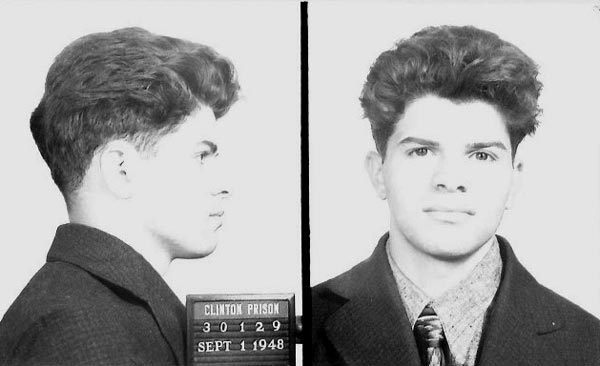

After sentencing by Judge Valente, Corso was initially sent to the Elmira Correctional Facility located in Chemung County, New York, which serves as a reception centre tasked with the intake and classification of offenders. Nunzio arrived at the reception centre on June 10, 1948. Upon entrance, personal clothing and property were taken away from him to be sent to his father, Fortunato Corso. These consisted of a two-piece suit and underwear, snapshots, and an address book. At the reception centre he was also required to list those immediate relatives with whom he would be permitted to correspond or from whom he would be permitted to receive visits. While there is no record of any visits, Corso did on July 23, 1948 receive from his father a package, containing candy, playing cards, toothpaste, cigarettes, a pipe, and pipe tobacco. A record of personal property later transferred from the reception centre to Corso at Clinton Prison includes the following items: 1 prayer book, 2 decks of playing cards, 2 letters, 5 books of matches, 2 tubes of toothpaste, 4 photos, 1 pipe, and 1 bar of soap. (Later, on November 8, 1948, from confinement at Clinton Prison, Nunzio would write a polite, neat, type-written letter to John Cain, the Chief Clerk of the Elmira Correctional Facility, inquiring as to the date set for a parole hearing and the status of certain personal belongings, “photos, snapshots, etc.” which had not, he writes, accompanied him from the reception center to Clinton. On the photocopy of Corso’s letter in my possession can be seen a handwritten note in pencil: “Inmate advised of parole date and given snapshots.”)

After 82 days at the reception centre in Elmira, on 31 August 1948, through the tremendous gates of Clinton Prison at Dannemora, New York, passed the slim, slight, (5 feet, 7 inches, 128 pounds), young Nunzio Corso, to live his days and nights confined within those heavy walls. In an article published in the mid-1950s, titled “Inside Dannemora Prison,” author Hal Burton notes that inmates of Clinton Prison have given it the ominous nickname of “Siberia.”14 Clinton Prison is, he states, “the bleakest, most boreal outpost of the New York State penal system … remote and frosted in winter by roaring blizzards.”15 The institution is, Burton writes, “the very epitome of a felon’s worst forebodings.”16 Similarly, in his book Gates of Dannemora, John L. Bonn writes of Clinton Prison as “this barred, narrowed place, enclosed within the gates of hell. The terrible hillside that they called the Big Yard, unspeakably ugly ….”17

Upon arrival at Clinton Prison, Corso was duly assigned a number (30129) and issued a coat, pants, shoes, socks, towels, cap, underwear, gloves, and shirt. There are no further records of his presence there until March 3, 1949, when a report from the Warden and a report from the Principal Keeper were sent to the Parole Board prior to Corso’s scheduled appearance before the board (to take place in July of that year). The report from the Warden states that: “He has not been reported for any infractions here to date. He is very young in his actions and he likes to fool around. It appears difficult for him to settle down either in his work or in his general behaviour. He is reported as being courteous, friendly and apparently resigned to his situation.” A similar characterization of the young felon is furnished in the report of the Principal Keeper: “Corso has only a fair work record here so far. He likes to spar with other inmates and spend his time kidding and clowning. He shows ability to work but he requires considerable supervision to keep him occupied.” A far more positive evaluation of Corso’s behaviour is provided by the Warden in a letter to the Morrell Plastering Co. of New York, N.Y. (who had apparently written to the Warden concerning Corso’s suitability as a future employee.) In his letter, dated November 2, 1949, the Warden writes: “His conduct since his incarceration has been excellent.”

Nunzio appeared before the Parole Board on July 21, 1949. Their recommendation was that he be held until January of 1950. On January 19, 1950, he appeared again before the board. On that occasion, their disposition was that he could be released from custody either on February the 1st of that year or in July. Records indicate that Corso received parole and was released from Clinton Prison on February 2, 1950. Upon release, he was provided with a ticket to New York City, a (one-time) state allowance of 20 dollars, plus 10 dollars and 85 cents in wages earned during his imprisonment. His parole expired on the 4th of April, 1951. He had, then, officially expiated his crime.

By his own account, Corso’s incarceration at Clinton Prison was for him a formative and decisive event. He has written that it was in prison he discovered literature and realized his calling as a poet. In his essay, “Some of my beginning and what I feel right now,” Corso states: “What would seem to most as a great injustice — being sent to prison in my seventeenth year, where I was the youngest inmate … proved to be one of the greatest things that ever happened to me. … In that time I read many great books and spoke to many amazing minds … Sometimes hell is a good place — if it proves to one that because it exists, so must its opposite heaven, exist. And what was that heaven? Poetry.”18 In his “Biographical Note” in The New American Poetry, Corso named some of the books and authors he had encountered in his prison reading. These included Fyodor Dostoyevski’s The Brothers Karamazov, Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, Stendhal’s The Red and the Black, as well as works by the English poets Thomas Chatterton and Percy Bysshe Shelley, and the poet and playwright, Christopher Marlowe.19 Elsewhere, Corso relates that while at Clinton Prison he devoured the 1905 Standard Dictionary, “every word … all the archaic and obsolete words.”20

Again, by his own account, in an interview, Corso states that while serving his sentence at Clinton Prison he was neither molested nor mistreated by the other inmates. This, he explains, was because he was Italian and “because I was young I had a kind of mascot status” among the Mafiosi.21 In another interview, Corso elaborates on his status among the prison’s powerful Mafiosi: “I was like a little mascot. That’s where I learned to be funny in life. Because I made them laugh, I was protected. … Man, their hearts were broken when I left prison. … Prison food was really awful, but I had good food because the Mafia guys got the food from the outside. They cooked steaks and everything, and I was always invited to eat.”22 Strange to say, Corso also relates that it was in Clinton Prison that he learned to ski: “I learned to ski in prison. … They had a ski lift going. I went down beautifully man, held myself right, and psshhh ….”23 The incongruous presence of winter sports facilities in this austere, forbidding, maximum security prison is confirmed by Hal Burton in “Inside Dannemora Prison,” where he writes that when temperatures at Clinton Prison plummet (sometimes to 40 below zero) “the winter sports season gets going full blast. There is a ski jump, a small bobsled run and a skating rink.”24

Other incidents or circumstances — some given wide circulation — relating to Corso’s time in Clinton Prison seem to me questionable or are clearly incorrect. One such widespread story is that while incarcerated at Clinton Prison, Corso occupied “the cell recently vacated by gangster ‘Lucky’ Luciano.”25 This unsourced biographical item has been embellished further with details of a private phone and self-controlled lighting in the cell, and even further elaborated upon with claims that Corso’s “cellmate was none other than mafia extraordinaire Lucky Luciano” and that it was Luciano’s personal library and personal “tutelage” that guided and inspired young Corso.27 Charles “Lucky” Luciano was incarcerated at Clinton Prison from July 1936 until May 1942 (leaving Clinton more than six years before Corso’s arrival). Luciano was in May of 1942 transferred to Great Meadow Prison in Comstock, N.Y. where he was to begin assistance to the Office of Naval Intelligence in operations advantageous to the U.S. war effort (for which services, following the war, Luciano’s sentence was commuted and he was deported to Italy, the country of his birth.)28 It seems improbable to me that Luciano’s personal library would have included Shelley, Marlowe, and Chatterton (more likely volumes by these authors or anthologies containing some of their work would have been available to Corso in the prison library) and it seems to me doubtful that any amenities that Lucky Luciano may have enjoyed in his cell would still be present and available to the fortunate occupant of Luciano’s former cell six years later. I have been unable to locate a source for these contentions, only accounts that treat them as fact.

Another incident alleged to have happened to Corso during the early days of his confinement at Clinton Prison is that of his initial attempt to declare himself unaffiliated with any Mafia family, insisting, instead, that he was “an independent,” as he is said to have put it. However, according to this account (widely disseminated on the internet) in the prison shower room Corso was subjected to an attempted rape from which he was saved only by the timely intervention of the powerful and fearsome mafia capo, Richard Biello, who reputedly remarked: “You don’t look so independent now, Corso.”29 Again, with regard to this story, I have been unable to locate a supporting source, only assertions that the event took place.

It is notable that the poets — Marlowe, Chatterton and Shelley — named by Corso as having catalyzed in him a realization of his own vocation as a poet, were all young rebels and heretics, proud outliers and prodigious inebriates of words. Thomas Chatterton (1752-1770), brilliant, reckless, rebel-poet was an impoverished outcast who died by his own hand before his eighteenth birthday, martyred by a materialistic society. Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593) was a shoemaker’s son, immensely gifted, seditious, heretical, unruly, a tavern brawler, slain while still in his twenties in a drunken bar fight (or assassinated by order of Queen Elizabeth I.) And, Corso’s particular poet hero, Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), wild iconoclast, ardent idealist, and passionate celebrator of love, liberty, and beauty, was drowned aged 29 in the Gulf of Spezia during a violent storm. All of these writers are romantic paragons, all precocious, all prodigies, all unyieldingly defiant of the strictures and constraints of their era — social, political and literary — all sacrificial geniuses and doomed martyrs to the lofty cause of Poetry. It is not difficult to see why teenaged Nunzio Corso, orphan and felon, damaged and outcast, yet drawn to beauty and moved by human suffering, would feel affinity with and draw inspiration from such figures.

I am intrigued by certain of the items Corso took away with him from the robbery for which he was convicted. One of the items, it will be recalled, was “a watch.” In an autobiographical article titled “The Times of the Watches,” Corso has written of his early and intense fascination with watches: “Throughout my childhood I’d do anything to get a watch.”30 In the article, he goes on to relate that the first thing he ever stole in his life was a watch, taken secretly from one of his foster fathers. When he first saw the watch, he writes, he was ravished by its beauty: “oh did my heart thrill, my breast beat, my brow sweat, my body itch. It was the most beautiful thing I ever saw.”31 Strangely, every watch he stole, bought or was given during his childhood was lost or stolen in its turn, the last of his watches being stolen from him while he was being held in the New York city jail prior to beginning his sentence at Clinton Prison. Although, clearly, a watch can be an item worth stealing for its cash value in a pawn shop or from a receiver of stolen goods, I wonder if Corso was not also tempted to take it for its irresistible beauty. The other curious item taken by Corso during the robbery in question was “a pencil.” A pencil! Among the rings, currency and clothing (and, of course, the watch) a pencil. How incongruous. How singular. What motive, I ponder, might he have had in stealing a pencil? I like to see the stolen pencil as a portent, prophetic both of Corso’s poetry and of his distinctive drawings, which have been compared to the drawings of Jean Cocteau for their “purity of line” and their “blend of the classical and the romantic.”32

In view of the discrepancies between the actual circumstances of Corso’s crime, his apprehension, his age at the time, and the poet’s later versions of the same events, what may account for the various dissimilarities? A likely explanation can be found, I think, in an attempt by young Nunzio Corso to disguise from his fellow inmates the banal and bungling nature of his crime and capture. By inventing a more elaborate and dramatic scenario, he could hope to preserve a minimum of dignity and maintain some measure of respect among his fellow felons who might otherwise despise him as an inept amateur. Corso’s later recasting of the actual events in response to interviews and in written biographical statements reflects, I believe, a psychologically necessary re-invention of himself. In the bleak midst of his misfortunes, he had — by way of personal salvation and out of ennobling aspiration — assumed the role of poet and so subsequently poeticized his crime and confinement, a species of self-mythologizing not uncommon among poets and artists. Corso may be said to have revised his personal history as a poet might revise a poem, thereby refining and enhancing it. In this way, his rather inglorious actual crime was transformed into one much more befitting a young poet.

I think, too, that the repeated claim by Corso that when sent to Clinton Prison he was in his “seventeenth year” rather than eighteen years of age, is not merely self-mythologizing but a poet employing the poetic device of hyperbole, an overstating for the sake of emphasis, in this case for the sake of poignancy. Corso’s slight exaggeration of his youthfulness at the time of his imprisonment serves to convey more intensely, more effectively, the piteous forsakenness of his situation as felt by him during that time. Some of this pathos would be lost if his actual age were given. The poet’s dedication of his collection Gasoline “to the angels of Clinton Prison who, in my 17th year, handed me, from all the cells surrounding me, books of illumination,” is in itself a poem. In a minimum of words it evokes in the imagination of the reader a potent, multilayered, deeply engaging story that would have been much diminished by literal fact. Even the alliterative effect created by the repetition of unvoiced “s” sounds (seventeenth, cells, surrounding) would have been lost.

Nunzio, as I have noted, was Corso’s baptismal and legal name. It was the name by which he was known to his father and brother and his many foster parents and to the authorities. He took the name of Gregory at his confirmation. That name had no official or legal status and was not used for any of the forms or documents pertaining to his trial, his incarceration in Clinton Prison or his parole. Gregory was a name he had chosen, selected from among numerous other possible names. In a similar manner, having chosen to be a poet, he chose to be identified by a new name, henceforth calling himself Gregory. We may say that in altering various prosaic facts to achieve a desired poetic effect, Gregory Corso was merely practicing the traditional alchemy of poetry, availing himself of the time-hallowed right of poets to exercise poetic licence.

1 ”Gregory Corso, A Poet the Beat Way” by Carolyn Gaiser in A Casebook on the Beat, ed. by Thomas Parkinson. New York: 1961, p. 268; The Beat Generation by Bruce Cook, New York: 1971, p. 134; The Guardian obituary, 20 January 2001; New York Times obituary, 19 January 2001; Los Angeles Times obituary, 19 January 2001; “Gregory Corso” by Marilyn Schwartz in The Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 16, Farmington Hills, MI: 1983, pp. 118-119; Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/gregory-corso; The Academy of American Poets https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/gregory-corso; Harry Ransom Research Center http://norman.hrc.utexas.edu/fasearch/pdf/00190.pdf; NBC News, “Seven Inmates Who’ve Passed Through Dannemora” by Jon Schuppe, 8 June 2015 https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/new-york-prison-escape/six-notorious-inmates-whove-passed-through-dannemora-prison-n371641; “Gregory Corso: Last of the Beats” by David Dalton, Gadfly 2001 http://www.gadflyonline.com/home/best_of_2001/THURSDAY-BOOK/BOOK-CORSO.html; Who’s Who in Twentieth-Century World Poetry ed. by Mark Willhardt & Alan Michael Parker, London: 2000, pp. 69-70; Continuum Encyclopedia of American Literature ed. by Alfred Bendixen & Steven R. Serafin, London: 2003, p. 221; “Le Tempo Beat du Quatrieme Mousquetaire Gregory Corso” in L’autre https://www.lautrequotidien.fr/articles/2017/9/18/gregory-corso; “Gregory Corso” in Salon-linternaute http://salon-litteraire.linternaute.com/fr/c/search?q=gregory+corso; “Gregory Corso American Poet” Encyclopedia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/biography/Gregory-Corso; Merriam-Webster Encyclopedia of Literature ed. by Kathleen Kuiper, Springfield, Mass: 1995, p. 273; “Gregory Corso” Modern American Poetry http://www.modernamericanpoetry.org/poet/gregory-corso; “Gasoline — the imaginary & the pure” by Paul Stubbs, 3:AM Magazine 11 March 2010 https://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/gasoline-the-imaginary-and-the-pure-gregory-corso/; “Gregory Corso” Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregory_Corso

2 Gasoline by Gregory Corso, San Francisco: 1958, p. 3.

3 The New American Poetry, ed. by Donald M. Allen, New York: 1960, p. 429.

4 Carolyn Gaiser, op. cit.

5 The Whole Shot: Collected Interviews with Gregory Corso, ed. by Rick Schober, Arlington, MA: 2015, p. 104.

6 The Riverside Interviews: Gregory Corso, ed. by Gavin Selerie, London: 1982, p. 23.

7 An Accidental Autobiography: The Selected Letters of Gregory Corso, ed. by Bill Morgan, New York, 2003, p. 122, p. 55, p. 19.

8 Carolyn Gaiser, op. cit. pp. 268-69.

9 The Whole Shot, op. cit.

10 The Riverside Interviews, p. 22.

11 See Gavin Selerie, Robert King et al.

12 ”Gregory Corso Biography” PoemHunter https://www.poemhunter.com/gregory-corso/biography/

13 “The Life of Gregory Corso” by David S. Wills, Beatdom Volume 2, Dundee: 2008, p. 49.

14 “Inside Dannemora Prison” by Hal Burton, The Saturday Evening Post, December 29, 1956, p. 11.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Gates of Dannemora by John L. Bonn, New York: 1951, p. 276.

18 “Some of my beginning and what I feel right now” by Gregory Corso in Contemporary American Poetry ed. by Howard Nemerov, Voice of America Forum Lectures, 1965.

19 The New American Poetry op. cit.

20 The Riverside Interviews, op. cit.

21 Ibid.

22 The Whole Shot, p. 104.

23 Ibid. pp. 104-05.

24 “Inside Dannemora Prison,” p. 67.

25 See, for example, https://www.ndbooks.com/author/gregory-corso/, the Wikipedia entry on Gregory Corso, and myriad other online sites.

27 “Alumnus resurrects on the road journey of lesser Beat poet” by Josh Schonwald, The University of Chicago Chronicle, Vol. 28, No. 3, October 23, 2008. http://chronicle.uchicago.edu/081023/beat.shtml

28 See The Encyclopedia of American Prisons by Carl Sifakis, N.Y. 2003; “Dannemora Gets Lucky” by Michael Berdan, Adirondack Life, August 2007, www.adirondacklifemag.com/blogs/2012/11/28/dannemora-gets-lucky/, “When Lucky was locked up” by Thomas Hunt, The American Mafia: The History of Organized Crime in the United States, mafiahistory.us/a004/f¬_prisonlucky.html, The Mafia at War by Tim Newark, N.Y. 2012, p. 269, 270-71; The Luciano Story by Sid Feder & Joachim Joesten, N.Y. 1994, p. 190.

29 See Wikipedia and PoemHunter op.cit and “The Song of Gregory” colhernaboca.wordpress.com/2015/03; “Gregory Corso, um improvavel poeta beat” muralcultural2.blogspot.com/; “Gregory Corso: El angel de las Musas www.festivaldepoesiademedellin.org/es/Diario/Corso.html; “The Beat Poets of the Forever Generation: Gregory Corso” http://thebeatpoetsoftheforevergenera.blogspot.com

30“The Times of the Watches” by Gregory Corso, Cavalier, December 1964, Vol. 14, No. 138, p. 36.

31Ibid. p. 92.

32 Beat Art by Joseph Masheck, Butler Library, Columbia University, N.Y. 1977, p. 15.

Leon Horton says

Excellent, informative piece on one of the most interesting but little understood Beats. Thank you.

Gregory Stephenson says

I’m so sorry but I only just now discovered your kind comments. Thank you so much! Gregory

Jerome Poynton says

Curious if Herbert E. Huncke and Gregory’s time overlapped at Clinton?

Gregory Stephenson says

Egad, I just now read your interesting question. I don’t think so. I remember an interview where Huncke expresses some surprise about Corso’s imprisonment at Clinton. Nevertheless, an intriguing idea. Best to you, Gregory

Gregory Stephenson says

Thank you so much for your kind comments! Gregory

Bob Rosenthal says

Great article Gregory Stephenson! I have heard and read so many of these differing stories that I am glad to have one clear picture.

I was walking Gregory Corso to the bank , going through Union Square. Gregory stopped and pointed up to the stature of Lincoln and remembered being taken with fellow orphanage kids to see this statue.

Gregory Stephenson says

Thank you so very much, Bob! I think I must have neglected to reply to these encouraging and generous comments when you wrote me. Very interesting anecdote. I love it. Very best to you, Gregory

Richard Modiano says

Excellent research Gregory Stephenson, a valuable contribution to Beat history and biography.

Gregory Stephenson says

I am embarassed that I did not see your very kind comment before this instant. Thank you very much, indeed!

All best, Gregory