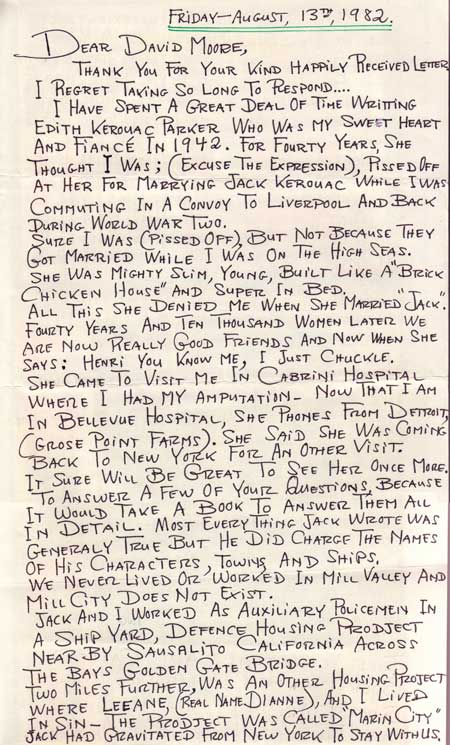

Henri Cru was one of the friends that Jack Kerouac met at Horace Mann School, New York, in 1939. Their friendship sustained for many years, and Cru featured as a character in several of Kerouac’s books. He was the model for “Remi Boncoeur” in On the Road and “Deni Bleu” in Visions of Cody, Lonesome Traveller, Desolation Angels, Vanity of Duluoz and Book of Dreams. After a working lifetime of sailing the seas as a marine electrician, Henri retired to live in Greenwich Village, New York, where he continued to pursue his interest in horse-racing. Cru emerges as a shadowy character in the various Kerouac biographies, probably because he seems not to have been interviewed by the researchers concerned. I am indebted to Edie Parker for putting me in touch with Henri Cru in 1982. Henri was then in Bellevue Hospital, New York, recuperating after having his left leg amputated as a result of diabetes. In answer to my questions, letters followed from Henri, carefully drafted in capital letters in the style described by Kerouac. Henri Cru sadly died in 1992. This interview is based on our correspondence between 1982 and 1986. I should also like to thank Henri, his sister Yvonne Perkins, nephew Geoffrey Moore, and Russell Lambariello for their patience and help.

DM: Can you begin by telling me something of your family, and when and where you were born?

HC: I was born on April 2, 1921 in Williamstown, Massachusetts, on the site of what is now the Williamstown Playhouse.

DM: So Kerouac had changed your father’s profession when he wrote in On the Road that he was “a distinguished doctor who had practiced in Vienna, Paris, and London”? [1]

HC: Yes, that’s correct. My father was never a medical doctor, although he was a Ph.D. What puzzles me is how come Professor Cru had such a dumb-bell for a son.

DM: And it was during this time that you first met Kerouac?

HC: Yes, Jack came to Horace Mann in 1939 from Lowell, Mass as a ringer, to play football. It was a very expensive school with an excellent scholastic reputation. Jack and the rest of the first team got a big discount on their tuition, because they enhanced the school’s football reputation. When I first saw him on the field he appeared to be a French-Canadian who had some American Indian blood. He was short, but built like a weight-lifter. He was also fast, and held his own with the big boys. He arrived at Horace Mann with a football uniform that looked like he’d bought it at an Army/Navy Store during World War One. It was a second-hand khaki uniform, worn thin from years of use. He wasn’t the best player on the team, but he was better than any player that was rated second. He first impressed me as being a country boy, but he approached me in a most friendly fashion and tried to talk to me in French. I had been born into a French family, and Canadian French is hilarious to a Frenchman. But he was a real good kid and we became close friends. He certainly helped me all he could with my English in school. I believe that deep inside Jack wanted to become a real Frenchman, and he struck up a real long-lasting friendship with me.

I made half a dozen other good friends at Horace Mann. I was very close with William La Cava, the son of Gregory La Cava, the motion picture producer. [2] A fellow named Ditmar’s parents had a palatial home where I was regularly invited to parties.

DM: Can you tell me something of your wartime activities?

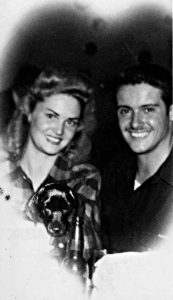

DM: I believe it was around this time that you met Edie Parker, who later became Kerouac’s first wife?

HC: Upon returning to New York I met Edith Parker at the West End Café. When it came time for the joint to close I politely said goodnight and how happy I was to have met her. She responded: “Aren’t you going to take me home?” to which I replied: “I don’t believe your boyfriend will think too highly of that”. Edith retorted: “Hell! He’s not my boyfriend, he’s my brother!” — who turned out to be a splendid fellow. Regrettably, he died in World War Two. Edith wore a lot of sweaters, was built like a brick chicken-house and had legs that looked quite long because she wore high-heels most of the time. Besides the fact that she was a great sport and loads of fun, I was most attracted by her. I don’t think it would be in very good taste for me to dwell on what happened shortly thereafter … [3]

One thing I remember vividly was that while we were walking down to the movies at 110 Street, she suddenly encountered friends of hers and introduced me by saying: “I would like you to meet my fiancé Henri Cru”. When we moved on I jumped up a foot off the sidewalk and hollered out “Your WHAT?!” She very calmly explained that since we had been intimate she automatically concluded that we were engaged. I was red hot for her, but this revelation cooled me down considerably. You must understand that I do not breed well in captivity. It wasn’t long after this that I waltzed her over to Jack Kerouac’s dormitory at Columbia University, went upstairs, and brought him down to meet Edie. He fell in love with her on the spot, after which we all sneaked across the street and she put away five hot dogs. That must have impressed Jack considerably because he was in like Flynn, and I found myself out like Stout. My sixty days ashore were up so if I wanted to be drafted I had to ship out on the very next ship hiring in the shipping hall of my union. I went to join a convoy to Liverpool, England, and Edith became ensconced with her new shack-pappy who she subsequently married in jail. [4] This is a long, weary tale that will have to wait for another time. When I returned with the convoy I couldn’t help observing that I had lost my Edith.

To say that I was (excuse the expression) pissed-off was putting it mildly. I didn’t talk to Edith for forty years. When she phoned me at Mother Cabrini Hospital, Edith asked me if I was still pissed-off. I told her I was too old and too tired to be pissed-off. After that conversation my left leg was amputated.

DM: In On the Road, Kerouac describes staying with you in 1947 near San Francisco and working with you as a guard in the barracks nearby. Was this correct? [5]

HC: Most everything Jack wrote was generally true, but he did change the names of his characters, towns, and ships. We never lived or worked in “Mill Valley”, and “Mill City” didn’t exist. Jack and I worked as auxiliary policemen in a shipyard defense housing project nearby Sausalito, across the Bay’s Golden Gate Bridge. Two miles further on was another housing project, called Marin City, where I was living with Dianne. [6] Jack had gravitated from New York to stay with us. Instead of knocking at the door, at 6:30 a.m., Jack climbed in through the ground-floor window of our one-room shack. (This did not become a menage-a-trois).

While Jack was living with me and Dianne in Marin City we went to San Francisco and walked along Market Street. Every dozen blocks he had to stop to renew the newspaper in his shoes, because they both had holes. Dianne didn’t take kindly to stopping in front of street garbage cans so Jack could renew the newspaper. When On the Road was published I wrote Jack and asked him if he was still stuffing his shoes with newspaper. He answered, in a letter, “Yes, I still stuff my shoes with newspaper, but I’ve switched from The Daily News to The New York Times“. In those days The Daily News was a trashy paper and The New York Times gave Jack many fabulously good reviews. (Jack’s publisher had taken an ad covering an entire back page, and costing $5,000.)

DM: In the same book Jack mentions a disastrous dinner with yourself and your “stepfather” at this time.

HC: This was another of the facts that Jack changed in his novel, as I introduced him to my real father in North Beach, California, the Greenwich Village of San Francisco.

DM: In a short story, “Piers of the Homeless Night”, Kerouac wrote about two characters, Matthew Peters and Paul Lyman, from the S.S. Roamer, gunning for you in San Pedro in 1951. How true was this? [7]

HC: This happened, except that the ship was really the S.S. President Harding. “Matthew Peters”‘ real name was Peter Murray, a young Australian con-man whose car I wrecked after he conned me once too many times. “Paul Lyman” was John Holman. I was living at a later date with him and his common-law wife. She seduced me when he shipped out, so I can’t blame him for hating me.

DM: The same story ends with the humorous tale of the pair of you and a piece of tumbleweed … [8]

HC: The huge clump of tumbleweed was unbelievably large, and when Jack and I, both drunk, brought it up the gangway of the President Harding I said something silly to the watchman, like “We are taking this plant to San Francisco for botanical studies”. This was 3 o’clock in the morning when we forced it through the door to the wiper’s foc’sle. When the poor old rummy wiper was asked by the first assistant engineer why he hadn’t turned to at 8 a.m., he replied, “When I woke up I couldn’t get out of bed … someone put a tree in my room!”

DM: And your friendship with Jack continued over the years?

HC: Yes. I visited him several times at his home in Long Island. [9] But after he became a celebrity he could not deal with success and drank cheap whiskey by the quart. It became impossible to stand his company at times, and I gave up on him when he became too difficult to deal with.

NOTES

1. On the Road (Penguin) p. 76.

2. This is the “famous director” father of Remi Boncoeur’s buddy, for whom Sal Paradise writes a “gloomy tale about New York” in On the Road, p. 63.

3. Frankie Edith Kerouac Parker’s “The Popsicle Man”, first published in The Kerouac Connection 6, April 1985, presents Edie’s own story of her early days with Henri Cru and Jack Kerouac.

4. This event is described in Vanity of Duluoz (Penguin) p. 242

5. On the Road, pp. 59-79.

6. Dianne was “Lee Ann” in On the Road.

7. “Piers of the Homeless Night” in Lonesome Traveler. This event is also mentioned in Visions of Cody (Penguin), pp. 107, 114.

8. Lonesome Traveler (Grove), pp. 19-20.

9. Fernanda Pivano’s C’era Una Volta Un Beat (Arcana) pp. 18, 25-26, describes an errand by Henri Cru, on behalf of Jack, visiting Pivano in Milan, Italy, in June 1960, when his ship docked at Genoa. “… My best friend Jack Kerouac … wishes for me to tell you that I am Remi and that he sent me. I have no idea why he wants me to tell you this, but knowing Jack as well as I do he must have some kind of mystical reason.”

[This interview was first published in The Kerouac Connection, 13 (Spring 1987).]