In the spring of 1982 I was working as a deck machinist on a cable-laying ship based out of Norfolk, Virginia. In a copy of the Village Voice that I’d picked up while on shore leave, I saw an advertisement for a writing workshop with Paul Bowles in Tangier, Morocco, scheduled for that summer. I immediately sent away for an application form, and when it arrived, I carefully filled it out and put it in an envelope along with a couple of short stories, the quality of which, according to the enclosed information brochure, would be the determining factor in my being accepted. I gave the envelope to the purser and it went off with the next batch of ship’s mail. My hopes of being accepted were not high. I’d only published a few poems in John Bennett’s Vagabond, written barely a handful of short stories, and didn’t yet think of myself as a real writer. But my ambitions were of the larger-than-life variety.

We sailed out of Norfolk to lay a long stretch of cable in the Atlantic, a job which would take an estimated six weeks. I tried not to dwell on the possible outcome of my application, while working as much overtime as possible, just in case I might actually need a sizable bankroll for a trip to Morocco.

Mainly it was the persona and the character of Paul Bowles that I found so intriguing. For me, he was the American expatriate artist non plus ultra, the bohemian incarnate. Bowles had turned his back on America in a quiet gesture of rebellion in order to follow his true calling as a writer and composer, traveling the world and finally coming to rest in distant, exotic Tangier. The fact that he’d dropped out of college and run away to Paris to rub shoulders with the literati and surrealists, and had managed to be received by Gertrude Stein, was in exact accordance with my nonacademic view of how one could move up in the world. And the fact that it was Gertrude Stein who suggested to Bowles that he stop writing poetry and that he should visit Tangier confirmed my belief in the life-altering power of synchronicity.

Above all, it was Bowles’s unique stance as an outsider in the otherwise clubby world of literature that appealed to me the most. Although frequently associated with the Beats, other than a few snapshots where he appeared in the company of Ginsberg, Burroughs, and Corso, he really didn’t have much in common with the Beats. And despite the fact that Bowles had also experimented with drugs and their relation to creativity, the similarity stopped there. Bowles was too much the dandy and gentleman, traveling across North Africa in his Jaguar sedan with his Moroccan driver and stacks of trunks and suitcases full of impeccable suits and ties and shoes, sometimes even accompanied by a parrot in a cage, about as far from Kerouac’s On the Road as you could possibly get while still being on the road.

Bowles’s own road followed the jagged contours of the perimeters of Western civilization, and he chose to linger in those places where it came into dangerously close contact with native cultures that had little respect or even understanding of Western ways. It was this moveable confrontation between the primitive and the modern that formed the basis of the majority of his work. His macabre and at times nihilistic stories and novels had more in common with postwar existentialism than anything Beat or beatific.

As for myself, I’d originally been bitten by the expatriate writer bug while reading Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. Subsequently I immersed myself in the facts, fictions, and myths of the Lost Generation in Paris in the twenties, as well as the second wave of expatriates that gathered in Paris after the Second World War, and the expatriate community of writers and artists that had lived in Tangier in the fifties and sixties. As a merchant seaman, and between ships on my own, I’d traveled extensively through much of Asia and the Middle East, with the ever-present notion of taking up permanent residence in some foreign, exotic country. But eventually I realized that despite how extensively I might learn the local language or immerse myself in the culture, as a six-foot-two white man in Asia, I would always stick out like the proverbial sore thumb, precluding any real integration or even anonymity.

My first trip to Europe wasn’t until 1981, while working on a freighter that was taking a load of grain from Portland, Oregon, to Lisbon, Portugal. On our arrival in Lisbon, where we spent six weeks while undergoing major repair work on the boilers, I took a room in the old Hotel Bragança, the setting for José Saramago’s masterpiece, The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis. By day I assisted with the repair work in the engine room, and by night I ate frango assado and drank vinho tinto and lingered over gritty black espressos in the very same restaurants and cafés in which Fernando Pessoa had spent time. On weekends I visited the museums, strolled in the parks, or took the train out to Estoril and Cascais. With its old-Europe funkiness and shabby charm, I mistakenly assumed that Lisbon was representative of the rest of Europe, and I was determined to return to Europe with more time, more money, and a portable typewriter. My appetite had been whetted; the question of where I would live out my fantasy life as an expatriate writer was settled.

After our six-week cable-laying stint in the Atlantic, the ship returned to Norfolk, where a letter was waiting for me from the New York School of Visual Arts. I’d been accepted for the workshop, and was expected for the second session, which would take place on the campus of the American School in Tangier in July and August. I was elated, but not without a certain trepidation and uncertainty. Had I really been accepted on the merit of the stories that I had submitted, or were they just accepting anyone who was willing to lay out the money? Could I really expect to learn anything about writing? And how would my work hold up under the scrutiny of Paul Bowles?

I worked for another three months aboard the cable-laying ship and got paid off in Puerto Rico in late June. From there I flew back out to San Francisco to exchange work clothes for street clothes, and then flew to New York, where I stayed for a week prior to catching the flight to Morocco.

The American School was located on the outskirts of Tangier, just over the hill from the American consulate and the apartment building where Bowles lived. The campus itself consisted of a series of nondescript two-story cement buildings sprawled across the hillside, with neatly manicured lawns in between. A high iron fence encircled the campus, complete with hoary old Moroccan watchmen dressed in traditional djellabas at the gates who were on duty day and night.

Participants in the summer program were given the choice of staying in the dormitories on campus, or, if they were willing to spend the extra money, in a nearby hotel. I’d opted for the dormitory and was given a private room on the second floor of the main building, which also housed the cafeteria and lounge. The food in the cafeteria was a colorful and hearty mixture of Moroccan and European food, cooked by a somnolent yet good-natured team of local Moroccan women.

The large window of my room opened to the south and looked out over a sloping hillside laced with winding streets and rows of scattered houses, apartment buildings, small shops, stores, and the occasional vacant lot, where the smoke of small rubbish fires could be seen. The skyline was a jumbled cubist collage of bright white walls and rooftops crowded with spiky TV antennae and rows of colorful laundry flapping in the breeze. The muezzin’s daily calls to prayer, periodically broadcast over PA systems with speakers mounted in the minarets of the mosques, came wavering in through the open window five times a day.

As far as the actual writing workshop was concerned, my expectations were relatively subdued. I’d already taken part in several workshops, and had found them to be of little or no use. In fact, the more workshops I attended, the more it seemed that the chief interest was the creating of a forum for ego-stroking, kudos-gathering, praise-begetting, and hobnobbing with the featured writer (Photograph of me with the author! Autographed copy of his best-selling book!), while the actual craft of writing often played a secondary role at best. Admittedly, the primary motive for my going to Morocco was to meet the legendary Paul Bowles, and if possible, to get to know him. At the time, I had no idea that my visit to Morocco, and my ensuing trip through Europe, would change the course of my life, and that Paul Bowles would have a lasting effect on my career as a writer.

The workshop was co-taught and moderated by Frederic Tuten, an accomplished novelist and short story writer with ample teaching experience, who handled the proceedings with professional and amicable grace. On the first day of the workshop Bowles arrived somewhat later, and prior to that Tuten used the time to explain how the classes would proceed and what we could expect from Bowles. The workshop itself turned out to be more or less as I had anticipated. The various writers read from their precious works, the bulk of which proved to be a lot of surprisingly amateurish, unprofessional, second-rate material. One novel excerpt actually began with the words Once upon a time and went on for many pages until it was suddenly made apparent that the narrator was reading a bedtime story to his daughter, which, as it turned out, had nothing to do with the rest of the novel. I was just getting started as a writer myself; in retrospect, even my own work was far from fully realized. I still couldn’t get over the fact that I’d been accepted on the merits of the work that I had submitted.

It was almost embarrassing to see a writer of such esteem confronted with such paltry offerings. That Paul Bowles managed to formulate any constructive criticism at all attested more to his attributes as a true gentleman than as a writer or teacher. His comments and criticism were concerned primarily with the more technical aspects of grammar and syntax, while rarely did he go any deeper into the motivation of the characters or the actual meaning of any particular story. His manner of critiquing the students’ work was not exactly what I would call perfunctory, but it was definitely limited to the more superficial aspects. I wasn’t disappointed; after my previous experience with workshops, I hadn’t been expecting anything more. I still didn’t subscribe to the theory that you could “teach” writing as such, and I had the feeling that Bowles felt the same way. In fact, in an interview that I read a few years later, which had taken place after Bowles had stopped teaching the workshops, Bowles said explicitly that he didn’t feel that writing could be taught, and that a writer teaches himself by writing—and reading.

Although we had all come (ostensibly) to learn something about writing from Paul Bowles, it turned out that he was able to learn a few things from us as well, at least about the modern world. One woman had not been able to decide on names for the characters in her story, and had simply used XXX, YYY, and ZZZ to identify them, explaining to us in an aside that when she did decide on names, she would go back and change them all with the word processor. As we were pondering this editorial anomaly, Bowles asked in a puzzled tone, “What’s a word processor?” Another student’s story contained a scene that took place in a McDonald’s, with several apparently self-evident references to the food and ambience. When the author had finished reading his piece, Bowles’s only question was, “What’s a McDonald’s?”

During the breaks, as though on cue, everyone was out on the sun-drenched balcony in front of the classroom, edging in for a bit of small talk with Bowles, getting their copies of The Sheltering Sky signed, while having someone take a picture of them together with Bowles.

The writing workshop only took up a couple of hours of each afternoon, which left plenty of free time to lounge around, speculate about potential sexual liaisons with other students, or explore the sleazy, decadent labyrinths of Tangier. There were other classes offered in the morning, and I signed up for a French class in order to polish up my high school French. After my stay in Morocco, I planned on heading off to Madrid and Paris in my ongoing search for the expatriate writer grail. There were other workshops taking place as well, in filmmaking, painting, and photography, so there was no shortage of intriguing after-dinner conversation in the lounge over coffee and Moroccan sweets. There was also an impromptu bar that had been set up in an unused room of one of the school buildings, where students and teachers would mingle while drinking bottles of Stork and Flag beer, often late into the night. When not in the classroom, the students of the writing workshop tended to avoid each other, on and off campus, apparently due to an innate sense of rivalry and competition. My on-campus socializing was primarily with the photography and painting students, who seemed less pretentious and more gregarious and open to experience than the writing students.

For the most part, I spent very little time on the campus. After breakfast in the downstairs dining room, and an hour of rudimentary French, I would usually walk into Tangier, check my mail at the American Express office, buy a copy of the International Herald Tribune, and take up my place at an outside table in front of the Café de Paris. There I would pass the rest of the morning in what I thought to be the tradition of the true expatriate, while warding off the incessant entreaties of the shoeshine boys, lottery ticket sellers, beggars, schemers, and various aspiring con men. As John Hopkins noted in his Tangier Diaries, Tangier is probably the only city with more shoeshine boys than shoes.

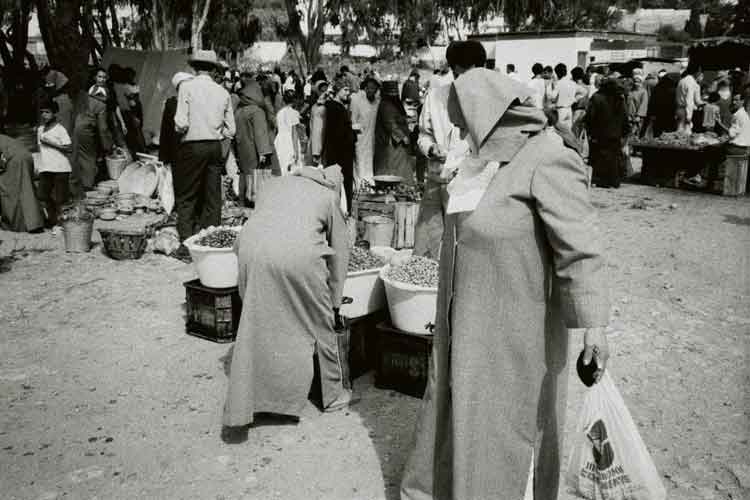

When not drinking mint tea and reading the newspaper in the Café de Paris, or any of the other numerous cafés along the main thoroughfares, I would set off on foot to explore the souks or the medina or any of the various side streets of the warrenlike city. I only would have to take a few steps alone in any direction and I would suddenly find myself surrounded by an ever-growing contingent of would-be “guides,” who were intent on offering their services in return for some form of remuneration. A foreigner unaccompanied by a guide in the streets of Tangier is strictly unheard of, and the persistence of these guides is remarkable. It was virtually impossible to convince them that I didn’t need their services, that I was just looking around, or that I actually knew where I was going (always good for a laugh), and they invariably continued to follow me en masse like a swarm of pesky insects until I finally complied.

I found that the best policy was to decide on one guide in particular, and stick with him for the duration of my stay, meting out small tips each day with one larger payment at the end. This spared me the nerve-wracking hassle of being converged on anew each time I set out on foot in the city. My “guide” was a young kid from the interior named Ahmed, who had come to Tangier to seek his fortune. He’d already worked as an errand boy in a café, as a baker’s helper, as a deckhand on a fishing boat, a laborer on the docks, and just about everything else. It was a typical Moroccan boyhood, right out of A Life Full of Holes. Ahmed’s entrepreneurial know-how and seemingly endless knowledge of the seamy underside of Tangier was truly astonishing. Although Tangier in 1982 was a mere shadow of the proverbial snakepit it once was back in the fifties, with its official status as free port and international zone, it still did its best to live up to its sordid reputation.

In addition to the regular classroom sessions of the workshop, each participant was to have a private conference with Bowles in his apartment, in which the writer’s work would be discussed in detail. My session with Bowles was scheduled near the end of the workshop, and as the weeks went by, I listened with avid interest to the various accounts of the other students’ visits with Bowles. For the most part, the meetings had been curt and businesslike; tea was served, the writer’s work was briefly discussed, a bit of small talk ensued, perhaps followed by more autographs and photographs, and the meeting was over. Many people were apparently disappointed. They hadn’t been offered any kif, they hadn’t been given the key to the citadel of literary success, no famous writers or celebrities were hanging about, and not even Mohammed Mrabet had been there. It was neither wild party nor social visit. It was more like visiting the teacher alone in his office after class.

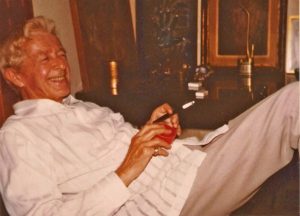

Finally it was my turn for my one-on-one visit with Bowles. I can distinctly remember wondering what was in store for me as I walked over the hill from the campus towards his apartment, which was located across a bleak empty field opposite the American consulate. I climbed the steps to the top floor of the drab, gray apartment building known as the Inmueble Itesa, and knocked on the door. There were footsteps and the sound of the door being opened. There stood Bowles in white slacks and a white turtleneck, the ever-present cigarette holder in his hand, a stack of dusty trunks and suitcases piled against the wall in the hallway behind him.

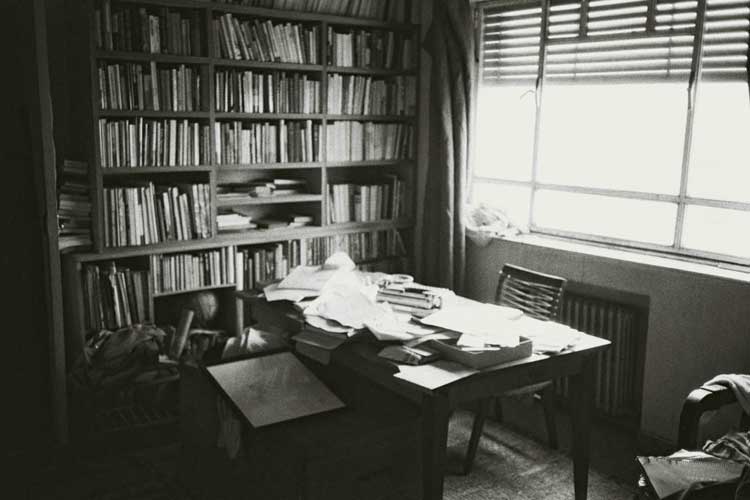

The apartment seemed tiny and dark, illuminated only by the little light that managed to filter in through the plant-infested balcony, which submerged everything in a green-tinted glow like the interior of an aquarium. After walking through the streets of Tangier in the harsh North African sun, it was a welcome change. Bowles was apparently alone. I was offered a seat on a sort of daybed, while Bowles made tea. While we talked, Bowles served the tea in clear glass cups and saucers with wedges of lemon and a bowl of sugar, the sugar remaining untouched by either of us. Bowles took up what appeared to be his regular place in the corner of the room on a stack of cushions on the floor, with one cushion propped against the wood-paneled wall, next to a low table crowded with a small portable radio, a framed painting by Brion Gysin, various books, an ashtray, cigarettes, lighter, and a small metal tin of kif. There were books everywhere, filling the wooden bookcases, stacked on tables, and piled on every available surface.

We discussed the stories I had submitted for the workshop, but for the most part, as Bowles had done in the classroom, he limited his criticism to the more external aspects of the work. He did say that he enjoyed the stories, which did much to boost my morale, and gradually the subject changed to other writers and other writing. It was as though there was an unspoken agreement between us about our view of writing being something that couldn’t be taught. This freed the conversation from any constricting, quasi-academic overtones, allowing it instead to flower into a totally subjective free-for-all that included anything and everything remotely related to writing. Ultimately, I found our discussion much more instructive (and entertaining) than any strict analysis of my work, which I already knew to be flawed and immature.

As Bowles talked, he would roll a filter cigarette back and forth between his fingers, gradually loosening the tobacco, which fell into a small brass tray in his lap. He then scooped the loose kif into the empty tube of the cigarette, packed it down by tapping it on the table, inserted it into his cigarette holder, and began to smoke. All this was done in the same unconscious, habitual manner that an ordinary person would remove a cigarette from a pack and light it. Bowles then asked me matter-of-factly if I would like some kif, to which I said yes, and he passed me the cigarettes and the kif and the brass tray. I followed suit and managed to produce a reasonable facsimile of one of Bowles’s kif cigarettes. Having grown up in California in the fifties and sixties, I was no stranger to cannabis and its byproducts. For me, smoking a joint served the same ice-breaking social function as drinking a round of cocktails. We smoked and talked and smoked some more and the conversation gradually drifted away from writing and literature, and soon we were talking about travel, eventually focusing on Thailand. I had recently been in Thailand myself, and Bowles had spent several months there in 1966 while doing research for a proposed book about Bangkok, which never materialized.

Bowles’s sharp wit, his massive backlog of experience, and his easy, offhand manner made for excellent conversation. We talked more about travel, about Berlin, about Paris, about Gertrude Stein, Virgil Thompson, Aaron Copland, and other luminaries; it seemed that Bowles had a humorous anecdote for almost every subject or occasion. His impersonations of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas were hilarious. I found it hard to believe that I was sitting across from the author of such sinister, macabre, Poe-like works as “The Delicate Prey” and “A Distant Episode,” the two of us laughing like a couple of stoned teenagers. Probably the single most surprising aspect of that first visit was my discovery that Paul Bowles had such a skewed, sparkling sense of humor.

There was the sound of a key in the lock of the front door and someone entering, the curtain in the hallway parted, and there stood Mohammed Mrabet, dressed in a bright blue Adidas track suit and white gym shoes, a black canvas Adidas bag slung over his shoulder. Compact, muscular, and wiry, encircled by an aura of invisible but intense energy and with a sly smile on his face, he immediately reminded me of a Moroccan Bruce Lee. Bowles introduced us and Mrabet sat down next to me on the daybed and immediately went about the business of assembling his kif pipe from the depths of his Adidas bag. He then loaded his pipe with a generous plug of kif and lit it and inhaled and then exhaled in one tremendous blue cloud. I was extremely impressed. At that point I was anyway in a most remarkable state of mind.

In a mixture of broken English, Spanish, and Portuguese, and with the help of Bowles’s spontaneous translations, Mrabet and I were immediately swapping stories of manual labor, working aboard fishing boats, crashing motorcycles, stints in jail, and so on. We were able to bond at a surprisingly fast speed. Mrabet filled his pipe again and passed it to me. He lit the plug of kif and I inhaled until I thought my lungs would burst. I managed to hold it for several seconds before I was seized by a particularly nasty coughing spell. Mrabet laughed, Bowles laughed, and I laughed as well, still coughing, pounding on my chest with my fist, the tears streaming from eyes. To say that the atmosphere had become more relaxed would definitely be an understatement. I felt like I’d been through some sort of initiation ceremony, and in retrospect, I guess I had.

Smoking kif can drastically alter your sense of time, and I’m not sure just how long that first visit actually lasted. Mrabet eventually left. Bowles and I talked some more, and when I noticed that it had become dark outside, I decided it was time to leave. I told Bowles that I was planning to stay on in Tangier for a couple of weeks after the workshop was finished, and he said that I was welcome to visit him whenever I wished, bearing in mind that after five in the afternoon was always the best time.

I walked into Tangier for a nightcap at the Café de Paris, in a combined mood of euphoria and exhilaration. I can remember looking down at the sidewalk, which was made up of a mosaic of uneven, oddly shaped, shiny white stones, and noticing how the long red needles of the trees along the street had fallen to the ground and lodged themselves in the cracks between the stones, creating an endless grid of elaborate, M. C. Escher–like interlocking patterns.

Sitting outside at a table in front of the Café de Paris in the cool evening breeze, drinking a bottle of Stork beer, I mentally recapitulated the scenario in Bowles’s apartment. Had the conversation remained centered strictly around writing, I certainly would have been disappointed. Instead, by dispensing with the teacher-student relationship and fostering an atmosphere of parity and egalitarianism, Bowles had made me feel more like a colleague and fellow writer than a disciple at the feet of the master. This did so much for my self-confidence and determination that I was ready to return immediately to my room and start writing. I couldn’t have imagined a more valuable lesson.

When the workshop finally ended and the other students had departed, I took a room in the nearby Grand Hotel Villa de France, which was perched on the hill above Tangier and the harbor. It was an ancient hotel resplendent with faded glory and spectacular views. Eugène Delacroix, Gertrude Stein, Matisse, and many others had stayed there at one time or another. I visited Bowles daily or every other day, usually arriving at his apartment just shortly after five for afternoon tea. I was always made to feel entirely welcome and never had the feeling that I was disturbing or interrupting anything, even though other guests frequently were there. Although this was still several years before Bowles’s “rediscovery” which followed Bertolucci’s filming of The Sheltering Sky, there was still a constant trickle of visitors, announced and unannounced, who would invariably show up at Bowles’s door hoping for an audience with the reclusive, enigmatic writer. Some of the guests were more welcome than others. Of the welcome variety were people such as Claude Thomas, Bowles’s French translator, a charming woman with whom one could converse for hours on any possible topic. An example of the unwelcome variety were a young hippie couple from San Francisco, decked out from head to foot in traditional Moroccan attire, replete with self-given Moroccan names, who had arrived unannounced, and sat on the floor of Bowles’s apartment enveloped in a cloud of kif smoke. As it turned out, the couple had tape recorders concealed under their clothes, and later attempted to sell their “interviews” to some big-name magazines.

As default master of ceremonies, Bowles had a highly intuitive sense of how to handle his numerous and varied guests. When he sensed that certain people were getting along well with each other, as in the case of Claude Thomas and me, he would frequently leave the room for long spells at a time, under the pretense of searching for some relevant book or article in his study, leaving the two of us to become better acquainted. Or as in the case of the hippie couple from San Francisco, he would simply ignore their presence, talking to me or another guest directly over the shoulders of the somewhat disgruntled couple, as though they weren’t even there.

But there were an equal amount of days where I found Bowles alone or alone with Mrabet, and we would smoke and talk and listen to tapes on his cassette player until well past midnight, when Bowles would have to escort me down in the telephone booth-sized elevator to let me out, the concierge having long since gone to bed. I usually ate before going to visit Bowles, or planned on eating afterwards, so as not to further tax Bowles’s generous hospitality. Sometimes Mrabet came by to prepare Bowles’s dinner, and other times Bowles would prepare something himself in the tiny kitchen next to the living room. We would carry on our conversation while I leaned in the doorway of the kitchen, and he would bring his dinner into the living room on a wooden tray, and eat from the low coffee table while sitting on the floor. There was certainly nothing extravagant or exotic about his meals, which sometimes consisted of nothing other than a warmed-up can of SpaghettiOs, something I never would have imagined finding in Tangier.

Besides writing and literature, I was also interested in music, and was very curious about Bowles’s work as a composer, and especially his recordings of indigenous Moroccan music. This was a subject he talked about with much enthusiasm, constantly jumping up from his cushions, playing and changing tapes like a wizened, white-haired DJ. I had the impression that he felt there had been too much focus on his writing, and that his real passion, music, had been somewhat overlooked. At my request, he made me a cassette of some of the more interesting pieces of Moroccan music that he had originally recorded for the Library of Congress back in 1959, along with a detailed, handwritten list of the exact instrumentation and the locality of each recording. He also made me presents of several hard-bound, first editions of his books and translations, some of them translated into German, as well as a copy of the Black Sparrow edition of his wife’s collected letters, edited by Millicent Dillon.

One evening when the two of us were sitting around smoking and talking about music, Bowles had put on a cassette and was in his study looking for a book about Virgil Thompson that he wanted to show me. As usual, I’d smoked a lot of kif, and the music that was now coming out of the cassette player was sounding most strange indeed; so strange that when Bowles came back into the room, I asked him if there was something wrong with his tape player. Bowles laughed, his blue eyes twinkling mischievously, and he assured me that there was nothing wrong with the machine. What we were hearing was Conlon Nancarrow’s Studies for Player Piano.

We passed almost each and every evening in an elliptical, at times bounding, discussion that encompassed a vast landscape of art, literature, music, and creativity in general. Each time I left the Inmueble Itesa, I had the feeling that my consciousness had been expanded to altogether new parameters. The mental picture of Bowles that I’d brought with me to Morocco of the aloof, opaque, sphinxlike writer rapidly evolved into something altogether different. Bowles was humorous, congenial, generous, witty, warm, and downright menschlich. Hell, he even ate SpaghettiOs.

When my extended two-week stay came to a close and I was preparing to depart by ferry for Spain and my planned journey through Europe, I couldn’t resist the impulse to buy my own copy of The Sheltering Sky at the Libraire des Colonnes in Tangier, so that Bowles could sign it on my last visit. In it, he wrote For Mark Terrill, at one stopping-place in his odyssey. All best, Paul Bowles, Tangier, 13/VIII/82. I thanked Bowles for his hospitality and told him I would probably return again next summer. He gave me his mailing address, saying to give him a few weeks’ notice prior to my arrival, and wished me luck with my travels.

I left Tangier on the ferry to Algeciras with the feeling of having achieved much more than I had originally expected. I hadn’t learned much about writing in a technical sense, but I’d learned an immense amount about what it means to be a writer. And I’d gotten to know Paul Bowles, as much as anyone can really “know” someone as oblique and reticent as Bowles.

From Algeciras I set off on a three-month trip through Europe, and when my money began to run low, I flew back to San Francisco and shipped out again, returning to Europe in the fall of ’83. This time I was staying in Germany with Uta, a woman I’d met by chance on a train platform in Hamburg the year before, and, together with some friends of hers, we drove down to Spain in an old Opel Blitz police van. When the fall semester at the university in Hamburg was about to begin, Uta caught a train back to Hamburg and I stayed on in Tarifa, Spain. From there I took the hydrofoil across the straits to Tangier.

I’d written Bowles from Hamburg, telling him of my plans, and he was as welcoming and hospitable as ever. Summer being over, the visitors were few and far between. I remember the first day I came over for tea and found Bowles listening to a tape of the Police. Bowles was always listening to strange, obscure music, from George Antheil to Conlon Nancarrow to indigenous African music, but the Police seemed particularly incongruous and out of context. I mentioned this to Bowles, and he said someone had sent him the tape because of the song “Tea in the Sahara.”

The pattern was the same as the previous year; I would stop by the Inmueble Itesa either daily or every other day at five for tea, and invariably would stay late into the night, smoking kif, listening to music, and talking about writing, music, and travel. Mrabet came by just about every day, which meant more smoking, more laughing, and more storytelling. Sometimes Mrabet would lapse into a totally improvisational story, which Bowles would simultaneously translate for my benefit. I stayed in Tangier for a week, again at the Hotel Villa de France, and then returned to Tarifa to drive back to Hamburg with my friends. From Hamburg I flew back to San Francisco, shipped out again, and returned to Germany and Uta in January of ’84, this time with the intention of staying.

I got a job as a welder in a shipyard in Flensburg, and began working on a novel, unsure if writing novels was what I really wanted to do, but determined to give it a try. In September Uta and I got married and I quit my job in Flensburg and moved back to Hamburg. I finished the novel, and in September of ’85, I took the train down through France and Spain and caught the ferry from Algeciras to Tangier. The Hotel Villa de France had become too expensive for my meager budget, so I found a cheaper room in the Hotel Lutetia, just down the street from the Café de Paris, only to find out later that Bowles had lived in that very same hotel many years before. My room was on the top floor, with a wide balcony and an incredible view of the entire harbor. Originally built in 1935, the hotel had definitely seen its better days, and the furnishings and decor all appeared to be original, including the mattress on my bed.

I’d brought the novel with me and I gave it to Bowles, unsure if he would actually read it or if we would even get to discuss it. But Bowles said that he had time, and that he would read it. When I visited Bowles the next day, he said that he’d read my novel the night before in its entirety and had enjoyed it immensely. He said he frequently received first novels from aspiring writers, but rarely were they any good. He also said that certain images and scenes in my novel had made indelible impressions on him. But we both agreed that there was a problem with the way I’d chosen to portray the psychological metamorphosis of the main character at a key point in the narrative. Rather than make any concrete suggestions as to how I could resolve the problem, Bowles simply left the issue open, which, in retrospect, was the best thing he could have done.

This time I stayed for over a month, and besides the usual evening visits, we made several day trips in Bowles’s bronze-colored ’67 Ford Mustang with his driver, Abdelouahaid, to Cape Spartel, the Caves of Hercules, and other locations in the vicinity of Tangier, usually returning in the afternoon to pick up his mail from the post office and do some shopping before returning to his apartment. During one trip to the coast near Cape Spartel, we’d parked the car and were wandering around in the rocks above the beach, admiring the incredibly clear view of Spain looming across the straits. This trip I’d brought my camera along, and had been taking many pictures. At one point I looked over and saw Bowles down on his knees amidst some boulders, gently probing a hole in the rocky ground with a long blade of grass. I asked him what he was doing, and he told me that this was the way Moroccans caught scorpions. He suddenly yanked out the blade of grass, the other end of which was now in the clutches of a large, black beetle. Bowles got to his feet and stood there with the beetle crawling over his hands, saying, “Well, it’s not a scorpion …” He still had his sunglasses on, now with a slight smile on his face, and he suddenly appeared to me more like a mischievous kid than a septuagenarian writer and composer. I was so caught up in the ambiguity of the image that I forgot to take a picture.

Evenings at the Inmueble Itesa were spent in the usual way: listening to the news on BBC, smoking, talking, listening to music, and interacting with whoever happened to stop by. I was always amazed at Bowles’s seemingly limitless hospitality and patience, no matter who might come knocking at his door.

One evening near the end of my stay, while the two of us were alone and discussing writing, Bowles went into his study and returned with a sheaf of papers, which he then gave me. It was the galley proofs for an unpublished story he’d recently written, entitled “Massachusetts 1932.” He said I could take it with me back to the hotel, read it at my leisure, and return it when I was finished. I remember walking back to the hotel that night, stoned as always, wondering what I had done to be worthy of such an honor. As soon as I got back to the hotel, I sat down and read the story through in one sitting. It was a long monologue written entirely without any punctuation whatsoever, mimicking perfectly the drawling, disjointed nonstop speech of the main character of the story, an old farmer who is hoping to sell his farmhouse to a young couple from the city. With Bowles’s typical subtlety, it gradually becomes apparent during the course of the narrative that the farmer’s two previous wives had both committed suicide in the house.

I was mesmerized by the story. Each and every word fit together like an intricate puzzle, the flow of the narrative being entirely dependent on the use of the language and the order of the words. There were a few articles and prepositions such as the and if that had been inadvertently transposed by the typesetter, and Bowles had made his corrections with a red pen, just as he had done on our manuscripts in the workshop. It was thus possible to see just how crucial the word order and syntax actually were. I’d never read anything like it; and the chance to see the story in an unfinished state was like having a magician show you how he did his best tricks. A popular myth in circulation at that time was that Bowles had stopped writing after the death of his wife, Jane, in 1973. Not only was this entirely a myth, but here was proof that Bowles, at seventy-five, was still pushing the envelope of the accepted norms of narrative writing. Apparently, even for Bowles, the learning process was far from complete.

Several years were to pass before I returned to Tangier again, although Bowles and I did correspond in the interim. Occasionally I would send him a short story I’d written, and he would respond with his commentary and criticism. When I finally returned in the summer of ’89, this time with my wife, Uta, and with my second novel, the scene at the Inmueble Itesa had changed drastically. Bertolucci had acquired the rights to The Sheltering Sky, and filming was about to begin. The trickle of visitors, most of them unannounced, had become a constant stream. Nonetheless, Bowles made us feel entirely welcome, and always seemed to find time for us. He somehow even managed to read my novel, which we ended up discussing over the heads of a living room full of visitors, ranging from some Italian rucksack tourists hoping to get their books signed to a French film crew hoping to film an interview. Amidst all this, Bowles told me that he thought that the novel was excellent, and that he saw no reason why I shouldn’t be able to get it published. When I mentioned that this was easier said than done, he proposed to personally write a letter to City Lights Books, recommending my novel for publication. It was a weird moment, sitting there in Bowles’s apartment, full of people vying for his attention, fully aware that I was teetering on the brink of what might be the big breakthrough I’d been dreaming of. I thanked Bowles for his generous offer, but politely declined, saying that if I were to become truly successful, I’d rather have done it on my own, without any direct intervention. I caught a glimpse of that knowing twinkle in Bowles’s eyes, and I knew that I’d made the right decision. He did give me the address of Robert Sharrard, then associate editor at City Lights, which I jotted down in my notebook as a possible contact for later use. Bowles had taken me as far as he could; the rest was up to me.

Fortunately, there were other days when Uta and I visited Bowles and found him alone, or with Mrabet. While drinking tea and talking, there would invariably be a knocking at the door, and Bowles would jump up and run into the bathroom, saying to Mrabet over his shoulder, “Whoever it is, I’m not here!” Mrabet would answer the door, which we couldn’t see because of the curtain in the hallway, and we could hear him telling whoever it was that Bowles wasn’t there, and that he didn’t know when he would be back.

My wife had an excellent opportunity to experience Bowles’s endearing naïveté when the two of them were discussing various means of modern-day travel. She had explained to Bowles that we were traveling with just our rucksacks, with tents, sleeping bags, and a gas stove, primarily staying at campgrounds, with the occasional hotel in between. “Ah!” Bowles exclaimed, “I always wondered what it was that all those young people were carrying around on their backs.”

Bowles got up from his cushions and took the book from the pile and kneeled down at the coffee table in front of us and painstakingly pointed out a long list of errors that he had marked in the text, as well as several photographs with erroneous captions, which he had crossed out and replaced with the correct information in his own handwriting. The book was obviously the source of much ire for Bowles, and he made no secret of his dismay and disappointment.

This made me wonder why he had the left the book out for everyone to see.

This was a side of Bowles I had not previously experienced, another idiosyncratic aspect of Bowles’s character; the simultaneous vying for both anonymity and recognition. It reflected a curious mixture of British understatement and a childish striving for approval. For the most part modest and unassuming, Bowles apparently enjoyed letting it slip out that, for example, when the Rolling Stones had recently visited him, Mick Jagger had sat on that very cushion over there by the fireplace. It was the same with the biography. The fact that the book was so obviously flawed and totally unauthorized gave Bowles the chance to play down the fact that a major, comprehensive biography had been written about him—no small token of veneration in a life and artistic career otherwise plagued by obscurity and neglect.

When my wife and I left Tangier that summer in 1989, I had no way of knowing that it would be the last time I would see Bowles. We corresponded intermittently over the years but eventually even that contact broke off, as Bowles became inundated with more correspondence than he could keep track of. During his last years, Bowles was afflicted with eye trouble that precluded any writing or composing whatsoever.

When Bowles died on November 18th, 1999, I found myself looking back on our initial encounter and the subsequent visits, curious to reassess the total impact that he’d made on me. As I had anticipated from the very outset, I didn’t learn “how” to write from Bowles, but what I did learn from him was seminal in terms of my own development, not only as a writer but also as a person. It may be possible to teach the technical aspects of writing, but this is not what Bowles was about. Bowles helped me find my own way, opened the doors, and gave me the necessary nudge in the right direction. His encouragement, which always came in an indirect, roundabout fashion, did more for my self-esteem and confidence than any degree, diploma, award, or prize could have possibly done. But above all, it was his commitment to his artistic vision and being true to himself that made me seek Bowles out as both role model and mentor. Following his inner voice at the risk of total obscurity, Bowles personified the sort of creative integrity that seems essential in becoming a true artist. This proved to be the most valuable lesson I ever could have learned.

Here to Learn: Remembering Paul Bowles was first published as a limited edition chapbook by Green Bean Press in 2002. It has since sold out and is no longer in print.

Here to Learn: Remembering Paul Bowles was first published as a limited edition chapbook by Green Bean Press in 2002. It has since sold out and is no longer in print.

It was reprinted in Gargoyle 59 in 2013.

This is its first appearance online.

Teresa Conboy says

This was excellent! Thank you Mark Terrill for sharing this story on Empty Mirror. I was fortunate to be able to check out from a local library the rereleased field recordings that Bowles made all those years ago, and as well picked up a used copy of his autobiography (that I now know will not tell much, after reading your story, which probably told a lot more). Thanks again – really enjoyed reading this.