“I have nothing to offer but my own confusion.” — JK

It is intriguing that secular, educated Americans often have difficulty with the rituals and story of Christianity, seeing it as irrational, but eagerly read their horoscope or find new age morality or belief systems relevant to their lives. As traditional organized religion has lessened in influence, spiritual needs and explanations persist. People have substituted one “irrational” set of beliefs for another. Buddhism, for many, finds a way around this problem. For some practitioners, Buddhism doesn’t rely on magic or even a deity of any kind. It is a system of metaphysical laws of cause and effect. For sure, it is a spiritual system, but it can be understood as logical and orderly. For this reason, it is the perfect fit for the post-religious rationalist who requires a spiritual component to their lives. This is one among many ironies of the role that American writer Jack Kerouac played in spreading the popularity of Buddhism, for he lived his life as an irrationalist; a wandering poet, a mendicant Catholic and at times a reactionary alcoholic.

It should be noted, however, that for most of Kerouac’s readers the irrational is what they craved. For serious students of Buddhism, Kerouac is a beginning not an end. He is America’s Hermann Hesse; the German author of Siddhartha, his novel of the life of the Buddha from 1922, would also become a counterculture favorite and fixture of high school syllabi in the 1970s. Finding the transcendent and authentic is a strident theme in Beat Generation literature and especially the works of Jack Kerouac. This is what his frequently young readers craved, a way out of their humdrum suburban lives of parents, teachers, rules, and church.

Previous generations of Americans didn’t have the time to question the assumptions of society. They were too busy trying to make ends meet, often in families of eight or ten children. Baby boomer parents struggled through the Great Depression and then had to fight in World War Two. But their children were part of the first generally affluent society in American history. Kerouac himself was a child of the depression, born in the same year that Hesse’s novel was released. The baby boom generation is considered by most demographers to include those children born between 1945 and 1965.

Early boomers would have been able to read Kerouac’s most famous and enduring book, On the Road, as adolescents when it was issued in 1957. But it was the children of the 1960s who really embraced Kerouac as one of their key prophets. His influence was keenly felt, especially in music. Bob Dylan and the founding members of The Doors and The Grateful Dead have all cited Kerouac as an indispensable inspiration. What would become the counterculture and hippie movement were the progeny of the Beat Generation. It might be said that Kerouac’s influence on American cultural life was greatest in music and in the evolving outlook and orientation of young people which included spiritual pursuits, environmentalism, peace activism and alternative lifestyles, not in changing the direction of literature. Although Kerouac certainly wasn’t interested in telling anyone else how to live, his novels of his social worlds ended up doing just that. Who wants a job in Squaresville, USA when you could get your kicks traveling around, drinking wine, smoking tea, reading poetry and making love?

Understanding Kerouac’s appeal to young people can be appreciated, even if the impact of the writer and his books seems somewhat out of proportion. But Buddhism is another thing altogether. Real Buddhism requires discipline of just the kind that Kerouac’s readership was uninterested in. Kerouac’s Buddhism might be called the “gateway drug” to the real thing. The Kerouac mystique was carved out by On the Road. This book enamored a large number of America’s youth and has proven to be inspirational up to the present. This novel was followed by The Dharma Bums which explicitly took up Buddhism as the path to “it”, the transcendent realms expressed as the ultimate goal of the peregrinations described in On the Road.

The Buddhism discussed in The Dharma Bums is of the sort of dabbling you might expect from a ragtag group of bohemians. The novel describes orgies, drinking bouts and a kind of half-baked mountain climbing expedition. The “bum” part of the novel’s title should tell the reader of its orientation. There is, however, more to this story than the hijinks of artistically inclined young men. The novel’s protagonist is famously based on the serious scholar, Zen Buddhist, translator and poet Gary Snyder as Japhy Ryder. Snyder has been at pains to point out that he is in reality quite a bit different from the character portrayed in the book. Nevertheless, the Buddhism described by Kerouac showed that the real work of religion and art can live cheek by jowl with what might be described as “screwing around” and that these things are indeed intertwined and perhaps necessary to each other.

These ideas again, as in On the Road, are appealing to adolescents and young people who naturally wish to have fun and adventures. Hedonism and spirituality are portrayed as part of the same aim of transcendence. For many readers, The Dharma Bums describes and appealing and tolerant religious and lifestyle alternative to the standard American Protestant work ethic. For the “dabblers” in Buddhism, this was enough. For those with a serious interest in this venerable religion, it was the first step in a long road of learning and practice. The Dharma Bums was published in 1958. Nine years later came the Summer of Love in San Francisco, the city that is a key setting in Kerouac’s novel, and the apogee of the intertwining of spirituality and self-indulgence.

American Buddhism and the Beats

The “Zen boom” of the 1950s is considered a major watershed in American Buddhism’s history and lineage (Seager, 1999). However, the story of American Buddhism began far earlier. Asian immigrant communities formed the first Buddhist presence in the United States in the 19th century. These communities were largely insular and did not transmit their beliefs to the host population. However, some artists were pursuing an interest in eastern religions at this time. In the pre-Civil War period the so-called Transcendentalists, a group of writers led by Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Walt Whitman were enamored of eastern mysticism and took an interest in Buddhism. The Beat Generation is known to have drawn inspiration from the Transcendentalists, especially Whitman. The Transcendentalists, like their Beat counterparts, were not doctrinaire Buddhists, and though they had texts in translation they had no Buddhist teachers. They relied on a romantic vision and their own creativity and in this sense were very similar to Kerouac’s highly individualistic Buddhism. Turning from their transcendental predecessors the Beats articulated a mystical impulse to drop out from the moral restraints of modern society. This foundational altruism emerges intuitively and responds directly to problems resulting from the mechanization of daily life that limit knowledge and potential to dictums of impersonal science and rational fact (Shipley, 2013). The Beat Buddhism of Kerouac is open, creative and generous. The reader is invited to take part in the visions and insights of the author. The Transcendentalists, Beats, and a range of other writers are responsible for helping to indigenize the dharma through literary means (Seager, 1999).

It was not until immigrant teachers came to America that any kind of true Buddhist communities could be established. This was a process that began in the early 20th century. In the main, Japanese masters came to teach enthusiastic American seekers of enlightenment. This meant that Zen Buddhism was the first school to take root in the United States. This is also the school of Buddhism which was most associated with the Beat Generation. These teachers included Shaku Soyen, Sokei-an, Nyogen Senzaki, and D. T. Suzuki who was very influential in California Buddhism and who the Beats personally met with. Ruth Fuller, who would sponsor Gary Snyder’s studies in Japan, was an important female pioneer of American Buddhism who studied under and later married Sokei-an. Thus connections in American Buddhism were forming, primarily in New York and San Francisco.

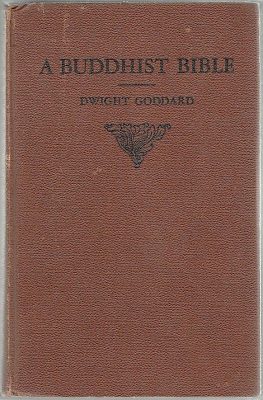

An important development in American Buddhism was the publication of Dwight Goddard’s The Buddhist Bible in 1932. Kerouac discovered this book in 1954 which became a catalyst for his work on Buddhist themes. Kerouac’s fascination was with Buddhist religious experience, to be obtained through meditation and a particular Buddhist lifestyle, that of an itinerant wandering mendicant, was inspired by this initial encounter with Goddard (Johnston, 2013).

Goddard’s book was an anthology of Theravada and Mahayana texts emphasizing sutras. Sutras were to become Kerouac’s primary connection to Buddhist wisdom. Buddhism attracted Kerouac because it seemed to make sense of the central facts of his experience and to affirm his intuition that life was dreamlike and illusory (Prothero, 1991). Goddard’s work also brought important Buddhist principles to the growing number of Americans interested in not just Buddhism but a broad range of alternative spiritual and humanistic movements. D.T. Suzuki’s lectures at Columbia University in the mid-1950s gathered the attention of artists, writers, and the media. A connection was made between Suzuki’s ideas and the principles of psychology, especially psychotherapy (Seager,1999). The human potential movement and Buddhism were conflated. An American style of Buddhism was forming which was political, social and artistic in nature.

In the 1950s the ideas of Alan Watts, an English Episcopalian priest and Buddhist scholar who had settled in the San Francisco Bay Area, were a major force in introducing Buddhism to the masses through his radio broadcasts and lectures. It can be said that D.T. Suzuki, Watts, and the Beats together created the Zen boom of the 1950s. Though Suzuki and Watts were scholarly and careful in their approach, the Beats were carefree and individualistic. Kerouac in particular presented Buddhist practice in The Dharma Bums as based upon a rather Blakean notion that excess leads to wisdom. The Beats forged a link between enlightenment and drug use that would be picked up by the hippies.

Though the Beat Generation was highly differentiated and unconventional, their religious vision animated their everyday lives and their art (Lardas, 2001). In this sense, they were serious in their pursuit of enlightenment. Of the Beat Generation writers, Phillip Whalen, Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg would become genuine Buddhists. Snyder is perhaps the most serious, as he became a Zen monk in Japan for several years. These three men and many others from the initial 1950s Buddhist movements forged an American Buddhism that is still with us today. From a small and fringe spiritual movement, Buddhism in its various forms is now an established minority religion with millions of adherents. The American convert community comprises its majority.

Kerouac was especially interested in suffering and its causes, which is an important aspect of Buddhist teaching. Kerouac’s mental health was a personal worry which led to his study of the dharma, but in his books there is a strong element of concern for others. There is a warmth in the voice of the author, a friendliness, and commiseration. Kerouac’s Buddhism, like his Christianity, was primarily concerned with alleviating suffering and with kindness.

Baby boomers

As stated above baby boomers were the first generally affluent generation in American history. This comes with some caveats. Baby boomers here denotes middle-class white Americans, mostly Christian and some Jewish. Black Americans in the postwar years were still largely disenfranchised. Many whites still lived in poverty, especially in rural areas of the American south. The United States was a far whiter country in the postwar years than it is currently and generally, whites were well-off. So why were the children of affluence so likely to rebel against a world that had given them so much?

There were a number of social, cultural and historical factors that made this the case. The cultural forms of the 1950s and early 1960s in America can be viewed in hindsight as artificial and escapist. The parents of boomers who knew all too well how difficult and even horrifying life could be through experience of poverty and war, valued safety and security which made them, generally speaking, conservative. But this conservatism was played out against the background of an emerging liberalism. Progressive government initiatives like the GI bill allowed American veterans quality, largely free, higher education after World War II. In California, especially, the university system was greatly expanded and made affordable. Infrastructure throughout the country was massively improved. Schools, hospitals, roads and public works were constructed. Postwar affluence was spread throughout society at the macro and individual level. In short, the postwar generation believed in the government’s ability to do good. This was liberal Republicanism of the sort personified in President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

However, a culture of Perry Como and Disneyland was not speaking to the youth of the postwar baby boom. There was a lack of connection to the “real” and “authentic” in the arts. The culturally astute found the genuine in the jazz and blues music of black Americans. The Beat Generation expressly championed jazz. Kerouac with On the Road discusses jazz at length as an expression not just of the authentic but as a porthole to the transcendent.

The baby boom generation that reached adulthood in the 1960s made this a crucial time for religion in the United States (Sherkat, 1998). The threat of nuclear annihilation seemed to confirm the apocalyptic vision of early Beat Generation writing about the decline of western civilization (Lardas, 2001). Events began to chip away at the postwar vision of religion and society. The assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 left people not only shocked but many deeply suspicious. But it was the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights movement that politically crystallized the baby boomers in opposition to the dominant society. The Establishment was seen by these young people as hypocritical and senselessly destructive. The postwar revival in Christian religion with its celebration of the “American way of life” ended in the 1960s when the nation entered a period of self-doubt (Hutchison, Albanese, Stackhouse & McKinney, 1991).

Sexuality was another aspect of society worth questioning. The mores of the depression era generation were out of step with the wants and needs of baby boomers. The first oral contraceptive, the “pill”, was introduced in 1960, allowing women to have sex freely without the stigma of pregnancy out of wedlock. The sexual codes of earlier decades, reinforced by religious dogma, were largely untenable to the baby boomers. The search for a more permissive worldview left the door open for a new spirituality.

Freeing themselves from the shackles of long-held dogmas, boomers were potentially at sea in their spiritual lives. Sunday school morality and consumerism were increasingly at odds with the ideals of the baby boom. Boomers, who had grown up in material comfort, didn’t want more stuff. Nor did they wish to be told what to do by religious systems represented by their parents. The Orient has lived in the imagination of westerners as a place of exoticism and hermetic knowledge (Said,1979). Eastern mysticism gelled with baby boomer consciousness which said, a la Kerouac, that somewhere out there was “it” the holy grail of transcendence, wisdom, and peace of mind. Christianity, especially as practiced by parents and the dominant society was not viewed as a fruitful method in this search.

On the Road openly discusses drug use, especially smoking marijuana in the Mexico section of the book. The notion of visions and sudden illumination is also a common theme throughout Kerouac’s oeuvre. Recreational drug use was rare in the late 1950s when both On the Road and The Dharma Bums was released. Again Kerouac was prescient in these discussions, which seemed to be nudging society generally and young people in particular in the direction of accepting drugs as both a means to have fun and to expand their consciousness and spiritual gifts. As we know, drug use was a big part of the counterculture ethos.

The Beat Generation is acknowledged as a precursor to the hippies and as foundational to the counterculture. This counterculture was in fairly short order absorbed into American and eventually world culture. What was avant-garde in the late 1950’s became decidedly co-opted and mainstream by the 1970s. The counterculture’s allegiance to an anti-commercial image, however manufactured, would prove to be one of its most marketable commodities (Zimmerman, 2006). Such is the power of the American media and culture behemoth that nothing can overthrow its innate power to fetishize and commercialize art and ideas for the sake of making money. This fact was not lost on Kerouac and contributed to his unraveling. For a few years, from the mid to late 1950’s, Kerouac was serious Buddhist, practicing meditation and writing several works on Buddhist themes, some which were only published posthumously. This was a legacy which would leave a lasting mark on American religious life and one that, had he lived to see its fruition, he could have been proud of. As it was Kerouac died bitter, drunk and miserable, convinced he had been misunderstood and exploited (Berrigan, 1968). But for baby boomers, Kerouac was their prophet; of sex, drugs, freedom and bhikkhu wisdom.

The Dharma Bums

Kerouac’s novel is dedicated to Han Shan, the legendary poet and Buddhist holy man of the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Little to nothing is known of the real Han Shan, a name which translates from Chinese as Cold Mountain (Snyder, 2013). It is said that Han Shan lived outside and wrote his poetry on cave walls, only to be later written down by others. At this stage in his Buddhist studies, Kerouac considered himself like Han Shan, a bodhisattva and a wandering poet turning the wheel of the dharma with acts of kindness. The hijinks which make up a good portion of the action in The Dharma Bums masks a serious effort on the part of its author to rescue himself from the malaise of alcohol abuse, depression, and anxiety.

Kerouac took to Gary Snyder as his muse, as he had with Neal Cassady in On the Road. Kerouac, jaded and troubled, saw Snyder, shiny and new (8 years his junior), idealistic, talented and spiritual as a positive force worth emulating. Snyder (1930) is happily still with us. Kerouac has been dead for 48 years. This says something about the differences between the two men and they were significantly different types of people. Whereas Kerouac burned out, Snyder burned bright, with the steady flame of his deep commitment to Zen Buddhism, his academic work, and poetry. The Dharma Bums is very revealing of how those in the Beat Generation who sought transcendence primarily through intoxication foundered on the rocks of mental illness, substance addiction and an early demise. Kerouac drinks heavily throughout the novel and though Snyder as Japhy Ryder could be said to appreciate the bacchanalia which is a primary theme of the book, his work is always foremost in his orientation to life. Kerouac lacked this self-discipline, despite his very real dedication to his art. His alcoholism is quite evident in The Dharma Bums.

The action described in The Dharma Bums covers roughly late 1955 through early 1956. It includes the famous Six Gallery poetry reading in San Francisco which has gone down in history as an important moment in the development of the California poetry scene known as the West Coast Renaissance and of the Beat Generation in general. Allen Ginsberg read “Howl” for the first time in public at the Six Gallery recital which took place in October 1955. “Howl” is considered the plaintive cry of the Beat Generation and its most clear iteration in a single piece of art. Ginsberg’s opening lines are famed:

“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night…”

The poem became the subject of a celebrated obscenity trial involving its publisher City Lights and its owner Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the great Beat literary figure and poet. Ginsberg’s poem became an anthem of the counterculture and frankly discussed taboo subjects like homosexuality and drug abuse. The poem is decidedly Whitmanesque, panoramic, ecumenical and universalist. These are all themes that resonate with Kerouac, who was never strictly speaking a Buddhist but saw in Buddhism and other traditions commonalities of thought and action with his own Catholicism based upon kindness and compassion.

The Buddhism of The Dharma Bums had a lasting effect on American civilization. Because Kerouac’s novels primarily appealed to younger readerships, the first introduction to millions of Americans and others around the world to Buddhism is in this novel. The back to nature themes of The Dharma Bums were also seized upon in the counterculture as part of a spiritual lifestyle, along with consuming LSD, which by the late 1960s, Allen Ginsberg was actively advocating (Zimmerman, 2006).

Loosely speaking, the kind of Buddhism practiced in The Dharma Bums is Zen, which emphasizes meditation (zazen), understanding the true essence of reality and the Buddha nature. This knowledge is put into everyday practice in the service of others. Kerouac was not a doctrinaire or systematic man and his “Zen Buddhism”, though practiced with enthusiasm, was an example of syncretism, suffused with Catholicism and the author’s unique perspectives as an artist. This was “Beat Buddhism” of the kind that was roundly criticized by the likes of Alan Watts. But not all experts found the Beats irrelevant in their spiritual quests. Even an exacting scholar like the Zen master D.T Suzuki recognized that these young American writers had something to say. He noted prophetically: “The ‘Beat generation’ is not a mere passing phenomenon to be lightly put aside as insignificant. I am inclined to think it is somehow prognostic of something coming, at least, to American life” (Pearlman, 2012). But he also noted after meeting Kerouac and Ginsburg that Kerouac’s biggest flaw was that he “misunderstood the essence of freedom”, which is that we are already free and that it is the human mind that thinks we are not free. Suzuki felt that:

“They are struggling, still rather superficially against democracy, bourgeois conformity, economic respectability, conventional middle-class consciousness, and other cognate virtues and vices of mediocrity.” (Pearlman, 2012).

Suzuki felt that the Beats and Kerouac in particular were “rootless” and thus floundering in their quest for new and authentic ways of living. The reader can sense in The Dharma Bums Kerouac and his friends feeling and improvising their way through life without a clear program or goal. The reliance on the “kicks” of On the Road is still there. Drinking and sex are still major themes of this book. Their ethos, if it can be defined as such, is summed up by a euphoric Japhy Ryder (Gary Snyder):

“See the whole thing is a world full of rucksack wanderers, Dharma Bums refusing to subscribe to the general demand that they consume production and therefore have to work for the privilege of consuming, all that crap they didn’t really want anyway such as refrigerators, TV sets, cars, and general junk you finally always see a week later in the garbage anyway, all of them imprisoned in a system of work, produce, consume, work, produce, consume, I see a vision of a great rucksack revolution thousands or even millions of young Americans wandering around with rucksacks, going up to mountains to pray, making children laugh and old men glad, making young girls happy and old girls happier, all of ’em Zen Lunatics who go about writing poems that happen to appear in their heads for no reason and also by being kind and also by strange unexpected acts keep giving visions of eternal freedom to everybody and to all living creatures.” (Kerouac, DB, pg.73).

This is an apt description of the hippie movement in which millions of young Americans dropped out of conventional modes of being in society and pursued lifestyles centered on communal living, music, drugs and sex. The Dharma Bums can be seen as a bridge between the bohemian 1950s and the counterculture of the 1960s. The hippies rebelled against what had been traditionally considered work/life practices in the United States. Kerouac’s style of Buddhism fed into the notion that the American work ethic was in some measure a slave ethic meant to tie people onto the treadmill of work for the sake of consumption instead of fulfillment. The real work of The Dharma Bums, “dharma” means work as well as truth from the Sanskrit, was creative, personal and spiritual. It was about finding meaningful potentials in individuals. These ideas were very appealing to the well-to-do youth of the 1960s who knew, having grown up in material comfort, that accumulating things wouldn’t make them happy but experiences, especially sensual experiences, and personal development could. Many brands of Christianity as practiced in America frown upon sensual experience, even as sex is used in the US both to titillate in ubiquitous pornographies and to sell things. Buddhism provided a more balanced and healthy approach to sex than this schizophrenia. This was an important point in favor of the kind of Buddhism practiced in The Dharma Bums which combined sensuality and spirituality, not the asceticism of some spiritual approaches. As Japhy tells Ray, “I distrust any kind of Buddhism or any kinda of philosophy or social system that puts down sex” and that sexual freedom is “what I have always liked about Oriental religion.”

Kerouac’s prescient ethnography of American Buddhism

As a writer, Kerouac was at the forefront of social changes in America life. This happened largely as a result of his work chronicling his social group which in turn became his novels produced as roman a’ clef. On the Road, for example, can be read on different levels and is frequently appreciated for its putative political qualities or as a novel of “resistance”. A close reading of this novel reveals its most essential quality, that of an ethnographic portrait of mid 20th century America and an emergent literary scene of great importance (Amundsen, 2015). Likewise, The Dharma Bums is an ethnography of the nascent Buddhist scene in northern California.

Gary Snyder, Phillip Whalen, Allen Ginsberg and others less well known all are featured in The Dharma Bums and all would become leading figures in American Buddhism, especially in the San Francisco Bay Area. Kerouac, through chronicling the lives of his friends, created meaningful ethnographies of subcultures that would in time become countercultures and in short order part of mainstream American civilization. It is worth considering that Kerouac always kept a journal with him in which he wrote thickly descriptive notes of places, landscapes and people very analogous to an ethnographer’s field notes. These were the building blocks of his novels. Kerouac was noted as a genius of “spontaneous prose” in which he would write in a torrent of words, often working for many hours without stopping. But this creative burst was only the final step in the long process of participant observation and note taking. That Kerouac chose to write about his friends and their interests is auspicious for readers who wish to learn about American civilization. This is so because his friends became extremely important people in American cultural life. When he began writing On the Road, he could not have known that would be the case. This is the sign of a Kerouac gift which has been largely ignored, his perspicacious and almost unconscious understanding and depiction of trends in society. He seemed to know that his work was of serious importance and was a vectoring force in American life, oftentimes without liking very much where it was all headed. This tapping into zeitgeist is perhaps Kerouac’s real genius, rather than his prose, which in hindsight seems rather ordinary compared to earlier innovators in the novel like Joyce and Faulkner.

But Kerouac was the perfect exemplar of the Beat Generation. He was handsome and had been a genuine hobo. He was romantic in the public imagination. These qualities were not lost on his publishers and the press, who wanted a public face for the Beat Generation. Kerouac, who for so long found literary success elusive, had at last been recognized not only by youthful hipsters but by the establishment in the form of the New York Times, whose Gilbert Millstein wrote a glowing review of On the Road in 1957. This single review changed Kerouac’s life forever. He was an instant celebrity and was immediately attached in the public’s perception with the Beat Generation as its leading exponent and philosopher. The media began playing up seedy caricatures of “beatniks” in turtleneck sweaters spouting poetry, orgies, violence, and youth run amok. This was, of course, absurd. When On the Road was published Kerouac was a 35-year-old man, somewhat world-weary and a serious artist who had been writing since he was an adolescent. Suddenly he was thrust into the spotlight as the “voice of a generation” and spokesman for a group which was largely the creation of the media and the marketing spin of Allen Ginsberg. Kerouac, quiet and shy when not drinking, wanted nothing to do with any of this. He just wanted to practice his vocation as a writer.

Herein lies the problem that defined the remainder of Kerouac’s life. When The Dharma Bums was published in 1958 he was experiencing all of the problems of fame with few of the benefits. He was not financially secure as the deal for On the Road with his publisher Viking paid him a mere $5000.00 advance, a very low sum compared with far less successful books at the time (Kerouac, 1999). His career was grossly mismanaged and he was encouraged to rush books into print to capitalize on the fame of On the Road. His editors at Viking didn’t understand his work or his artistic goals. He was constantly harangued to do publicity events which he abhorred and which he couldn’t accomplish sober. All of these factors made the peace he found in Buddhist practice more relevant than ever and this the very time where his Buddhist phase ended. The author retreated to the Catholicism of his childhood, living with his mother variously in New York and Florida while drinking heavily all the time.

Nevertheless, the seeds planted with The Dharma Bums would grow to fruition. Kerouac had introduced millions of young people to Buddhism when the religion was a marginal footnote in America’s religious landscape. He also instilled the notion that San Francisco was the epicenter of all that was hip, spiritual and fun.

Conclusion

It has been said “Comes the hour, comes the man.” Jack Kerouac was just the man to introduce Buddhism to the masses in the United States. Though he was far from the first to write about the subject and Buddhist studies in America go back to the 19th century Kerouac, at the historical juncture of the 1950s and 1960s, was the weight on the scale, the tipping point, that brought great numbers of young people in the United States and beyond to appreciate the possibility of transcendence through Buddhism.

But this meant Kerouac’s brand of Buddhism. Because Kerouac was famed for On the Road, his most famed novel, The Dharma Bums, which followed, must be read in light of the earlier publication. On the Road presented a vision of restless young people traveling around America rather aimlessly pursuing transcendence. This was found only briefly here and there for the author and his friends, usually through intoxication or drug use. Kerouac was also at pains in this book to present the commonplace, both in people and places as divine. For Kerouac, the everyman and even the bum was somehow part of the holy order of a spiritualized America seen through the eyes of the author. Sex was the “one and only holy thing” for the novel’s hero Dean Moriarty (Neal Cassady). There are spiritual yearnings in On the Road, but that is where they mostly stay, in the realm of longing and the briefly glimpsed.

All of this vague ennui struck the young people that read the book so avidly, and still does, because this is exactly how many young people feel. They want to live, but they are not exactly sure how to go about it. They wish to transcend the mundane and find things that are beautiful and meaningful which is a challenge for all people in life. Kerouac was nice enough to come up with the answer to the problems presented in On the Road in The Dharma Bums. The answer was Buddhism, but luckily with a lot of the fun from the previous book. This wasn’t Christianity’s “Though shall not…” with the attendant guilt but Beat Buddhism’s “Though shall…and like it.” Sex, drinking, drugs, naked dancing, mountaineering, adventures of all kinds were possible and it was all spiritual and OK.

The link to the hippie ethos is obvious. Armies of young people descended upon San Francisco in the summer of 1967 with just such a mindset. Very few of them would have been Buddhists, but many would have read Kerouac and most would have considered themselves “spiritual”. The ideas in The Dharma Bums, even for those who hadn’t read it, was the worldview of these young people.

By the time of the Summer of Love, Kerouac was jaded and nearly dead. He was a chronic alcoholic and more bitter than enlightened. Kerouac was a man troubled by ultimate questions. The search for answers animated his literary and personal life. Though the subject of the Beat Generation’s art is the ground of numinous presence rather than the ground of urban materiality (Arthur, 2012), Kerouac found in the road, in its grit, adventure and cultural forms, the needed pathway of transcendence. His acolytes followed him and found Buddhism along the way.

One of the fine qualities of The Dharma Bums is of its evocation of a time and place. Kerouac beautifully sketches characters and scenes which stick with the reader. He had an uncanny ability to draw upon his social world to create lasting literature and was able chronicle in his book the nascent Buddhist scene in his circle of friends which went on to become an important milestone in America’s religious history.

Alas, Kerouac fell away from Buddhism and its precepts. In the end, another credo from The Dharma Bums would prove a fitting epitaph, “I don’t know. I don’t care. And it doesn’t make any difference.” Kerouac might be amused to find out that Dharma Bums is now the name of a yoga pants company. Or he might see it as just another example of a civilization that he ever so briefly and yet also deeply changed.

References

Amburn, E. 1999. Subterranean Kerouac: The Hidden Life of Jack Kerouac. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Amundsen, M. 2015. On the Road: Jack Kerouac’s epic autoethnography. Suomen Antropologi: Journal of the Finnish Anthropological Society 40(3): 31-44.

Arthur, J. (2012). “The Chinatown and the City: Kingston, Kerouac and the Bohemian Bay Area.” Modern Fiction Studies, 58 (3), 239-259.

Berrigan, T. 1968. Jack Kerouac. The Art of Fiction. The Paris Review, 43.

Ginsberg, A. 2001. Howl and other Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Publishers.

Hutchison, W. Albanese, C. Stackhouse, M. & McKinney, W. 1991. The Decline of Mainline Religion in American Culture. Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation,1 (2) pp. 131-153.

Johnston, P.J. 2013. Dharma Bums: The Beat Generation and the Making of Countercultural Pilgrimage. Buddhist-Christian Studies, 33, pp. 165-179.

Kerouac, J. 1957. On the Road. New York: Viking.

Kerouac, J. 1991 [1958]. The Dharma Bums. London: Penguin.

Kerouac, J. 1999. Selected Letters. Anne Charters (ed.). New York: Penguin.

Kerouac, J. 2007. The Portable Jack Kerouac. Anne Charters (ed.). New York: Penguin Classics.

Lardas, J. 2001. The Bop Apocalypse: The Religious Visions of Kerouac, Ginsberg and Burroughs. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Pearlman, E. 2012. Nothing and Everything – The Influence of Buddhism on the American Avant Garde: 1942 – 1962. Berkley: North Atlantic Books.

Prothero, S. 1991. On the Holy Road: The Beat Movement as Spiritual Protest. The Harvard Theological Review, 84, (2) pp. 205-222.

Said, E. 1979. Orientalism. New York: Vintage.

Seager, R. 2000. Buddhism in America. New York: Columbia University Press.

Sherkat, D. 2001. Tracking the Restructuring of American Religion: Religious Affiliation and Patterns of Religious Mobility, 1973-1998. Social Forces, 79 (4) pp. 1459-1493

Shipley, M. 2013. Hippies and the Mystic Way: Dropping Out, Unitive Experiences, and Communal Utopianism. Utopian Studies. 24(2) pp. 232-263.

Snyder, G. 2013. Cold Mountain Poems. San Francisco: Counterpoint.

Zimmerman, N. 2006. Consuming Nature: The Grateful Dead’s Performance of an Anti-Commercial Counterculture. American Music, 24 (2), pp. 194-216.

Leave a Reply