William Burroughs was troubled in his childhood by a “fear of nightmares.” The dreams themselves weren’t always so bad. Like when he seemed to wake to find little men playing in a block house he’d made – uncanny yes, but it filled him with wonder rather than fear. It wasn’t what he saw so much as what he didn’t see. “I was afraid to be alone, and afraid of the dark, and afraid to go to sleep because of dreams where a supernatural horror seemed always on the point of taking shape. I was afraid some day the dream would still be there when I woke up.”

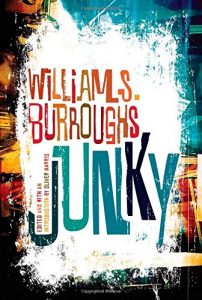

It was the expectation of nightmares, more than the dreams themselves, that troubled him. And the expectation that something worse was to come, when the nightmare would become a reality, filling the waking world with the horrors of the dark. Junky is the story of how his reality in fact came to be filled with such horrors: through the development of his drug addiction.

Although Burroughs does show drug addiction to be something horrifying and dehumanising, he doesn’t portray his addiction in an entirely negative light. “I have never regretted my experience with drugs,” he writes. “I think I am in better health now as a result of using junk at intervals than I would be if I had never been an addict. When you stop growing you start dying. An addict never stops growing.”

And in this constant growing and shrinking – habit, kick the habit, start the habit again – junk teaches the user lessons about life. “I have learned the cellular stoicism that junk teaches the user. I have seen a cell full of sick junkies silent and immobile in separate misery. They knew the pointlessness of complaining or moving. They knew that basically no one can help anyone else. There is no key, no secret someone else has that he can give you.”

When you start on junk, you don’t know what you’re messing with. Until you’re addicted you don’t know what addiction is, and until you’ve kicked you don’t know what withdrawal is. And once you do know these things it’s too late. “You don’t wake up one morning and decide to be a drug addict. It takes at least three months’ shooting twice a day to get any habit at all. And you don’t really know what junk sickness is until you have had several habits.” You’re entering a new mode of existence with junk. There will be suffering, degradation, and a high risk of death. An alternate and terrifying world. And Burroughs makes this plain. It is amazing that so many people felt, still feel, that Burroughs was somehow glorifying drug culture.

Burroughs describes the first time he used junk. Instantly there was horror and nausea: “I had the feeling that some horrible image was just beyond the field of vision, moving, as I turned my head, so that I never quite saw it.” The childhood nightmare returns: a horror without definite shape. Balanced with a relaxing, euphoric feeling, “a spreading wave of relaxation slackening the muscles away from the bones so that you seem to float without outlines, like lying in warm salt water.” But I wonder, when he would go on to use the drug again and again, was he chasing the euphoria only? Or was there some unconscious desire to find again that childhood nightmare? A morbid desire to revisit that primal horror?

And that original nightmare stayed in the mind of Burroughs so that he could commit it to the page. And not just in this negative description of the lurking nightmare as something indeterminate and hidden. We find a bit further on in Junky descriptions of prophetic and archetypal horrors that would appear again and again in his later work: “One afternoon, I closed my eyes and saw New York in ruins. Huge centipedes and scorpions crawled in and out of empty bars and cafeterias and drug stores on Forty-second street. Weeds were growing up through cracks and holes in the pavement.”

Burroughs is describing a vision he had as a symptom of withdrawal from junk. Is he describing the first time he was visited by the centipedes and scorpions? Or were these in his childhood dreams too?

But it’s the spectral, indescribable element of horror that’s really important in Burroughs. Just as the tentacles in H.P. Lovecraft are only a small part of the overarching ongoing story of a primordial horror beyond human imagining, so the scorpions and centipedes in Burroughs are symbols of a greater, sublimely paranoid picture of a world controlled by forces we can never understand. And it’s this obscure vision, of a world controlled by evil minds with malevolent powers, that he first caught a glimpse of in his childhood nightmares.

Vincent Zangrillo says

I must’ve missed that part in Junky when Bill talks about nobody being able to help, no one having the secret, or maybe I was too young and inexperienced to realize it’s the cold, hard truth about heroin withdrawal (even more true when you are kicking in jail), the coldest hardest truth that I have ever heard. So true it hurts to even read it, nevermind go through it. A truth so true, so hard, so cold, that you can’t really understand it unless you’ve been in that cell.

Sam Silva says

great essay