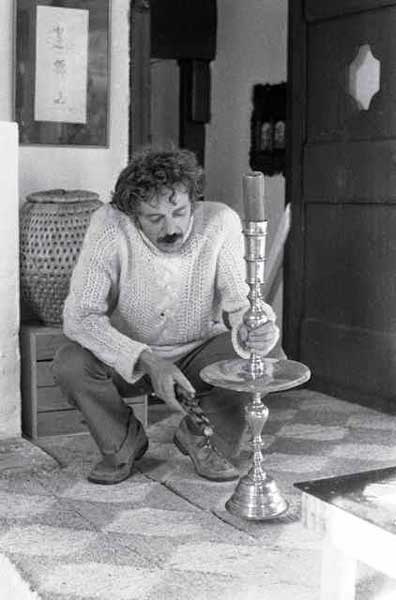

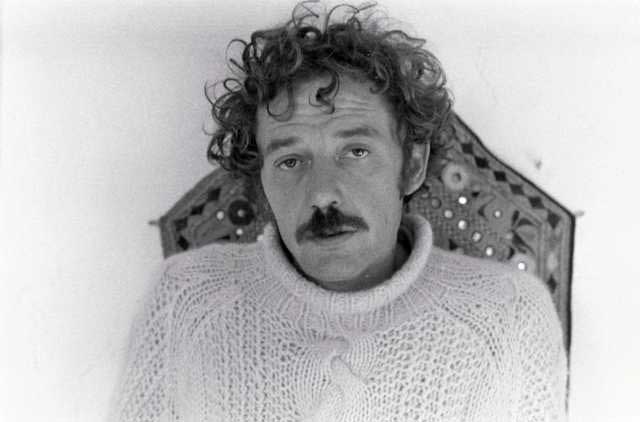

Sinclair Beiles was a South African writer associated with the Beat movement of the late 50s and early 60s. During the time of his earliest successes, he moved from South Africa to Paris, to live with the community of writers and artists, which included Gregory Corso, Brion Gysin, and William Burroughs, among others, at what would become known as The Beat Hotel. Yet, this “beat” tag could not contain him. He also spent the early 60s in Greece, working with the Greek artist Takis on multimedia works, all the while spooling out his own brand of surrealistic, enigmatic poetry. He floated around Europe in the decades that followed… coming back to his homeland in the 90s, settling down in the artists’ enclave of Yeoville, in Johannesburg. He continued to experiment restlessly, until his death in 2000. He is relatively unknown outside of Beat and South African literary circles. Hopefully this article will go a long way towards correcting that.

Gerard Bellaart is a legendary small-press publisher in France and was Sinclair Beiles’s publisher in the 1970s, with his Cold Turkey Press. I asked him how Beiles should be remembered. He replies that Beiles work is “of the calibre of Celan”, the famed French surrealist poet, but doubts that his reputation will rise anytime soon. “Beiles’ oeuvre as a whole has been neglected (read: ignored),” says Bellaart. He says that:

Literary market forces thought it more profitable to hail Burroughs and Gysin as the founding fathers of the ‘cut-up’. Neither had either the culture or background to recognise the principle of cut-up inherent, say in Mallarmé’s “Coup de Dés”, and in Baudelaire’s essay on de Quincy’s definition of Palimpsest for that matter. Sinclair Beiles of course knew these works by heart and in French.

Furthermore, he believes that Beiles was an originator, and should be recognized as such. He continues:

It was Sinclair Beiles who first developed the technique of using a layer of text as a transparent entity, the superimposition of which would create an entirely new and unpredictable context. The further appropriations of the technique by Burroughs and Gysin we do not need go into at this point.

But perhaps the leading authorities on Beiles and his work are Gary Cummiskey and Eva Kowalska, editors and publishers of Dye Hard Press in South Africa. They published the definitive reference on Beiles, Who Was Sinclair Beiles?, the updated version of which was published earlier this year.

Gary Cummiskey agrees. “Beiles was an outsider,” he says. “If one regards Beiles as Beat poet, then his work is also quite different from many of the US Beat poets. Even if the quality of his writing is uneven at times – and it is very uneven – that does not mean that his work should be ignored and deemed unworthy of serious consideration.”

Beiles often found his mental faculties unravelling, and spent time in psychiatric care, on and off throughout his life. According to Cummiskey, “In the introduction to Sacred Fix, Beiles said that most of the works contained in the volume were written while under psychiatric care in London…” but at the same time, “he could sometimes get quite angry when he found references to his being in psychiatric care. He once maintained he had never been mentally ill, but had simply gone into care on occasions for purposes of relaxation.” Kowalska and Cummiskey both agree that “his poetry reflects aspects of his mental illness,” and Cummiskey in particular contends that Beiles “always felt he was writing against time, before the next breakdown occurred, perhaps before the final collapse.”

Cummiskey states that “one of the reasons we compiled the book came from the realisation that while many people know of Beiles, or at the very least know his name, few know of or have even read his work.” He believes that Beiles should be more than a footnote in the Beat story or the saga of William Burroughs.

He does admit that when he first met Beiles, he was “eager to hear about Burroughs, and Ginsberg, as no doubt did just about every other wide-eyed visitor who pitched up at his door.” But he also says that “afterwards I wondered if he ever got annoyed at this, you know, people contacting him to find out about the others, and not so much about him.”

Beiles’s biographers say that he considered himself a writer for the world, not beholden to any country or literary community. They say he “distanced himself, geographically and ideologically, from South Africa and its poetic culture. Kowalska says “Beiles was idiosyncratic and tended towards the antagonistic, on both a personal and political level…”

Cummiskey says that “Beiles spent almost three decades out of South Africa, coming back only occasionally, and finally returning to settle down only in the late 1970s/early 1980s.” He continues by saying that:

…apart from his first titles, the majority of his collections were published in limited editions by small and sometimes short-lived presses…His selected poems, A South African Abroad, was published by Lapis Press in California in 1991, but even then a relatively small number of copies found their way to South Africa. Also, as Eva says, Beiles did not want to fit in, he did not want to be part of the South African literary scene. He wanted to distance himself from it, but at the same time he was also quite angry at being ignored.

Cummiskey, along with many other critics of Beiles’s work, agrees that “it didn’t seem to matter whether what he was producing was good or bad, so long as he kept writing. Hence the very uneven quality of his work.” He goes on. “The ‘first thought, best thought’ thing of the Beats is… not to be taken literally.” The work of Beiles’s contemporaries such as Corso, Kerouac, and Ginsberg “was carefully crafted…” as were the works of his surrealist predecessors Andre Breton and Paul Eluard. He doesn’t damn Beiles for his uneven work, and recognizes that Beiles is far from unique in this regard. He gives the example of the Russian poet Mayakovsky, whose “complete works total 12 volumes, half of which are now dismissed even by his admirers as doggerel and propagandist hack work, though Mayakovsky himself had a high opinion of it.”

Barry Miles, the legendary Beat biographer (and author of The Beat Hotel) believes that these twin Achilles heels, of poor distribution of the work and spotty self-selection skills, doomed Sinclair Beiles to the literary ghetto in which he currently lives.

When I spoke to Miles for this article, he shed a little light on the collaborative relationship and friendship between Beiles and his better-known comrade, Bill Burroughs. He says that “Burroughs first knew [Beiles] in Tangier, though not well. He always thought that Sinclair was crazy, but many poets are, or have had episodes of craziness. I recently catalogued Burroughs’s archive for the last twenty years of his life and there were more than seventy letters from Sinclair there so they remained in touch until Burroughs’ death.” He draws a distinct line between the purpose of Burroughs’s cut-ups and Beiles’s. He says that “Burroughs was looking for a new angle on the original subject, whereas Sinclair was looking for an overall density of words – quite difficult stuff usually. His poems, if you can call them that, are heavy going and don’t really make much sense to me though others clearly think they do.”

Miles believes that the main reason Beiles’s work stayed relatively underground was that “he never published enough – there was no proper book, just very small limited editions. (not counting his pornography for the Olympia Press, but that was under a pseudonym).” Miles says that “had City Lights or one of the other well-known publishers done a book of his work” he might have enjoyed a greater readership during his lifetime.

Still, many decades later, the work endures, with limited distribution and all of the rest of the problems a writing life brings. Beiles felt fame was a double-edged sword, Cummiskey says. He also said that some critics have accused Beiles of exploiting the fame of his more well-known writer friends, for his own gain. Cummiskey goes on to say that for himself, “the answer lies not so much in Beiles the personality but in his work. It is a matter of whether his work is of value, of whether he made a contribution to South African literature.”

References:

Bellaart, Gerard. Email correspondence with author.

Miles, Barry. Email correspondence with author.

van Eeden, Janet. “Editors Gary Cummiskey and Eva Kowalska in conversation with Janet van Eeden.” kagablog.

Cummiskey, Gary, and Kowalska, Eva, editors. Who Was Sinclair Beiles? Revised and Expanded Edition Dye Hard Press, 2015.

Jan C. DUVEKOT says

During the sixties Sinclair stayed several times at our place, near the Sarphatipark in Amsterdam. We had mutual friends in Paris at the Hotel Stella, in rue Monsieur le Prince. A famous hangout during the Vietnam troubles. We worked on texts for the Paris Review. Sinclair needed a stunning quantity of drugs to keep going. The psychiatrist in Amsterdam wondered how he could function. We found Sinclair functioned just fine: he disregarded his surroundings, did not get into small talk and wrote wonderful poetry that replaced superflouous conversation. He was a good lover, I was told by his girlfriend. He behaved like an off stage jazz musician, which I found had a very coherend and poetic spaciousness. Pity he didn’t talk more during our rides in town. He did occasionally talk about Africa but then promptly fell asleep in my 2CV. I remember him once reading a long poem about jazz musicians in imaginary London in the 14th century. His poetry books in our appartment were stolen. Good sign. Cold Turkey Press in Rottterdam deserves credit for saving much poetry from oblivion.

Josh Medsker says

Hi Jan! I’m just reading this now! Sorry for the extremely tardy comment. Wow! What a great remembrance you wrote. Thank you! –Josh

Bruce says

Enjoyed the article on Sinclair Beiles, great to see him getting some acknowledgment.

Josh Medsker says

Hi Bruce! Thank you for the kind comment! I’m sorry for being so effin’ tardy with my comment! Take care!– Josh