Bob Kaufman, known in France as the American Rimbaud, was one of the original Beat poets to come out of the Fifties. He is rightfully regarded as one of the most influential black poets of his era, but his poetry transcends any race identification. In San Francisco’s North Beach, home of the West Coast Beats, he was regarded as the original be-bop poet. As a jazz poet, he was second to none.

In the Fifties Kaufman co-edited Beatitude Magazine with fellow poet William Margolis, while reading his work with the likes of Allen Ginsberg, Michael McClure, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Diane Di Prima, and other noted poets of his day.

In North Beach, in a six-block area from lower Grant Avenue to upper Grant Avenue, there existed a large number of bars, cafes, and coffee houses, frequented by poets, artists, and jazz musicians. While Grant Avenue was the center stage of creativity, the bevy of coffee houses and bars extended from Broadway and Columbus, all the way to the produce district, where the self-proclaimed King of the Beats, Eric Big Daddy Nord held court in a large warehouse on the fringe of the old produce district. Kaufman and his wife Eileen were frequent visitors to Eric’s pad, joining in on the festive activities.

Kaufman seldom talked about his childhood and upbringing in his native New Orleans, but we know from Eileen Kaufman that he was the youngest of thirteen children, born on April 18, 1925, the son of a German Orthodox Jew and a Black woman from Martinique. His grandmother came to the U.S. on a slave ship from the gold coast of Africa, and he was proud of his African roots. As a child, his mother saw to it that he regularly attended Catholic mass, but he would also join his father in the synagogue on the Sabbath, while at the same time learning about the voodoo beliefs of his grandmother. Kaufman’s religious upbringing was nothing less than a spiritual mosaic, although in later life he would mock God in several of his poems.

Kaufman was arguably the most intelligent of all the Beat poets and writers, including Ginsberg. He boarded a ship at a young age, and for twenty years sailed with the U.S. Merchant Marines, traveling around the world several times. It was during one of these trips to Greenland that he suffered frostbite, causing him to lose 40% of his hearing.

Kaufman’s literary education began at sea when a first mate gave him books of the masters to read, among them the works of Jack London. His formal education was obtained at an elementary school in New Orleans, and, he later attended the New School of Social Research in New York City. It was while spending time in New York that Kaufman met Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs, but it wasn’t until later, in Big Sur, California that he met Jack Kerouac and Neil Cassady.

In May 1958 Kaufman met a young woman named Eileen, and a short time later they were married. In 1959 City Lights published a Kaufman broadside, Abomunist Manifesto, and shortly thereafter a second broadside, Second April, was published.

A year later City Lights published a third Kaufman broadside, Does the Secret Mind Whisper. These early broadsides earned Kaufman a cult following in San Francisco’s North Beach District.

In early 1959 Ron Rice directed a film titled The Flower Thief, which was shot in San Francisco, starring the North Beach bohemians, with Kaufman playing a leading role. The film was later shown in Italy, where it received critical acclaim.

In late 1959, and into the early part of 1960, Kenneth Tynan produced a film titled Dissent in the Arts in America. Kaufman appeared in the film, which was never shown in the U.S., after Tynan was called to appear before the infamous House Un-American Activities Committee. It was, however, shown in Europe, which partly accounts for Kaufman’s popularity abroad. During the early Sixties he read his poetry at the Gaslight and other popular coffee houses in New York’s Greenwich Village, but returned to San Francisco in 1963.

On a November afternoon in 1963, Kaufman watched on television the assassination of President Kennedy. Many of Kaufman’s friends have said after watching the assassination that Kaufman took a Buddhist vow of silence, which lasted nearly twelve years, until the end of the Vietnam War. This is only partly true, for Kaufman did occasionally speak with friends, even if it was only to say hello or to bum a cigarette.

Kaufman was not a prolific writer, but his poetry books are generally regarded as among the best verse written by any of the Beat poets. His first book, Solitudes Crowded With Loneliness, was published in 1965 by New Directions, and caused an immediate stir in local literary circles. The book consisted mainly of early poems written while he traveled from New York to San Francisco and back again. It would later be published in France, in 1975, and helped him gain a larger foreign audience. Kaufman’s second book, The Golden Sardine, was published in 1967 by City Lights, which earned him a solid reputation in the U.S., England, and France.

By the late Fifties, Ginsberg, Corso, and the rest of the Beat gang had left North Beach, leaving behind Lawrence Ferlinghetti to tend City Lights Book Store. Other than Ferlinghetti, Kaufman was the last of the recognized original gang of Beats too regularly make the rounds of North Beach.

Kaufman would not see another book of his in print until 1981 when New Directions published Ancient Rain, which consisted of previously published poems alongside unpublished poems written between l973-l978.

In October 1982 Kaufman emerged from near obscurity to read one of his poems on the PBS television show Images, and from that time on rarely read his work at local literary events.

Jack Micheline, a Beat poet friend of Kaufman, said in an interview I did with him in the eighties that he considered Kaufman to be an original jazz poet, a poet deeply steeped in the jazz tradition. His work is essentially improvisational, and was at its best when he read with various jazz musicians.

His poetic technique resembles that of the surreal school of poets, ranging from a powerful, lyrical vision to the more prophetic tone that can be found in many of his political poems.

Golden Sardine contains a striking political poem on the death of Caryl Chessman, a convicted kidnapper, robber, and accused rapist, who many even to this day feel was wrongly sentenced to death for crimes (kidnap and rape) for which he was innocent. The tone of the poem is one of anger against a system intent on destroying the mind and body. Kaufman’s defiance parallels Chessman’s own defiance, evidenced by Chessman refusing to admit his guilt, and be spared from the gas chamber.

Carl (sic) Chessman knows the Governor of

California knows. Good Johnny the Pope

Knows, Salvatore Agron knows & all the

Leaky eyed poets know. In their poems

No one is guilty of any thing at any time

Anywhere in any place

The difference between Kaufman’s anger and the anger expressed by other Beat poets is that he could move from anger to humor in a matter of seconds. But even within the humor we find a biting message of condemnation of what the poet considered a system speaking of honor and God on the one hand while practicing rape and plunder on the other.

Death is a familiar subject in many of his poems. His obsession, perhaps awe, with death is evident in such early poems as Results of A Lie Detector Test, which appeared in the Golden Sardine.

From the sleeping calendar I have stolen a

month

I am afraid to look at it. I don’t want to know

its name

Clenched in my fist I feel its frost. Its icy

face.

I cannot face the bewildered summer with a

pocketful of snow

I imagine the accusing finger of children

who will never be born

How to shut out the cries of the suffering

Death wishers, awaiting

The silent doors of winter tombs, deprived of

cherished exits.

I shall never again steal a month…or a week

or a day or an hour

Or a minute, or a second, unless I become

desperate again.

You won’t find any pretension in Kaufman’s poems. There is no attempt at word play. The poems fall naturally without a hint of strain to them. His early poems still ring true today, even after two-plus decades have passed.

Kaufman also spoke of a driving force of love. Many of his poems speak of dreams and the imagery the mind produces, as if the poet realizes it is the dream that keeps the artist going, and keeps at bay the imperfections and pain.

But Kaufman saw clearly through the dream, as evidenced in a stanza from another poem from The Golden Sardine, “The Mind For All Its Reasoning.”

The mind for all its complicated reasoning

Is dependent on the whim of the eyelid

The most nonchalant of human partsOpening and closing at random

Spending its hours in mystique

Filled with memories of glimpses

& blinks.

His work is particularly harsh toward the church. In Early Loves, he closes his poem with “Tears will wash away her dirty murdered soul/God will be called upon to atone for his sins.”

To have had the privilege of reading Kaufman’s work, or to have shared a drink with him, or to have read with him, or spent time with him in his small North beach hotel room, with little or no conversation taking place, was an experience not easily forgotten.

Kaufman considered himself a Buddhist, and believed that a poet had a call to a higher order, and like the Buddhist’s, he accepted a vow of poverty and a non-materialistic life. He wasn’t like many of the Beat poets who frequented the beach, in that he never attempted to push his own literary career. He was an oral poet, who didn’t write for publication, or fame and fortune, unlike so many of our would be poets writing today.

When I returned home from the military in 1958 North Beach was where it was happening. It was poetry, music, and the spoken word. Jazz was central to what was happening. Wes Montgomery and Cal Tjader were very much part of the scene. The Fillmore District, a largely black community, was known as Bop City, a hangout for musicians like Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan, and other jazz notables. It was common to see New York jazz musicians visiting San Francisco’s Fillmore District, and it was here that musicians and lovers of jazz gathered in the early hours of the morning, and poets like Kaufman fed off the vibrations.

While Ginsberg was reading his poetry to appreciative audiences, Kaufman chose another path, becoming the undisputed street poet, who frequented the Co-Existence Bagel Shop, located on the corner of Grant and Green, writing and reciting his poetry there. He also liked to frequent Aquatic Park during the early morning hours, after the bars had closed down. I frequently saw him in the company of two black male friends; Kaufman and one of the other two scribbling their thoughts down on paper, while the third member played the conga drums, passing around a bottle of red wine, or lighting up a stick of weed. They would still be there when I left for home in the wee hours of the morning.

It wasn’t that poets had not been in the area long before the Beat poets arrived. It was just that for the most part they were largely invisible, while the jazz scene, on the other hand, flourished. Then along came Lenny Bruce, whose comedy routine, at the time, was considered outrageous and obscene. Bruce, no doubt, inspired others to come out and say what was on their minds, even if it meant being arrested, as Bruce frequently was. Not that Bruce didn’t encourage the police, seemingly taking delight in baiting them, waiting for the right moment to drop the word cocksucker on them, which would bring a quick close to the show. In this, he and Kaufman had something in common, when it came to taunting the police.

Kaufman’s nights at the Co-Existence Bagel Shop are the stuff legends are made of. North Beach regulars remember Kaufman for his frequent bouts with police officer William Bigarani, which took place at the Bagel Shop. Bigarani had a vendetta for Kaufman, and having gone to high school with Bigarani, I know there was more than a little racism behind his harassment of Kaufman. It had to gall him to witness Kaufman in the company of white women. Never one to back down from a confrontation, it didn’t take long for Kaufman to become a marked man, and he frequently found himself hauled downtown to the old Hall of Justice, where he was introduced to a cop’s alter ego, the nightstick.

To be fair to the San Francisco Police, they were generally permissive in their attitude toward the Beats, at least up until the time tourists and college student thrill seekers began taking over the neighborhood. The truth is that Kaufman often encouraged the wrath of the police, goading them onto a predictable confrontation. He considered the Bagel Shop his private domain and reigned over it like a king.

I frequently hung out at the Bagel Shop and can vividly recall Kaufman entering the establishment, climbing up on top of one of the tables, and reciting a newly written poem. Indeed some people hung out at the Coexistence Bagel Shop in the hope of seeing him come in and read his work. When he read, there was near silence. The people hung on his every word. But his fate was sealed the day he wrote on the walls of the Coexistence Bagel Shop, “Adolph Hitler, growing tired of fooling around with Eve Braun, and burning Jews, moved to San Francisco and became a cop”. This was the beginning of Kaufman regularly being hauled down to City Prison, to spend the night, before facing a stern faced judge in the morning.

In 1978 Kaufman abruptly renounced writing and again withdrew into solitude, not emerging again until l982, to read one of his poems on the PBS television show Images. From l980 up until the time of his death, he would occasionally read his poems in public, but by then he had been reduced to a ghost of his former self, walking the streets of North Beach; twitching, blinking, mostly an un-speaking victim of a failing liver, and a brain diminished by drugs and forced shock treatments undergone at Bellevue Hospital.

The last five years of his life saw him banned from every bar in North Beach, except the old Hawaiian Bar, located directly across the street from the old Co-Existence Bagel Shop. It was only here and in Chinatown where he could go to enjoy a drink and cigarette. But the Kaufman of the 80s was a tired Kaufman. As early as l965, he wrote, “My body is a torn mattress/disheveled throbbing place/for the comings and goings/of loveless transients/before completely objective mirrors/I have shot my self with my eyes/but death refused my advances.”

There wasn’t a lot of conversation between us, but there didn’t have to be. His eyes said it all. Many times we would pass each other on the street, looking each other directly in the eye, and exchange a knowing smile. That look was more than any words could describe. He also had a magical way of appearing from out of nowhere. I would be sitting at a bar enjoying a drink, and suddenly I’d see him standing there beside me, having seemingly appeared from out of nowhere. Sometimes he would ask me for a cigarette; sometimes he would take a seat next to me and mumble to himself, or recite poems from the masters like Pound, Eliot, and Blake. He had memorized their work by heart.

Kaufman had a great influence on me. I recall an occasion in the early Seventies. I was standing at the back of the Coffee Gallery, listening to a poet read his work at the weekly reading series, when suddenly from behind, I felt a hand on my shoulder. It was Kaufman.

“Are you going to read your work tonight? ” He asked. I hadn’t planned on reading that night, and said that I had not brought any poems with me. He looked me in the eye and said, “I came to hear you read.”

I left the bar and drove several miles across town, in a driving rain storm, to my apartment, to pick up some poems, convinced that he would be gone by the time I returned, only to find him sitting alone at the back of the room, seemingly caught up in a private conversation with himself. I read several poems that evening, very much aware of his eyes on me, and finished the reading by dedicating the last poem to him. When I finished the poem, I looked over at the table, and saw that he had left the bar as quietly as he had appeared.

Until that evening I had been reluctant to read in public, and I think he must have sensed my insecurity. From that night on, I became a regular reader at The Coffee Gallery, and had Kaufman to thank for helping me overcome my fear of reading in public, a phobia that had followed me from grammar school into adulthood.

Kaufman’s humor showed not only in his poetry, but in his life as well. I recall the time he walked into the old Coffee Gallery where Gregory Corso was holding court and enjoying the admiration of a group of young admirers. A young woman asked Corso to name the major poets of his era, and he began rattling off several names, which not surprisingly included his own, while identifying Kaufman and Micheline as minor poets. He was unaware that Kaufman had entered the bar, and was standing near the doorway. I turned in Kaufman’s direction and asked him where he would rate Corso. Without hesitation, he smiled and said, “Major Minor,” exciting the bar to loud applause.

I recall yet another time at the Vesuvio Bar, located next to City Lights Book Store, when a tour bus filled with tourists double-parked outside the bar in order to allow the passengers to debark and use the establishment’s restroom. As the small group of middle-aged tourists departed the bus and made their way into the bar, the tour guide began his rehearsed speech:

“This is where the Beat Generation began.”

Suddenly Kaufman leaped up on one of the tables, and shouted in a loud voice:

“No. No. Alice Toklas was commissioned by the Pope to do a book, and Gertrude Stein jumped out of the looking glass, and declared it the Beat age.”

The tourists quickly left the bar, probably thinking Kaufman a mad man.

I had a special place in my heart for him. There was something mystical about the man. I recall yet another night in the Seventies when I was stoned out of my mind on a combination of alcohol and “downer’s,” a suicidal combination. I was staggering down Green Street, headed for Gino and Carlo’s bar when I passed by what had once been the Anxious Asp, when a shadow jumped out at me from the darkness of the doorway. It was Kaufman dressed in a Mexican poncho.

He reached out and firmly grabbed my arm. Before I could say a word, he said in a soft tone, “A.D., Crazy John, a great book.” Then just as suddenly he disappeared down the street. He was referring to a recently published book of mine, The Further Adventures of Crazy John, which I had given him a year earlier. It was a surreal experience that I’ve never forgotten. This incident helped turn my life around. The next day I began work on a long prose poem (America), which is one of the strongest political poems I have written. I would later read the poem at a benefit reading for Kaufman, held at the Little Fox Theater, to a crowd of more than 300 people. Kaufman’s smile contributed to one of the strongest readings I’ve ever given.

I was sitting at Spec’s Bar in North Beach the night that Kaufman is said to have officially broken his vow of silence, appearing from out of nowhere. I watched him eye the crowd, many of whom were waiting to go to a party being hosted by Miriam Patchen, Patchen’s widow. Within moments of his entrance, Kaufman launched into a spontaneous recitation from the works of T.S. Eliot, William Blake, and Ezra Pound.

Despite the drugs and past forced shock treatments, he was still able to recite the old Masters from memory. I sat there watching the veins on his neck stand out with each poem he read.

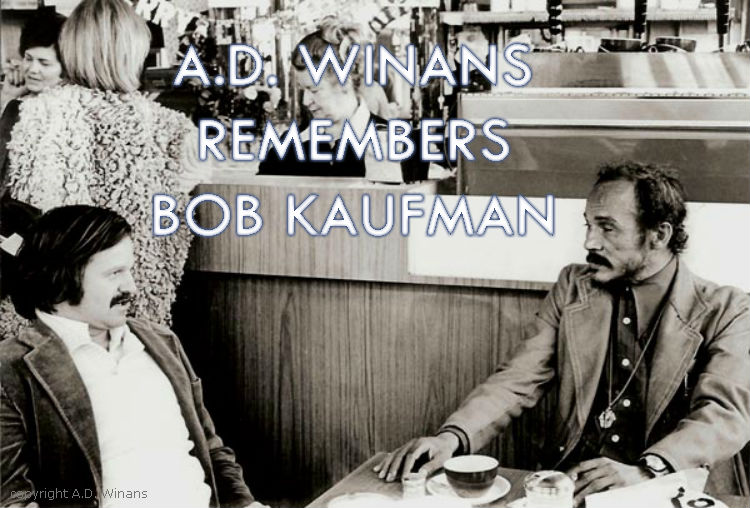

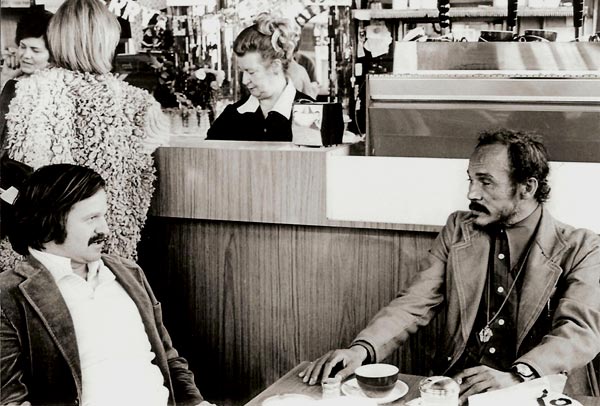

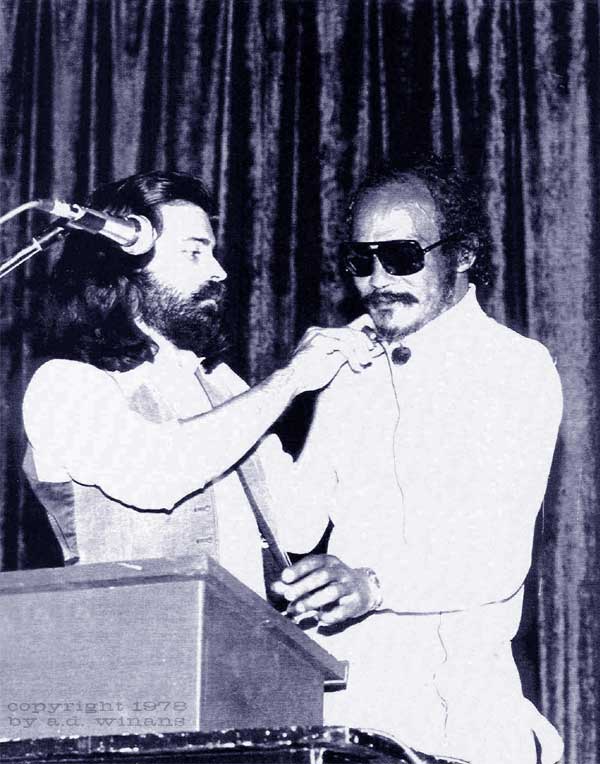

This was to be Kaufman’s last hurrah, although there would be benefit readings, like the 1978 Street poets reading, which I organized at the University of California Extension Center. The reading featured Kaufman, Jack Micheline and myself. The day of the reading Kaufman was a twitching ball of nervous energy. In order to make sure he would show up for the reading, it was necessary for me to pick him up in North Beach and keep him company until the time of the reading.

We were having a cup of coffee at a nearby coffee shop when he began mumbling something about La Guna Honda. La Guna Honda is a County hospital and old age home. I had a cousin who had been forced to spend her last days there, and knew what a depressing institution it was. I was aware a friend of Kaufman’s had recently been hospitalized there. With hours to spare before the reading and tiring of the coffee shop, I on the spur of the moment decided to drive to La Guna Honda Hospital. The grounds themselves are quite beautiful, unlike the inside of the institution.

I parked the car at the lower end of the grounds, and turned the engine off, when suddenly Kaufman started reciting The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock . In my mind I believe he was paying a final tribute to his friend. Afterwards we drove back to the coffee shop, and found ourselves joined at the table by Eileen Kaufman. Kaufman hadn’t said a word since spontaneously reciting Eliot’s poem. Eileen was excited about the reading, and had brought a tape recorder with her, to record the reading. Kaufman several times looked anxiously from Eileen to me.

Don’t give Eileen the money. “You pay me,” he blurted out. He repeated this sentiment several times until I assured him I would pay him and not Eileen. In fairness to Eileen, she was only looking after his interest, knowing that after the reading he would return to North Beach and spend the money on his drinking friends, but I felt it was his money to spend as he wished.

Back then North Beach regulars were a funny lot, seldom leaving the safety of their neighborhood, but for this special occasion, they came in great numbers to hear his magic one more time. He didn’t disappoint them.

He stepped up on stage to loud applause, and almost instantly I realized he was revising his poems on stage. This is a remarkable feat, especially for someone in his condition.

The one thing I was able to accomplish for Kaufman was to assist him in obtaining an NEA writing grant. In the Seventies, at the height of my publishing success, I was on good terms with Leonard Randolph, the Director of the NEA Literature Program, who wielded considerable power. It didn’t matter what the grant’s panel decided, if Randolph wanted you to receive a grant, you would receive it. I knew this when I approached Randolph, and informed him that Kaufman deserved a writing grant, and considered it a done deal when Randolph turned to me and said, “Have someone fill out and submit the grant application.” I have since heard others claim credit for Kaufman receiving the grant, and that’s fine with me. The truth is that Kaufman deserved the grant, strictly on the merits of his work and not the influence of others.

The late Lynne Wildey provided Kaufman shelter and companionship in the last years of his life. I never saw him much the last two years of his life, after he moved out of North Beach. Being the warrior he was, he fought off the advances of Lady Death, until January l2, 1986. I was in North Beach celebrating my fiftieth birthday, walking down Grant Avenue, when Shig (the former manager of City Lights) stopped me on the street, and informed me that Kaufman had died, at the age of sixty, a victim of emphysema.

My first reaction was one of shock, then rage. Again the heavy hand of death had come to claim another victim. I found myself walking from bar to bar, informing first one and then another person of Kaufman’s death. The reaction was the inevitable “shit” or “God Damn.” The truth is that death is not a good conversationalist.

As I walked down the street to the Vesuvio Bar, I recalled the last time Kaufman and I had drunk together at North Beach. We were sitting at a bar in Chinatown, when he asked me if I owned a radio. When I replied that I did, he looked at me, and said, “You can listen to jazz.”

Not a surprising statement, for jazz was a big part of Kaufman’s life. He knew many of the great jazz musicians and his poetry was literally filled with jazz.

Kaufman will be duly recorded by Beat historians (and honored as he was in the Whitney Museum Beat Art Exhibit), and rightfully so. The shame is that his Beat peers, caught up in their own egomania, made little effort to see that he gained the full recognition he deserved.

Kaufman once said, “Why turn a perfectly good frog into a princess” and privately confided to me years earlier, “Death is hunting me down.” On Sunday, January 12, 1986, the hunt ended.

On Friday, January 17, 1986, they came from all over—250 poets and friends—to pay their last respects too perhaps the most prominent black Beat poet of our time. The predominately white background faced a black priest and jazz group at San Francisco’s Sacred Heart Church, near the black Fillmore district. Ferlinghetti read a letter from Allen Ginsberg, who was in New York, and unable to attend the memorial, and Michael McClure read a poem of Kaufman’s. Bob’s son, Parker, a part-time model, told me that simultaneous ceremonies were being held in France, New York, Belgium and Germany, designed to coincide with the San Francisco memorial services.

I thought it odd seeing him eulogized inside a church, since he had been a self-proclaimed atheist, and the lines from one of his poems came to my mind: “God, you’re just an empty refrigerator/with a dead child inside, incognito/in the debris of modern junk pile.”

Jack Micheline read a poem for Kaufman, outside the church, to a large crowd, while a Municipal bus drove by with confused passengers peering out from behind the windows. I don’t think Kaufman would have been upset about the eulogy being held in a Catholic church. He may even have been amused.

At noon, perhaps one hundred of the mourners gathered at the Mirage Bar at 22nd and Guerrero Streets, for a sharing of camaraderie that lasted well into the evening. At 10:00 p.m., Parker’s son and I, and a mutual friend, went for a quiet neighborhood dinner and the sharing of fond memories.

Kaufman’s ashes were scattered at sea on Thursday, January 23, 1986, according to his wishes. Earlier a jazz procession made their way up Grant Avenue, stopping to play music at each of the bars Kaufman had once drank at.

Kaufman maintained his sense of humor right up until the end. Lynne Wildey told how she had visited him shortly before his death. She said as she was preparing to leave, Kaufman looked up at her, smiled, and said, “Stop by the next time you’re in the neighborhood.”

The Beats had lost one of its proudest warriors. If Tony Bennett left his heart in San Francisco, Kaufman left his in the streets of North Beach.

POEM FOR BOB KAUFMAN

he walked the streets of North Beach

an ancient warrior with hollow eye sockets

that seared the dazzling lights of the city

of Saint Francis

his eyes boring into you like a silk worm

carrying decades of heavy sorrow on his back

like a bent over hunchback

overcome with the rust of time

flesh stripped to the marrow

the mirror of his eyes doing a slow dance

up and down Grant and Green

a dark shadow riding clouds of

“Ancient Rain”

his life measured in hot jazz and verse

a surreal mirage where hips cats

wailed in perfect rhythm

as he walked an imaginary zoo

looking for tigers to talk to

runaway poems blaring in his ears

like a stuck car horn

the Ancient Rain falling

washing away his wounds