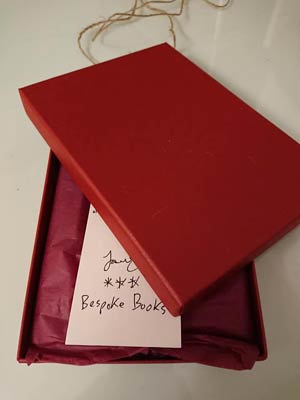

Celia Galey recently caught up with Jason Stoneking in Paris, to talk with him about his current series of unique, handwritten, Bespoke Books. The interview is transcribed here.

Celia: So first I wanted to go back in time, to when you started thinking about the Bespoke Project. When was that? What it is that you were looking for? A new form, a new practice, a new context for writing, a new circulation mode?

Jason:

Well, in my previous writing project, I had been asking readers, colleagues, friends, other artists, to give me subjects to write about, with the idea that if I was directing the content at one specific reader that it might open up some sort of channel, or a spectrum of different voices that might emerge from me. So I was really interested in the idea of targeted writing already. And when I first thought about this project specifically, I guess it was in 2016. I was in a relationship with a woman, and I went home for Christmas. I was going to be in the United States, out of her company, for a few weeks, and I thought it would be a nice Christmas gift for her if I kept a journal of my time there and then gave it to her when I got back. And so I kept a journal by hand, of the whole trip, and all the things that I wanted to say to her. And when I brought the journal back and presented it to her, the look on her face when she got it… She said to me, “You gave me a whole book, you wrote me a whole book!” And I thought, wow, yeah, that’s it. That’s the feeling I want to provoke. That’s the sort of immediacy with which I want to write, and the intimacy with which I want to write, but also the kind of object. When you get a copy of a Stephen King book from store, that specific object is not meaningful to you, but this book was meaningful to her. And I thought wow, that’s it. A light went off, and I thought, why don’t I just start writing whole books for people by hand?

Celia: And how did you come up with this name, “Bespoke”? Did it carry a cultural, political, economic, artistic, literary, vision of yours? Because obviously what you just told us about is a very personal situation. How did you think you could take that into other forms of relationship, with addressees that you would maybe not know personally? And how did that change the scope of the project, or its meaning?

Jason:

I love that you brought up the idea that there are potentially sociopolitical ramifications in the wording that’s used there. The origin of the name of the project was a conversation with Mark Fitzpatrick, the Irish novelist who lives here in Paris. He and I were talking a lot about the project at its inception, and I was looking for a title and sort of struggling with that. I wanted something short and punchy, catchy, that explained as quickly as possible what it is about this kind of book that’s unique. And I kept coming back to the idea that it’s for one person, that it’s made to order, and that no two are the same. And it was Mark who finally said, “But they’re bespoke books; that’s what they are.” And I thought it was great. I mean, the alliteration and the whole thing seemed so intuitive that I just took his idea and I ran with it. So the origin of the name was really that simple.

But where it hits on what you’re asking about, about the broader reaching scope of the words, is that later on I started encountering a lot of people who weren’t familiar with the word bespoke. And I had to deal with the idea that maybe that word was a little bit exclusive, you know? And then I started finding other people who were really familiar with that word, but were familiar with it in terms of things like custom made jewelry, custom paint jobs for luxury cars, and things like that, and I thought ouch, not good. And I think, actually, if anything, the more feedback I’ve gotten about that word, the less comfortable I’ve been with its positioning in terns of sociological questions, political questions, economic questions. Maybe that word isn’t conveying, as accurately as I might have thought, everything that I was hoping to convey. But at the same time, the word means what it means. And the books are bespoke. And a writer can’t be afraid to use a word to mean what the word means. And so, rather than shy away from those sorts of emerging challenges, I’ve just decided so far to keep the name of the project and roll with it.

Celia: How would you explain how this project differs with other self-publishing practices, as we see with books, or self-branding on social media? How would you situate yourself among these practices?

Jason: As far as a differentiation from self-publishing, really, I’m not publishing at all. And perhaps the real articulation of that is that the books that I write, when somebody orders them, they don’t just receive the only copy of the text, but they receive the rights to disseminate or reproduce that text if they wish. So the decision of whether the book will ever be published actually rests with the recipient of the book, and not with me. Instead of being one of these people who has written something and “now I’m gonna put it for sale on the internet, put it on every social media platform, and try to get as many clicks as possible,” it’s absolutely the opposite. The piece that I’m writing, I’m not the one seeking attention for it. The person who commissions it has control of it, and if they want to type it, publish it, put it on the internet, read it on YouTube as a couple of people have, they can. But they’re the ones who decide, and not me. So there’s quite literally no self-publishing going on.

Celia: Why is it important for you to know the books have a life that you can’t control, and you can’t predict, once you give them away?

Jason: I’m glad you asked that, because nobody has ever asked me that before, and it is something that’s very important to me. One of the things we see going on in the self-publishing revolution you mentioned is that people are putting dissemination before content, and they’re also putting ego gratification before content. People want to get clicks, and they want to get likes, and they want to get validation, and that tends to come from the promotion of the work rather than from the work.

What I love about this project is that the work has to promote itself. It’s not me saying that because I wrote this text I want 10,000 people to read it. I’m not sending copies to the four corners of the world, putting it on blogs everywhere. I don’t even have a blog. What I’m doing is just writing something, trying to touch the person I’m writing to. And if that person feels so touched and so moved by the strength of what I’ve written that they feel compelled to preserve it, and share it, then the text has done a mighty job. And if they don’t, then why should it be seen by more people?

So I guess what I want the text to do is to go out there and earn its own preservation, earn its own passage through life, by proving its quality to the person who receives it, and not just by being promoted by me for the validation of my own agenda and my desire for money, or recognition, or fame, or whatever it is that I might be trying to do.

Celia: So, how would you feel if one of the recipients decided to mass-produce one of your books? I mean, wouldn’t you be worried that it might be detrimental to you or to the project in aesthetic or political terms? Or would it be possible even for one of the recipients to decide to mass-produce at their own expense, and then benefit from it economically?

Jason: Absolutely, yeah, they are welcome to do that if they would like. So far nobody has mass-produced anything. There has been somebody who read the entirety of the book that I wrote for her on YouTube. And there was somebody else who scanned an entire book into photos and then posted them on the Facebook page for the project. So there have been people who have made the works that they received publicly available. But so far nobody has physically mass-produced one of the books. And if somebody did? I don’t find that problematic for my purposes. Again, it’s up to them. What they would be saying is that they want to give wider reach to something that has been meaningful to them. And I think I would be touched. I would be honored that somebody wanted to do that. But I prefer not to be the person who makes the decision of mass-producing the work. I’ve done that before. Self-published a book, made many copies, traveled around giving readings, and every night, had to open the trunk and see that huge box full of identical copies of my book that had all rolled off an assembly line somewhere in some factory. And I had been the one placing the order. I had been the one deciding how widely my work should be distributed. I felt somehow uncomfortable with that responsibility. And I thought maybe it would be more interesting for this project if it was the reader who had the ability to make that decision.

Celia: It’s funny that you say that you were uncomfortable with that responsibility. Why?

Jason: Because… If somebody is going to print 10,000 copies of a book, they’re saying something. And I’m not sure I want to be the person to say it. I think it’s a bit uncomfortable when somebody says, “I think you all should read my book.” Or even just, “I think you all should read the same book.” Because I’m not sure how true that is. We don’t all have the same favorite David Bowie album. One of the really interesting things that’s happening in literature right now is the challenge and the deconstruction of the canon, and people starting to ask the question, “Why do we all study the same writer?” Particularly when the writer is an old white dude, and everybody’s going, “Really? We all still have to be interested in this?” What I don’t want to take responsibility for is publicly endorsing the idea that either I am the writer, or that this is the book, for a certain size of audience. I like the idea that a specific reader tells me they would like a book by me, and then they get one. Then, if that book creates a wider demand for itself to be read, because of the effect it has on that reader, because it’s successful for the person who wanted it to begin with, then that’s great. So be it. I would never block the dissemination of my work. But if I write a book for one person, I’m not necessarily going to tell 10,000 other people they should read it, when there might be another text out there that connects more directly with their experience, or with what they want to be reading about.

Celia: So it sounds like you’re going beyond just the idea of commissioned books, like you might have with Renaissance art, having a patron commissioning artworks. It seems like you’re more concerned with the authenticity of the relationship you have with a specific addressee. Is it a dialog? Is it a triangle between you, the addressee, and the book? How do you perceive it?

Jason: I suppose I am somewhat influenced by the Renaissance idea of commissioned portraiture. Somebody getting a painting that was done just for them, and then having the only extant copy of it. I think that’s exciting in its rarity, and its directness. And hopefully the object itself reflects a certain directness, or immediacy, between the artist and the subject. But I suppose what’s important to me to explore, in terms of authenticity, has really been something that’s vexed me since I was a teenager, which is this idea that when I’m writing something for a generalized audience, I don’t know how to pitch it. It doesn’t feel like the truth of how we speak. When I’m speaking to a friend I speak one way, when I’m speaking to my mother I speak another way, when I’m speaking to a lover I speak another way. Which is not to say I feel inauthentic in any of those situations, but a register of vocabulary might change, a register of attitudes might change. Common references change things. If I was speaking to an American audience, I wouldn’t tell them what Seinfeld was. If I was speaking to a French audience, I wouldn’t explain who Charles Aznavour was. But not knowing who you’re speaking to, I always found a bit crippling, in terms of how to establish a vocabulary of reference before proceeding to try to deliver something really intimate. I’ve been told in the past by my friends that texts I had written to them privately felt more powerful to them than the stuff I wind up publishing. So maybe the light bulb that went off when I wrote that first handwritten book was that the important thing is just to do my best writing, and find the format that allows that.

Celia: It sounds like there’s nearly an epistolary dimension to these books. I was wondering why it’s important for you to keep a book, or notebook format. Why, for instance, wouldn’t you explore, for example, a scroll. I know you’re interested in the Beats. We haven’t tackled that subject yet. But I was thinking of On the Road, the manuscript, this very long scroll. Is there something important for you about the turning pages, about the inscription of the reading in time?

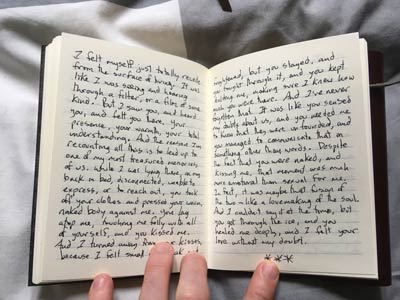

Jason: The materials I’m using are just the ones that I’m personally most comfortable with. When I was a teenager, I would constantly write in a journal. Every day I’d carry it around. This was before the internet. I was traveling around the States in the 80s and early 90s as a teenager, with a notebook in a backpack, and constantly stopping to write in it. On the bus, on the train, in a car while I was hitchhiking. On the beach, in a phone booth in a rainstorm. For me that object, the journal, the notebook, the diary, the bound book with the lines in it, became kind of sacred. It takes me back to my earliest passion for writing. It was the first material I worked with. And I feel like the more I got into working directly into virtual space, doing type-written first drafts, working with word processing and things like that, the more I got away from the commitment I had felt when a pen would touch a piece of paper. There was no retracting that act. There was no taking it back. When you’re typing something onto a screen, you can erase it before you hit enter, and then it never happened. But when you’re writing with a pen, either you keep going or you cross it out. But either way, it’s there forever. And that, for me, heightens the stakes of the experience of writing. And it rekindles the passion I felt when I started writing. And I want to preserve that passion in the object that I deliver to the reader.

Celia: Do you write drafts for the Bespoke Books?

Jason: No. No drafts. No notes. Nothing. What the reader gets is the first and only original draft of the text.

Celia: So clearly your writing in this project is not just a strictly textual thing. So what would you say it is? Is each of these books the trace of a process? Or is it a performance itself, whose life goes on after you’ve handed the book to the recipient? You’ve said you would relinquish the rights. Are you interested in tracking these books, and keeping a record of what they are becoming?

Jason: Yeah, somebody just asked me that the other day. I’m just starting to get to where I’ve done enough of them that whether or not I’m going to try to remember who has them all is becoming a question. I think I’ve written 25 or 30 of them now. So it’s just starting to get a bit outside my control, and I’m starting to ask myself, do I want to keep track of them? I think I would like to remember who I wrote them all for, and maybe keep a record of that. But I like the idea that I don’t keep records of the texts themselves. It’s interesting you brought up the question of whether the object was strictly textual. And strictly, no, but I think the text is important. There is a way in which the object is the document of a performative gesture, but it’s not merely a performative gimmick. It’s also deeply considered writing. I write with an eye on arc and structure. I think a lot in the process. It’s not always just stream of consciousness. It’s not automatic writing. Sometimes I think for two, three hours about a paragraph before I write it down. So even if the reader gets the only copy of the manuscript, or the only draft of the text, that doesn’t mean that it was written flippantly. I take it seriously as writing, and as a textual effort. And then also, the way it’s delivered is the document of the performative way in which that text was generated. So I’m trying to preserve not just the words but the process behind them. I’m trying to capture the process at an earlier stage than where a text piece is traditionally captured.

Sometimes I think about Jackson Pollock, and how, when he was doing the splatter paintings, really what those paintings were about for me was capturing the gesture, so we could feel where the painter was before the moment of composition. And it’s very rare these days that you see that in text, because the going wisdom is that what’s crucial is editing editing editing. And there’s this whole system of gatekeepers who edit a text six times before it appears in a magazine, or before it’s collected into a book, or before it’s published by whoever decides what to publish. It’s not often anymore that you see writers trying to capture an earlier stage in the creative process and preserve that to share directly with the reader, even though in many other art forms that’s quite common.

You still see the sculpture that’s been partially freed from the marble, or the abstract expressionist painting, or the improvised dance, or even the guitar solo, which isn’t the written part of the song, but it’s what makes the live band live. But writers don’t seem to have so much an equivalent of that anymore. Even spoken word artists often get on stage and perform word for word, and intonation for intonation, an exact text that’s been performed before. I wanted to experiment with capturing a rawer, earlier stage of the writing process, and making that the finished product.

Celia: It resonates a lot with the poetics of spontaneity we find with Beat poets such as Allen Ginsberg. Is there something you would like to develop on that point? Your relationship with the Beats?

Jason: Yeah, that’s an important lineage for me. I was fourteen, just turning fifteen, when I first left home, and I had just started reading the Beats. I’d read On the Road, Dharma Bums, Howl, and suddenly I said, “That’s it, mom, I’m quitting school. I’m hitchhiking to California. I’ve got it all figured out.” [laughter] I put my notebook in my bag, and I hit the road, and those people were heroes to me at that time in my life. Then, when I was eighteen, I moved to Boulder, where they have the Kerouac School for Disembodied Poetics, at Naropa University. I spent a few summers hanging around there, and during that time, I got to meet and talk to Allen, and Anne Waldman, and a lot of other writers who were influential to me.

One of the things that Allen talked about was “first thought best thought,” you know, the idea of a kind of intuitive poetics. I was taken with the spirit of freeing the natural gesture from inside the self as a starting point for the work. Ideas like stream of consciousness, trying to tap into the deepest, most organic flow of the self.

I remember when I was first reading Kerouac, his use of invented words and onomatopoeia really liberated me, because I thought, wow, you really can just say what you feel, and maybe that’s the direction to dig. Rather than saying a sort of commonplace thing, and then honing it until it’s crafted. Maybe to say the offbeat, unusual thing, and then try to trace it and dig under it, until you get to something rawer and weirder and more idiosyncratic, is the way to dig for diamonds. Allen talked about some ideas like that, so I definitely feel influenced by him.

Celia:

At this point, I think it’s still important to underline how your project relies on skill. It’s not just about you expressing yourself in a very unregulated, unstylish way. How would you define the skill of the writer as the sort of persona you work with, or you work from? In terms of how to balance out that idea of spontaneity with… I mean, it’s a craft, right? It’s not just that you’re a random person who expresses himself?

Jason: Hmm. Craft is a word that I have a funny relationship with, but it’s true that the accent for me is not merely on the spontaneous uncontrolled gesture. Or to whatever extent it is, it’s important to me that work has also happened beforehand. I feel like the person who plays a guitar solo on stage, and improvises that music, has rehearsed the song a thousand times, and they know where the beats are, and they know what the chords are. They know where the spaces are within which they can play. They make themselves capable of improvisation by a great deal of hard work. And I feel like this is a similar exercise. I’ve written thousands and thousands of pages. I’ve been writing most of my life. At this point, I have some strongly developed ideas about what kinds of things I want to talk about, how I want to talk about them. So there is a lot of intentionality in the work. And a lot of times, when somebody orders a book, I’ll think for a couple of weeks about who that person is, what themes I might want to develop between myself and that person, how I would address that person, where I would start. I give a great deal of thought and attention to those structural decisions before launching in. And then, from within the context of that work, I take a spontaneous approach. I try to let the events of each day enter into the text, and let a sort of organic stream of thought enter into the text too, but it’s not just for the sake of that alone that I’m doing it.

Celia: Are you interested in Buddhism at all? Because it sounds like a very meditative state that you enter in.

Jason: It’s funny you should ask that. Allen, of course, was a Buddhist. And there’s a big focus on that at Naropa, which maybe I would have learned more about if I had actually been a student there, and not just a homeless guy who was hanging around in between the buildings [laughter]. I personally don’t have an interest in a structured spiritual or religious practice. I would not, however, be so vain or arrogant as to assume that the things I do don’t overlap with those processes. I think that each religion and each spiritual practice probably aims to codify something of the universal in the human experience, which is what I think most artistic practices aim to do too. So there’s probably some likelihood that all spiritual practices and all artistic practices have funny little overlaps of style and intention. But I’m not interested in presenting my process, or understanding my process, as spiritual or religious in nature. For me it’s a very personal practice that certainly must bear unintentional similarities to other people’s personal practices. But words like religion and spirituality, and categories of religion and spirituality, don’t interest me personally.

Celia: I could have added psychedelics, or use of psychedelics, to enter other mind states.

Jason: I do have a lot of experience with psychedelics, and those experiences have been very important to me in my life. Again, I don’t necessarily refer to those experiences with terms that derive from spiritual and religious traditions. But I have definitely profited from my experiences with psychedelics in ways that inform my writing practice.

Celia: Would you want to say more about that? How so? [laughter]

Jason: Well… At many points in my relationship with psychedelics, I’ve felt like I was delivered to a place where I was able to deconstruct the conscious awareness of my ego, and rebuild it in a very intentional way. And I think that when I’m writing, what I try to do is deconstruct my subject matter, and my relationship to it, and rebuild that in a very intentional way also. If somebody asked me to write about horses, my starting place would be to ask myself, ok, what do I know about horses? And then, why do I really think I know that? Where did I get that information? And why have I never looked under that information and asked myself what ignorance I might be afraid to confess about horses? And that’s where I would start writing my piece. That’s also where I try to start writing about myself and my opinions. From a place of deconstruction and confessed ignorance. And certainly, when I was younger, psychedelic drugs helped me to access that position.

Celia: So to be at the edge of your certainty, the limit of your mind or your knowledge?

Jason: Or even just to destroy certainty completely, to start from a place where the notion of certainty is absurd. And say, ok, I don’t know anything. I have to remember how little I know. And of course that idea of beginner’s mind also touches Buddhism, and probably goes back to Ginsberg’s influence. To remember what we don’t know, to dig into that place and work from there, I think is much more interesting, and much more fertile, than to act like we know something and then start writing about what we think we know.

Celia: So this ego thing seems to be really central to the Bespoke Books. It sounds like each book is really a layer, or one self, one of your multiple selves, that you let go as you hand the book to the recipient. I was wondering if you feel that you lose part of yourself when you give each Bespoke Book? Like you let go of some control on a part of yourself? Or do you see it rather as an expansion of yourself, an ephemeral manifestation that you scatter around like seeds, and the germination escapes your control but somehow it’s still part of you?

Jason: Yeah, I relate to that. I feel like each one of the books is a chapter of my life. I might be writing to a specific person, or even on a theme, but then also, I’m always writing my journal of that time. The things that are happening to me in those days find their way into that book also. So what the person winds up receiving, depending on the length of the book, is a weekend, or a week, or a month of my life that becomes their exclusive property, because I haven’t kept any other record of it. The only thing I’m writing during that time is their book. It’s sort of like finishing your diaries and then handing them off to people, or making a deal with people going in, “Hey, next month I’m going to keep my diary for you, and you’re gonna have it.” Then, like you said, those parts of me scatter around the world, but I no longer have control of what happens to them next. And I think that’s crucial to examining and exploring whether those documents have value. If I keep them all under my bed, then I’m deciding that they have value to me, and I’m tasking myself with preserving that value. And if I’m publishing them, mailing them all over the world, then I’m asserting that they have value for others. But by infusing them with what’s precious to me, then turning them loose on the wind and not administering them afterwards, I’m really allowing, or trying to allow a more objective discussion of whether or not these documents have value to the society or to the other people living in my time.

Celia: It sounds like the addressee, or recipient, is a persona that’s included inside the book. And that person also becomes the curator, or collector, even if they only have one book. Would you also be interested in working with professional curators, and seeing how the project might be altered by this new context of circulation?

Jason: When you talk about working with a curator, in what capacity?

Celia: Where you would write for either an art gallery, curator, or someone who owns a public space, who would like to order a book. So the context would be not as personal.

Jason: I’m very interested in writing for people who have a vested interest in the preservation of documents, who might be interested in some of these questions I’m trying to ask about their value. I would be happy, certainly, to write for art institutions, educational institutions, really for anybody who finds the project interesting. Anybody can ask me for a book and get one. So if anyone who is interested in these questions approaches me and wants to collaborate, I’ll be happy work with them to create a document that suits their purposes. But I’m equally happy if it turns out that I can’t anticipate who the people are that will take an interest in this process. I like the idea that maybe these books will find their way into institutions and become part of a historical conversation, and that maybe they won’t. Maybe they’ll turn out to be more ephemeral than that. Like performance art. Like happenings, which at some point were specifically for the consumption of people who were in the room, then, at some other point, created a curatorial panic: How do we preserve the fact that this happened? Or continue to discuss what it was, exactly, that happened? And can it be repeated? Can it be retrieved from history? I think all those problems are really interesting, and if the people working on those problems took an interest in my work, I would think that was great. But if they don’t, I’m also quite happy to keep making an ephemeral project that’s more about a dialog I’m having with the people around me, and just see where that leads.

Celia:

Speaking of performance art, and physical presence, would you be also interested in, for instance, writing a book under people’s gaze? Or having a residency over a period of time, that would make you participate with the institution other than only through this written trace?

Jason: Yeah, I’m definitely interested in things like writing as a live performance, residencies, and writing books in situ. One of the projects I recently proposed, to a friend who owns a bookstore, is that I could sit in the bookstore and write every day about what happens there, creating a book that would remain there afterwards. I love the idea of being in residence somewhere and keeping a record in the company of others. I have a favorite band called The Bad Pelicans who have a new album coming out, and if they go on tour next year to promote the album, I’m hoping that I can travel with them and write a book about the tour. That’s the kind of residency I would love to do. To spend time around people that I’m passionate about, and creating a document of that time.

Celia: So given that obviously you’re not marketing it in conventional ways, I assume you don’t have a website for the Bespoke Books project.

Jason: I do, actually! [laughter]

Celia: You do?! [laughter]

Jason: I do have all the sort of boring things you would expect me to have. A website, Facebook, Twitter, all that kind of stuff. I do advertise the project, and try to let people know that I’m doing it. Even if I don’t publicize the individual books, I do want people to know that if they want to get a book from me they can.

Celia: So you take online orders, provided that you meet the person, or talk with the person before you write the book?

Jason: That’s a good question. I don’t always meet or talk to the person before I write the book. I give people the choice, if they want to talk to me about who they are, or the themes that they’re wrestling with. This week I’m writing a book for an actor who told me that he’s working on a project about patience, and he asked me if I would write something about that. So I’m incorporating my reflections on patience, as well as the events in my own life, and what I know about him, which actually isn’t very much because we only met one time. So I’m open to the person telling me about themselves, online or in person, or making a thematic suggestion. But I’m also open to them just letting me handle it. I’ve had a couple of people order a book who just said “surprise me.” I think already the fact that I’m an American hanging out in Paris, and writing books by hand, is a weird enough experience that for some people just hearing about that already has a certain interest. But I like to let it be the reader’s decision how much they want me to know about them before I start. Then ultimately, after reflecting on that, it’s my own thoughts that come out anyway.

This video was made by Maysan Nasser, a young poet in Beirut, in which she reads aloud the entirety of the Bespoke Book I wrote for her after a day we spent together. The video title differs from the book title.

Leave a Reply