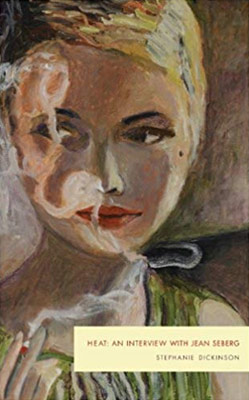

Authors Rosalind Palermo Stevenson and Stephanie Dickinson converse about writing through the personas of Franz Kafka and Jean Seberg.

Rosalind Palermo Stevenson: Stephanie, your poetic and deeply imagined book, Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg, is an intimate and revealing rendering of the legendary actress written in the form of a fictional interview. In my book Kafka At Rudolf Steiner’s I imagine Kafka’s visit to Rudolf Steiner and his idealized ten-day love affair with a young Italian girl while at a sanatorium in Riva. We both juxtapose real and invented details and use the first person point of view to write directly in their voices and personas. I wonder if you might talk about what drew you to Jean Seberg and about your choice to use the first person point of view.

Rosalind Palermo Stevenson: Stephanie, your poetic and deeply imagined book, Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg, is an intimate and revealing rendering of the legendary actress written in the form of a fictional interview. In my book Kafka At Rudolf Steiner’s I imagine Kafka’s visit to Rudolf Steiner and his idealized ten-day love affair with a young Italian girl while at a sanatorium in Riva. We both juxtapose real and invented details and use the first person point of view to write directly in their voices and personas. I wonder if you might talk about what drew you to Jean Seberg and about your choice to use the first person point of view.

Stephanie Emily Dickinson: I was drawn to Seberg or perhaps she was always there drawing toward me, the small-town girl who had escaped the chicken-noodle-soup-supper culture of Iowa to become a film star, a French-speaking ex-pat in Paris. My mother often spoke of Jean Seberg, who grew up in Marshalltown only a few towns distant from the farm where my own childhood had marooned me, a girl picked from 18,000 others to star in Otto Preminger’s Saint Joan. That she had been crowned a celebrity, a movie role lifting her from the faceless amorphous mass into the realm of the gods, mattered less to me than her sophistication, artistry, and self-possession. None of this could I see around me. How had she transcended the place of her origins where the plain-spoken and the practical took primacy?

It was her seemingly crystalline self-creation that mesmerized me–an articulation in her speech and manner of an artistic aesthetic. She projected the possibilities of the exotic, the mysterious, the international as opposed to the regional and provincial. Seberg had catapulted herself free of the soil of her place of birth, but how had she done it? Who was she? The third person would not travel where I hoped to go. Her qualities changed over time or perhaps her vulnerability had only been masked by the armor of youth. Although I couldn’t yet articulate it I hungered for a cultural chic, for style, for an appreciation of beauty. Seberg epitomized intelligent elegance. And in her downward trajectory, she fascinates. Her journey into a hellish chaos, a personality misshapen by fame, her generosity which never wavered.

I wanted my narrator’s position to be embedded in Seberg, her eyes, her taste buds, her pelvic bones. Originally point of view comes from the Latin, but the German word is Gesichtpunkt, meaning face point or where your face is pointed. There wasn’t really a weighing process that went on in my mind when I began writing and researching my imaginary interview with Jean Seberg, I wanted to inhabit her. The first person “I” was my face point.

RPS: I love the idea of point of view meaning where the face is pointed – the face and consciousness. Like you I didn’t engage in a weighing process when I used the first person. A voice and rhythm, along with the book’s opening lines presented themselves in the first person when I began. That close distance of the first person, to some extent a dissolving of distance, seemed to direct the flow of language. The intimacy of the first person seemed to give me sufficient distance to place the real person in a fictional context.

I had been rereading Kafka’s diaries and was drawn to the spare but candid entries about the young woman he had a romance with during a stay at the sanatorium in Riva. That set the process of imagining in motion for me. Then when I read the diary entries written on March 26th and March 28th, 1911, I was struck by the fact that Kafka had attended Rudolf Steiner’s lectures on mysticism when Steiner was giving them in Prague and had visited him at his hotel. In the diary entries related to Steiner, Kafka refers to his own clairvoyance. I began to work with the idea that some portion of the dark forebodings in his work, the autocratic and tyrannical forces that overwhelm the individual, might come out of a precognition on his part of the coming evil that would soon overrun Europe. That idea fed into the book’s atmosphere and much of its imagery.

I had been rereading Kafka’s diaries and was drawn to the spare but candid entries about the young woman he had a romance with during a stay at the sanatorium in Riva. That set the process of imagining in motion for me. Then when I read the diary entries written on March 26th and March 28th, 1911, I was struck by the fact that Kafka had attended Rudolf Steiner’s lectures on mysticism when Steiner was giving them in Prague and had visited him at his hotel. In the diary entries related to Steiner, Kafka refers to his own clairvoyance. I began to work with the idea that some portion of the dark forebodings in his work, the autocratic and tyrannical forces that overwhelm the individual, might come out of a precognition on his part of the coming evil that would soon overrun Europe. That idea fed into the book’s atmosphere and much of its imagery.

Helénè Cixous, in referring to her plays, talks about writing people who are ‘fictitious but real.’ We have written people who are real but at the same time fictitious by combining what is known with an imagined unknown.

SED: Ultimately there is so much that is unknowable about a human personality. In many ways we are even unknowable to ourselves although we see patterns of our behavior. I think in both Kafka and Seberg we are pushing back against the notion of the mass which relegates the individual to will-of-the-wisp figments. We are insisting on the primacy of the idiosyncratic—the individual. To fictionalize or to expand on something both known and unknown and to remain faithful to one’s sense of the individual requires an immersion and for the writer to expand the boundaries of the known to get inside. Perhaps remaining true to the individual and stepping outside the known into the unknown are the two main challenges in recasting the iconic into fiction.

I suspect that with Seberg my immersion into her lore was much easier than yours into Kafka as there is so much less available. I read the few biographies and the books her second husband, the celebrated French novelist, Romain Gary, wrote that touch upon Seberg’s relationship with the Black Panthers. I scoured the Internet and watched her films. When the process of immersion begins, it’s odd how you feel almost as if this person belongs to me and I to them.

RPS: I agree it’s the expansion of the boundaries of the known that lifts into ‘story’ and allows for the inward-turning vision of the writer. I think that the life-on-the-page of a narrative always seems to emanate directly from a kind of ‘embodying’ – in some way the writer must submit to, be embodied by, or embody the character being given voice.

When I was writing Kafka At Rudolf Steiner’s the facts about Kafka came from his diaries, as well as from biographical and historical sources. We know from the diaries that he attended Steiner’s lectures in Prague and visited him in his hotel. But we know little about the details of that visit. The same is true about his love for the young girl. There are only three brief entries in October 1913 in which he references her, and in one of them he does not reference her directly. So the related diary entries provide almost nothing by way of details about these incidents. But they do, along with his letters and fiction, provide a window into his sensibility. This established my groundwork for invention. Would he be likely to say this, do this? I invented within the realm of what I thought would be plausible and true to Kafka. But I don’t think there is just one way. I can imagine another kind of Kafka story, a highly speculative piece, in which plausibility is established completely from the interior construct of the piece itself and would be wildly outside of any kind of external reality or anything factual.

Kafka in one diary entry says, “I, at present, already so unhappy.” Seberg commits suicide. It seems to me that in different ways they are both victims of the life they are given to live.

SED: Kafka, perhaps less so, but certainly Seberg, has been called a victim. Kafka, portrayed an ultimate victimization in The Metamorphosis, the son as a cockroach with an apple thrust in his side. The whole notion of “victim” is one that I think needs unraveling right down to the language level. It’s a culturally loaded word, and implies powerlessness. Are we using Victim as one who has been harmed, Victim as one who has been duped, or Victim as in a living creature killed as a religious sacrifice? I wonder if it’s not most appropriate to think about Kafka and Seberg in terms of the sacrificial victim, i.e. the dictionary’s third definition—a burnt offering. A scapegoat, a heaping on of the epoch’s anxieties.

In the late 50s and early 60s we have the epoch’s anxiety about the civil rights movement and its power as a force for social change. Seberg’s support of the Black Panthers and the FBI’s surveillance and relentless war against her are now the subject of a new movie called Against All Enemies. I believe for a writer it’s not only about exploring the iconic personality but venturing into their cultural petri dish, breathing the air of an older time. This was my objective when writing Heat. And this I think you’ve done in Kafka exemplifying with language, syntax, and word choice, an early 20th-century European milieu. The exploration is a kind of time travel where the mores of the epoch are made flesh.

Seberg lived as a woman ahead of her time and was censured for acts that would in the next generation be commonplace. Her life was a bridge between then and now. Experiencing the era even vicariously, you walk through the fog of misogyny. An exemplar of this–the limited film roles offered women even during their short shelf-life of stardom. Sex bomb or rag and bone character actress Like the equally intelligent Marilyn Monroe and Jean Harlow, Seberg was cast into the so-called “floozy” roles despite her reputation for being smart and cultured and teaching herself fluent French when her high school didn’t. But directors and critics could not see these women without the lens of diminishment.

RPS: Kafka too was seen through the lens of diminishment by his father. So much of everything with Kafka reflects back to his father, who was explosive and who had no understanding of or appreciation of his son’s creative sensibility. I think this too is a form of gender victimization. Kafka was subjected to the tyranny of an expectation about the kind of man a man is supposed to be. He was the only living son. But a son sensitive and brilliant, lacking machismo, and his father all machismo. I think of a description I read of Kafka at the dinner table with his digestive problems and chewing each mouthful of food around 30 or 40 times, which was part of his preoccupation with diet practices for health. His father openly showed his deep disgust and got up and left the table. In my imagination (though not in my book) I extend the scene – I have this image in my mind of Kafka’s father overturning the dinner table. But even without any overturning of tables, the ferocity of his father’s rejection of his son’s way of being in the world could not help but be experienced as violence upon Kafka’s person and psyche.

SED: There are many ways that violence can be enacted. When writing Heat one of the most striking examples of violence against Seberg that I found was her husband Romain Gary’s film in which he cast her and where it is on the beach among dead birds that Seberg wakes to being raped by a stranger who wears a bird’s mask on the back of his head. Romain Gary, who knew the intelligence and spirit of his wife, who knew how self-conscious she was about nudity, wrote a script of unbelievable sexual psychosis which also included nude scenes.

The act of writing often seems a transmutation, the words creating a metaphorical body and mind. This is amplified when the iconic subject is part of the visitation. Since I share Iowa origins with Seberg, I wanted to coax out what her sense of the Midwest was and the possibility of the mythic arising from its peculiar fecundity. I learned through the visitation how her personality mingled falcon and show pigeon, she was both the throat before the cut and the knife.

RPS: There are also choices of containment in this kind of work – for Kafka At Rudolf Steiner’s there is the idea that the work ultimately encompasses only the timeframe in which it takes place, but that Kafka’s life continued on. In my story everything is contained within the time of Kafka’s visit to Steiner and his idealized love for W during a stay at the sanatorium in Riva. So there are the many things that my story does not encompass – not in the sense of being lacking, but in the sense that the reality continues past my story’s borders. That too may be one of the differences in writing through someone who existed in reality rather than through a completely invented character.

SED: I covered the full range of Seberg’s life in adopting her persona. You took two specific incidents from Kafka’s life and made them stand for the whole. Your lens moved close, enlarging gesture and footstep. There are the choices the writer makes in deciding which events best exemplify the personality. Both conscious and subconscious choices. I chose the chronological path and each interview question delves into Seberg’s more clandestine emotions as a 16-year-old, an 18-year old, a 40-year old. The many selves—wife, divorcee, adulteress, mother, actor, activist, friend, alcoholic, hysteric. They are panning shots that move in for the close-up of a mysteriousness such as the child at the Marshalltown Odeon Theater hungering for the far away, the 39-year old drinking at Le Boucanier until she passes out on the floor.

RPS: So much of a real life cannot come into a book. I recently reread “Josephine, the Singer, or the Mouse Folk,” one of Kafka’s very late stories. And also the Letters to Family and Friends. I was taken, particularly in his story “Josephine the Singer…” by a kind of increasing sweet-heartedness in Kafka as he continued on in his life. There is something gentle in this story, and then the wonderfully philosophical ending.

And in the letters, in that last section of letters when he was dying in the sanatorium, they were called “conversation slips” – he wrote them because he could no longer talk – just little bits, his part of the conversation on small slips of paper – it is a sadly powerful experience to come face to face with him dying 11 years after my book ends – to see how much pain he was in, how he could no longer talk, how he couldn’t eat, he could barely even drink water. But again his gentle and kind-hearted nature, his absorption during that time with flowers, he devotes much of his time of dying to flowers. On the “conversation slips” there are written such things as: “I’d especially like to take care of peonies because they are so fragile.” “And move the lilacs into the sun.” “Do you have a moment? Then please lightly spray the peonies.”

SED: Kafka’s “conversation slips” echo in Seberg’s life, as well. That both of these communicators of language, one written and the other spoken, would approach the end with a smattering of words moves me deeply. How potent those last communiqués, thought symbols to the outside world. Seberg committed suicide in the backseat of her Volvo that had been parked on a quiet leafy street. Undiscovered for days, only the trees watching, her body was finally taken to the Paris morgue, where examiners extracted the note addressed to her son clutched in her hand. “Diego, understand me. I know that you can and you know that I love you. Be strong. Your loving mother, Jean.” I was struck by the word Jean just as I was by Kafka’s phrase, Then please lightly spray the peonies. They’re sign posts into the interior. They resonate as only words able to envision the unthinkable can.

RPS: I’m always struck by the force of life itself in relation to Kafka – that is, the role of life or what we might call fate or destiny with regard to his duration in time. Shy to a point of seeking invisibility, self-effacing, living most of his life with his parents, rarely leaving Prague, wanting his work to be destroyed when he died, and now so widely known as to be almost a household word, familiar to those who have never read him, even to those who don’t read, he has even become the adjective Kafkaesque.

SED: Seberg too continues to speak to the 21st century. Google Jean Seberg and you’ll discover she’s been given a second life on the Internet. You can hear her musical voice speaking French and watch trailers of Lilith and Bonjour Tristesse. There are fashion blogs featuring photos of Jean Seberg’s Breathless apparel. You can listen to Jean and Romain Gary discussing in French their marriage with an interviewer. You can join in comment threads arguing the FBI’s surveillance of Jean, good or bad radical politics. The Seberg brand has gathered new energy in the 21st century. Google Jean Seberg and you’ll find hundreds upon hundreds of photographs, quotes, trivia quizzes, bloggers who lionize Jean as a style icon.

RPS: I’m reminded of this quote about icons by Sara Holdren: “There’s a word in Russian: obraz. Translated simply it means image, but more accurately it refers to an icon or a sacred image, an image replete with expansive figurative meaning. More than a symbol, an obraz is an instant that contains an entire cosmos.” I think with cultural icons too, with Kafka, with Seberg, there is inherent in them the idea that their lives were an instant that contained an entire cosmos.

Leave a Reply