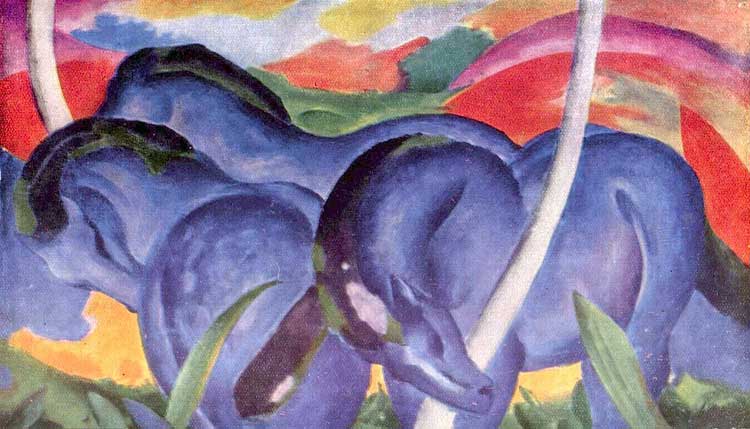

A painter and writer who was born and lived most of his life in Bavaria, Franz Marc was one of the key protagonists in the great European debate on the nature and the goals of art at the beginning of the 20th century. Marc’s and Wassily Kandinsky’s 1911 hybrid art-book the Blaue Reiter Almanac was immediately hailed as a turning point in the practice of artists providing theoretical frameworks for viewing their work, and thus in the discipline of art history itself.i Because of Marc’s famous contributions to the Almanac and his tendency to produce in prose a tantalizing amalgam of passion and wit, his writing is seemingly easily accessible and has been categorized in German scholarship simply as an artifact of Expressionism.ii

Since his death in 1916, several circumscribed collections have been published of Marc’s letters and essays. While clearly the animal has the central position in Marc’s painted oeuvre, I maintain that his writing is both more expansive and less quantifiable. Because of the association with Kandinsky’s “breakthrough to abstraction,” Marc’s words are most often analyzed with respect to nonobjective painting. His writing is presented as a straightforward part of the canon of Expressionism, and is thus stilled, under-analyzed, and largely forgotten.

In this article, I propose a holistic recovery and new examination of Marc’s writing with a goal of both freeing and rediscovering it in mind. Marc puts forward nothing less than a pantheism for the coming age.

One hundred years after the death of Franz Marc in the Battle of Verdun, the question of understanding the early avant-garde artists poses itself more urgently, yet more amorphously, in our own day than it did even in Marc’s.iii The study of Marc’s life and work may act as a prism through which such questions may be drawn into focus through his writing, an analytical project that has thus far languished.

Already the picture of Marc’s reception is a massive, dense, and confusing one. As Marc’s historical legacy is built upon and diversifies, it is also necessarily transformed. Any definitive interpretation of Marc’s intentions through his writing may lead to wrong conclusions not through confirmation bias or lack of effort but from a failure to acknowledge the speciousness of putting too much stock in what Marc has to say to literalness.iv Studying Marc’s writings and biography invites the ignition of imagination, not in the sense of projecting capricious fantasies but in making a concerted effort to learn about Marc, and using that information to conceive of both the interpretation of the his work and words and the mise en scène around their making.

To accomplish this task, we must accept going in that Marc himself was very suspicious, intellectually and emotionally, of “meaning” in the way historians think of it today, and also as an arbiter of definitiveness in his own time.v Absolutism for Marc has aggressive, positivist, fascist associations which thwart at every level the act of contemplation.vi It can be very difficult to keep something as seemingly straightforward as writing in the intentional structure of non-meaning. But to do otherwise results in a quick grasp for transcendental signifiers. To leave “meaning” open and inappropriable is unsatisfying, frustrating, and completely necessary. A politics of refusing gratification through chronic indirectness in behavior and words is at the core of Marc’s practice, though this is not to say that he did not produce plenty of flat declarations and seemingly straightforward information to sift through – he did, and part of our process will be to examine Marc’s writings and the painting itself, in a quest not for the absolute but to consider clues which provide a launching point for imaginative possibilities.

The point of engaging in this activity, beyond investigating Marc, is also to learn how to activate the imagination, both morally and as a practicable ability that may be refined and improved, and to create quiet artistic projects which have no tangible form, and are therefore removed – in privacy and limitlessness – from consideration as physical, material products. In a larger observation about the nature of imagination as filtered through the tradition of German philosophy that was certainly known to Marc, Dee Reynolds makes the claim:

.The … sublime is … is opposed to the formal harmony of the beautiful, and its pleasure is a paradoxical one, inseparable from the pain experienced through the failure of imagination to achieve its goal. … [I]magination is overwhelmed by the ‘excess’ of a sensory object, and is unable to perform its synthetic function and grasp the object as a totality.vii

Marc helps us stake out a different position. The development of imagination, and its relative, empathy, can require patience and practice (and a sort of basis not in accuracy but in ethics)viii but it is not an activity that can be failed, just as an object need not be totalizingly possessed at all, cognitively or in any other way, to appreciate it. Instead the effort itself is potentially rewarding and beneficial. It is important to recognize that failure is not an outcome for imagination; even complete lack of “success” provides a lesson in humility and one that is easily recalled and inhered. In terms of identification with other living things – what Marc uses the term Sicheinfühlen to describe – many ethologists believe that a type of focused imagining about differences between species can play a role in moral education and development as concerns them.ix Loss of certainty beholding curbs arrogance: In considering how challenging it is to understand someone’s writing we are more likely to appreciate just how difficult it is to understand the person as a living being. We are less likely to arrogantly and prematurely conclude that we “understand” other people, or they us. In fact exposing the fault between our fantasies about the sublime and the spikier realities of considering the intersection of the immaterial with the realm of embodied vision and absorbed emotion can mean parting with an old way of thinking for one with more freewheeling rhythms and richer opportunities for the romance of creativity itself.

Franz Marc’s writings bear obvious, as well as concealed, signs of the times and the circumstances in which he worked. A good deal of his writing was of an occasional nature – reviews, journal articles, book chapters, lists, proposals, and letters – and seems to be something he just wanted to do as much for a source of auxiliary self-expression as to win collegial respectability and convince a wider audience of the benefits of advanced artistic receptivity.x Marc proved himself adept at expressing concerns that seemed to be his own in a manner that suited the occasion and, to a degree, the audience. This was allied with his preference for exploring his own ideas through the analysis of the works of others – Marc ascribes attributes to El Greco, Cézanne, even Lorenzo Ghiberti – which are actually modal and particular to himself.xi Marc’s aptitude for shorter prose forms – aphorisms, letters, reviews, essays – best suited to his own literary style has for us as its complement the intimation of a larger whole, a context never achieved. Today the most immediate context for Marc’s sometimes carefully, sometimes awkwardly-crafted fragmentary writings is that of his own life, and fate. But we should be wary of pre-judging (particularly since we are so committed to the perspective of hindsight) these possibilities as they presented themselves to Marc. Satisfaction in open-endedness was both an article of faith for Marc and a guiding principle of the open and experimental way in which he conducted his painting practice and his writing. It obscures, because it so well-complements, the effects of circumstances – depression, isolation, misunderstandings and animosities, war – on the overall shape of his work.

Yet all of these variables were present in Marc’s life. This can be gleaned from his writing, but mostly this conclusion is based on a reconstruction of Marc’s biography through both deductive logic and intuition. Going forward it will be important to reject forthwith sweeping generalizations such as Barbara Eschenburg’s statement that “Franz Marc expressed his ideas at length, both publicly and in letters, so we are well informed about his thinking…”xii In fact we are only informed about his writing, which is not the same thing as knowing someone’s thoughts, and not even very well-informed about the writing! Closely examining Marc’s words reveals an attachment to vagueness, and many inconsistencies;xiii this makes it less than difficult to purpose one passage or period toward one idea or another.xiv

Understanding Marc is often impeded in scholarship by the same type of historical omission of indicative personal details; in any case we should be willing to imagine what might have been going on to better grasp what it is possible to know. Conventional accounts depict Marc as a driven workaholic, though Marc was acutely opposed to nonstop art-making.xv It is true that the period from 1910 to 1914, in particular, is remarkable for Marc’s painting and writing output (and that of his circle in general). Yet oftentimes Marc was not particularly productive,xvi just occupied, and his life was never given over totally to dwelling on painting or writing, either his own or that of others. Marc’s periodic absorption in philosophical and moralizing literature – like that of Novalis, Goethe, Tolstoy, or Flaubert – with whom his identification was intense but oblique and, to an extent, channeled through the outlet of painting they did not possess, was another factor which encouraged the inconsistency of so much of his written work. The dutiful completion of his 100 Aphorismen (1915) – the only singularly-authored book to have achieved final form – may only have been possible because of the combination of external contingencies (the alternating peril and dullness of the war) and the fact that its governing paradigm had already been preceded by Nietszche.xvii

Thinking about Marc’s writing as a Teutonic spiral, at the center, I suppose, stands the brooding figure of Goethe,xvii but Marc’s attempt to distill a manageable marriage of Romanticism and Modernism achieves a satisfying resolution only in his painting. In verbiage, generally, it is as if Marc needed a certain indirectness, a detour via the intellect and experience of others, of the artwork he analyzes, in order even to face or to uncover his closest concerns – except that of his central and abiding concern, the representation of animal essences. Protecting his truest interest by the assumption that understanding animals might be a form of understanding best elided in language, Marc pursued this passion only in painting.

The preoccupations we share with Marc are one source of the difficulty we are presented with in approaching his writings. Marc’s dense, occluded principles of interpretation and expression are another. Marc’s “thoughts” instruct and mislead, but more importantly, they are simply not available, at least not in pure and integral form. Attempts to utilize Marc’s own words in understanding Marc historically are always in danger of lapsing into Marc-isms,xix and that, even with acute and aware perspectives, is simply not sufficient as a methodology because of the clearly inaccurate and incomplete results it yields. The scope of Marc’s influence is large enough, yet the variety of contexts into which he can be translated make the task of re-constructing Marc’s own texts one fraught with the dangers of misplaced emphasis, and misleading enthusiasm.xx It is impossible to ignore the fate, the after-life (which is after all for an artist the real life) of Marc’s biography and to focus simply on the writing itself. But even if present needs and intentions are the starting-point, and the myriad paths of Marc’s “influence” provide a map of approaches rife with dead ends, there is much to be said for making an understanding of Marc’s writings themselves, in their difficult and often frustrating production, the partial aim of our efforts.

Closely studying Marc’s writing is important to gain an understanding of Marc as a person, inasmuch as this can ever be possible, which means aggregating enough information that by analyzing the data available, incorporating it into a sort of biographical timeline, and using a particular strategy of deductive, intuitive identification (sichhineinfühlen)xxi it becomes possible to occupy briefly an imaginative threshold that gives insight if not absolute answers into how Marc might have actually felt about the major thrust of his creative life, the animal paintings, and how they related to his real relationships with flesh and blood animals, and people. Of course imaginatively inhabiting someone’s personality is far more difficult task than simply assembling a mass of facts about the person.

Marc was an inveterate letter- and postcard- writer, and though he was perhaps conscious of the preservation aspect of his later correspondence,xxii the medium seemed to fill a need, not for mere communication or historicity, but for some larger exercise of emotionalism and imagination, in his typically animated reaction to stimuli which also found an outlet in a considerable amount of physical activity and travel. Many of the letters also seem to have been provoked by all the myriad practical complications of which Marc’s life was so full.xxiii

Yet for all their effusiveness Marc’s letters also show us a person of great reserve; even where he lets himself go with people he loves and trusts – as in the very entertaining report to August Macke about a confrontation with Gabriele Münterxxiv and his fretful letters to Maria Franck during their periods of separation – you get the feeling not of the revelation of some true inner self but merely of the relaxation of that reserve. Marc adopted for his public writing persona an extraordinarily stolid manner; a sort of reverse sprezzatura that makes a pointed stylistic comment through its stuffiness on the artistic tastes and superfluous materialistic rituals of the class whose superficiality he was devoted to undermining, including attacking the easy artificiality of the artists who “seceded” from it.xxv

Marc’s peculiar “execution of the author” may ironically account for the difficult fascination Marc has had for historians – using the collected letters of Vincent Van Gogh as comparisonxxvi – by not giving the interests and commitments of the absent subject of Marc’s personality the kind of scrutiny normally due a flesh-and-blood being of historical interest and import. xxvii Marc’s conventional and easily quantifiable pursuits, such as book collecting, are thereby cemented in advance as canonical relics, and his well-known maxims on color theory, abstraction, and particularly some of his correspondence from the field are repurposed frequently, wrongly, and out of the context of their production, while it is Marc’s more arcane preoccupations with animals – such as keeping a herd of deer and the scores of references to his closest companion, his dog Russi – are glossed in the telling. Marc’s more personal notes – the Paris-based correspondence from 1907, for example, in which traces of a passionate agitation are preservedxxvii – are only a little more revealing. The distinction between what this genre of writing lightly fictionalizes and what it reports clearly is beguilingly blurry.

Concurrent with the production of the Almanac, Marc also assumed a self-conscious oratorical tone for his public journalism pieces, including those that appear in Der Sturmxxix and PAN.xxx This public persona nonetheless generates some useful text and subtext for sussing out Marc’s unstated concerns. “Romantic Expressionism” is a good way to describe Marc’s essays in 1911 and 1912, which betray his penchant for prelapsarian longing despite their agitation for the new era.xxxi Some notion of looking back was even in Marc’s first Paris diaries from 1904, its notations about the ritualized trips to bakeries and markets recalling family and childhood. xxxiiMuch later, about Paul Lasker, the young son of Else Lasker–Schüler, Marc says: “…There is something in his face which touches me and my childhood memories and secrets and which I love in him.”xxxiiii

During 1910 and 1911, Marc spent a lot of time traveling, visiting, and socializing with art dealers, publishers, other artists, and an assortment of people not exactly known for circumspect behavior, and some of the correspondence with August Macke alludes to various types of debauchery.xxxiv Yet for all his exposure to hedonism, not just in Paris but later in Dresden and Berlin, Marc is, on the page, quite the moralist.xxxv

Marc’s own texts and the constellar correspondences with family and friends are by no means the only source through which his ideas have come down to us as distillations. After his death, several of his acquaintances produced and published books on themes and utilizing insights which belonged to the complex of nexus of subjects and processes which interested him.xxxvi Paul Klee, despite his very canny and carefully-worded memoriam about Marc, in particular seemed to continue to dwell on his sometime friend, finally, later in life shedding his fondness for detached and even humorous distancing for something that approximated Marc’s own solemnity.xxxvii

One thing Marc was quite well-aware of was the existence of a German-language readership that was, if not per force receptive to Marc, quite accustomed to being lectured to about what type of art, literature, and music it was supposed to like.xxxviii During the age of the feuilleton critics and cultural commentators in journals and newspapers could claim to form and inflect public taste and debate. In an enterprise characterized chiefly by drive, Marc was able to penetrate, through his persistent freelance submissions and his enthusiasm for personal networking, a subculture organized around books and journals and inhabited by literary intellectuals whose domain was not paint but print. Did Marc wish to be such a public intellectual in this sense? It does seem to be part of what he aims for in his essays though he does not cast himself in postmodern terms as a “writer slash painter” concerned about a choice between being an artist or a writer who advocated for art.xxxix In Marc’s writing, the choice was between materialism and spirituality, nationalism or cosmopolitanism, stifling naturalism or the connections new painting offered between the past and the coming spiritual epoch.xl Though he was undoubtedly greatly inspired by both Kandinsky’s and Wilhelm Worringer’s xli writing, Marc’s reviews for PAN and Der Sturm are best seen not as an attempt to achieve a similar theoretical imprimatur but to frame a cultural debate with political ramifications and to do so by whatever public platform was available; this seems in keeping with Marc’s adherence to fundamentally representational paintings.xliii Marc expects that people who grow up looking at advanced art will understand its language from childhood and thereafter – but he doesn’t give instructions for how exactly to experience his own paintings, it would seem for the reason of not wanting to pin them down to singular interpretations.

The majority of Marc’s published correspondence in German is known through the volumes of letters edited by Klaus Lankheit,xliii whose priority is admiration, and contains for the most part exchanges with Maria Marc, and Kandinsky and Macke (who had little in common save their jealously-guarded friendship with Marc, which was for supremely precious to each of them, albeit in different ways). Marc himself seems to have regarded the sort of rivalries and contretemps he inspired with concern and attempts at mitigation.xliv

The volumes of letters show glimpses of Marc’s very intense relationship with Mackexlv and the more intellectual exchanges with Kandinsky (they never once said du to each other). What is notably missing is Marc asking for, or getting, any type of response from Kandinsky about Marc’s paintings (Kandinsky’s self-recriminating and personal, defensive, critical responses to various Marc letters, and above all to the Almanac materials and cover drawing do nothing to illuminate Marc). Such exchanges can also be seen as a way of confirming what Kandinsky clearly considered at the time their narrower alliance against the outside world – “unser seltenes Verhältnis”, as he calls it, asking “Oder sollen wir unter dem Druck des ›Bösen‹ alle weiter leiden?”.xlvi But Kandinsky seems more anxious to seal this pact than Marc, whose replies often reflect oblique compliance, continued curiosity about what is going on in European painting both geographically and in a larger theoretical context, and his different assortment of alliances and friends.xlvii

The volume of Marc writings translated by Thomas de Kayser and annotated by Maria Stavrinaki is very satisfying and splendidly edited and annotated in Gallicisms it seems like Marc would have appreciated.xlviii De Kayser sets aside one particularly telling episode in the general Vinnen protest saga – “La polémique entre Marc et Beckmann” which devolves into some ad hominem attacks of which it cannot be said Marc does actually get the better end.xlix However the “Anti-Beckmann” essay does allow Marc, after dismissing Beckmann’s points on facturel and national interest with a sort of sweeping “Cézanne, Gauguin, whatever!” declamation and lamenting the tenor of the exchange, to say something quite interesting, in effect that he thinks it is more important to have better good, new, imaginative ideas for new painting than to be an excellent but conventional renderer.li

The Beckmann situation is also a way to investigate the matter of Marc’s political commitment,lii which, like all deeply but quietly formed ideological choices, must be grasped on a number of levels at once: painting as a form of personal revolt; the emerging spiritualized mentality as a new kind of universalism in which painting could fully exert and influence on greater issues of religion and morality; thinly-concealed loathing for the bourgeois – his own – class, and an identification with those of radically different backgrounds, including different species. The appeal of this sort of leveling effect of “justice through art appreciation” ought not to be dismissed as some figment of misguided Nietzscheanism, either for, as Oscar Wilde put it, aesthetic socialism precludes the necessity for people to “spoil their lives by an unhealthy and exaggerated altruism.”liii Marc’s behavior indicates, ultimately, that he wishes to secede from organizations and groups altogether and to identify – to share experiences – with rural populations and with animals – and shortly after the Beckmann fracas, in early 1912, instead of capitalizing on what otherwise could have continued as a delicious rivalry with his self-declared nemesis, he does this, abandoning his Munich studio and retreating to remote farms first in Sindelsdorf and then Ried.liv For us as Marc detectives, such identifications are certainly to be welcomed inasmuch as they enlarge our sympathies and undermine or dissolve the confines not just of what we suppose about Marc, the Munich personality, but of our own class limits and appetites for conflict, and provide evidence through action of what Marc may truly have been thinking – that true creatives want to create, and their deeper, more unguarded reflections bounce off the obstacles a system places in the way of those vocations.

For Marc scholars, the Paris journal from 1903, and the later letters from 1907-1908, are fragmentary but vague, offering Marc’s notes on travels and places and sometimes people, much less on his own reading and projects.lv It is possible to read the annotated Écrits almost as a novel, reconstructing the biographical narrative and re-inventing the various characters at varying distances from the charismatic central figure himself. The important thing for us to remember is that these letters in no way correspond to the circumstances under which they appeared or were written. Marc writes in a somewhat tormented way that nonetheless prods associative leaps that can be grasped either as the intensity of Marc’s own projective process or as a protective multi-layering.

More than a decade later, close to the end of his life, Marc continued to mistrust the absolutism of language:

One should not rely too much on words; there is nothing more changeable than words. On every human level, in every environment, they always mean something different. People speculate with words just as they do with securities. How can one use such a vulgar tool to tell the truth! The ordinary human being uses language for totally improper things which cause confusion. One should talk much less, and live only by emotion.lvi

Given then that finally Marc seems to have little faith in writing, and gives almost no information precisely about how to take his animal paintings, what, then, is the purpose in studying Marc through his writing? The answer is precisely that words whose place is at present eclipsed by the au courant urgent need for a definitive interpretation are in need of better lighting. I say “at present” because the current academic epoch, which makes so many things impossible because of its insistence on “the argument,” most certainly does not preclude this: That in the passage of time, the right light might fall precisely on our reconstructions of Marc’s life and words. One reason for being persistent in our excavations and reinterpretations of Marc’s writing is that these efforts can, in their small way, be astronomical measuring instruments, which, if they function well, will measure the tiniest segments of that shifting shadow.

To properly and morally imagine and reconstruct, we must try to conceive not just of the past itself and Marc’s drives and energies, but rather the distance separating what is currently in shadow from some fuller natural light. So we have constantly to be aware of the magnitude of our “unknowledge.” This means we have no privileged understanding; that full empathetic immersion in Marc’s relationships with Russi, with his family and friends, and with the legacy of Goethe and Flaubert are not possible for us today. The holdover Romantic ideas invoked by Marc in his correspondence, the emphasis on unity and a certain dogged hopefulnesslvii no longer seems to resonate in a postmodernity which has abolished those things. Yet there is no doubt that for a few brief years Marc was part of a true intellectual avant garde, the equals of the great artistic or literary movements, whose passion for the spiritual in art can no longer be duplicated. Yet historical elaboration need not take the form of imitation.

Occupying the enterprise of Marc’s creative life takes shape as something intrinsically incomplete. Instead of a life’s work, or a life of work, Marc left a life’s commitment to writing, painting, criticism, and experiment, and the inspiration of such in others.

Bibliography

Butt, Gavin. Between You and Me : Queer Disclosures in the New York Art World, 1948-1963. Queer Disclosures in the New York Art World, 1948-1963. Durham: Duke University Press, 2005.

Dilthey, Wilhelm. Das Erlebnis Und Die Dichtung : Lessing, Goethe, Novalis, Holderlin. Leipzig: Leipzig : Teubner, 1910.

Eschenburg, Barbara. “Animals in Franz Marc’s World View and Pictures.” In Franz Marc: The Retrospective, eds. Annegret Hoberg and Helmut Friedel, 51-71. Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2005.

Fellenz, Marc R. The Moral Menagerie: Philosophy and Animal Rights. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007.

Franciscono, Marcel. Paul Klee: His Work and Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Gutschow, Kai Konstanty. “The Culture of Criticism: Adolf Behne and the Development of Modern Architecture in Germany, 1910-1914.” PhD diss., Columbia University, 2005.

Kandinsky, Wassily, and Franz Marc. The Blaue Reiter Almanac. Boston: MFA Publications, 2005.

——— Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter, Maria Marc, and Klaus Lankheit. Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Briefwechsel,: mit Briefen von und an Gabriele Münter und Maria Marc, München: Piper, 1983.

Klee, Paul. The Diaries of Paul Klee, 1898-1918. edited by Felix Klee Berkeley: Berkeley, University of California Press, 1968.

Lankheit, Klaus. Franz Marc: Sein Leben und Seine Kunst. Ko¨ln: DuMont, 1976.

Lasko, Peter. The Expressionist Roots of Modernism. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003.

Macke, August and Franz Marc. August Macke, Franz Marc; Briefwechsel. Ko¨ln: DuMont, 1964.

Marc, Franz. “Die konstruktiven Ideen der neuen Malerei.” Pan 2, no 18 (March 21, 1912): 527–531.

——— Briefe, Aufzeichnungen und Aphorismen. Berlin: P. Cassirer, 1920.

——— Briefwechsel: Mit Briefen Von Und an Gabriele Münter Und Maria Marc. Munich: R. Piper, 1983.

——— Écrits et correspondances. Paris: École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, 2006.

——— Franz Marc: Letters from the War. Eds. Klaus Lankheit and Uwe Steffen, trans. Liselotte Dieckmann. New York: Lang, 1992.

——— Postcards to Prince Jussuf. ed. Peter-Klaus Schuster, Munich: Prestel, 1988.

——— Schriften. Köln: DuMont, 1978.

Morgan, David. “Concepts of Abstraction in German Art Theory, 1750-1914.” PhD diss., University of Chicago, 1990.

Pollock, Mary Sanders and Catherine Rainwater. Figuring Animals: Essays on Animal Images in Art, Literature, Philosophy, and Popular CultureSymbolist Aesthetics and Early Abstract Art: Sites of Imaginary Space. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Short, Christopher. The Art Theory of Wassily Kandinsky, 1909-1928: The Quest for Synthesis. New York: Peter Lang, 2010.

Van Gogh, Vincent. “Vincent van Gogh’s Letters.” The Van Gogh Museum. DOI 18 June 2014. www.vangoghletters.org.

Walton, Kendall L. Mimesis As Make-Believe: On the Foundations of the Representational Arts. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990.

Wilde, Oscar. The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, eds. Russell Jackson, and Ian Small. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

__________________________________________________________

i Hans Tietze noted the historical ramifications of the Almanac in an initial review of the book and throughout his career. Hans Tietze, Die Methode der Kunstgeschichte; ein Versuch. (New York: B. Franklin, 1973.)

ii Marc’s written works remain largely untranslated and unknown to Anglophone scholars, a situation which has motivated me to increase Anglophone knowledge of Marc’s fascinating textual life.

iii Kai Konstanty Gutschow, “The Culture of Criticism: Adolf Behne and the Development of Modern Architecture in Germany, 1910-1914.” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 2005). In his dissertation on art and architecture critic Adolf Behne, Gutschow provides a substantive background on the importance of the Blaue Reiter artists attached to their writing as a means of helping a sometimes unreceptive public better understand their images.

iv Franz Marc, Franz Marc: Letters from the War, eds. Klaus Lankheit and Uwe Steffen, trans. Liselotte Dieckmann, (New York: Lang, 1992) 92. “One must always remain conscious of the limits beyond which the word no longer means anything and falls back on its stupid grammatical sense,” Marc writes in a letter from 14 January 1915.

v Franz Marc, Franz Marc: Briefe, Schriften, Aufzeichnungen; (Leipzig: Gustav Kiepenheuer, 1989), 94. “Sicher verstehen wir uns in der bewußten Frage nicht ganz richtig. Denn wenn ich Ihren Gedanken annehmen soll, dann wird doch alles vollkommen, was überhaupt wird, und die Sehnsucht nach Vollkommenheit, nach einer höheren, vollkommeneren Seinsform stirbt ab. Unsere Kunst, Musik ist Nekromantik, maniera divina, niemals etwas Positives. Und daneben hab ich noch das Gefühl: stets voll Schlacken, erdunrein, – hier unterscheiden wir aber ein Mehr oder Weniger von Reinheit. So erscheint mir Picasso reiner als die anderen Kubisten, Fiesole reiner als Botticelli. Ich glaube, unsre Gedanken darüber laufen hübsch nebeneinander, was der eine fallen läßt, nimmt der andere auf ….” In this letter, following lengthy exchanges about problems – mostly personality-related – to both the design of the Blaue Reiter Almanac and the attendant exhibitions, Marc is still not willing to make the project a closed circuit and these types of misgivings appear frequently in these personal sorts of letters meant to distance and clarify as well as soothe.

vi “Kandinskys Bilder dagegen sehe ich in meiner Vorstellung ganz abseits der Straße in die blaue Himmelswand getaucht; dort leben sie in Stille ihr Feierleben. Sie sind heute noch da und werden bald ins Dunkle der Zeitenstille entweichen und strahlend wiederkommen wie Kometen. Wenn ich an diese Bilder denke und zugleich an das, was der Europäer ›Malerei‹ zu nennen sich gewöhnt hat, so habe ich ein Bild in meiner Vorstellung, wie der ›Geist‹ die Malerei heimsucht; ja und schwer heimsucht! Sie hatte sich so wohl ohne ihn gefühlt und ist nun höchst erschrocken und schlägt verzweifelt um sich, um den ›Geist‹ nicht eindringen zu lassen. Das müßte Paul Klee zeichnen. Nur er könnte das. Franz Marc, “Kandinsky,” Der Sturm, 4, Nr. 186/187, November 1913, pp. 130.

vii Dee Reynolds, Symbolist Aesthetics and Early Abstract Art: Sites of Imaginary Space, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 10-11. Reynolds ideas certainly have some traction in a general consideration of embodiment and imagination and seem particularly well-suited for a discussion of Modernism and dance, which is her project now. However in the interest of examining what is specific to Marc, it is important to note how removed Marc’s work is from the type of Symbolist aesthetics and tenets Reynolds uses as bellwethers in this book. In fact as Reynolds refers to French Symbolism – as a sort of late manifestation of German Romanticism – it is more reasonable to observe that Marc completely “jumps over” Symbolism – in the way Novalis frequently invokes this notion – and more directly links Romanticism and modernism.

viii Kendall L. Walton, Mimesis As Make-Believe: On the Foundations of the Representational Arts, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990), 99-103. The study of animal behavior is of course relevant to Marc’s goal of “feeling into” animals. Walton links the moral imagination with ideas about standpoint epistemology originating with Karl Marx, and draws attention to relations of power and the special difficulties that those in power have in trying to understand the world from the point of view of those without power. Walton’s points are obviously useful to consider in thinking about animals issues, but also offer persuasive political reasons to develop powers of empathy and imagination with the intent to use these abilities morally.

ix For more on how the ethical imagination vectored through the visual arts relates to contemporary animal rights issues, see Mary Sanders Pollock and Catherine Rainwater, Figuring Animals: Essays on Animal Images in Art, Literature, Philosophy, and Popular Culture, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005) and Marc R. Fellenz, The Moral Menagerie: Philosophy and Animal Rights, (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007). The authors of these essays and studies generally agree that simply being able to envision animals as conscious, capable of experiencing cognition but above all suffering, is an essential motivation in improving the lot of the nonhuman animal.

x Franz Marc, Franz Marc: Schriften; (Köln: DuMont, 1978), 101. Marc sometimes has a quite limited definition of “public” even at his broadest range, including only members of the German arts circle, and not even all of them, as he observes in this September 1910 piece pre-emptively defending the NKVM show at the Thannhauser Gallery: “An etwas stößt sich hier das Publikum augenscheinlich: es sucht Staffeleikunst und wird nervös und zweiflerisch, wenn es kaum ein reines Staffeleibild von gewohntem Stil in dieser Ausstellung findet. Bei allen Bildern ist noch ein Plus im Spiel, das ihm die reine Freude nimmt, aber jedesmal den Hauptwert des Werkes ausmacht. [Die Bilder sind als Exempel gemalt für weite Ideen über Raumaufteilung und dekorative Farbenwerte, die sich einst das kommende Kunstgewerbe nutzbar machen wird. Die meisten dieser Bilder müssen mißverstanden werden, wenn man diese Voraussetzung außer Acht läßt. Aber kann sie nicht als Mahnung dienen, diese Künstler mit dem Ernst anzusehen, den sie verdienen? –]”

xi “Diese melancholische Betrachtung gehört insoweit in die Spalten des ›Blauen Reiters‹, als sie ein Symptom eines großen Übels zeigt, an dem der› Blaue Reiter‹ vielleicht sterben wird: die allgemeine Interesselosigkeit der Menschen für neue geistige Güter.

“Aber vielleicht behalten auch wir recht. Man wird nicht wollen, aber man wird müssen. Denn wir haben das Bewußtsein, daß unsere Ideenwelt kein Kartenhaus ist, mit dem wir spielen, sondern Elemente einer Bewegung in sich schließt, deren Schwingungen heute auf der ganzen Welt zu fühlen sind.

“Das Bild von Picasso, das wir nebenstehend bringen, gehört, wie die Mehrzahl unserer Illustrationen, in diese Ideenreihe.” [Originally from “Geistige Güter” (October 1911) in: Der Blaue Reiter, München: Piper, 1912] Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc; The Blue Rider Almanac, (Boston: MFA Publications, 2005), 1-4.

xii Eschenburg, “Animals in Franz Marc’s World View and Pictures,” 51.

xiii Marc was familiar with the Swiss feuilleton and short story writer and novelist Robert Walser, and knew Walser’s work through Paul Klee, and because it appeared often in German newspapers and art journals. It is actually Walser’s defiantly opaque aphorisms that Marc’s public writing persona closely echo. Klee’s interest in Walser and the connection to Marc discussed broadly in Paul Klee, The Diaries of Paul Klee, 1898-1918, ed. Felix Klee (Berkeley: Berkeley, University of California Press, 1968).

xiv Eschenburg, “Animals in Franz Marc’s World View and Pictures,” 65. Some recent interdisciplinary scholarship proposes that it is useful, in terms of developing trans-era empathy, to contextualize artists’ writing less selectively, employing interpretive biography but also considering the writing that is not there; for example, in Between You and Me: Queer Disclosures in the New York Art World 1948-1963, Gavin Butt describes in detail the fraught and complicated relationship amid Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns, and how the cumulative effect of an unwritten demimonde of, basically, gossip, reached a denouement in Johns’s Target with Plaster Casts (1955). Butt’s point (amid others in this compelling study) is that examining the reviews of the day are revealing precisely because of what they omit in discussing Johns’s work. Gavin Butt, Between You and Me : Queer Disclosures in the New York Art World, 1948-1963, Queer Disclosures in the New York Art World, 1948-1963 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005).

xv Marc, Briefe, 29-30, letter to August Macke of May 1910: “Ich bin hier sehr fleißig, an ein paar sehr großen und vielen kleineren Sachen. Ich stelle an meine Vorstellungskraft wieder die unverschämtesten Anforderungen und lasse alles andere, Theorie und Naturstudien, wie Sie’s verstehen, hinten.”

xvi Marc spent a lot of time between 1907 and 1910 working very slowly on just a few monumental size paintings some of which he did not complete or destroyed, owing, it seems, to being defeatingly depressed. Marc continues to be periodically burdened by the inability to concentrate: “Real activity is completely missing for me, except for rare days. I am not physically damaged, I am just speaking of my very ordinary nervous mood which keeps me from work,” he writes in a letter to Maria Franck from 1914 (Franz Marc, Letters from the War, 19.) In better times, some of the things that Marc seems to be very good and comfortable at doing is just spending a good deal of time napping, socializing, wandering around and mulling over ideas.

xvii David Morgan, “Concepts of Abstraction in German Art Theory, 1750-1914,” (PhD diss., University of Chicago, 1991), 172. Morgan in fact points out that the dominant theme of the Aphorismen was “the discovery that even the laws of science are mental constructions and that reality is a recession of ‘faces’ which are successively penetrated.” Marc was of course very familiar with the work of Friedrich Nietszche, who often employed the aphorism, as discusses and exemplified in: Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, The Case of Wagner ; Nietzsche Contra Wagner; Selected Aphorisms, (Edinburgh: Foulis, 1911).

xviii For an explanation of what about Goethe’s “Essay on the Theory of Painting” would have appealed to Marc, see: Christopher Short, The Art Theory of Wassily Kandinsky, 1909-1928: The Quest for Synthesis, (New York: Peter Lang, 2010).

xix Marc tends greatly to announce fresh outrages or points of indignation with rhetorical questions to the effect of “Isn’t that incredible?” or “Can you believe this?” which have, at least retroactively, an effect both signatory and amusing. See Briefe, Schriften, and the essays in the Blaue Reiter Almanac.

xx Eschenburg, “Animals in Franz Marc’s World View and Pictures,” 70-71. With regard to a fascination with particle physics, it is probably more accurate to say that Marc was interested in the nascent discovery of the atom, as any educated person of the time would be. This seems like a minor point but it is actually an important distinction to make in interpreting Marc’s beliefs and philosophies. His comments about the concealment of realities by various surfaces and mirages are about something else entirely; about encouraging Sicheinfühlen as a methodical process for imagining the essences of others. Marc was not a positivist, materialist new-age flake who proposed that just thinking hard enough about “energy waves” would produce some sort of actual change in the physical world. He does not seem to have believed anything like this at all. Much license has been taken with Marc’s writing and painting over the years in many genres of culture.

xxi Marc, Briefe, 31. Marc uses this word in his oft-quoted letter to Reinhard Piper about Marc’s general intention to depict “the inner lives of animals;” what he seems to mean (keeping in mind Marc’s tendency to sort of over-explain facts to Piper) beyond simply “identification” with animals is something closer to actually sharing experiences and ideas with them; this is what we have to try to do with Marc.

xxii Marc was a terrible record keeper which is one of the reasons it has been difficult to assess the papers and notes in his estate, however, he did make a point to indicate to his friend Else Lasker-Schüler that the postcards he wrote to her were to be inherited by or sold for the benefit of her son, Paul Lasker, of whom Marc was quite fond. Noted by the editor in Franz Marc, Postcards to Prince Jussuf, ed. Peter-Klaus Schuster, (Munich: Prestel, 1988).

xxiii A lot of Marc’s problems came about as a result of his own awkwardness and impetuous judgment, such as the process of procuring his divorce. Much of Marc’s correspondence with Kandinsky is impelled by the concurrent Blaue Reiter exhibitions and publications.

xxiv August Macke and Franz Marc, August Macke, Franz Marc; Briefwechsel, (Cologne: DuMont, 1964), 113. Letter of 28 March 1912: “Jetzt ist er schon hin! Viel fehlt wenigstens nimmer. Jedenfalls hat dieses Frauen ziefer auf meine Freude am Blauen Reiter bös gespuckt. Kandinsky leugnet vollkommen, dass Meinungsverschiedenheiten zwischen ihm und mir irgendwie in Betracht kamen; lediglich ganz personlich gekrankte Eitelkeit von Munter, die ich, wie sie und (hinter ihr verschanzt) er sagt, wie einen Stuhl behandele.

Stell Dir vor, dass sie mir in’s Gesicht vorwirft, ich hatte dann und dann auf der Strasse oder am Kaffee-eingang nicht den Vortritt gelassen, hätte sie vor ca. zwei Monaten einmal auf eine Bemerkung von ihr unwirsch angeblickt oder ein andermal eine Einsprache ihrer-seits unbeachtet gelassen usw. Ich übertreibe nicht; es ist zum Kaputtlachen, wie Du sagst, aber für mich auch sehr traurig um Kandinskys willen, den ich sehr liebe und dessen Verkehr, mir teuer war.

Er wurde von ihr als Posten aufgestellt, meinem Benehmen zu ihr aufzulauern und bestatigte als Pantoffelheld die ‘Berechtigung’ ihrer Vorwürfe!! Er behauptet zwar, dass ich auch gegen ihn kühler geworden sei; als ich nach der Begrundung frug, konstatierte Munter, dass ich kurzlich sein neues Bild, das auf der Staffelei gestanden, gar nicht angesehen hatte; das ist wahr; ich war kurz dort, hundsmüd, wir hatten wegen dem Blauen Reiter einen Haufen zu bereden, und ich hatte keine Lust, mir Bilder anzusehen. Das Ganze ist so dumm, dass man sich schamt, es niederzuschreiben. Und dann der Fall August!!!”

xxv Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, >em>The Blaue Reiter Almanac, (Boston: MFA Publications, 2005), 64. “Not all the official ‘savages’ in or out of Germany dream of this kind of art and of these high aims. All the worse for them. After easy successes they will perish from their own superficiality despite all their programs, cubist and otherwise.”

xxvi Van Gogh’s correspondence with his family and with other artists has been published on multilingual platforms for a long time, culminating recently in the Van Gogh Museum’s Website, vangoghletters.org. The availability of Van Gogh’s writing, and its subsequent scrutiny by many people from all disciplines, make it clear that there is no singular interpretation of Van Gogh’s oeuvre. The availability of such data also makes ascertainment of the type of historical facts possible – some researchers from the Netherlands recently compared Van Gogh’s letters about the composition of

xxvii Annegret Hoberg by virtue of her position as curator at the Lenbachhaus with access to and familiarity with the collected paper archives related to Marc is a great source of biographical data about Marc. Yet in her various books and lectures Hoberg flatly states she has no interest in assessing the effect of Marc’s personal complications upon his work, perhaps a naturally protective tendency but an historically risky strategy, if the purpose of holding such an archive is to be able to study, not beatify, Marc. Annegret Hoberg and Isabelle Jansen, Franz Marc: The Complete Works, Volume 1, (London: Philip Wilson, 2004).

xxviii Germanisches Nationalmuseum, (correspondence with Friedrich Lauer about problems encountered during their 1904 trip to Paris). Marc apparently had a romantic relationship with a French teenager and was subsequently blackmailed by the teen’s family.

xxix Franz Marc, “Zur Sache,” in Schriften, 134. “Aber auf eine Sache lohnt es sich, nochmals den Finger zu legen: Ich schrieb: »Wir Maler schaffen nicht so sehr Bilder als Ideen« und schrieb diesen Satz mit gutem Bewußtsein. Warum nimmt man Anstoß an dieser Sache? Warum wird man beschworen, sie nicht zu sagen? Will man leugnen, daß unsre gegenwärtige Zeit unter diesem Zeichen der »neuen Ideen« steht? Wer unsre Zeit kennt und liebt, sieht hierin ihre Pracht und trunkene Schönheit. Nicht die einzelnen Bilder sind dem Gegenwartsmenschen Selbstzweck und Hauptsache, sondern die Ideen, der Ideenkomplex, den die einzelnen Werke bilden.”

xxx Franz Marc, “Die neue Malerei,” in Schriften, 101. “Der kluge Matisse umging die Gefahr, ein Charakter ähnlich wie Hodler. Die beiden beachten die Gewissensnot ihrer Zeit nicht, sondern zeigen ihr, wie sie schnell und einfach gesunden könnte. Sie sehen nicht weit in die Zukunft und unterschätzen den Charakter der Jungen, deren Weg heute steinig und schwer zu finden ist. Diese gingen auch nicht lange mit Matisse und Hodler, sondern scharten sich um Picasso, den Kubisten und logischen Exegeten Cézannes; denn in dessen zauberhaften Werken liegen la tent alle Ideen des Kubismus und der neuen Konstruktion, um welche die neue Welt ringt.”

xxxi Marc, Briefe, 27. Letter to Maria Franck from June, 1907: “… Ich male jetzt schon überhaupt nur mehr das allereinfachste; ich sehe auch gar nichts anderes in der Natur an. In mir lebt jetzt eine Stimme, die mir immerwährend sagt: zurück zur Natur, zum allereinfachsten; denn nur in dem liegt die Symbolik, das Pathos und das Geheimnisvolle in der Natur. Alles andere lenkt ab, verkleinert und verstimmt …”

xxxii Marc, Schriften, 81-90.

xxxiii Marc, Letters from the War, 90. This letter is from 5 December 1915.

xxxiv Macke and Marc had several drunken altercations – with each other – resulting in the destruction of several paintings and the cabinet of curiosity of Macke’s landord. August Macke, Margarethe Jochimsen, and Peter Dering, August Macke in Tegernsee, (Bonn: Der Verein, 1998), 38-39.

xxxv “Lest bitte heute vor dem Schlafengehen in der Bibel das Hohelied Salomonis, Kapitel 7 und betet, dass Ihr nicht in Anfechtung fallet,” Marc advises August Macke about spending too much time with Gabriele Münter. From Marc, Macke, Briefwechsel, 22-23.

xxxvi Klee and Kandinsky obviously continued to refer to Marc including during their collaboration at the Bauhaus, but Rainer Maria Rilke was also an admirer, as was Franz Kafka.

xxxvii Marcel Franciscono, Paul Klee: His Work and Thought, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 169-170. Klee continues to wonder about the discord between Marc’s belief system and behavior, reflecting upon Marc’s excessive interest in the 1910 Gerhart Hauptmann novel Der Narr in Christo Emmanuel Quint.

xxxviii Two excellent studies on the German arts publishing milieu and what was at stake intellectually and economically – the latter of which was of little interest to Marc – are: Robin Lenman, “Painters, Patronage and the Art Market in Germany, 1880-1914,” Past and Present, No. 123, May 1989 and Peter Paret’s The Berlin Secession: Modernism and Its Enemies in Imperial Germany (Harvard University Press/Belknap Press, 1980).

xxxix Maria Marc’s correspondence with Elisabeth Macke and Marc’s own more brief asides to Else Lasker-Schüler indicate generally that while the Marcs found the circles of writers, poets, and critics they visited in Berlin to be trenchant and witty, they were put off by the sometimes viciously competitive interpersonal strife. This subject comes up in the correspondence contained in Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Briefwechsel,: mit Briefen von und an Gabriele Münter und Maria, ed. Klaus Lankheit; (München: Piper, 1983).

xl Marc, “Two Pictures,” in The Blaue Reiter Almanac, 65-69.

xli Morgan, “Concepts of Abstraction,” 185. One of the difficulties in assessing Marc’s textual influences is that, as with people, books, and paintings, he likes everything the first time he is exposed to it. Still in terms of applied theory – how Marc considers space and sensation, and his connection to Gothic motifs and architecture – it seems like Worringer’s positions on the livingness of spatial perception hew more closely to what Marc does; Marc writes of his favorable impression of Worringer on numerous occasions, right up until his final letters from the war. Morgan gives the following argument about how it was Worringer rather that Theodor Lipps who more appealed to Marc: “It was against Lipps’ aesthetic of objectified self-enjoyment that Worringer reacted. … Worringer shifted the concept of presence at work from the self-affirmation of empathy to the self alienation of idealist transcendentalism. Marc’s repudiation of empathy and his search for an art form which eschewed anthropomorphism parallel Worringer’s notion. Marc sought to hear things speak for themselves, to visualize them as what they are independent of the conventions of naturalistic representation … Marc indulged in an Expressionist yearning to establish a complete triumph over conventionality or artifice.”

xlii Franz Marc, Écrits et correspondances, (Paris: École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, 2006), 156-157. The era of la nouvelle peinture will augur among other things, an evolved and receptive public, progressive museum collections, better critical reception of new work, and more congenial fellow artists.

xliii Lankheit devoted his life to beatifying Marc, resulting in an excellent biography (the only one ever published), Klaus Lankheit, Franz Marc : Sein Leben U. Seine Kunst (Ko¨ln: DuMont, 1976).

xliv Marc, Schriften, 66-67. “Daß sie ›unfertig‹ sind und nicht ganz ›gekonnt‹, das weiß ich; darum bat ich Dich auch um Dein offenes Urteil. Aber es wird mir schon einmal gelingen, es besser zu machen. Über etwas bin ich etwas böse: daß Du darüber nachdenkst, daß der Blaue Reiter Dich nicht reproduziert und daß ›Du nicht leicht dazu zu bewegen sein wirst, etwas dazu herzugeben‹. Du hast Dich im Herbst, als die Reproduktionen festgestellt wurden, strikt und formell dagegen gewehrt. Kandinsky sagte, er kann hier nicht eigentlich mitreden, da er ja gar nichts von Dir kannt.”

xlv See August Macke, August Macke, Franz Marc: Briefwechsel, ed. Franz Marc (Köln: M. DuMont Schauberg, 1964).

xlvi Kandinsky and Marc, Briefwechsel, 1983) 158.

xlvi Marc is close to his immediate family and had a lot of contact with people who have no direct affiliation with the world of painting, including his farm neighbors in Sindelsdorf and Ried who ended up helping out quite a bit with various animal care problems.

xlviii Franz Marc, Écrits et correspondances. Paris: École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, 2006.

xlix Ibid, 152-153. Beckmann does make the good point that some of les personnalités nouvelles – meaning the German ones, not the collection-penetrating French whose presence had begun the quarrel – had not actually been trained or bothered to learn to draw, and since Marc had, this must have been quite a trialsome insult.

l Peter Lasko, The Expressionist Roots of Modernism, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003), 88. Of course some art historians do not think Marc is a very good artist. Lasko calls Marc “a minor painter associated with a major group” and says Marc is “a no more than competent painter rooted in nineteenth-century naturalism.”

li PAN, Vol. 2, No. 19 of 28 March 1912 in Franz Marc: Schriften, (Cologne: DuMont, 1978), 97. “…Qualität erkennt man nicht am Glanz des Nagels oder am schönen Schmelz der Ölfarbe; mit Qualität bezeichnet man die innere Größe des Werkes, durch die es sich von Werken der Nachahmer und kleinen Geister unterscheidet.”

lii Morgan, “Concepts of Abstraction,” 166. About interpreting Marc’s writing as “political,” Morgan says: “In this regard, Marc remained more faithful to the Expressionist ideal of revolt, of active rebellion.”

liii “The Soul of Man” in The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, eds. Russell Jackson, and Ian Small, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 231. On a related tangent, Wilde points out in the same paragraph that “…it is much more easy to have sympathy with suffering than it is to have sympathy with thought.”

liv Marc, Postcards to Prince Jussuf, 15. “People do not deserve us, and that is why we are here at Sindelsdorf,” Marc comments to Else Lasker-Schüler at the beginning of 1913.

lv Klaus Lankheit, Marc’s biographer and the man who compiled one of the first catalogue raisonnes devoted to Marc’s work suggests Marc encountered, or created, numerous personal and legal difficulties on theses excursions. See: Lankheit, Franz Marc : Sein Leben U. Seine Kunst.

lvi Marc,

lvii Hope in the way that Marc expresses himself about the future is not the same thing as positivism or even optimism. Marc’s hopefulness is an emotion, a yearning, not a concrete expectation.

Leave a Reply