It is my intention, in reading together literary critics, artists, and theorists, to show how the development of Shakespeare’s conception of his own subjectivity develops over the course of his sonnet sequence. I will discuss and utilise the Jungian concept of individuation, and the Lacanian concept of desire, as well as language from the lexicon of the fifteenth and sixteenth century alchemists to develop an understanding of how the intimately psychological nature of the production of art is being demonstrated by Shakespeare in his poems.

The theme which is of paramount importance for my discussion is that of desire, and how it relates to love, language and the production of art itself.

My indebtedness to Margaret Healy’s Shakespeare, alchemy and the creative imagination: the Sonnets and A Lover’s complaint, and Carl Jung’s Psychology and Alchemy is indelible, for it has afforded me the opportunity to open a dialogue between psychologists and literary critics centered around Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence and in doing so develop a rich conceptual framework for understanding that particular poet’s subjectivity.

I will explore first and foremost the relationship between works of art and their creators. A poet for whom this relationship appears most vital is Sir Thomas Wyatt. In his translation of the sixth psalm of the New Testament, Domine ne in Forure,1 he enunciates his own wish to “remain in” the Lord’s “protection” (l.112), so that the variety of enumerated “foes have none access” (l.96) to the peace of mind afforded to the poet by his supplication to God’s mercy. Wyatt states that his very “flesh is troubled” (l.28) by his search for God’s forgiveness, the “only comfort to wretched sinners all” (l.5). Amongst the “foes” that Wyatt wishes should “have none access” to his “harp,” are “the mermaids” and their “baites of error” (l.93). Wyatt here brings together two musical images.

By representing himself, or more precisely his soul, as a harp, and alluding to the song of the sirens which Odysseus defends himself against in Homer’s epic poem, Wyatt is doubly emphasising the creative, artistic nature of his repentance. As a work of poetry the text dramatises his desire metaphorically, as an instrument that can be manipulated by God or by the “mermaids,” and moreover Wyatt’s wish is carried by the words of the poem itself, as expressions of that desire. Thus Wyatt signifies himself both in and by his poetry, the words themselves and the act of enunciating them, shifting his desire between the production of the poem and the poem itself. The King James version of the Bible associates Psalm 6 to “the chief musician upon Nehiloth”2 suggesting the Psalm is to be sung to a musical accompaniment, the Nehiloth being a stringed musical instrument similar to a harp. Wyatt’s song thus competes with that of the mermaids,” suggesting again the malleability and fragility of Wyatt’s call for God’s mercy. Desire is here then characterised and expressed as working in and through art, particularly poetry and music, and in both cases Wyatt characterises himself as maker and creation, susceptible to both the mermaids and God’s will while at the same time evidencing this susceptibility through a specific act of poetic production. A third way in which Wyatt presents his plea can be discerned by the image of the mermaids themselves. For if they represent something which would exclude him from God’s mercy, they represent a negative aspect of desire and, I would argue it is, the selection of that particular image which qualifies his poem as undergoing a decidedly alchemical process.

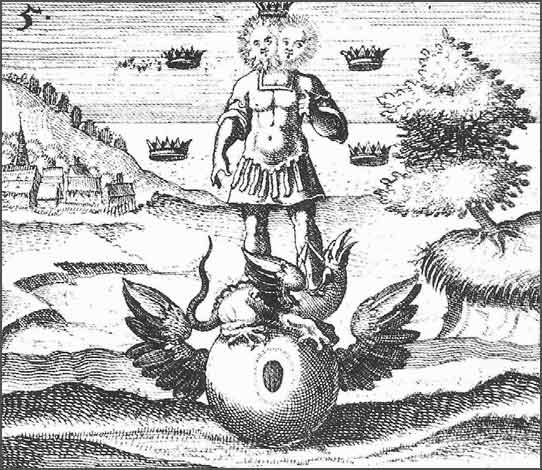

Wyatt’s mermaids are, as Carl Jung would have it, an artistic integration of certain elements of the human psyche characterised as “unconscious” with other “conscious” activity. Amongst the unconscious part of the psyche are “instinctive, involuntary” emotions “which upset the rational order of consciousness by their elemental outbursts.”3 The particular outburst of desire articulated by Wyatt occurs in order that he is able to literally come to terms with his wish to acquire God’s mercy. Moreover, the image of the alluring mermaids” song is opposed to that of the music produced by God’s playing upon Wyatt’s “harp,” giving the reader a musical conjunction of the negative and positive influences that the heavenly or earthly players might have upon his soul. In the alchemical lexicon, The fusion of these images generates, a rebis,/em> or hermaphrodite figure representing just such conjoined opposites as are present in Wyatt’s text:

Wyatt’s rebis is his text and like the Alchemist seeking to explore the nature of matter Wyatt has projected “the unconscious into the darkness” of his poetry in order to illuminate his soul with God’s mercy. Furthermore, the image of the hermaphrodite is, for Jung, the capitulation of the process of psychological individuation. The movement of Wyatt’s poem thus mirrors the movement of the psyche, it is as if Wyatt’s own psyche is producing, and in turn becomes produced by his work, just as the opus of the alchemists was the philosopher’s stone itself, again represented by the hermaphrodite or rebis. As a form of self-fashioning, it is crucial to this alchemic process in poetic form that the self be represented in language, and that representation be transfigured, moving between opposing poles of a given value system before arriving at a compromise between them. As a second stage of my argument I would suggest this process is not limited to the play of images within a text, but crucially affects the way the author himself comes to understand, and in the case of Stephen Greenblatt be understood by, his text.

In the first chapter of his Renaissance Self-Fashioning, Stephen Greenblatt reads Holbien’s “The Ambassadors.” The painting is for Greenblatt an exemplar of the ways in which “the power of human shaping was exercised in the Renaissance. The figures of Dinteville and Selve, Greenblatt argues, are crafted by Holbien to give the impression of two men “in possession of the instruments, both literal and symbolic, by which men bring the world into focus, represent it in its proper perspective.”5 The courtiers possess not only mastery of “the arts and the sciences, the power of imagery and the power of words” (p.19), as signified by the objects placed around them, but the ability to fashion the world itself, and are thus caste as gods, in mans” image.

What is curious, however, about Greenblatt’s reading of the painting is the way in which, and the point at which, he breaks off his analysis of the meaning of the anamorphic skull in the centre of the painting. The main effect, and the most powerful feature, of the painting is undoubtedly, as Greenblatt notes, that one must “efface the figures” in the painting “in order to see the skull” (p.20). It is only “when one takes leave of” the decidedly artificial world created world of fashioned selves that the skull becomes visible and therefore brings “death into the world” (p.21). The skull is thus not only a reminder of the insubstantiality of the identities of the figures represented, but demonstrates that if death confers some form of reality upon the self-counterfeiting courtiers, that reality is in a space not locatable in the painting itself, the one place which we might assume it is represented most clearly. Structurally speaking, the skull holds the painting together by counterpoising everything represented in it against the spectre of death. Without the non-space which the skull occupies the, apparently, real space of the painting itself would disappear, that is to say, the presence of the courtiers is dependent upon the possibility of their absence, as demonstrated by the presence of a skull which strictly speaking is not anywhere present.

Here, as in Wyatt’s poem, Greenblatt is commenting on the commensurability of two opposites, namely the vitality of the courtiers and the skull, which renders them inanimate. It is at this point Greenblatt breaks of his analysis, without acknowledging that the courtier’s identities are no more or less illusory than the skull itself. He does of course assert that the skull is in itself a “spectacular display of the artist’s engineering and skill” (p.20), but this is no more nor less so than any other element in the rest of the painting. It is not as if the fashioning of the figures is any different from the fashioning of the skull, that is to say in no way is the sense of self created by the myriad artefacts, books and maps in the painting any different from the sense of death created by the skull. If, in the painting, “life is effaced by death, representation by artifice” (p.19) then even more so illusion is effaced by illusion. Greenblatt fails to recognise the way the Holbien painting functions as a kind of rebis, to use Jung’s terms, bringing together in representation diametric opposites. Furthermore, I would suggest what Greenblatt does not take into account is that at no point is there any substantial self to be fashioned or effaced, only the illusion of the courtiers identities which is dispelled by the illusion of the skull. Greenblatt, I would argue, separates the courtiers and the skull into categories which are not necessarily exclusive; in fact what the paining represents, is that the self is nothing more than the movement of metaphoric illusion, and just like the alchemical rebis produced by individuation, the self is produced merely by the fashioning of images, nothing more.

What is particularly striking is that Holbien dramatises this process of illusion as requiring one to move across the canvass of his painting in order to read it, thus showing that however illusory the self may be, it is none the less produced by a physical process. In alchemical terms the physical process in question is the transformation of the primal first matter, “a confused mass,” containing “in itself all colours and metals,” which is compared by the alchemists to “everything, to male and female, to heaven and earth to body and spirit and to chaos,”6 which like in Wyatt’s text, is often represented as a mermaid.

This prima materia is, psychologically speaking, transformed from an unconscious form, in Wyatt’s case desire, into conscious reconciliation, as in Wyatt text. What is crucial to this process is that alchemical texts the stone itself, like the conceptions of self in Holbien, Greenblatt and Wyatt, is never named. It is as illusory as the selves fashioned in each text. I would therefore wish to distinguish between the self presented in the text, and the self of the author who produces the work itself. What the alchemical and psychological process shows is that an understanding of how both senses of self work together, not in so much as they are the same, but that they are commensurate, each one working to transform the other.

Given that, as I have shown, the illusions of the reality of the courtiers” identities and the illusion of death which supports and effaces those identities are one and the same illusion, one single rebis, it is strange that Greenblatt does not observe that exactly this process is occurring in his own illusion of identity, his Renaissance Self-fashioning. In the epilogue of his book Greenblatt states that his own reason for composing the text was to affirm his own sense of identity, of the way in which he needs to “sustain the illusion” that he “is the maker of his own identity” (p.257). It is a paradox that he sustains this illusion by yet another illusion, the illusion of an autonomously fashioned self as demonstrated by Holbien’s painting. In a mirroring of “The Ambassadors,” Greenblatt’s text exchanges illusions of selfhood in precisely the same way that illusions of self and the illusion of death is exchanged by Holbien. Moreover, just as in the Holbien painting the illusion of self as real is not so much effaced but sustained by the illusion of death, the illusion of Greenblatt’s sense of self is similarly sustained by his text. What is evident in both cases is that the metaphoric movement of Greenblatt and the courtiers” desire literally imparts upon them a sense of being which is, I would argue, directly analogous to Jacques Lacan’s conception of sublimation.

For Lacan the “turning point when the artist completely reverses the use of that illusion of space”8 — otherwise termed anamorphosis and the central process at work in “The Ambassadors”— is nothing other than the goal of art itself. Art is thus not an effort of imitation, rather, and with particular pertinence to painting and poetry, art is the imitation of an imitation, or the shadow of a shadow, just as the skull in Holbien’s painting is the “shadow of the shadow of death” (p.21). What is being represented is precisely nothing, as the ambassadors themselves are shown in the final analysis to be as surreal as the illusion which dispels their constructed selfhood, so Greenblatt’s false senses of self stated in his epilogue is sustained and dispelled by the artificial notion of self demonstrated in his book.

What is crucial in Holbien, Greenblatt and Wyatt’s pieces is that the illusory suspensions of a sense of self are commensurate with, in each case, a desire, and that the desire is signified by a series of exchanges of words and images with nothing, literally no-thing, as their referent. Greenblatt is writing in order to rescue a feeling of autonomy, while the courtiers are painted in order to present themselves as possessing “the highest hopes and achievements of their age” (p.17), while Wyatt wishes to attain God’s mercy. Another Renaissance artist, Micheal de Montaigne, demonstrates, with particular pertinence to my exposition of the movement of desire in art, how his medium itself is critical in the alchemical process of artistic self creation. As Margaret Healy asserts, “Montaigne reveals that through the operation of his mind and his pen, he reshapes, indeed transforms, the bleak and fearful reality of his illness into a more acceptable and palatable piece of theater.”9

Montaigne’s illness, his kidney stones, became the subject of his writing to the point where, in his essay Of Experience, he speaks of his entire project as posing a series of questions, circling around his conception of his affliction. He asks “what nature is, what pleasure, circle, and substitution are,” and crucially, he asks himself what a stone is, and answers that “a stone is a body,” and a body a substance. Here the stone is submerged in a series of other concepts which relate to each other as nothing more than a chain of nouns. Before his line of reasoning becomes a rhetorical reductio ad absurdum, Montaigne pauses to show his realisation of the fact that, in this way, he simply “exchanges one word for another,” curing himself, and allowing, as Healy shows, his illness to become “an art form with the capacity for emotional healing” (p.242). Montaigne is, like the subjects of Holbien’s paining and Greenblatt, constructing himself in a chain of signifiers in order to transform his desire into something palatable. Monatigne’s work is then, above all, as William Hamlin attests, an attempt to “co-substantiaite” himself with his text, so that the “I” of his text is something which his “writing continually modifies.”11 This is not to say that Montaigne’s experience of his own illness can be reconstructed from his text in a kind of biographical literary criticism which would conflate “a life a man and a work” (p.724), rather the evidence of Montaigne’s engagement with his illness through his work is that which shows the place of his desire as moving through the chain of signifying substitutions. The cure is not the work itself, but the way the work is written; that is to say Montaigne’s “I” is to be found in the enunciation of his text, rather than what is enunciated.

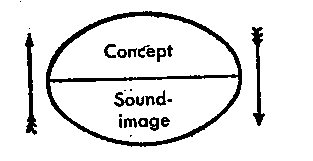

Furthermore, reading the Montaigne alongside the three other artists shows that the movement of desire functions in a strikingly similar manner to that of language itself. As Ferdinand de Saussure identified in the Course in General Linguistics12, “the linguistic sign is arbitrary.” Thus is one takes each piece of art to behave like a signifier, the desire of each artist moves between, in Greenblatt’s text, self and text, and in the Ambassadors case presentation of self and effacement of self, so that what signifies the artists themselves is not the concrete picture or text but the relationship between artist and work of art. This relationship, I have shown, is arbitrary due to the movement of desire in a metaphoric chain; that is to say the way in which the artists signify themselves only has meaning as a process of production, the relationship between representations within each work has no final connection to the artist. Moreover, the fact that Holbien depicts a process of self-presentation and self-cancellation in terms of the vitality of the courtiers and of the fore-grounded skull, shows that the movement of desire confounds traditional dichotomies. Desire, and the artists” self-fashioning, thereafter can be read like a language, even if it cannot ultimately be called a language in and of itself; it is simply structured in the same way. That is to say the relationship between the artist and his text is the same as the relationship between signifier and signified, just as the artists relationship to their own desire is structured in the same way. I would thus argue parallels between the movement of desire, the construction of a sense of self and the structure of language as all being deeply psychological process and, I will argue, all present at work in alchemical individuation. The thread that ties these seemingly disparate concepts together is that of representation, the alchemical rebis which is the goal of the alchemical process itself, the attainment of the philosopher’s stone by the process of what Jung terms projection, Lacan terms sublimation, Greenblatt terms self-fashioning and Wyatt terms repentance. As I have demonstrated, each work of art as a microcosm of those processes and in what follows I intend to read Shakespeare’s Sonnets in a similar way.

Desire and the Dark Lady

The first line of Sonnet 13013 evidences precisely how the Sonnets are alchemical in nature. Shakespeare states simply at the poems opening that “my mistress” eyes are nothing like the sun” (l.1). The sonnet appears at a point in the sequence of poems where, as Joel Fineman asserts, Shakespeare confronts a “desire which is always structurally unsatisfyable.”14 Before engaging in a more meticulous way with Fineman’s characterisation of desire, I would suggest that, amongst the ways in which I have shown desire can be read into a text, the most crucial is at the level of the syntax of a sentence itself. The line, which first appears condemnatory of his mistress, actually contains a sticking ambivalence in tone. This ambivalence hinges around the word “nothing.” The line can be read to mean simply that Shakespeare does not find his mistress” eyes at all comparable to the sun, which would be deprecating, her eyes representing complete blackness and so negating their purpose; one cannot of course see at all without the sun’s illumination. A second way to read the line would be to understand the meaning of “nothing” as “no-thing,” suggesting that her eyes, like the sun, are unlike anything else, rendering the line a statement of praise comparable to those he uses to aggrandise the “lovely boy” in the early part of the Sonnet sequence. Moreover, if the word is excluded from the sentence then the meaning is very clear, and very complimentary, it would read “my mistress” eyes are llike the sun.” The presence of the word “nothing” then would appear at first to completely negate that simile, but situated in the centre of the line it affects neither negation nor emphasis of the compliment, it means literally nothing, neither adding nor detracting from the meaning of the sentence but rather confounding the senses of a line that can be read as an insult, an expression of disappointment, an expression of frustration, or indeed a expression of deep praise.

I will return to this line later on in this dissertation because I hold it to be crucial to the way Shakespeare expresses his desire, but what I hope to have shown thus far is that the word “nothing” functions, as in all the texts discussed thus far, as a rebis, or the skull in the Holbien painting, or Wyatt’s mermaids. For the singular word which means both nothing and no single thing, therefore everything, is a hermaphrodite in language, and as physically moving across the canvas of “The Ambassadors” effaces the indented meaning of the painting, so reading the first line of Sonnet 130 turns the compliment into an insult, or visa versa.

Furthermore, as a display of anamorphosis, there is here a kind of sublimation of Shakespeare’s desire, projected into his mistress” eyes. For desire is to read in this Sonnet as the interposition of the word “nothing” which strictly speaking function, in terms of the syntax of the sentence, to negate the simile: before the word is introduced the sentence is an expression of praise of, and thus desire for, his mistress, afterwards condemnation. It is for Lacan, on a psychological level that “there is a whole world of no-saying, of interdiction” in which form the “unconscious essentially presents itself” (p.78). It is in the negation that Shakespeare’s unconscious presents itself, or rather it is the negation which shows how in representing his desire Shakespeare is constrained by his syntax so that what is enunciated, which has only one disparaging meaning, is different from the enunciation, which has myriad possible interpretations. Thus Shakespeare’s desire is sublimated, and altered, like that of Greenblatt, Wyatt, Montaigne and the Ambassadors by the transfer of themselves in an artistic medium, which reveals how the process of projection takes place on a number of different levels in the inter-relation of art and artist. For Jung it was no coincidence that the Alchemists themselves used the very word “projectio” to describe their process of transforming the “prima materia” into the philosophers stone by representing in matter the unconscious parts of themselves. What I intent to demonstrate from this point forward is how the processes of projection and sublimation, both of which lean inextricably toward individuation, or the completion of the Alchemical opus, and which I have shown to be present in macrocosm in a number of different texts, function in the macrocosm of Shakespeare’s Sonnets.

Desire and the splitting of the subject

Thus far I have shown the relationship between the artist and the desire detectable in his work to be arbitrary, that is to say the relationship can be depicted as fulfilling the criteria of Saussare’s representation of the linguistic sign:

I have argued that the “sound image” can be understood as the author and the “concept” as his work, while the force of signification, that links the two hemispheres of the circle, is nothing less than the movement of sublimated desire, represented here by the arrows. To illustrate this in more detail I will read the remainder of Sonnet 130, and in doing so fully demonstrate the parity between Saussure’s structure of the sign and the movement of desire in poetry.

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red;

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound;

I grant I never saw a goddess go;

My mistress when she walks treads on the ground.

And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare

As any she belied with false compare.

Here Shakespeare demonstrates the “fickle ambiguity” as M.L.Stapleton put it,16 that characterises his attitude toward the dark Lady. There is a clear attempt to dichotomise the very human physicality of his dark lady with natural non-human designators of beauty. Thus the natural colour of “coral” is “far more red” (l.2) than the hue of the dark lady’s lips, and “roses damasked, red and white” are so unlike her cheeks that this disparaging disjunction is made emphatic by the enjambment of lines 5-6 themselves, placing emphasis on the differences evoked by separating them spatially within the structure of the sonnet. There is, I would suggest, far more being said by Shakespeare in these comparisons than simply a reversal of the conventions of courtly love poetry by “personalising” the dark Lady, as opposed to the more usual presentation of the “impersonality and repose,17 to use Frederick Goldens” terms, of the lady in question. Certainly the sonnet is deeply personal in a physical sense, with Shakespeare deriding aspects of the dark lady’s appearance, but as I have shown to be present in line one of the sonnet, the same disjunction between desire and the expression of that desire is also present in the lines succeeding it.

This is not purely a matter of showing how the couplet following the volta of the Sonnet is expressing a different sentiment to the preceding four quatrains. For indeed it appears as though in concluding his sonnet Shakespeare is evincing his distaste, or puzzlement, at the fact that he is somehow at odds with himself, in thinking his “love as rare” as any other woman she “belied with false compare” (ll.13-14), but what seems clear is that this puzzlement is a direct questioning of the poet himself, that is to say, it is to Shakespeare whom Shakespeare directs the final couplet of the sonnet. Stapleton elides Sonnet 130 completely, preferring to discuss the sonnets directly preceding and following it in order to conclude that Shakespeare’s ambiguous attitude toward his mistress is a result of his own incapacity to restrain his own “ungovernable lust.” She quotes line ten of sonnet 129, which uses three forms of the verb “to have,” in the past, present continuous and present tenses respectively to indicate the “extreme” (l.10) nature of the poet’s sexual desire for sexual possession of the dark lady, a desire which he grants is of his own making, have admitted later in the sequence that his mistress” “black is fairest” in his “judgements place.” Undoubtedly the dark lady sonnets do show as, Stapleton argues, a sense of self realisation by the poet about the nature of his sexual desire being at odds with the real, physical nature of the dark lady herself, but for Stapleton to argue that the confusion he feels in wrestling with his own lust is caused perhaps by “love, or the ardour that his love kindles in him,” or indeed by his “constantly changing mind” (p.219) is to overlook the fact that, as I have already stated, the confusion can be conceptualised as evidence of what I would call “split subjectivity” displayed by Shakespeare in precisely the sonnet Stapleton elides.

In order to elucidate the process by which Shakespeare disjoins himself from himself it is necessary to refer back to the final couplet of Sonnet 130 and question to whom exactly Shakespeare is expressing his puzzlement at loving someone whom he also finds repulsive. He is of course addressing himself, but he has split his subjectivity into two different agents, the agent who speaks of his disdain for the dark lady and the agent who creates the elaborate images of “roses damasked” (l.5) and “coral red” (l.2). De facto, the frustration felt in the last two lines of Sonnet 130 is expressed from Shakespeare qua sonneteer, to Shakespeare qua desire, and this movement between subjectivities is evidenced in the syntax of the lines themselves. For, as I have shown previously by reading the first line of the sonnet, desire is evidenced in the enunciation of a statement rather than in what is specifically enunciated, and it is foreclosed by the syntax of the sentence itself.

To read the sonnet in this way requires that the expression of desire be determined by that very syntax, thus in Sonnet 130 Shakespeare’s desire, which is clearly for the dark lady, is frustrated and foreclosed by very way he structures the quatrains themselves. The similes Shakespeare uses to compare the physicality of the dark lady to the beauty of nature are a stark textual reconstruction of the split in his subjectivity, as is evidenced by lines 9-10 where despite the fact that “music hath a far more pleasing sound than his mistress voice he still loves to “hear her speak.” Thus the poet’s desire to hear his mistress voice is frustrated by his knowledge of the comparable pleasure afforded by music, which is not an insult as such, Shakespeare is not stating simply that music is more pleasant than the dark lady’s voice, but this line is rather an articulation of his inability to express his desire in poetic form; it is an articulation of frustrated desire rather than, as Stapleton would have it, a derision of his mistress.

Moreover this desire is detectable in the way the sentence is enunciated, the first line reading as an expression of the desire and the second of a frustration of that desire as soon as it is articulated in language. The desire is still articulated, and it is the lines of poetry themselves which frustrate Shakespeare qua desire. Shakespeare’s split subjectivity is felt fully in the repetition of the first person pronoun in line nine:

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound;

The first instance of the personal pronoun in these lines I will term Shakespeare qua desire and the second Shakespeare qua sonneteer. It is not enough to say here that the movement of desire in these lines is nothing more than, as Fine characterises it, a “duplicitous representation that ruptures formal correspondence,” due in the most part to the dark ladies “differing heterogeneities,”18 which Shakespeare struggles to reconcile, rather it is the splitting of Shakespeare’s self which is evidenced in these lines, for by the time the reader has finished the third quatrain the first “I” has been completely elided by the second, whereby the full frustration of Shakespeare’s derision is felt and one is left wondering whether he loves to hear his mistress” voice at all, any residue of that particular desire being lost in the completion of the pentameter of line ten, where the only sound audible is the pleasant music whose image thereafter occupies the entire line. This illuminates Lacan’s definition of the subject as “nothing other than what slides in a chain of signifiers,” crucially, “whether he knows which signifier he is the effect of or not.” The subject is thus engendered in language rather than, as Fineman would have it, by the conscious utilisation of that language. The subject is here the “intermediary effect between what characterises a signifier and another signifier, namely, the fact, each of them is an element.”19. Shakespeare’s subjectivity is to be read in the very discrepancy Fineman would ascribe to the poets characterisation of the dark lady herself, that is to say it is at the points in which the personal pronoun looses it’s distinctness from the signifiers that surround it and becomes elided beneath the chain of signifiers that comprise the complete enunciation of a statement, and a fortiori the subject himself can be determined. Thus Shakespeare’s desire is what links the two lines together, even as that desire moves between the “sweet music” (l.10) and his dark ladies voice.

Furthermore, the split in the subject, and the effects I have just described are related exactly as depicted in Saussare’s algorithm for the sign, for the incommensurability I have just discussed as being present in the subject in the process of enunciation and in the process of enunciating, is barred in precisely the same way as the signifier and signified, and the completed sonnet, like the complete sign, is marked by an internal discrepancy, just as the subject and his desire is split.

Nevertheless, I will re-iterate, the bar is crossed by the desire, even if, as in Sonnet 130, it is only frustration read in the chain of signifiers, which comprise the poems statements, that links the two halves of the subject together. What I am concerned with here is how the act of signification itself ties the artists desire to his work, and in every text discussed up to this point I have shown how artistic production is nothing less than the production of desire in language, that is to say, as a process of signification. Yet it does not suffice merely to assert, as Stapleton does concerning this particular sonnet sequence, that Shakespeare’s struggle with his desire for his mistress results in any straightforward process of self-realisation. For as Stapleton would have it, a line such as “all my vows are oaths but to misuse thee” from Sonnet 152, show Shakespeare to have realised something about his attitude toward the dark lady. However, this conception of self-realisation can only be brought about if the poet is considered as two different entities, namely a subject to observe, or Shakespeare qua sonneteer, and a subject to be observed, namely Shakespeare qua desire. What is clear is that Shakespeare’s subjectivity, although split, exists in a dynamic relation whereby the enunciating subject and the subject enunciated are in a mutually dependant relationship, that is to say, to be other to yourself is to be yourself. The result of this is that there cannot be a process of realising something about the self by a second part of the self as each part is instrumental in determining the other; thus Sonnet 130 shows that the self can be characterised as split but not separate.

Sublimation of the split subject

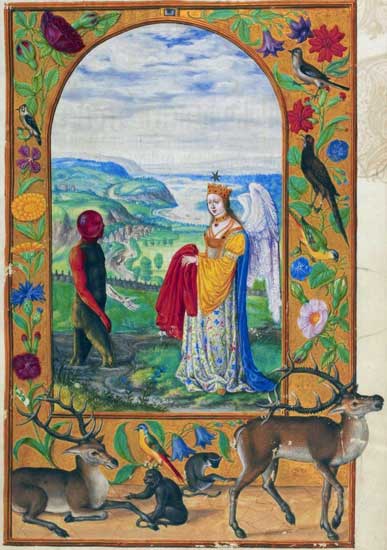

What I have shown to be demonstrated by Shakespeare’s meditations upon his mistress is an articulation of frustration. This frustration, or struggle to express desire within the confines of the sonnet form, is a further example of an “unconscious outburst” like those enunciated by each artist discussed up to this point, but particularly Sir Thomas Wyatt in his religious poem “Domine ne in furore.” The difference between Wyatt’s exclamation and Shakespeare’s however, is that Wyatt sublimates his desire by conjoining two poles of a binary opposition, such as the word of God and the song of the mermaids. There is, in Wyatt, a complete sense that the unconscious desire has been successfully expressed and so individuated, thus it can be represented as a rebis, alluding to the fact that his desire has suspended its dichotomy and been subdued by the production of the work of art itself. Shakespeare, conversely, has not allied his physical lust for his mistress with the romantic sentiments such as those expressed in the opening of each line of Sonnet 130, indeed, the dichotomies are enhanced by the enunciation of the poem itself. In alchemical terminology the dark lady sequence can be described as Shakespeare’s nigredo. The nigredo is, as Jung asserts, “the initial state, a quality of the prima materia, the chaos or massa confusa“20 of the self yet to be fully individuated. The nigredo is often represented in Alchemical texts as “the mighty Ethiopean, burned, calcined discoloured, altogether lifeless,”21 and in images such as this from sixteenth century alchemist Trismosin’s Splendor Solis:22

The plate here clearly shows the “mighty Ethiopian” emerging from the water. This emergence from the water is nothing more than the purification of the prima materia itself, an allusion in Jungian terms to the integration of the chaotic unconscious into the conscious mind, shown by myself to correspond to the movement of desire though sublimation in art. What I have shown to be crucial to this process is the act of signification, or what strictly speaking is the way in which an artist’s work comes to stand for his desire, as in Sonnet 130. Indeed, as the twentieth century inheritor of Jung’s legacy Lacan states explicitly, the signifier’s displacement determines subjects” acts, destiny, refusals, blindnesses”23 — Shakespeare is all too blind to his own desire, as I have shown, in the dark lady sequence of his sonnets.

What Lacan terms the “signifierness” of the signifier, that is, the arbitrary nature of the sign, which becomes open to a cacophony of semantic polysemy, is the very effect of poetry. What curtails and frustrates Shakespeare is precisely that his statements about the dark lady are imprecise. Thus word “red” in line two of Sonnet 130 appears twice, but each time in a different semantic context, firstly as a way of describing coral and therefore signifying beauty, and secondly to deride the lips of his mistress. What is exactly at stake for Shakespeare is that the two instances of the same word do not carry, to use Gottleb Frieg’s terms the same “sense.” The reference is the same, red refers in both cases to the colour of the spectrum, but the sense is dichotomised between insult and exultation, leaving Shakespeare’s desire confused, in the manner alluded to in the nigredo of the alchemists.

However, the opening of semantic possibility is precisely what is necessary to individuate, even if, as in the case of Stephen Greenblatt, the work of art produced by individuation has no bearing on the initial desire that produced it. For if Greenblatt’s intention was to produce a treatise for a coherent sense of self, then his Renaissance Self-Fashioning only proves that such a sense is impossible to find. Thus even if exactly the opposite result is produced from what was initially intended, the sublimation of desire found in art nevertheless succeeds in satiating his desire, even if that desire is only moved metaphorically between art and artist. Thus it is enough that the semantic possibilities have been opened and foreclosed in a work that desire, for the subject, no longer lays a hold on his subconscious.

This is expressly the difficulty critics like Stapleton have in reading the dark lady sonnets, because there is not in the sequence evidence that Shakespeare’s sublimation has been foreclosed, that is to say the vehicle for the tenor of his desires is still his mistress. It is necessary to signify desire in terms other than its intended object for it to be successfully sublimated, that is to say to produce a tenor that is different from the vehicle of the artists initial desire. Shakespeare’s dark lady sonnets have not shown his lust to be signified in terms other than the physicality of the dark lady herself, and thus the desire remains unsatisfied, and the poetry itself expressing all those signs of frustration Stapleton shows it to bear. Thus to conclude that the “unreliable” Shakespeare of the dark lady sonnets is a “creature of fiendish ambiguity who distinguishes himself as a teller of lies” (p.230), as Stapleton rather hastily does, is to simply ignore the fact that Shakespeare is still sublimating.

Moreover, this perpetuation of sublimation is in keeping exactly with the conventions of the genre he is writing in. For it only takes a glance at Barbara Tuchman’s categorising of the medieval code of courtly love24 to realise that the defining characteristic of this genre of poetry is that the lady is never obtained. The lover must at all costs “worship the lady from afar” and crucially have his “passionate declaration of love” rejected by the “virtuous lady.” Thus what absolutely must not occur is the satisfaction of the courtly love poet’s lust. The process of sublimation must continue displacing the desire of the poet elsewhere than the object of the poems themselves, even to the point where when presented with what he most desires the poet is forced to deride it.

This is clearly evidenced by another, but not contemporary courtly love poet, Arnaud Daniel. His poem “Pus Raimons e Truc Malecx,”25 which survives in two separate manuscipts, the later transcribed by the Provencal editor Giulio Camilio, “breaches the boundaries of pornography to the point of scatology,”26 as Lacan observes, and the “delight of a number of startled” (p.199) critics who have subsequently read the poem is at least proportional to the consternation directed at the derision of his mistress in Shakespeare’s Sonnets by writers such as Stapleton.

Arnaud describes a conversation between a pair of courtiers, Raimon and Malecx, on the subject of a particular request by the love object of a third courtier, Bernard. The fulfilment of a particular demand by a lovers lady is exactly in keeping with the conventions of courtly love, as is evidenced by the rules of love given by Andreas Cappelanus in his De Amore, believed to have been written around 1184,27 which states that “the value of love is commensurate with its difficulty of attainment” (p.106), that is to say the favour Bernard wishes to obtain is given at the price set by his lady. The request that Bernard’s lady has made is simply that he consummates his relationship with her. What is especially surprising about this request is that is exactly that which the courtly lover should not be permitted to do; the attainment of his lover physically is exactly that which must be avoided, because it is exactly in the process of avoidance that the love object can be given its value, for example by the composition of love poems. Indeed, both Arnauld and Shakespeare do, as Lacan attests, push “desire to the extreme point”28 by offering even their lives in exchange for physical satisfaction, Shakespeare in sonnet 147 stating explicitly “desire is death,” and Arnaud in “L’aur Amara” complaining how he dreads “to die if” his desire for his lover isn’t eased. (l.17)

Although both poets use the “world upside-down trope” to place death as the highest, and therefore most worthy price given for attainment of a very live, worldly, desire, which, as Gerard Gourin shows in his study of courtly love poetry,29 is characteristic of the genre, yet it appears paradoxical that the very thing at which the courtly love poet aims should be depicted in such derogatory terms as those Shakespeare and a fortiori in Arnaud’s work. The paradox is resolved when the poems are read as effect of sublimation “in its liberality, in its authenticy,” to use Lacan’s phrasing (p.202). For the entire edifice of courtly love is built precisely on the premise that desire moves, in the ways I have shown thus far in my reading of the artists up to this point, in a metaphoric chain, away from its indented object, so that, I re-iterate, its structure resembles that of the sign. Even when presented with the object desire is driven towards, sublimation moves the desire and fixes it on another object. Thus what courtly love poets demonstrate is that by acting as an effect of signification, desire is evidenced in, to return to Frege’s30 terminology, the sense of the enunciation, rather that references contained in the statements themselves. Thus it is necessary to suspend even a discussion of Shakespeare or Arnaud as misogynistic, and rather see the poems as a perpetuation of the desire and therefore as yet another link in the chain of signification which leads the subject to be alienated from his own desire, in exactly the same way as each line of the quatrains of Sonnet 130 move Shakespeare away from his own lust, even as they depict with increasing clarity the object of that desire.

Desire and Signification

In the third partition of the Anatomy of Melancholy, Robert Burton lists a number of definitions of the difference between love and lust. He settles on the differentiation made by Leon Hebreus, in which it is stated that while “desire wisheth, love enjoys; the end of the one is the beginning of the other; that which we love is present; that which we desire is absent.”31 I have shown thus far how desire always draws the subject away from the particular from the object it is intended to enjoy. What I am concerned with is designating is how love can be seen as the beginning of desire, or desire as the end of love, that is to say, at what point desire and love are separable, especially as that is exactly, I will argue, what Shakespeare is conceptualising in his Sonnets. Psychologically speaking, Freud nominated two “currents” of libidinal activity, the “affectionate and sensual,”32 a dichotomy between the emotional and sensual, mirrored in Shakespeare’s attitude to the dark lady, and one which is circumscribed by the sublimation of his desire away from even that at which it aims. Lacan re-formulates Freud’s dichotomy, terming desire “neither the appetite for satisfaction nor the demand for love, but the difference between the two.”33 Desire can be conceptualised as the point at which the demand for love exceeds the satisfaction of the Freudian “sensual current” and what remains is the movement of the affectionate current. There is a sense in which therefore desire can be said strictly to be neither sensual nor affectionate but, to extend Freud’s metaphor, to be the stream through which both currents flow. I will now demonstrate how the process of signification itself can be seen as the stream in which desire is carried, that which links artist to work of art and subject to his desire, even if, as in the dark lady sonnets, that desire is extrinsic to the subject himself, due to the split in any single subjectivity. This entire process of evincing and artistically expressing desire and, crucially, that articulations dependence on signification, is demonstrated by what I will show to be Shakespeare’s other creative nigredo, or Othello, and in particular the protagonists relationship with his love object, Desdemona.

It would appear as though Desdemona is described in diametrically opposed terms to the dark lady. Othello describes her, in the final scene of the play, as being of such value to him that even “another world” “of one entire and perfect Chrysolite”34 would not be worthy to be given in exchange for her love. For critic John E. Seaman, this description of his wife by Othello is “inappropriate to his emotional state”35 emphasising rather “the symbolism of Desdemona’s role and Othello’s bad judgement.” (p.83) Seaman’s argument is that Desdemona, by virtue of her “true virtue and chaste nature” (p.84) is capable of “transforming the rough character of Othello into something finer (p.84), and that Othello, precisely by describing her in “the idiom of a merchant,” (p.83) thus negating his possible redemption by treating her as an object. Seaman sees this as bad judgement on Othello’s part, but comparing, as Seaman himself notes, a lover to a world made of such stone as is found to make up “the heavenly city in the Revelation of St.John” (p.83), is surely in some sense complimentary. Herein lies the parity between Shakespeare’s treatment of the dark lady and Othello’s treatment of Desdemona, for in both cases the difficulty is with the signification of desire. This difficulty is compounded on a critical level when Seaman takes the comparison between Desdemona and a precious stone literally, as if Othello is a merchant who would trade Desdemona for a world made of Chysolite. If such a world existed. The fact that it doesn’t only emphasises further not the symbolisation of Desdemona as commodity, but the magnitude of the value placed on Desdemona by Othello. What I am suggesting is that Seaman is reading, to use John Stewart Mill’s terminology, the denotation of the comparison Othello makes rather than the connotation. It is the comparative effect, rather than the comparison itself, which makes this line such a powerful expression of Othello’s emotional state. If considered as a metaphor, Desdemona is the vehicle and the world of chrysolite the tenor, and the agency which links the two is the effect of signification, which I have shown to be precisely the movement of desire, all of which shows the comparison Othello makes not to be a reduction of Desdemona to a natural object but, the exact object, for he is signifying his desire for her by creating a poetic relationship between his desire and the object of that desire, which I have shown to be the very process of sublimation in art up to this point in this essay. Indeed sublimation of desire requires that the “being to whom” the love poetry is addressed is, as Lacan intimates “nothing other than the being as signifier.”36 Indeed Shakespeare’s frustration in the dark lady sonnets is bought about precisely because he does not make the act of signification that would allow him to perpetuate his desire by sublimation.

In order to fully elucidate the interplay of desire and signification with the subject’s constitution in language, and thus the full allegorical meaning of the “mighty ethiope” of the Alchemists’ nigredo, it is necessary to show exactly what Othello and Desdemona represent for each other. In act one of the play, Othello recounts how “Desdemona would seriously incline” (l.163) “to hear” the “story” of his life. She found that when Othello “did speak of some distasteful stroke” (l.173) he had suffered, she gave him “for his pains a world of kisses,” and Othello states simply that she loved him “for the dangers” he had endured,” and he “her that she should pity them” (I,iii.181-2). Thus Othello and Desdemona represent something for each other different from themselves, literally in Othello’s case, where Desdemona loves him for how he represented himself to her. Thus her desire is signified by the exoticism of Othello’s passed, just as Shakespeare’s desire is signified by the physical qualities in which he describes the dark lady, and in both cases the desire is engendered by the act of signification.

Thus for Seaman to read Othello’s comparison of Desdemona to a jewel as a denotation of Desdemona’s devaluation into an object of trade is to misread the movement of desire. What occurs between Othello and Desdemona is the process whereby a subject presents themselves to any other subject, as one signifier to another signifier. This process results in what J.A. Miller calls the reduction of the “something into the someone.”37 It is not as if Desdemona reduces Othello to his history, but on the contrary, Othello becomes the person “she wished/ That heaven had made her” (I.iii.176), because of the way, literally, she reads him as a story. If the process of desire is engendered in signification, then what Othello depicts vividly is the extent to which the subject himself is engendered by that very same process.

Moreover, if the subject is constructed for another subject in language, the meaning of the lines Othello speaks in act five becomes even clearer. The comparison in which Othello evidences his desire is qualified by a condition, “had she been true” (V.ii.143). It is because Othello perceives Desdemona’s infidelity that he cannot make the comparison he wishes, even if, as I have shown, that comparison in fact demonstrates his desire. Thus the entire emotional force of Othello’s symbolic representation of Desdemona is foreclosed by the fact that some aspect of Desdemona’s presentation of herself contradicts the representation Othello has of her in his mind. This I would argue occurs on a purely linguistic level, as it is the image of Desdemona’s infidelity that torments Othello.

That image is symbolised by Desdemona’s handkerchief, which Iago did “see Cassio wipe his beard with (III,iii,484). The handkerchief here symbolises a symbol of Desdemona, namely her infidelity, and has the effect of signifying absolutely nothing, it is merely a lack of a lack of Desdemona’s faithfulness. Yet it causes Othello later in the scene to curse his wife, to “damn her” as a “lewd minx” (III,iv,524) and this prompts Emilia to ask, one act later why he should “call her whore.” (iv,ii,153). Shakespeare makes the textual nature of this word quite clear. Othello symbolises Desdemona as “this fair paper” which he himself cannot stand “to write whore upon.” (iv,ii,77-8). What is demonstrated here is that the effect of the subject as created in language leads to very real effects that would normally be considered outside of the domain of the signifier. Thus, even though, as Seaman shows numerous critics have observed, Othello refers to Desdemona as his “pearl,” she can also be considered his dark lady, as the signifier of his desire through which he sublimates not only his anger, but also his whole conception of reality. For “chaos” is indeed “come again” (III.iii.111) when Desdemona is thought of as unfaithful purely because he can no longer signify her, and therefore himself, in the way he had been doing up to this moment in the play.

The effects of this are felt in Othello’s language, particularly in act five, in which Othello’s eloquence is reduced to the stuttering syllables “O,O,O” (V,ii,225) when he responds to Emilia’s claim that he “killed” Desdemona, the sweetest innocent/That e’er did lift up an eye (V,ii,227-8) Othello of course killing his wife at the climax of the play, and it causes Othello to admit the same spilt subjectivity shown by Shakespeare in his Sonnets. When Ludovico asks of Othello, on entering the stage in act five, “where is this rash and most unfortunate man” (V,ii,321), Othello states “that’s he that was Othello, here I am” (V.ii.320). The two sides of Othello’s subjectivity are thus demonstrated, and moreover, the disjunction of Othello’s person is shown to have occurred after that break in his representation of Desdemona as faithful, namely the moment at which she is called a whore. Here, as in the Sonnets, the emotional effects of how the signification of desire can split a subject can be filly felt; for Shakespeare desire is frustrated by the very act of enunciation, whereas Othello struggles with the way his desire for Desdemona’s fidelity is represented to him. For Othello, the split occurs with the introduction of a defamatory word into his vocabulary for describing Desdemona, such is the force of signification in the construction, or in this case destruction, of a subject.

Moreover, the saintly whiteness of Desdemona can therefore be seen not to mark a difference between her and Othello, but rather indicates the difference of Othello from himself, just as the dark lady is rather an indication of Shakespeare’s own struggle with desire, the dichotomies themselves only supporting the subjects” split subjectivities, and demonstrating the effect of the signification of that desire upon the relationship between the characters in Othello, or between art and Artist in the Sonnets. The single signifier upon which Othello’s subjectivity hinges is also analysed to be the cause of Desdemona’s murder by the critic Lisa Jardin, who in her essay “Why should he call her whore: Defamation and Desdemona’s case,” argues that “a historical reading” of Othello would suggest that “substantial defamation” is the “crux of the plot of Othello” and that crucially, “once substantial defamation stands against Desdemona, Othello murders her for adultary.”38 In order to further demonstrate the effects of language on desire, and demonstrate the movement of desire in art, I will delineate how Jardin’s methodology is itself a further example of precisely that movement.

Desire and Historicism

Jardin’s methodology involves reading seventeenth-century Durham defamation and Ecclesiastical records alongside certain scenes in Othello in order to re-inscribe a sense of female historical agency into the text. Jardin does this by showing that, historically, the “intersection of a set of social relationships and social expectations” present in a defamation hearing in a court of law, which define historical agency for Jardin, are mimetically represented in the text of Othello. This is not to say, as Jardin attests, that the “shared textual conventions of a period are to be mistaken for Renaissance subjectivity” (p.21). Desdemona is not to be taken as a representation tout coeur of a woman being threatened with defamation, rather, Jardin would have it that it is necessary to distinguish within the text between “an offensive remark or gesture” (p.26) from an “indictable offence” (p.26), which, as she shows in delineating the defamation records themselves, is an essential part of Early modern social relations. In this way, to re-instate some historical agency would be to read for the “intersection of a set of social conventions and relations” (p.29), rather than precise mimetic representation of historical events within a text, at which point, presumably, “historical agency” would be evinced. In terms of the play itself defamation occurs as an indicator of historical agency when the accusations themselves are made public, that is to say “it matters where and when she is” not just that she is defamed. This occurs according to Jardin twice in act four,” which invites direct comparison with the cases in the Durham records” (p.29).

There is a manifest contradiction here, not simply in the case of Jardin’s conception of agent, but more importantly in her treatment of the distinction between “literary” and “historical text.” For, as Jardin has stated, reading Desdemona as an actual representation of a woman accused of adultery would be incorrect because that would be to confuse textual conventions shared between literary and historical texts as conferring some sort of historical reality upon Desdemona’s fate in Othello. By then continuing in her analysis to state precisely those historical conventions which constitute defamation and then read them into the text of Othello, entirely defeats her purpose. Jardin seems to be arguing that the text does in fact represent lived historical relations, but not in a mimetic sense, rather, in the way the text is constructed. Emilia speaks the lines Jardin refers to specifically. She questions:

Why should he call her whore? Who keeps her/company

What pace? What time? What form? What likelihood. (V,iv,154-7)

As these lines are spoken in a public context, that is “the verbal has become an event in the community” (p.29) they demonstrate, for Jardin, the way in which the textual reconstruction rather than representation of lived historical circumstances qualifies these lines as the point at which historical agency can be read into the text as a dynamic relationship between those directly involved and the “community as a whole.” However, one text is still reconstructed in terms of the other. There is, I would argue, no point of commensuration between the historical defamation records and the literary text which “reconstructs,” and this simply becomes another word for “presents in a different medium,” them. That is to say, there is no point at which a literary texts becomes historical to the point where historical agency can be read into both texts in the same way; the literary, even on Jardin’s terms, is a presentation of historical circumstances, whereas a defamation records describe those circumstances themselves.

Moreover, what is evident here is that between Othello and the defamation records there is a mutual reference, namely, the defamation of a woman. However, that which Jardin seems to circumvent is that the senses of each text are entirely different. Othello, as I have shown, is an articulation of the effect of signification upon the movement of desire and the construction of subjectivity, and it is that effect which constitutes the text as poetry. Historical defamation records are afforded a different status to artistic texts, although they can be read in the same way, and Jardin herself does this, by privileging the historical defamation records as providing a reference by which specific passages of Othello can be read, so that the poetry of the play signifies the historical authenticity of the Durham records. There is what I would describe as, in Jardin’s methodology, a hierarchical dichotomisation of the texts based on their status as literary of historical, and the two discourses are crossed at such points as act four of Othello. This linking of discourses reduces exactly the effect of signification, which I have shown to be the mark of the relationship between artist and text, as Seaman does in his reading of Othello’s comparison of Desdemona to chrysolite.

The paradox that arises from Jardin’s methodology is that one can actually trace the very effect she reduces in the composition of her text. I would argue that the desire evinced by Jardin is to discover in Othello a space for historical subjectivity, and she does this precisely by re-defining a literary text in terms of a historical one. In this way literature becomes the metonymy of history and Jardin’s desire is moved between signifiers; that is to say the historical subjectivity she wishes to impart on the female characters in Othello comes to be signified by the historical subjectivity shown in the defamation records. I would assert this is nothing more than the process of artistic sublimation, but exactly by foreclosing the effects of the signifier in poetry and re-opening them in the link between literary and historical text. The signification of Jardin’s desire has moved across the very textual boundaries she relies on and as such her desire deconstructs those boundaries. The relationship between Jardin and her text therefore is like that between Shakespeare and the dark lady, or Othello and Desdemona; desire is shown to be characterised in a chain of signifiers which are linked by the sublimating, metonymical effects of signification. Desire thus functions as the excess, to return to Lacan’s formulation, of signification which when the appetite for satisfaction of the desire is met, or the work of art, or criticism, is produced, the demand for “love,” to use Lacan’s phrasing, remains as the very effect of signification which links art and artist.

In this way the movement of sublimating desire can be represented as the Uroboros:

This mythical animal, which is amongst the oldest symbols used in alchemy, dating back to the “tenth or eleventh century” and is depicted as a circle like a “dragon eating it’s own tail” as Jung describes it,40 comes to allude to the alchemical opus itself as circular, that is, “a symbol uniting all opposites” (p.295). Jardin’s opposition between history and literature, as well as Shakespeare’s and Othello’s struggles with the differences in their split subjectivities, are separated and conjoined again by, as I have shown, the effects of sublimating desire, whereby each pole of the artist’s particular dichotomy are differentiated and then conjoined by the movement of desire, or as I have termed it, signification, in language.

Language and the Presence of Desire.

At the opening to the sixth chapter of The Interpretation of Dreams Freud asks his reader to

suppose I have a puzzle, a rebus, before me: a house with a boat on its roof, then a single letter of the alphabet, then a running figure with his head conjured away, and the like41

This is an example of “dream content” (p.210) which functions as one sort of text that can be interpreted to reveal the “dream thoughts” (p.210), or the latent meaning of the dream as expression of the dreamer’s unconscious. This process, as I have shown, is crucial to Jung’s conceptualisation of individuation, as the integration of two parts of the psyche. In Shakespeare’s case his unconscious desires toward his mistress, I have suggested, are not individuated, that is to say, he has not consciously, or artistically, expressed his desire in terms which seal the split in his subjectivity. In Freud’s terms, the rebus of his desire remains unread. It is crucial to note that the dream interpretation would not involve reading the images such those from the above quotation “according to their referentiality as signs” (p.210), rather, “the correct solution to the rebus can only be reached” if the interpreter “replaces each picture by a word or syllable” and “the words connected in this way,” “can yield the most beautiful and meaningful poetic sentence.” Immediately there is a similarity here between Jardin’s methodology and Freud’s. She takes two different types of text, namely Othello and certain historical documents and interprets the literary work as if it were the “dream content” and the historical document as if it were the “dream thoughts themselves,” the meaning of Othello, like the meaning of the dream, is read in a historical text which functions exactly like Freud’s notion of the unconscious. This is not to say that there is any real parallel between historical documents and the unconscious mind, but the is precise parity between the way Jardin expresses the relationship between art and history, and the way dreams for Freud act as intermediary between the unconscious and conscious mind. To be exact, there is a direct analogy between historical text, literary text and materialist interpretation, on the one hand, and dream thoughts, dream content and dream, respectively, on the other. What I would argue is occurring in Jardin’s text, and the Greenblatt text I analysed earlier, is nothing more than the sublimating effects of desire which function expressly like a dream does for Freud. Moreover, Freud states explicitly, “the dream is a fulfilled wish (p.98)” and the wish of the author in each piece I have shown can be read in the enunciation of the work itself. The lexicon of the Alchemists I have used up to this point as a way of representing the expression of desire, that is to say each one represents an aspect of the unconscious process of the sublimation of desire readable into the relationship between art and artist, or critic and piece of criticism. In the last part of this essay I will show how Shakespeare uses alchemical imagery to complete his own artistic individuation, but first it is necessary to show how the desire can be understood as the creation of presence.

In his third published seminar Lacan discusses the most basic binary opposition, that of day and night. He describes how the phrase “the peace of the evening” is made meaningful because it describes the separation of time in terms of a presence. For Lacan

it’s precisely when we are not listening for it, when it’s outside our field and suddenly hits us from behind, that it assumes its full value, surprised as we are by this more or less endophasic, more or less inspired, expression that comes to us like a murmur from without, a manifestation of discourse insofar as it barely belongs to us, which comes as an echo of what it is that is all of a sudden significant for us in this presence, an utterance such that we don’t know whether it comes from without or from within.42

Thus the creation of a dichotomy is marked by a presence, which is signified by the phrase “the peace of the evening.” The process of individuation as the movement across diametrically opposed boundaries creates this very same presence, and that presence can also be signified, as I have shown, by desire. Desire, as I have previously described, is what remains when the appetite has been satisfied and the demand for love remains, and it thus crosses the boundary between the physical and mental. To return to an image I created earlier, this presence created by difference can also be conceptualised as the stream through which both “currents” of love, to use Freud’s terminology flow, and the presence Shakespeare is concerned with is that of a child.

For the “lovely boy” sonnets express a desire for nothing else than the generation of presence. The opening Sonnet of the sequence is a request that the lovely boy produce progeny “that might bear his memory” (l.4), sonnet three has the rhetorical question “where is she so fair whose uneared womb” would “disdain the tillage of thy husbandary? (l.6-7), and in sonnet ten the lovely boy is remonstrated because he should “deny that” he “bear’st love to any.” The lovely boy has to, for Shakespeare, literally signify something else, he becomes the vehicle for the tenor of Shakespeare’s desire, and Shakespeare’s conception of love becomes, accordingly, elaborately linguistic. Sonnet 116 is emphatic in its definition of love as that which “looks upon tempests and is never shaken” (l.6) or does not “alter when it alteration finds” (l.3), Thus the movement of desire can be seen as synonymous with the creation of presence, and as Shakespeare’s conception of love moves away from the physicality of the lovely boy, when he rarefies love to the point it can withstand the wind on the sea, it is then that he starts to “admit impediments” (l.2).

For as I have shown the movement of sublimated desire crosses dichotomised boundaries in order for full individuation of occur, and the presence generated by the lovely boy, the presence of love no less, meets with the obstacle of the dark lady. The physical act of love itself being termed “a waste of shame” in sonnet 129, “savage, extreme, rude” and “cruel” (l.4) and made “on purpose to make the taker mad (l.8) and “despised straight” (l.5) after being enjoyed, here the temporal nature of physical love directly contrasts with the love of 116, which “alters not with brief hours and weeks (l.11). A contrast has been created, and this very contrast, like Lacan’s example of the dichotomy of day and night, is not yet knitted together like the “subtle knot which makes us man” which John Donne describes in the The Ecstasy.43 In Donne’s poem “all several souls contain” (l.32)

Mixture of things they know not what,

Love these mix’d souls doth mix again,

And makes both one, each this, and that. (ll.33-5)

The intermixing of Shakespeare’s dichotomised conception of love begins in sonnets 44-5 where the poet wishes that the “dull substance” of his “flesh were thought” (l.1) so that he can “jump” both “sea and land” (l.7) and be re-united with his lover “as soon as think the place where he would be” (l.8). Here two elements, earth and water, are used to signify the magnitude of the poets longing, and in the next sonnet “slight air and “purging fire” (l.1) represent his thought and desire, which, “present absent,” his thoughts with his lover and his desire within himself, are “life’s composition itself” (l.9), and the poet’s desire is that they be “recured” (l.9). Here the reintegration of the four elements stands symbolically for the restitution of the poet and his lover, so that reconciliation of oppositions can be bought simply by being able to love. The four elements function here precisely as “dream content” does in relation to “dream thoughts” in Freud’s lexicon, and each element can be taken as a rebus and read as a way of understanding how Shakespeare’s unconscious desire can be signified in the work of art itself.

However, the conjunction between the physical and emotional, or sensual and affective, again to use Freud’s terms is still not yet present, even though desire is at this point conceptualised as a form of reconciling parts of the self. Donne presents the same dichotomy in his poem “Love’s Alchemy,” where he chastises

That loving wretch that swears,

‘Tis not the bodies marry, but the minds,

Which he in her angelic finds,

Would swear as justly, that he hears,

In that day’s rude hoarse minstrelsy, the spheres.

Hope not for mind in women; at their best, &

Sweetness and wit they are, but mummy, possess’d. (ll.17-24)

Here Donne is presenting women as empty vessels in which “mind” does not reside, and that there is no more parity between a bride and an angel than there is between a day’s “minstrelsy” (l.22) and the music of the spheres. This is quite explicitly misogynistic, much more so than anything Shakespeare levels at his mistress, and the poem falters at the same place Shakespeare does over his mistress, and for the same reason, namely because the lady here fails to signify anything other than her body. In a reversal of Shakespeare’s “marriage of true minds” in sonnet 116, Donne states that it is in fact that merely “bodies marry” (l.17). However, the marrying of bodies and minds becomes the same process, because the “rude hoarse” cacophony of the day and the music of the spheres heard at night are opposed because they are signified differently, Donne creates the difference by giving each a different value, the sounds associated with the day are negative and the night positive, he has created meaning by differentiation, and so created the very presence he would like to find in women. The presence created by the dichotomising value judgement, which is a signification of something other than what is present in the explicit meaning of the words themselves is precisely the movement of desire which unites the opposites, that is to say they are united because of their difference, by the act of signification, and the feeling that is produced is that described by Lacan’s phrase “the peace of the evening.” What I mean to assert here is that signification creates the impression of presence, and it is that impression that unites binary oppositions, and ultimately allows individuation to occur. Donne and Shakespeare create that presence by setting up pairs of opposites, the most crucial one being between the lovely boy and the dark lady, or conscious and unconscious, or man and woman, or mind and body, or any dichotomy I’ve discussed thus far, but they refuse to ascribe that presence to the wife or mistress herself.

Except in the last of his sonnets Shakespeare does start ascribing presence. A particular presence that, while not named, is precisely the thing that demonstrates his art as sublimation and individuation.

The “cool well,” “cold valley fountain” and Shakespeare’s Conception of Love

In the last two sonnets of the sequence Shakespeare plays, as Katherine Duncan Jones asserts44 “on a conceit deriving from a six-line epigram by Marianus Scholasticus,” which may have reached Shakespeare in an English translation by Ben Jonson , printed as “part of his projected Book Two of Epigrammes.” This would date the composition of the last two sonnets as prior to 1603, a fact which Jones takes as evidence to support her supposition that the poems are rightly considered a part of the “outrageous misogyny” (p.49) of the sonnets 127 onwards, even though some of the “lovely boy” sonnets “were written as early as 1591-5” (p.59) so it is possible to assume the final two sonnets were written at the same time. At whatever point in time the sonnets were actually composed, the 1609 quarto does indeed starkly separate sequence into a division between “homoerotic thrust” (p.49) and anti-female sentiment. I have deliberately avoided reading the sequence synchronically first and foremost because the relationship between art and artist I have shown to be readable elsewhere than in the historic specificity of when the work was actually composed, and secondly because what is crucial to desire in the sonnets is that the creation of the difference Jones describes is itself the most telling indication of Shakespeare’s individuation.

Sonnets 153 and 154 ostensibly re-enact the same narrative:

Cupid laid by his brand and fell asleep:

A maid of Dian’s this advantage found,

And his love-kindling fire did quickly steep

In a cold valley-fountain of that ground;

Which borrowed from this holy fire of Love,

A dateless lively heat, still to endure,

And grew a seething bath, which yet men prove

Against strange maladies a sovereign cure.

But at my mistress’ eye Love’s brand new-fired,

The boy for trial needs would touch my breast;

I, sick withal, the help of bath desired,

And thither hied, a sad distempered guest,

nbsp; But found no cure, the bath for my help lies

nbsp; Where Cupid got new fire; my mistress’ eyes.

Cupid’s torch, which “rather than a bow and arrow” as Jones attests, is the “more ancient attribute of cupid” (p.422) here represents desire. This is then stolen from cupid by a nymph, and this “maid of Dian’s” (l.2) attempts to quench the fire. The attempt is unsuccessful, as the “cold-valley fountain” simply grows to become “a seething bath,” while torch remains lit. There is undoubtedly humour in the way Shakespeare presents cupids “brand” and the bath which men use as the “soverign cure” “against strange maladies,” as Jones asserts there is an association with hot baths as a “treatment of sexual transmitted disease” (p.153) and a site for “sexual encounters” (p.153), but I would argue that the humour serves a specific purpose. It is a type of gallows humour, whereby, as Freud defines “the ego refuses to be distressed by the provocations of reality, to let itself be compelled to suffer.” The provocation of reality that would be distressing in the sonnet is the unquenchable nature of desire, but instead of reacting negatively to this provocation as he does in the dark lady sonnets, here Shakespeare’s ego “insists that it cannot be affected by the external traumas of the external world; it shows, in fact, that such traumas are no more than occasions for it to gain pleasure.”45 The humour evinced here is thus expressly for the purpose of coming to terms with the paradox of desire. The paradox is simply that the fire of desire remains uncured, even in the water of the “cold valley fountain” (l.4). The two elements, each that should have cancelled the effect of the other in fact perpetuate Shakespeare’s desire, which is left “still to endure” (l.6). The sublimation of Shakespeare’s desire thus encapsulates movement across the conceptual boundary between fire and water, and desire’s defining characteristic, its endurance, is described by Shakespeare.

Furthermore, this endurance of desire is exactly what differentiates it from the demand for satisfaction and demand for love. Shakespeare shows in these final sonnets that the sublimation of desire as it is signified in the suspended paradox of the “seething bath” (l.7) is that which allows him to fully accept his desire, and as such the unconscious struggle of the dark lady sonnets and the overly extenuated concepts of love in the lovely boy sonnets has been foreclosed. Thus sonnet 153 acts as a rebus representing Shakespeare’s individuated psyche.