Susan Howe was born on June 10th, 1937 in Boston, Massachusetts, to the American law professor Mark De Wolfe Howe and the Irish playwright and director Mary Manning. From the very beginning of her artistic career, Howe has felt the necessity to explore history, especially both sides of her family roots, to get a place of her own and not to feel like an outsider moving between countries without belonging to any. Although she first painted, soon she decided to exchange the canvas for paper, as words began to have more importance than drawings within her pictures.

Her thematic election is attractive. She avoids the best-known aspects of history or famous authors and attracts the reader’s attention to lesser-known details, information that is not usually available to the general public. She likes going into libraries among ancient books, and there she obtains names, fragments of texts or even words no longer used and take them as materials for her books. Her attention centers in two places: Ireland and North-America. These areas represent her parents and the way she approaches these sites evidences the relationship she keeps with her parents.

Federalists 10, published in 1987, has passed almost unnoticed by critics, apart from some notes appeared in the magazine The Difficulties. The reasons for this may lie in the enormous difficulties in tracing the origin of most of the information it contains or, more probably, the fact that it is little-known because it was published in small numbers by published by a literary magazine of limited distribution.

However, I consider that this work by Howe contains specific elements which make it deserving of a distinguished place among her books. In the first place, this is the only case in the whole of Howe’s career in which she devotes space to American law and politics. She speaks about American history, economy, hand-made products, art, and religion, but none of the books except for this one mentions political or legislative events.

This book could also be firmly connected to her family history. It is not a coincidence either that Howe´s father, Mark De Wolfe Howe, law professor at Harvard, devoted an essential part of his career to the study of religious freedom in America — and she chooses for this work the title Federalist 10. The name is taken from an article published in November 1787 in the Daily Advertiser by James Madison, one of the key figures in developing American Bill of Rights (Millican 1990: 114). Madison would promote the creation of the First Amendment which gives origin to the establishment of religious freedom and the separation of church and state in the United States. Precisely, in this article, Madison advises against the dangers originated by religious groups or sects when they acquire too much political power. Intimately connected to these two circumstances, this is the book where it is found a description of the most important religious groups living in colonial America together with some relevant facts related to their spread.

In her other works, Howe mentions the Puritans and even in one of her more recent books she includes the Labadist (Soul of the Labadie Tract), but no other references are found to such diverse and not-so-well-known groups. In fact, it could be perceived on the part of Howe a necessity of connecting with her father´s world. Through different interviews, she has always stressed the fact they were not so united as she would like. Probably this work can also be considered an exploration of her American identity and her approach to her father as she says in one of the poems: “unhook my father // his nest is in thick of my work” (Federalist, 14).

Another fact that attracted my attention on this work is the fact that Howe does not usually identify place names in her poetry. She often employs brief description and very seldom names, but on this occasion, it is just the opposite. Almost every place is identified by its proper name. It denotes the necessity Howe has to say she is a familiar place a position she could call home. She even employs the names these places received during colonial times which implies Howe´s interest in introducing herself deeply into American history, into her paternal roots.

My purpose in analyzing this Federalist 10 is to show how this is a unique work within the vast corpus of material produced by Howe. I am going to pay attention to the way she integrates all these elements I mentioned previously in her poetry. For that purpose, I am going to establish three fields of analysis: characters, places, and events paying particular attention within each of these sections to those aspects that are more relevant within this specific book and differentiate it from the rest. I am also going to emphasize the way Howe integrates these thematic lines within her poems as an example of how present-day writers change thematic fields in favor of materials that till this moment were not part of poetry being also this an essential expression of her contemporariness.

Howe does not usually enjoy providing proper names for characters, but instead just prefers using expressions that define them. Occasionally she even makes group references. The reason could be that this gives them a universal extension, creating in the reader the impression that the author knows every detail of the story she is introducing. In Federalist 10 she maintains this pattern with certain exceptions I am going to mention in a moment.

I differentiate here between masculine and feminine figures, as the treatment they receive in this work, compared to others by Howe, is different. Most of the time in Howe´s works, the male characters stand for the patriarchy and keep negative connotations. However, in Federalist 10, male figures acquire a positive presentation though they are very briefly introduced. The people she mentions just stand as representative of the numerous groups of men who were to colonial America as a missionary from different religious groups or sects.

Specifically, in Federalist 10 the male figures are just reduced to two mentions, one of them identified by the names of two Moravian missionaries, and the other only recognized as a “ghost-lieutenant.” Howe is not interested in describing their characteristics or what they look like; she instead looks for a temporal and spatial location of the events she introduces. Apart from choosing specific places, the names of “Senseman and Angerman” connect historically with the Moravian people (Rondthaler and Coates 1847: 63) that spread their actions among the Native-Americans in the second half of the eighteenth century. These two men are the most frequently found in historical records for they took part in an incident that almost killed them. They stand for their group as a reference to the difficulties these people endured while teaching the gospel to Native-Americans. Howe also marks their European origin with specific words such as “hus” or “namen.” It is clear these terms do not exist in English but resemble the German language, which is precisely the one spoken by a significant part of the Moravians (Murtagh 1998: 129).

Concerning the other figure, the “ghost-lieutenant” (Federalist, 15), it is equally evasive. Moravian reject war so there would not be any figure among them that coincides with this one unless the term “lieutenant” is understood as a reference to the position a particular man occupies within his group. This points in the direction of “Gottlob Büttner.” He was a key figure in Shekomeko, “earlier ghost-lieutenant / skin with a hero’s name,” where he dies at the age of twenty-eight years old and, as soon as he dies, the other members abandon the village “Right fact and split sect.” Nowadays there is a monument, “A stone warns the traveler,” placed by the Moravian Historical Society at the location of the old mission.

(…) the first successful Moravian mission to the heathen in North-America, and among the first efforts of a body of men, who, above all others, have distinguished themselves for their missionary zeal, and for the extraordinary success of their missionary labors (Moravian Historical Society 1860: 21).

Feminine characters usually deserve much more attention on the part of Howe. In her attempt to recover women from the silence history has imposed on them Howe is going to devote an essential part of her books to describe those women and her stories, and it happens in Federalist 10, too. In this occasion, she introduces three women who, placed in different contents, have a characteristic in common that Howe considers crucial: they are independent and with the necessary capacities to take control of their lives. These characters are the female hermit, Evese, and Margaret.

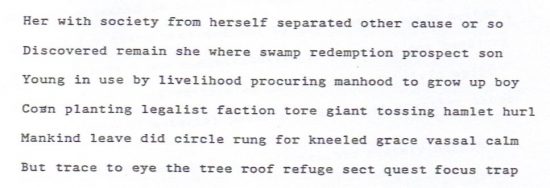

The female hermit is a character inspired by the legends existing among Moravian missionaries and Native-Americans of the area of Pennsylvania (Gunlög 2009: 202; Heckewelder 2007: 200-201). It was said sure Native-American women looking for real contact with Nature and, in an attempt to escape European influence, chose hermit life. There was a specific girl who fled into the forest with her son. Howe seems to inspire herself on this story to compose two of the poems she includes in Federalist 10. These verses attract the reader’s attention to the visual aspect she employs. Although it is a poetic composition, she has chosen a formal pattern that resembles prose. It could be her strategy to attract reader´s attention on them at the same time she introduces a design that could best fit with the story she tells. The narrative of the girl´s life takes the form of tales, a short paragraph placed in the middle of the page.

Another aspect that becomes attractive is the enormous fragmentation these poems contain. There is no punctuation, and the syntactic units do not follow a logical order but seem to have been cut into pieces and then mixed. It uses to be the way Howe transmits confusion, the lack of valuable historical records of the events she is describing. She just takes the information from what people said, from the stories about the existence of a girl like this. In this way, the reader is also left a lot of freedom to interpret the poems. As no sign determines the order or limits of each, syntactical unit, it is only the reader’s decision the one that decides it, opening the possibility of several readings.

At the content level, the author introduces specific clues that allow the reader to determine the origin of the story. She is not too much specific on the accounts she provides but gives two or three clues that trace the source of the story. The first one is in the opening line of this first poem, “Her with society from herself separated other cause or so,” where she alludes to a girl who has abandoned the community for a nonspecific reason.

A most definite clue is at the end of the second poem: “(…) plainly hermit” (Federalist, 7) where Howe makes obvious the girl’s reason to be alone. The author also includes an important detail, the fact the girl was followed by her son, “(…) prospect son / Young in use by livelihood procuring manhood to grow up boy” (Federalist, 7) giving her character the same qualities than that of the girl in the hermit´s legend.

Howe starts her description of the story just when they discover the girl in the forest by some religious figure, probably a missionary. It is deduced from lines like “Discourse remain she where swamp redemption prospect son” (Federalist 6), particularly from the word “redemption” with strong religious connotations. In the following lines the reader gets the impression a whole group of people surrounds the girl and take her back into civilization after her extensive retirement alone in the forest, an interpretation Howe adds to the original story. It is evident from lines like “Corn planting legalist faction tore giant tossing hamlet huge” (Federalist, 6). Here Howe employs all these verbs: “tossing,” “tore” or “hurl” to describe the violence of the act. The girl does not seem to find this return pleasurable, as the final line expresses, “(…) sect quest focus trap” (Federalist, 6), specifically in the words “quest” and “trap.” They were looking for her and prepared her return against her will. This act is done by a group of people, “Mankind leave did circle rung for kneeled grace vassal calm” (Federalist, 6). They are commanded by some religious figure as the reader deduces in the way they join forming a circle or the use of expressions like “vassal” or “kneeled grace” that suggest submission to some superior authority, a missionary or another religious authority the Natives rendered respect.

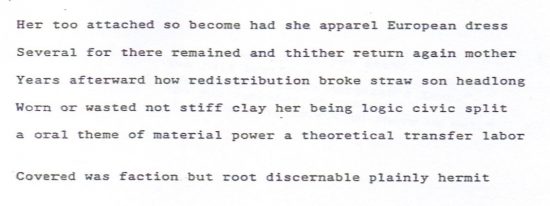

The second poem covers the return of the girl to the place was her home years before, “Several for there remained and thither return mother / Years afterward” (Federalist, 7). Once she has adopted the traditions existing among her people as that of dressing in European style, “Her too attached so become had she apparel European dress” (Federalist, 7). According to the poet, this girl changes the exterior but inside she remains a hermit, “Covered was faction but root discernable plainly hermit” (Federalist, 7).

Evese is another character Howe introduces as part of her portrait of the feminine figure in colonial America. Her name could be inspired in Eve since, like the first woman, this one also has to confront a world entirely new and in constant growth. But the poems Howe dedicates to this woman do not allow the reader to get much information since they are much more fragmented than those I analyzed previously. There are four poems devoted to Evese, but only one of them is not so much fragmented while the rest are just lists of words without links. Obviously, Howe has made it on purpose. All these poems resemble like fragments from a diary, pieces of papers left from a book destroyed by the passing of time or a fire. From the content the reader gets the impression it is a kind of diary or a record of the lives of these people.

One of the first things that the reader deduces from the poems is the fact Evese is married to a man called “Ewyn,” “Evese unied Ewyn belonged” (Federalist 4). Howe employs an expression, “belonged,” she will repeat in the following line with a different tense, “Evese clad led belonging” that tells a lot about the relationship existing between men and women at the time (Mays 2004: 249; Eldrige 1997: 228-240; Applebaum 1996: 261). Women are considered objects to be possessed by men, as these expressions denote. The other word that the author repeats through these poems is the expression “A lamp.” The lamp speaks of these people’s origin. They live in a house; they are probably colonists with a particular social income as they can allow having such a luxury. But they keep the traditional standards. The woman is submitted, she is identified as part of a man’s possession while the rest is unreadable because all this woman’s life is lost in the silence of history. No records, no information kept because she is just a woman and her life is not worth to be saved, or even her belongings were destroyed by fire when they were attacked while fighting against Native-American, people.

The poem that makes an exception to all these is Howe’s interpretation of the story, of the way she wants it to be. The girl becomes “Lady of the Forest,” transforms into a brave girl who moves into the forest to live free from any social constraint, in the style the female hermit did. It is a much more elaborate poem than the previous ones. While the others were just pieces in the center of the page, this one presents a larger size, resembling the patterns Howe uses much more frequently within this book. In this way she establishes the difference between the real and the imaginary, the common existence of a girl and the legend that is born when that girl disappears forever into the forest and her life becomes a legend people tell. Something terrible happens to the girl “Bark leanto / silver in starlight / inhabited by fire.” She runs into the forest, “Lady of the Forest/fear has found you // Fear has found you walking at evening/deepness to be it and to be found,” where she is lost forever. The girl disappears, and her story is part of a legend that will be told once and again, “all that will ever happen/ before and before” (Federalist, 17).

Margaret is the only real character of this group but the one who receive less attention from Howe who just dedicates one poem to her. Howe provides two clues for the reader if s/he wants to get more information on extra-textual sources:

– a note, “Sculls map ¨French referring to the location of this village in a map elaborated by a man called Scull:

“French Margaret“ was a Canadian half-breed and a niece of Madame Montour. Her husband was named “Peter Quebec.” (…) Her place of residence was near the mouth of Lycoming Creek, on the west side, and it appears on Scull’s map of 1759 as “French Margaret’s Town” (Meginness 1892: 30).

– a fragment is taken from John Martin Mack’s diary, which occupies an essential part of the poem, where this Moravian missionary narrates his encounter with Margaret:

August 28- Towards 9 A.M. we came to a small town where Madame Montour’s niece Margaret lives (Newberry) with her family. She welcomed us cordially, led us into the hut, and set before us milk and watermelons. Brother Gruse told her that Mack had come from Bethlehem specially to visit her. “Mother,” said Mack, “do you know me?” “Yes, my child,” she replied, “but I have forgotten where I saw your?” (Meginness 1892: 30).

Howe does not need to provide more information to give a picture of this woman. Just with the details she introduces and the existing historical records Margaret has portrayed an independent woman who has been able to found her town and what is even more critical, this is a place where she establishes the rules. This city is also an excellent example of matriarchy, a practice common among many Native-American groups at the time (Garcia and McManimon 2011: 70; Mann 2006: 53-68).

Few more things are known from Margaret. As in the case of the other two women, Margaret is surrounded by absolute mystery, or at least, anonymity. The author just provides the name and a few details of these women’s lives but their real names or the great deeds they could achieve during their lifetime remain in shadow. The idea Howe transmits is history has been written by men, and they did not record this type of information, so there is a critical gap she makes evident through her poetry.

Two meaningful conclusions can infer from this presentation of characters. In the first place, Howe establishes oppositions between men and women, between patriarchy and matriarchy in these poems. Men, as representatives of Europe, are the ones that impose law and order while they control all religious affairs in the colonies. Women, more connected with America and its new spirit of freedom, provide a new vision of the story in which they exert control upon their own lives, taking their decisions between living on their own as the hermit girl or being surrounded by a community controlled by a woman as Margaret.

Another opposition is manifested between reason and emotion. In these poems, men stand for religion, in order, for a vision of life in which everything is done following a set of rules that cannot alter without provoking distress in the whole community. Women, on their part, move following their principles, that most of the time are not religious. Three women are behaving in very atypical ways: one lives as a hermit, other lives in the forest and there is one who has even founded a village for Native-Americans where everybody, and that includes men, follows the orders she has established. These women live in direct contact with Nature, in perfect equilibrium.

In the second place, another aspect to take into consideration from the characters is the fact Howe is not so much interested in portraying individuals but in giving her picture of the society of the time. The generalization she employs when describing all these characters makes it possible to take them as examples of the way people lived in the colonies. From men, Howe emphasizes their constant attachment to religion, how difficult it is for them to spread their beliefs among Natives, no matter how hard the circumstances can be. From women, on the contrary, Howe pays attention to events that are not from everyday life, that evidence women are not under men control but have a life of their own without losing their place in society.

Concerning places, it is noteworthy that in Federalist 10 Howe introduces a novelty in her poetry when referring to areas. Contrarily to what she usually does in most of her books, here she identifies every location by its name, either present or old one. The reason seems clear. In other occasions, she needed her descriptions general descriptions that could coincide with anyplace in America. So, the reader got the impression her knowledge of those places was extensive. But now she wants to attract the reader’s attention to those sites she keeps a personal connection with. Most of them are in the areas of Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, two places that are quite relevant in the history of her family. Her grand grand-father was the first Episcopalian Bishop of Pennsylvania for several years while her father was born in Massachusetts, a fact that made the whole family proud of. Since this book is like a kind of homage to her father and a search of her American identity, Howe needs to go back to the origins, to the places where that story forged.

But within these two regions, Howe still must be much more specific and choose specific places that could take relevance for her story. The areas she selects are all of them related to a religious group that made its significance within the colonies: the Moravians. Considered by some people as a sect, as heroes by others, they are among the first religious groups that leave Europe with the purpose of spreading the Christian faith within Native-Americans.

Howe is going to pay attention to three specific aspects when referring to all these places: the way people lived in the colonies, the presence of defensive structures and religion.

The way people lived in the colonies: As it is usual in her poetry, Howe does not make extensive descriptions but attracts the reader´s attention to the presence of specific buildings that denote the way people lived such as farms, granaries, etc.

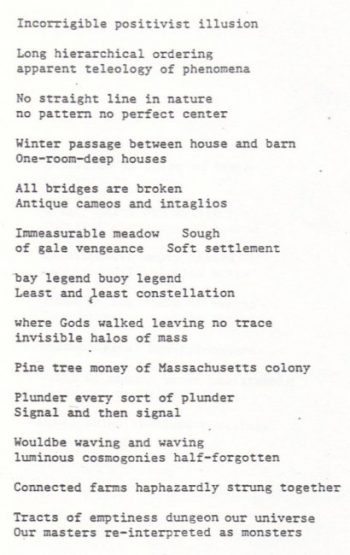

In Federalist 10, Howe just includes few descriptions of the countryside, and none of them belong to the specific places she mentions. When she concentrates the attention of a particular name she centers on other historical events occurred there but rarely in the physical aspect that place presents. In this book, the exception is the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which she dedicates one of her poems too. In fact, most of the information that describes the colonies concentrates on this poem which is not rare because this is an emblematic place for her. Part of her family history originates in this area, so she feels firmly connected with this location and shows in the way she treats it in her poetry.

Howe concentrates the reader’s attention on two characteristics within the poem: the extreme weather colonists support and how it determines their way of living and, on the second place, which activities the colonies perform considering the existing improvements and rests left by the passing of time.

The extreme weather and the hardness of land, covered with all type of plants, “Brian tare thorn nettle,” oblige colonists to adapt buildings to the characteristics of the soil: “No straight line in Nature / no pattern no perfect center.” It makes necessary the edification of a specific set of structures that allow communication between buildings during winter: “Winter passage between horn and barn” (Federalist, 12). Howe also includes a brief description of the houses they build: “one-room-deep houses” (Federalist, 12).

The primary activity that occupies colonists’ lives is farming, “In the brass morning/farms greenbelts badlands.”

The primary economic unit in eighteenth-century America was the farm. Eighty percent or more of the population depended on farming for their livelihood. A majority of colonial farmers owned their land outright, as the property was not a scarce resource and was sold at relatively low prices. (Applebaum 1998: 9)

Farms locate far from each other, “connected farms haphazardly strung together,” being surrounded by enormous fields of land, “In measurable meadow (…) / soft settlement” (Federalist, 12). It makes them vulnerable to receive the attacks from wild animals or even from Native-Americans when they are involved in conflicts. That explains the presence of “ditches and fences” (Federalist, 16) as elements that determine property while serving as a means of defense against undesirable neighbors. Farmers also keep domestic animals as it can be inferred from the presence of “manure” in the following line: “Heaps of manure cover the stubble” (Federalist, 13). Howe also employs this element to show how deep she knows colonial life as it was a custom some farmers used plants to establish them as natural fences for their farms using “manure” to make these fences grow (Farmer’s Magazine 1865: 511).

Howe is so much interested in tracing her roots that while describing the colonies she also refers to the place these people come from Europe. She considers her history forges in the colonies but those who made it possible could not forget their traditions and ideas, which they carry to the New World. She expresses this on two occasions through her poetry, one referring to the objects these people give: “antique cameos and intaglios” (Federalist, 16). In another occasion she alludes to their musical traditions: “Wind roars old ballads” (Federalist, 16), being very popular the ballads they brought from their native countries (Quinn 1951: 563).

The presence of defensive structures manifests this is a period of conflicts, firstly with Native-Americans and later, against the British Empire. The building of forts and other facilities are part of the everyday life in the colonies.

Howe is interested in the relationships existing between Native-Americans and the colonists. Both groups confront for the control of the land, so they use to get involved in different fights from which forts remain a testimony of that past. But Howe does not pay attention to the best-known edifications. She mentions a particular one found in the town of Brownsville known as “Old Fort”: “Defensible woods are clear/ old Fort may be trace” (Federalist, 10), edification built by Native-Americans long before colonists arrived at this territory (Corbly 2011: 116; Parker 1999: 13-14). They were used later by colonists in their defense against the British. Howe wants to transmit how well she knows her country is alluding to less-known details like this while she also manifests Native-Americans kept their internal conflicts before the arrival of Europeans.

Europeans solve their conflicts with Native-Americans signing peace-treaties. Howe alludes to this circumstance in the following lines: “As we stand and as you stand / Two belt brothers” (Federalist, 8). These two lines, apparently unconnected, are part of a bigger text that corresponds to the Peace Treaty signed on 3rd August 1757 by the Governor of Philadelphia and the representatives of several tribes that constituted a group known as the Ten Nations.

Now, at this Day and this time is appointed to meet and confirm a lasting Peace, we, that is, I and my Uncles, as you stand, and you, as you stand in the name of the Great King, three of us standing, we will all look up, and by continuing to observe the Agreements. (…) Now, as I have two Belts, (…), by these Belts, Brothers, in the presence of the Ten Nations, who are witnesses, I lay hold of your hand (…) (Kalter 2006: 275).

One the reader identifies these fragments s/he will be able to associate them with Peace treaties being necessary the use of extra-textual sources.

Religion constitutes one of the most critical motives that carry colonist to the New World. The conflicts they live in their own countries take them to America (Garcia and McManimon 2011:70; Fogleman 2007: 152; Stowell and Wilson 1849: 19-20). But these conflicts are still present in America where religion collapse with economic interests and Native-American traditions and customs. Howe chooses as the protagonist of several poems one of the existing religious groups of the time, precisely one of the less known: the Moravians. As I have already commented, her interest is going to be in those details of American history that are not available to the general public, and this is an excellent example of it. Moravians, as their name indicates, have their origin in the town of Moravia and, after enormous difficulties, move to America where they establish several missions. But they are not among the most popular religious groups of their time (Baird 2009: 250; Lippy and Williams 2010: 1426-1430; Volo and Volo 2006: 60-62).

Howe does not introduce the name of the group in any of the poems but provides the reader specific clues for him/her identify it. Among these clues, it is a fact she gives the name of some of their members such as that of “Senseman” and “Angerman.” Although they are not popular historical figures, the existence of their names makes it possible to trace the relationship with the religious group they belong to. Another important clue is in the different places she mentions within these poems: “Shekomeko,” “Gnadenhütten,” “Freidenshütten (Tents of Peace),” and “Skippack” (Reichel 1858: 98; Volo and Volo 2006: 60-62; Loskiel 1838: 92). These are the names of some of the most important missions Moravians founded in Pennsylvania where colonists not only taught Gospel to Native-Americans but also lived with them in those communities. In fact, “Shekomeko” is considered the first Indian mission church founded in America. Certain names she introduces in some of these poems, “fratrum for natural brethren” (Federalist, 16) also coincide with some of the names the Moravian people receive: “they assumed the general names of Unitas Fratrum, or United Brethren, comprehending all their different divisions under that denomination.” (Proud 1798: 355) One of her poems contains a reference to a specific place in London: “At the bible and sun / in Little Wild Street” (Federalist, 16). This detail apparently unnoticeable corresponds to the location of a bookshop owned by James Hutton, a member of the Moravian group and defender of their cause in England (Podmore 1998: 36).

About events, it is important to say on very few occasions within Howe’s poetry there are allusions to politics or the American legal system. Although her area of interest in American history she has centered her attention on other aspects different from the judicial administration of the county. This book is going to be an exception. Intimately connected with her father, lawyer, and expert in legal areas, Howe devotes part of it to introduce several aspects combined with her father field of knowledge. Without abandoning the historical approach that characterizes her poetry, she centers the attention on those areas she considers crucial for the development of the United States as an independent nation. Going back once more to the colonies, she comments on how the colonies develop their monetary system different from that they initially brought from England; how they grow their legal system with laws that will rule upon all the provinces and the birth of a constitution.

Howe, as it is usual in other books, does not describe the events that take place during a concrete historical period, but she just provides clues leaving the reader to follow them and get the necessary information. She gives lines like “the codification of money” (Federalist, 1), “Pine tree money of Massachusetts Bay colony” (Federalist, 12) or “Paper money and tender acts” (Federalist, 1) where she summarizes how the colonies follow the way to their economic independence.

Massachusetts is the first colony that creates its coins, the “pine tree money.” It characterizes because they have on the head side “a pine tree, symbolic of New England forests” instead of “a portrait of the monarch” (Dobson 2007: 26), is this quite a rebellious act against the Empire.

Paper money and tender acts are also two questions that create conflicts within the colonies. Since they obtained all cash from England, any attempt to create their own money on the part of the local governments attempts against the authority of the Monarchy, and it is not well received.

Something similar happens with tender acts, a line of credits issued to finance the different conflicts colonies get involved and which would redeem with future taxes and Howe reflects it on her poetry in such a particular way.

As the daughter of an American lawyer, Howe is familiar with the legal system of her country and manifests through her poetry that law is one of the most important instruments in the development of any nation: “Land and bits of land / Law and notions of nations” (Federalist, 1). She also uses farming life to describe the legal system of the colonies. She compares citizens with sheep, “The protection of sleep / The protection of sheep” (Federalist, 1) while presents laws as the means to exercise that protection: “Rules are guards and fences” (Federalist, 1).

This image of the sheep is attractive for two reasons. In the first place, the author reminds the reader of the style of life people kept in the colonies, the presence of farms and how they obtain food from the cultivation of the land and the animals they grow. And, in the second place, Howe chooses a specific creature that characterizes by its vulnerability and its necessity of being led by a shepherd, the same that would happen to the new territories that need laws to organize their citizens. These rules are a human invention, “the creation of law” (Federalist, 1), and, as a consequence of that, they are arbitrary, “Fiction of administrative law” (Federalist, 1) as they do not connect to any natural or spiritual principle. They are created by men who want to guide other men, but whose principles are not always well understood by the majority as she expresses in one of her lines: “our fathers reinterpreted as monsters” referring to the American founding fathers, creators of laws and constitution.

Howe also makes emphasis on the First Amendment that determines the possibility different religious groups such as the Moravians grow within the colonies. Precisely, one of its members would declare that:

For two reasons America seemed to him the real home of the ideal Church of the Brethren. First, there was no State Church; and therefore, whatever line he took, he could not be accused of schism. Secondly, there was religious liberty, and consequently, he could work out his ideas without fear of being checked by edits (Hutton 1909: 258).

When speaking about the American Constitution, Howe refers to some of the aspects which provoke greatest debates during the moment of its creation. One of those themes is the connection they establish between “democracy and property” (Federalist, 1). At the time, most laws were inspired by the English legal system. According to it, people were only allowed to vote or be eligible for any public position if they possessed a specific level of “real or personal property” (Federalist, 1). With time, this circumstance would change as not everybody could participate in the democratic system but in its origin it is present, and Howe wants to remind it through her poetry (Stephenson 2004: 63-65; Wulf 2000: 188-190).

There are two other concepts, those of truth and peace, she mentions in the following lines: “Addresses of Peace to Truth / or Truth to Peace” (Federalist, 13) that are going to connect to the First Amendment.

The Court’s understanding of the First Amendments freedoms rural the importance of two themes: civil peace and the quest for truth. Civil order is the object of a government dedicated to the securing of rights and limited by the consent of the governed. It is true that public peace can also be understood as the prevention of strife regardless of the regime.

(…) The acceptance of this view of the quest for truth has secured the substantial freedom of expression and led to increased skepticism about the ascertainment of truth, for philosophy or politics (Dry 2004: 7).

In fact, Federalist 10 can be considered Howe’s interpretation of the First Amendment. These lines appear in the poem that opens the book and serve as an introduction, but the whole of it is a presentation of how people live the religious and political liberties during colonial times. For her father, this was a crucial concept in his life, and she wants to explore it taking as a point of departure to Madison, the creator of the First Amendment, and one of the most popular texts he wrote on this theme: Federalist 10.

Summing up, Howe has a way of making this homage to the First Amendment and, particularly, to her father. Working on fragments, on pieces of information, she obliges the reader to get a firm extra textual knowledge to identify most of the references she includes. In fact, we notice she does not provide one single date in all these poems nor any reference to their historical or geographical location. But the recommendations contained, the characters, the places she mentions or even the political events she includes are the clues given to the reader to discover her discussion goes around America in the colonial period. However, the final result is desirable because she can provide an approach to American history, to the past of this country using contemporary techniques. Her way of writing could remind us of the abstract paintings we see in galleries, but she made these pictures with words instead of drawings. She cuts the information in parts, in small pieces and mixes it all. But once we can identify the pieces, we just need to associate them to get the whole picture, which makes her work attractive because it demands an active role on the part of the reader, which takes his/her place in the construction of meaning.

Bibliography

Applebaum, Herbert A. Colonial Americans at work. Lanham: Univ. Press of America, 1996.

___. The American Work Ethic and the Changing Work Force: A Historical Perspective. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1998.

Baird, Robert. Religion in America. Carlisle, MA: Applewood Books, 2009.

Corbly, Don. The Families of Nancy Ann Lynn Corbly. Raleigh: Lulu.com, 2011.

Dobson, John M. Bulls, Bears, Boom, and Bust: A Historical Encyclopedia of American Business Concepts. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO, 2006.

Dry, Murray. Civil Peace and the Quest for Truth: The First Amendments Freedoms in Political Philosophy and American Constitutionalism. Lanham, M.d.: Lexington Books, 2004.

Fogleman, Aaron Spencer. Jesus is Female: Moravians and the Challenge of Radical Religion in Early America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

Garcia, Venessa and Patrick McManimon. Gendered Justice: Intimate Partner Violence and the Criminal Justice System. Plymouth: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2011.

Gunlög, Maria Fur. A Nation of Women: Gender and Colonial Encounters Among the Delaware Indians. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

Heckewelder, John Gottlieb Ernestus. History, manners, and customs of the Indian nations who once inhabited Pennsylvania and the neighboring states. Westminster, Md.: Heritage Books, 2007.

Howe, Mark Anthony De Wolfe. The Garden and the Wilderness: Religion and Government in American Constitutional History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965.

Howe, Susan. “Federalist 10”. Abacus 30 (November 1987). pp. 1-18.

___. “The Difficulties Interview”. The Difficulties, 3.2 (1989). pp. 17-27

___. Souls of the Labadie Tract. New York: New Directions, 2007.

Hutton, J.E. A History of the Moravian Church. London: Moravian Publisher Office, 1909.

Kalter, Susan, ed. Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania, and the First Nations: The Treaties of 1736-62. Illinois: Board of Trustees, 2006.

Lippy, Charles H. and Peter W. Williams. Encyclopedia of Religion in America. Washington, D.C.: C & M Digital, 2010.

Loskiel, George Henry. The History of the Moravian Mission among the Indians in North America from its Commencement to the Present Time. With a Preliminary Account of the Indians Compiled from Authentic Sources. London: T. Allman, 1848

Madison, James et al. The Federalist. Indianapolis, IN Hackett Publishing Company, 2005. Pp. 48-54.

Meginness, John F., ed. History of Lycoming County Pennsylvania. Chicago, Ill.: Brown, Runk, and Co., Publishers, 1592.

Mann, Barbara Alice. Daughters of Mother Earth: The Wisdom of Native-American Women. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2006.

Mays, Dorothy A. Women in Early America: Struggle, Survival, and Freedom in a New World. Santa Barbara, California: ABC- Clio, 2004.

Meginness, John Franklin. History of Lycoming County, Pennsylvania: including its aboriginal history, the colonial and Revolutionary periods, early settlement and subsequent growth, organization and civil administration, the legal and medical professions, internal improvements, past and present history of Williamsport, manufacturing and lumber interests, religious, educational and social development, geology and agriculture, military record, sketches of boroughs, townships and villages, portraits and biographies of pioneers and representative citizens, etc., etc. Bowie, Md.: Lycoming County Genealogical Society by Heritage Books, 1996.

Millican, Edward. One United People: The Federalist Papers and the National Idea. Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 1990.

Moravian Historical Society. A Memorial of the Dedication of Monuments Erected by the Moravian Historical Society to Mark the Sites of Ancient Missionary Stations in New York and Connecticut. New York: C.B. Richardson, 1860.

Murtagh, William J. Moravian architecture and town planning: Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and other eighteenth-century American settlements. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998.

Parker, Arthur. The Monongahela: River of Dreams, River of Sweat. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State Univ. Press,1999.

Podmore, Colin. The Moravian Church in England, 1729-1760. Oxford: Clarendon, 1998.

Proud, Robert. The History of Pennsylvania: in North America, from the Original Institution and Settlement of that Province, under the First Proprietor and Governor William Penn, 186, till after the Year 1742. Philadelphia: Zachariah Pulson, Jr., 1798.

Quinn, Arthur Hobson. The Literature of the American People: An Historical and Critical Survey. New York: Ardent Media, 1951.

Reichel, William C. A History of the Bethlehem Female Seminary. With a Catalogue of its Pupils. 1785-1858. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1858.

Rondthaler, Edward y Benjamin Hornor Coates. Life of John Heckewelder. Philadelphia: T. Ward, 1847.

Stephenson, Donald Grier. The Right to Vote: Rights and Liberties under the Law. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2004.

Stowell, William Hendry, and Daniel Wilson. History of the Puritans in England: and the Pilgrim Fathers. New York: Robert Center & Brothers, 1849.

The Farmer´s Magazine. Volume 27. London: Rogerson and Tuxford, 1865.

Volo, James M., and Dorothy Denneen Volo. Family Life in 17th and 18th Century America. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc., 2006.

Wulf, Karin A. Not all Wives: Women of Colonial Philadelphia. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2000.

Leave a Reply