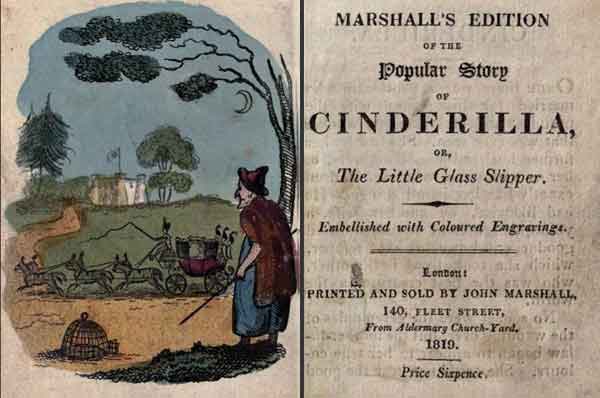

In the tale by Charles Perrault published in Paris in 1697, Cinderella watches her two stepsisters depart for the ball, then bursts into tears. Her godmother, who happens to be a fairy, says, “You wish you could go to the ball, n’est-ce pas?” Together, they a change a pumpkin into a coach, six mice into horses, a rat into a coachman, and six lizards into footmen. At the touch of the wand, the girl’s “wretched clothes” become “a dress made of cloth of gold and silver bedecked with precious stones.” Finally, the godmother gives Cinderella “a pair of glass slippers, the prettiest in the world.”

Like the godmother herself, the glass slippers spring from nowhere, and that difference is significant. At midnight, the coach, horses, attendants, and dress all change back to what they were, but the glass slippers remain. Cinderella loses one on the second night of the ball. Running after her, the prince retrieves it, and it serves as proof of the girl’s identity. To underscore its importance, Perrault calls the tale Cendrillon, ou la petite pantoufle de verre.

For over three centuries, most of us have accepted the notion that glass is a suitable material for ladies’ footwear. Yet a moment’s reflection suggests that glass would break under the weight of even the slenderest maiden. Balzac in his Études philosophiques sur Catherine de Médicis, writes: “Cinderella’s celebrated slipper, without doubt made of squirrel fur, is presented as being of glass.”

In French, the archaic word for squirrel fur is vair, which sounds the same as verre. Littré and others have agreed with Balzac, but Gilbert Rouger quotes P. Delarue in the Garnier edition of Contes de Perrault:

when he wrote verre, Perrault merely conformed to the tradition as given, for the slipper of glass or crystal is attested not only in the tale of Cinderella, but in other tales gathered from Catalonia, Scotland, and Ireland, in versions where one cannot admit an influence from Perrault.

The text is unequivocal. Moreover, a slipper made of fur would stretch, and therefore it would fit a number of feet. The glass slipper is inelastic: it will fit only one person. Near the end of the tale, princesses, duchesses, the whole court, and the two stepsisters cannot force their feet into the slipper. A “gentleman” sent by the prince “made Cinderella sit, and bringing the slipper to her little foot, he saw that it went on easily, and that it fit like wax.” Wax is used to mold things like false teeth and keys, things that demand a close fit. The heroine is marked by her dainty foot size, like the princess who is bruised by a pea placed under several mattresses.

Though Perrault does not say so, those feet are clean and nice to look at through the clear glass. Cinderella does not have bunions, crooked toes, or calluses. As she washes dishes, sweeps the stair, and cleans the bedrooms—the household chores she performs without complaint—does she go barefoot? Does she wear sabots, the wooden clogs of a peasant? To speculate further, is she beautiful from head to toe because she is natural?

Illustrations of the glass slipper show a high-heeled shoe, clear and gleaming, a lovely object to match its description as “the prettiest in the world.” It suggests the nineteenth-century custom of a male lover who drinks champagne from the adored woman’s shoe. In French as in English, “a glass” can mean a vessel to drink from. In one sense, then, the glass slipper is like a goblet, a jewel, an accessory worthy of the “cloth of gold and silver bedecked with precious stones.” In the Grimm version of the tale, the shoe is golden, and in The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy sports a pair of “ruby slippers.” One could go on. Glass in the context of 1697 is rare and costly.

Exciting though it is to imagine a sip of sparkling wine from Cinderella’s glass slipper, or to delve into the subject of fashion as a fetish, which is to say a symbolic substitute for the lady herself, a theme that is not so much latent as glaringly obvious in this tale, the text has pantoufle, which can only mean slipper, in the sense of an open-heel shoe or mule. The French word for shoe is chaussure or soulier.

The ball is a formal affair that demands one’s finest shoes. In Perrault’s time at the court of Louis XIV, aristocratic dancers of both sexes wore high heels. A century later, dancers donned pumps made of thin, soft leather, flimsy things that a single night of dancing could wear to pieces. Ballet dancers today wear satin slippers, equally perishable. Yet a proper appreciation for historical costume allows Cinderella to dance in style. The king cannot take his eyes off her. He says to the queen, “that for a long time he had not seen such a beautiful and lovable person.”

How can the glass slipper be at one and the same time a fashionable shoe, a sloppy slip-on meant for comfort at home, and a rigid object that snugly fits the smallest foot in the land?

The tale never uses the word “magic.” The glass slipper is inert, mineral, an inanimate thing. Likewise, the fairy godmother’s wand is simply a baguette, a stick. She pronounces no spells, and the verb for her marvelous transmutations is only changer. Perrault employs a simple vocabulary and grammar not far removed from everyday speech. His characters do the same. They and the settings they inhabit are almost nondescript. An adjective like “magnificent” or “ugly” is all he provides. What he does point out is the exception, the unique feature, and the glass slipper is certainly that.

I wanted to say it is one of a kind, but in fact it belongs to a pair. Twins, doubles, and pairs have a special meaning in tales, just as they are remarkable when they occur in real life. The mirror symmetry of a pair is uncanny. An exact likeness defies probability. Is a pair a whole of which each item is half? Which of the two is the original, and which is the copy? The riddle is insoluble.

In this case, the pair is also essential to the plot. Cinderella leaves the ball “so promptly that she had let fall one of her little glass slippers.” The verb here is laisser tomber. She does not lose the slipper, which would be the verb perdre, though Perrault implies an accident. Does she let it fall deliberately? Does the slipper have a will of its own, a predestined purpose which causes it to drop, like a hint for the prince to pick up? One of a pair, the slipper seeks its mate, just as the prince seeks his. That was the reason for the ball in the first place, to parade all the eligible “persons of quality” for his inspection as possible brides.

The slipper the prince finds is quite strange, though. It is made of glass. Perhaps he did not notice before, enchanted by Cinderella’s gorgeous dress and personal beauty. Perrault does not take us into the prince’s thoughts, but reports only his announcement that “he would marry her whose foot was the exact size of the slipper.” Like us, the prince takes the glass slipper for granted, a fact of life. He dispenses with analysis and even with emotion. Instead, in the best tradition of princes, he acts.

Cinderella waits for the right moment, then acts in kind. She “pulled from her pocket the other little slipper which she put on her foot.” There is no dialogue, no side-by-side comparison, only “the astonishment of the two sisters.” In this scene of recognition, why substitute the “gentleman” for the prince? Wouldn’t the climax be more effective with the lovers face to face?

Perrault is the master, and we follow where he leads. Here, the two stepsisters at last see Cinderella for who she is. They too take immediate action: they “threw themselves at her feet to ask pardon.” This is social realism, not some mystical awakening. The power relation is now reversed, and they do the prudent thing. The gentleman is also a realistic touch, as he does the prince’s menial work. In any case, the prince has already glimpsed the truth and made his decision. In this scene, as it would not be with him in the room, the glass slipper is the center of attention.

Glass has become common and inexpensive, but it still retains a curious ambiguity. It is not exactly a solid, but a super-cooled liquid that flows, however slowly. It has no internal crystalline structure. It resembles ice but does not melt in sunlight. Still, under certain conditions of light, a sheet of glass such as a windowpane can disappear, utterly transparent. Glass has volume and mass, but it seems to deny the laws of physics. It is both real and immaterial, the perfect material for a slipper that is simultaneously a haute couture accessory, a loose-fitting article of undress, and the mold of one desired foot.

The glass slipper, then, is impossible. It looks real enough, but it behaves in a magical way. Tales contain many such objects: the jar of oil that never runs dry, the ring that grants wishes, and the cloak that makes the wearer invisible. In Grimm’s tale of “The Knapsack, the Hat, and the Horn” all three objects perform wonders for the hero, and for good measure a napkin covers itself with a feast on command. What distinguishes the glass slipper is a certain sleight of hand, an indirect approach to miracles. Like Perrault himself, the glass slipper is subtle. It works through others.

The tale might be a parable about good government, the hidden hand of benevolent rule, the secret tool to accomplish what everyone says can’t be done. Perrault, after all, served in the royal finance ministry under Colbert. He wielded influence, and he understood intrigue. The glass slipper is the transparent means to an end.

In the plane of fiction, the slipper is a gift, and the giver is supernatural. In the Grimm version of the tale, the fairy godmother is the ghost of Cinderella’s mother, a saint who comes to her aid. Would it be wrong to see this spiritual character, who often appears to the hero or heroine, as a projection of his or her mind?

We all engage in dialogue with ourselves. Tellers of tales correctly make a drama of this dialogue. They show us the better angel who talks inside our heads. Cinderella fetches the pumpkin from the garden for the coach. She catches the mice, the rat, and the lizards. She has already ironed her stepsisters’ clothes and arranged their hair for the ball. She is a capable girl who has “good taste.” Far from being a passive victim of oppression, she says what she wants aloud, and she goes out to get it.

Perrault ends his tales with a moralité in verse, often followed by an autre moralité. The two that conclude the Cinderella tale point the moral in these terms. Beauty is not enough. A girl needs bonne grâce—the phrase occurs twice in the first moralité. What is this good grace? The autre moralité says that wit, courage, birth, good sense, and other talents are vain things unless you have a godfather or godmother “to make them count.”

A godparent is a sponsor at baptism, and he or she ought to sponsor the child through life. If we read the text literally, then the second moral cancels the first. The government official states that you must have gifts and a patron to intercede on your behalf. In this contest of naïve virtue and cynical string-pulling, where did the glass slipper go?

With the possible exception of Riquet à la houppe, Perrault did not invent his tales. He took folk tales that he seems to have heard, cast them in a literary mold, and polished the result. I take the moralités as part of the polish, the finishing touch. While they claim to explain the preceding story, they add a sheen of abstraction, which a fairy tale avoids like the plague. While making a pretense of logic and clarity, they dazzle and distract. They are cut from the same cloth as the dialogue between the hero and heroine of Riquet à la houppe. Polite, rational, and delightfully absurd, the lovers argue to convince no one. Here, with a wink, Perrault warns us to look sharp. The glass slipper has vanished.

Leave a Reply