Milkman

Since my car fell apart in November 2018 I’ve been commuting 12 miles to work without one, via crumbling New Jersey, USA public transportation infrastructure. The roughest parts of my commute happen on foot. I’ve picked up poison ivy trekking the side of a highway without sidewalks. The buses run infrequently and follow their schedule only erratically, so I am often stranded outside, without even a bus shelter around me, in brutal winds or freezing rain. The street harassment from men is constant, though it never gets any easier to endure.

Just last week a stump of a man I hadn’t even noticed on the bus scooched into my seat, motioned for me to take my headphones out, then asked how old I was. (Huh?) The only answer I gave was, “No.” He apologized for bothering me but lingered too long in the aisle, sizing me up and down once more before he left me alone at last. I couldn’t relax for the rest of the trip—would he come bother me again? Were there other men lurking, hoping to steal my attention, or worse?

To be unwillingly hit on in public is to be derailed and distracted until safe again at home. Incidents like this happen every day on my route to or from work.

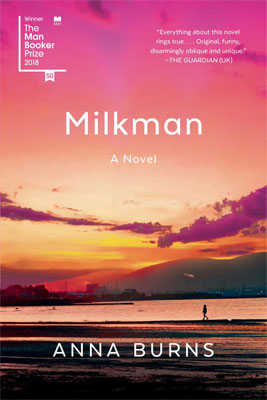

The only bright spot has been listening to the 14-hour audiobook of Milkman by Anna Burns, masterfully read by Northern Irish theatre actress Bríd Brennan, during the commute. The confessions and foibles of this first-person narrative help me move through the danger, trauma and inherent sexism keeping a distressed society in motion (hers and mine).

The only bright spot has been listening to the 14-hour audiobook of Milkman by Anna Burns, masterfully read by Northern Irish theatre actress Bríd Brennan, during the commute. The confessions and foibles of this first-person narrative help me move through the danger, trauma and inherent sexism keeping a distressed society in motion (hers and mine).

Milkman, the 2018 winner of the Booker Prize, delves into one young woman’s mind to examine the constraints put on women by society-at-large. Told through a conversational style, Anna Burns captures a culture and collective psyche, much in the style of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels or the My Struggle series by Karl Ove Knausgaard.

This novel offers a deep look into the life of one unnamed 18-year-old woman as she comes of age in Belfast during the 1970s. The city and country are never explicitly named, but the backdrop of the Northern Irish “Troubles” are made clear over time. She has lost family members to car bombs and lives in fear of both loyalist soldiers and getting caught in the crosshairs of renouncer violence.

Life changes for our protagonist when an older man begins following her around in public, making it clear he has tracked her routine as well as the lives of her family members. She never accepts his advances, but talk spreads fast around her neighborhood that this stranger, known as The Milkman, is her illicit lover.

The Court of Public Opinion

The narrator of Milkman is blamed for her own harassment. Her mother refuses to believe her when she explains that she is being stalked by this older man but never travels with or encourages him. Her mother has heard reports of her riding around in his van, so she sides with the neighbors, doubting the word of her own daughter.

In this way the Milkman controls her, using the gossip of her community as a weapon. He is not above blackmail; he lists off the marital status or residence of her large family, without leveling an explicit threat but making her uncomfortable all the same. He suggests that he knows how to locate her and everyone close to her, leaving her to guess at his intentions.

In Milkman, gossipy neighbors blame our protagonist for being stalked. They demand things like, Why are you taking walks or foreign language classes downtown? Why aren’t you married? Her existence is the problem, not men making threats and leering. If only she gave up reading during long walks or any hint of identity and independence, then she would be safe.

And the greatest irony of all: this older man is probably not even a milkman! We never know who started this assumption or why it spread, but this is the name he is given and it sticks. The prattle of her neighbors becomes more real than fact, trapping our narrator in this confused reality.

This not-milkman has probably figured out that if he spreads the rumor that they are lovers, she will be treated as if this is so, thus coercing her to become his lover in the end. She is already living the consequences of being the lover of a married older man—so why should she resist this fate?

I am in my 30s and I have never had any savings. Each month I pay out more to student lenders than I do in rent. When utility bills are higher than usual or an emergency like a $1,000 car repair happens, I have had to tap into a credit line through the bank. Until a month when two emergencies happened, the credit line was maxed and the bills were due. I paid them all on time then had no food at home for a week.

The nearest open food pantry was a mile away. I flushed and fought the urge to turn around and run home as I marched myself to the church rectory, where I was to register as a new client.

“Hey, baby!” came the catcall from across the street. Even in this darkest and most vulnerable of moments, some random man felt entitled to my attention.

And just like that, I deferred to a script deeply ingrained. Any look in his direction would be celebrated with his cackle. I frowned and kept my gaze ahead, somewhere vague. When I looked down I saw stretchy black pants I picked up at a “free store” years ago. What betrayed me as a baby worth bothering in public? Short hair pinned back with a headband? What about me peeked out from amorphous clothes, demanding attention? Had I brought this on myself, wearing a frayed hoodie and no makeup, while I marched myself to a food pantry in a hungry daze?

I grit my teeth and let the disgust roll over me—of my own body. For standing out and calling attention to itself. For needing regular infusions of food, which I so often can’t afford to give it. Sweat sprouted across my forehead as I walked faster to avoid the harasser and fought back the shame and self-blame.

Waiting on a line gave me time to gather some composure. A bald septuagenarian smiled at me while I wiped tears from my face, then passed him my driver’s license to verify my address. Genial pantry food staff handed over four canvas bags of cans and packets of food, asking my preferences—do I like dairy? Is spicy soup OK? They stacked the yogurt and instant rice and protein bars until those navy grocery bags brimmed with necessary but heavy sustenance. My arms were screaming from the weight of the packaged food. My neck would be sore for the next three days.

I was in luck—I only had to wait 20 minutes for the next bus to pass. I found a sunny corner to wait on.

A man approached the bus stop and my heart sank, because he made eye contact with me and immediately threatened gestures with his hands—a karate chop, a jab with a fist, fingers slicing a throat. I had this script in my mind as well: this man was clearly unwell, perhaps strung out, or missing his medication. An orange crust caked his too-blue eyes, which never left me. He pantomimed that he was about to touch me, but stopped himself just short of contact.

I wanted to run—or better yet, drive away. But the food pantry bags kept me so anchored down that moving again seemed impossible. I stared off into the distance and willed the bus to arrive.

How far would I go to protect my own being, or my food? My heart thumped in my ears as I nursed violent thoughts, of hurting the stranger in public who threatened me, to make sure I always stay safe.

Yes, I struggle to be compassionate toward folks who are homeless or struggling with mental health issues and/or addiction. But I will never be convinced I have to extend compassion toward street harassers. They make me hate myself so much more than I could ever hate them—but I reserve my right to disdain them all the same. Most of all because they keep me in a constant state of fear, which is the source of my revenge fantasies and ugly thoughts about them. I feel the fear warping me, causing me to rust from the inside out. Every time I leave the house and risk being injured by a man, I corrode a little more.

The bus arrived and I didn’t hurt anyone, not even myself.

In Milkman, the narrator is guilty in the eyes of her family, friends and community for acting strangely in public, so any attention from men during her long walks is her own fault. The rules are so ingrained, no one can question them. Or if one tries to question them, that person is seen as a trouble-maker and made an outcast. Our narrator learns the hard way what the expectations of her and how she will be tried in the court of public opinion. She will be found guilty with no chance at proven innocence.

I don’t know how to deal with street harassment and I never have. I can remember when this force entered my life. The summer after 8th grade graduation, grown men and security guards started approaching me in the mall, asking me my age and where I was going. “I’m thirteen!” I sputtered, prickly flares of shame around my collarbone. I didn’t want their attention, felt embarrassed at being noticed, when they replied, “You don’t LOOK thirteen.” I absolutely picked up their implications: Somehow, I had led them on. By simply existing and shopping with friends and being in public, I’d been on display for them, inviting their advances. I would hold my breath and hide out deep inside one store or another, willing these adult men to leave the premises.

Attending a regional Catholic high school meant having to wait around for a school bus or a city bus on high-traffic street corners. In a school-girl uniform. In the age of the “Hit Me Baby One More Time” video. Men leaned out of car windows to blow kisses or call names. Construction workers snarled in my direction. For the rest of each day I never quite got over the startle, my heart’s skipped beat. But at a certain point I did start telling men to Fuck Off.

This had become such a routine part of my adolescence that at 16, my Lenten resolution was taking a break from flipping off the men who shouted at me from car windows. I was too humiliated to admit this resolution to teachers or the school chaplain. I kept this particular devotion in secret.

That year I learned not responding felt worse—my silence felt as if I accepted the attention gleefully, as if it was what I’d wanted all along. I simmered and pretended I couldn’t hear men’s comments, though they haunted me for the rest of the school day. I can recall some of them now, 20 years later. After 40 days I decided that telling creeps to Fuck Off actually wasn’t a sin. I screamed things back, unleashing the anger, from below firetruck red bottle-dyed hair, from deep inside my navy-blue plaid skirt and uniform polo.

I screamed back that I had STIs with graphic specificity. (A choice I wouldn’t make now—STIs aren’t funny.) One summer my best friend and I anointed ourselves renegades as we drove around screaming the phrases at random men that were first shouted at us. “WHORES!” we called to two vaguely masculine figures who, we realized too late, were a father and son fishing at a pond.

I’ve done so many wrong things to try to deal with the fucked-up actions of men in public. None of them help. I still don’t know what’s right.

The Jacket

My jacket works like a bullseye. With the hood up from the sweatshirt underneath and nondescript black jeans, I could almost slip past visibility on the street. But when my former (black) jacket was reduced to shreds after years of use, I combined a few online rebate gift cards to place a bid on a powder blue Columbia puffy winter jacket, on sale. I’d never known eBay had a clearance rack. It is waterproof and warm, by all accounts a practical choice. When I got this jacket, I still had a car. Once the Chevy warmed up in the mornings I would overheat and wiggle out, tossing it onto the passenger seat during a red light.

Now this coat, my only coat (and I am out of rebate gift cards), marks me as weirdo the moment I walk out my door. As white. Worst of all, as woman.

The coat has helped me map the worst places to be a woman across three counties: Main Street, Asbury Park and worst of all, the Lakewood Bus Terminal.

I will not wait for buses longer than five minutes at the Lakewood Bus Terminal. When unlocked during business hours, the waiting room blares saccharine talk show reruns at a deafening volume. A woman in a powder blue coat cannot stop to look at the monitors. All the seats are taken by the sleeping, writhing, chattering street people, who travel nowhere but have nowhere else to sit and wait for death. When you stand out, you attract attention. You are yelled at for staring, for breathing, for withholding money or food. For being someone else. For being who you are. For wearing a powder blue puffy jacket.

In the foyer, where bus drivers stretch their legs between routes, lies more danger if you find yourself alone. Once when the lobby was locked, I was stuck there with one passenger, a man, and the only presumed employee on premises (he wore a neon green vest at least) bragging about a violent fistfight the previous weekend. He went for the throat, he made him bleed. They laughed.

Just outside the doors, if there are no buses present (and even when they are), the atmosphere is somehow worse. Once in the open air, men stand too close and ask for things—they ask if they can ask you a question. Will you give them something or buy them something, where are you going do you have a boyfriend. They ask and ask and ask and they stare. They get angry when you won’t answer, or give the wrong answer.

The Lakewood Bus Terminal is home to the damned. I will not wait there.

During longer layovers I will walk along the route, pausing at each stop to guess when the next bus will stop there. If I am scheduled to be standing for more than 10 minutes at a stop, I move along. A blue coat is a marker when stuck outdoors at a bus stop as well. When standing at a bus stop, men pull over and order me to get in their cars. They do not ask and they do not offer. They wave and say, “Get in.” I don’t. I won’t. But they pull over, stop and command. Pull over to insist. One drives away. Another stops. They ask in English or in Spanish. They are white and Black and Guatemalan and Honduran and Mexican men, they are tweaking or they are high or they are drunk or they are just very, very angry that I won’t hop into a passenger seat with a stranger at the wheel.

The bus comes by once every hour or every two hours, sometimes every 90 minutes. It’s a lot of walking. But it would be even more standing to be ordered into a car or wallowing in the inferno of the Lakewood Bus Terminal.

I have never taken a walk down Main Street, Asbury Park without being yelled at by a man. I live in Asbury Park. I take this walk every day. Recently a man on Main Street trailed me for two blocks, my backpack full of groceries and stretching my shoulders as if on a rack, Inquisition-style. Do you hear me sweetheart? He waved his hands in my face but I wouldn’t look at him, I would give him no satisfaction for interrupting my day. I just screamed NO! and he backed off, fell behind me.

It felt good to scream NO! Until it didn’t feel like enough. I wanted to stand there and berate him, tell him I wouldn’t care if he dropped dead in front of me, tell him I hated him and wanted him to die. There is so much I want to yell back at men but I am too afraid of the way it could escalate into violence. I don’t want to get beaten or abducted on a street in New Jersey and I know this is possible in the places I live and travel through. (I invite you to search “Lakewood, NJ” in Google News if you’d like to see more.)

At the start of my commute home from work, in Toms River, I listened to the narrator of Milkman describe carrying the head of a dead cat home from a field, where it had been killed like vermin for being associated with witchcraft and the feminine.

The Milkman finds the narrator, even here, in a dead patch of earth that had been bombed by Nazis three decades prior and was likely wired by bombs from either side of the conflict at the time she stood there. It is now clear to our narrator that this “milkman” is a paramilitary resister to British rule of Northern Ireland, feared by some and admired by others, including her own Catholic, resistance-sympathizing family.

This gives the Milkman another layer of power over her, and he makes it plain that he will continue to stalk and approach her. He acts as though it is only a matter of time until this narrator is his lover, as she is already presumed to be. His power over her in public, through reputation if not sheer brute force, is overwhelming and undeniable. Nonsensical as it is, our narrator continues to clutch the dead and decaying head of a cat, insisting on giving it a proper burial, refusing to let it go discarded and disrespected after its senseless death.

Over the din of my headphones I watched a man pull to the side off the road and roll down the passenger window. He told me to get in. I said no as I always do. But then, after he’d accelerated away, I was overcome by tears. After seven hours of sobbing, I had to admit that this was a panic attack—not something I am prone to. Or at least, it had not been up until that point.

I’m tired. I’m tired of being tired and scared all the time. My own hands cling, in all their futility, to the belief that if I just keep working and paying, I’ll be out of debt and secure. I won’t have to live off expired dairy from the food pantry any more. I can shield myself in another car I own, protected from the advances of men on the street.

But that thing I cling to is decomposing in my hands.