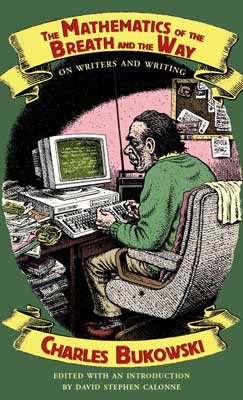

The Mathematics of the Breath and the Way: On Writers and Writing by Charles Bukowski. Edited by David Stephen Calonne / City Lights Books / 978-0-87286-759-8 / 2018

I kind of don’t know how they keep coming, but Charles Bukowski was such a prolific writer, and perhaps so disorganized, that posthumous collections of both prose and poetry continue to trickle out, 24 years after his death. I’m not convinced that the latest, The Mathematics of the Breath and the Way: On Writers and Writing, from City Lights Books, is the last. For which I’m grateful. There has been no writer as influential on my writing and on how I live my life than Charles Bukowski, and his irreverence and critique of the American Dream has continued to be a joy for most of my adult life.

Mathematics is the fifth posthumous collection of Bukowski’s prose from City Lights Books. I’m not sure on why or how City Lights gets the rights to these works while his posthumous poetry has continued to come out under Ecco Press, a subsidiary of HarperCollins. Bukowski’s original publisher John Martin, of Black Sparrow Press, sold the rights when he retired. I guess maybe the answer is that Bukowski’s prose, especially this obscure stuff, was always a little bit both edgier and sometimes sillier: The majority of the essays and stories (sometimes it’s hard to distinguish the difference) are from Bukowki’s Notes of a Dirty Old Man column which he published, weekly, for years with entertainment rags in LA like Open City and LA Free Press. Bukowski apparently never kept track of these columns, so if someone (like this collection’s editor, David Stephen Collonne) can just manage to find old copies, he’s halfway to a collection.

Mathematics is the fifth posthumous collection of Bukowski’s prose from City Lights Books. I’m not sure on why or how City Lights gets the rights to these works while his posthumous poetry has continued to come out under Ecco Press, a subsidiary of HarperCollins. Bukowski’s original publisher John Martin, of Black Sparrow Press, sold the rights when he retired. I guess maybe the answer is that Bukowski’s prose, especially this obscure stuff, was always a little bit both edgier and sometimes sillier: The majority of the essays and stories (sometimes it’s hard to distinguish the difference) are from Bukowki’s Notes of a Dirty Old Man column which he published, weekly, for years with entertainment rags in LA like Open City and LA Free Press. Bukowski apparently never kept track of these columns, so if someone (like this collection’s editor, David Stephen Collonne) can just manage to find old copies, he’s halfway to a collection.

As I said in my review of the last posthumous City Lights collection, The Bell Tolls For No One, I’m not sure this is the best book to try Bukowski for the first time. For the hardcore fan, like me, there are the expected bits of Bukowski wisdom and humor, and the overall sense of joy at least I get. There is not that much critique of the American way and capitalism, which is the core of his biggest works. Most of the essays and stories based on his life here (which is most of them) come from his middle period when he was employed by the Post Office, though a couple of the Notes columns are basically dry runs for chapters that appeared in his best novel, Women. Bukowski wrote about certain scenes and women over and over, in short stories, poems, and novels, each of them familiar, but with a different take.

The difference here, which might be of interest to some not-so-gung-ho Bukowski readers is that the style of these stories contains a bit more description of emotion. His later, greater, middle period had him adopting more of the Hemingway iceberg style: describing the action and dialogue, leaving readers to imagine (and, I would argue, feel more strongly) the emotions. But, if you don’t agree with that, these might appeal, and in any case they both stand on their own and offer a look at how Bukowski was developing as a writer. Bukowski never gave them titles (the Notes of A Dirty Old Man column was only ever called that), although editor David Stephen Colonne, for this edition, has given us informal titles from the first line. The story “I had given up on women” on page 100 is maybe the strongest piece.

But there are just some straight-up short fiction, though again, sometimes they were just titled “Notes of a Dirty Old Man.” I’ve always thought Bukowski was underrated as a short story writer. Check out his stories “The Most Beautiful Woman In Town” and “The Great Zen Wedding” in other collections to see him at his prime. He can get both brutally serious, and zanily surreal, as in with two stories in this collection, “‘Harry,’ said Doug”, from a Notes column, and “Politics and Love”, published in the 70s men’s magazine Oui (which may be another explanation why Ecco doesn’t want to touch this stuff. “‘Harry,’ said Doug” is particularly disturbing and one hopes it’s not an essay).

The subtitle of the collection, “On Writers and Writing” comes in part from the number of book reviews and introductions to other writers’ (out of print) books which Bukowski wrote, and which Calonne has managed to track down. These are the least interesting part of the book, except for Bukowski’s review of Hemingway’s posthumous novel Island In The Stream, which at least is refreshing in its style after reading too many formal reviews in The New Yorker and Harper’s (confession: I want to write reviews for Harper’s). Here, Bukowski writes like he talks for most of the review, or how we imagine he would talk if we were sitting down talking about Hemingway, though then comes this Hemingway-esque final paragraph:

All in all, Hemingway knows his men and his war and his food and his drinks and the wind and the sea and the birds, and how to boat, and he knows his crabs and his wild boars and his dogs and his insects, and he knows his death is coming. He’s weak on his women but most of us are, and his conversations aren’t quite real; they are Hemingway conversations, but once you realize this you can accept them. And there’s free knowledge in the book on all sorts of little things besides making good drinks. Although I don’t care too much for his peanut butter with raw onion sandwiches. Or hanging up a slightly demobilized bird in the kitchen with a piece of string by one leg and finding out later that the big cat got it. 466 pages are many pages and maybe that’s why it’s ten dollar or maybe it’s because it’s the last of Hemingway. I suppose it matters how you feel about Hemingway and how much money you have, or both. No, the book doesn’t make it. Few do. I’d say buy it just to know which way things went. They went that way. And he’s gone now. You know how. And, without lying, let’s not try to be too unkind.

Which is what we might say about this book. And Bukowski.

What makes Mathematics unique from the other two recent posthumous City Lights collections is the collection of interviews with Bukowski at the end. In most other interviews, even and especially the documentaries featuring him, Bukowski tends to ham things up a bit, and/or to be drunk, or hamming up his persona as a drunk, so that we never really get to learn how his mind works, or at least his writing process (though he does talk about that in other pieces of writing, including his fiction. But here, in at least especially two interviews, with literary journals Stonecloud and New York Quarterly, Bukowski seems to be more on the sincere side, or as sincere as Charles Bukowski could ever let himself be. I think it’s because these particular interviews happened just before he broke big, when he had quit his day job and was making his living as an actual writer, around the time of his second novel Factotum, but before his novel Women and before his peak poetry (from Love is a Dog From Hell to War All The Time).

The interviewer brings up Bukowski’s use of “common language” as a rejection of academic or obscurity for the sake of obscurity in poetry, and Bukowski’s qualification still rings true today for spoken word poetry, which claims to be language from the street:

I think I’ve broken through more or less to the common language. But we don’t want to make it too common….It’s kind of like flaunting the street language, instead of using it. I think they gotta calm down a little before they get to it….What you end up with is a lot of clichés and the platitude.

Which may just piss off some people. Bukowski does that, especially if you don’t have a sense of humor. It’s not that he goes out of his way to offend (well…) but he holds an irreverence towards people, most especially himself, which is key and which is what non-Bukowski-ites seem to (willfully?) miss. He’s making fun of the whole human condition. The Mathematics of the Breath and the Way is not Bukowski’s best—how could it be—but for me it’s a good healthy fuck-all-this-bullshit to the depressing shitshow going on right now.