John Digby was born in London in 1938. He began writing Surrealist poetry from the early 1970s. He was influenced by Breton, Eluard, Arp, and Desnos. Although he was living in England, the first publications of his Surrealist poetry was in America during the time that he worked with George Hitchcock on Kayak Magazine in California. Three books of his poetry were published by Anvil Press Poetry in London: The Structure of Bifocal Distance (1974), Sailing away from Night (1978), and To Amuse a Shrinking Sun (1985). These were illustrated with his black and white collages, a medium he has continued to expand from figurative to abstract over the past several decades. Over the years, he was published in Wales, France, Belgium, Germany, Colombia, and Romania. His poetry is included in The Penguin Book of English Surrealism. In England, he was the co-founder of Caligula Books.

John Digby was born in London in 1938. He began writing Surrealist poetry from the early 1970s. He was influenced by Breton, Eluard, Arp, and Desnos. Although he was living in England, the first publications of his Surrealist poetry was in America during the time that he worked with George Hitchcock on Kayak Magazine in California. Three books of his poetry were published by Anvil Press Poetry in London: The Structure of Bifocal Distance (1974), Sailing away from Night (1978), and To Amuse a Shrinking Sun (1985). These were illustrated with his black and white collages, a medium he has continued to expand from figurative to abstract over the past several decades. Over the years, he was published in Wales, France, Belgium, Germany, Colombia, and Romania. His poetry is included in The Penguin Book of English Surrealism. In England, he was the co-founder of Caligula Books.

For the last 38 years, he has lived in Oyster Bay, New York, where he co-founded (with his wife Joan Digby) The Feral Press, which publishes digitally produced limited editions of illustrated booklets of poetry and short fiction. In 2017, the press migrated to New Feral Press. For the past several years, he has been collaborating with Hong Ai Bai on an extensive project publishing books devoted to English improvisations of classical Chinese poetry.

John Digby and Bill Wolak have been friends and collaborators since 1976, when they were first introduced to each other by the poet Nathaniel Tarn.

Bill Wolak: Both your writing and your collage work is filled with a deep love of animals. How did you become so interested in animals?

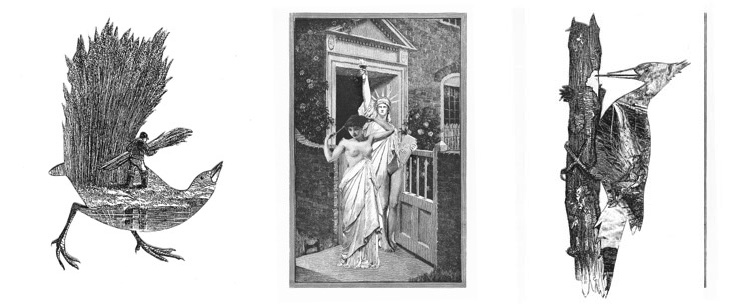

John Digby: My grandfather brought me home a picture book of English birds, so bird books, and later natural history books became a passion for me. I fell in love with the pictures, and he taught me to read using all the descriptions of the birds, their nests, their eggs, and their haunts.

So from an early age, I developed an interest in aviculture—soon I was hunting for books on foreign birds. My interest in birds began to broaden, and this was due to weekly radio broadcasts on ornithology by James Fisher. I believe it was my grandmother who suggested to a friend of the family take me to the zoo for the day. It was there that my “birding” days began. Inside the aviaries, I stood entranced completely rapt in wonderment. By the time I was 14, I became a keeper at the London Zoo.

BW: Isn’t that young to be working in a zoo?

JD: I lied about my age, but my knowledge of birds and natural history got me the job, and, as luck would have it, I found myself working as a keeper in the small bird house. Very early on in my career at the Zoo, there came a policy that the keepers had to attend lectures on all animal, bird, and reptile subjects. Maybe this prompted me years later to enroll in the Working Mens’ College to get myself an education. It was there that I fell in love with poetry.

BW: Which poets did you begin reading around that time?

BW: Which poets did you begin reading around that time?

JD: I was and am still particularly fond of John Milton, William Blake, William Wordsworth, and John Keats. In addition, I enjoyed Matthew Arnold, especially his poems, “The Scholar Gypsy,” “Thrysis” and “Sohrab and Rustam.” Later, I discovered Rimbaud’s “Le Bateau ivre.” Rimbaud’s poetry released my imagination from its constraints.

Next, quite by accident, I discovered the Dadaists. Everything to them was absurd. This feeling that reality was absurd confirmed something that I had sensed since childhood, perhaps because I grew up during the horrors and confusion of the War and because I’m a little dyslexic. Reality always seemed slightly uncanny and inexplicable.

Finally, I began to take an interest in Surrealism. I became fascinated by the idea of Surrealism. I searched out many translations of surreal texts from various European languages. But the one Surrealist whom I believed to be a superior poet was Robert Desnos, whose poems were tinged with superior imagination and an eerie spiritualism.

BW: When you first started writing poetry, what were you attempting?

JD: Writing poetry for me was endeavoring to find my own imagination. However much I failed, I had this “feeling” that at least I was trying!

BW: So how did you begin writing Surrealist poetry?

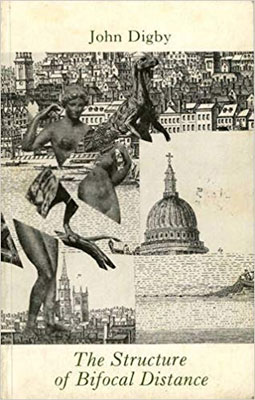

JD: I began by experimenting with dream imagery and various aspects of the absurd. Little by little, I found my niche. Gradually and with a great deal of luck and perspiration, I managed to get my poems accepted in various magazines. I must admit, I did better in America than England, but, nevertheless, I succeeded in publishing in both countries. Then my big break came when Peter Jay, the founder of Anvil Press Poetry, took on my first book of poetry, The Structure of Bifocal Distance, and allowed me to design my own book cover with one of my collages.

JD: I began by experimenting with dream imagery and various aspects of the absurd. Little by little, I found my niche. Gradually and with a great deal of luck and perspiration, I managed to get my poems accepted in various magazines. I must admit, I did better in America than England, but, nevertheless, I succeeded in publishing in both countries. Then my big break came when Peter Jay, the founder of Anvil Press Poetry, took on my first book of poetry, The Structure of Bifocal Distance, and allowed me to design my own book cover with one of my collages.

BW: Do you remember the first collage that made an impression on you?

JD: Once I was drifting around the Tate Gallery, where I saw one of the first collages I can remember. It was called “The Mystic Rose” and was, I think, by one of the Nash brothers—Paul or John. The collage was constructed with a cut-out full-blown rose, hovering in the middle of some vague countryside scene with the sky, if I remember correctly, showing a few drifting clouds.

I stood in front of this collage completely transfixed. Knowing absolutely nothing about Surrealism, this collage spoke to me like nothing I had never seen before! I could work the collage out in my mind, but this simple juxtaposition of the rose against a pastoral background seeped into my psyche. It was disturbing in a way. It astounded me like something that has always been there, but has only recently been discovered.

BW: Was there anything in this particular collage that affected your process of creation?

JD: Perhaps it was from “The Mystic Rose” that I first was able to formulate my main goals in collage: arresting the viewer’s attention by creating an unusual juxtaposition that looked as if it had always existed and appears to be absolutely “natural.”

BW: Did any other Surrealist artists interest you at that point?

JD: René Magritte, Kurt Schwitters, and Max Ernst, especially his three collage novels that I bought in Paris: La Femme 100 Têtes, Une Semaine de Bonté, and Das Karmelienmädchen Ein

Traum.

BW: What was your collage-making process like in the beginning?

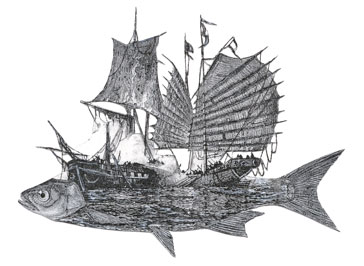

JD: To me, curiosity is the key word for collage. It was always a pleasant pastime for me to cut up images and rearrange them differently, or hopefully to give some pleasing effect, for example, rearranged with a dream-like ambiance. I have often thought that collage is a springboard to express new themes and subjects. It’s all well and good sticking chicken heads on humans and giving flying fish feet for jest, but that’s all been done before.

I say this because the tradition of Ernst appears to carry on infinitely like a machine set in motion. More than three-quarters of a century after his influential hybrid collage figures made a stir, the tradition of black and white collage appears to be still immersed in his imagery and tradition. Oddly enough, I have most recently returned to the hybrids myself to make collage books with a young Russian artist, Dasha Bazanova, about flood myths and global warming, so I guess what Ernst hit upon in his narratives are universal archetypes that will continue to have significance.

BW: What was it like making your collages in those early days?

JD: In the beginning, I was at the time not interested in black and white collage. I started in color. There were so many color magazines, booklets, periodicals, publications with illustrations that the sources seemed endless. I honed my skills at hunting through second-hand bookshops and soon built a collection of colored materials. Also, I found that on certain Friday evenings in London, especially in the West End, offices and shops literally threw out hundreds of printed materials.

I guess, in a sense, I was doing a “Kurt Schwitters”—not constructing like his collages, but leaning toward a figurative style while composing collages out of found scrap materials. I began to construct hundreds of collages with a rubber cement called “Cow Gum” and scissors! Within a month of my collage beginnings, I could have filled a gallery with these creations. I was happy cutting, rearranging images so that they appeared absurd and surreal. Soon a friend introduced me to surgical scalpel blades, which added a further refinement to my technique.

BW: How did you go about studying collage?

JD: I actively took an interest in collage on display. I haunted bookshops, galleries, and museums for collage and books about collage. It certainly was an art that was practiced around the world. It was a popular medium. In Paris in those days (the ’60s), almost every gallery had an exhibition of collages, and by Hover Craft and a pleasant train trip, Paris was within easy reach at a reasonable price. Collage was healthy! So why not partake and join in the movement, “all power to collage,” “change the world by collage.” It was more than a game; it was a philosophy. I believed in collage!

BW: How did you make the transition from color collages to black and white?

JD: At that time I was still actively writing Dadaist and Surrealist poetry and reading a great deal of other things. I came across a line of poetry—it might have been Pablo Neruda or another poet: “I work alone surrounded by men who toil with their hands.” The line stopped me in my tracks. Here I was, sitting at home after working in an office, cutting up colored papers and rearranging them! I felt like an idiot! I looked at all my color collages, bundled them up with all the materials that I had collected, and left them out to be collected the following morning by the garbage men. Good-bye collage, I thought.

I abandoned collage or collage abandoned me, who cares? There was enough of it already drifting around the world—tons of it piling up. It seemed to me that there was a distinction to be made between collage and paste-ups. Many people think their collages are collages when they are actually paste-ups—a collection of hopeless, arbitrary images pasted together in the name of collage.

BW: So what redirected you back to collage?

JD: I discovered George and his barrows at Farringdon Road. George was an open-air book dealer. From him I purchased a box of black and white plates depicting insects. It was much later where I purchased my first set of “hurt” volumes of Picturesque Europe and other sets including Picturesque America, Picturesque Palestine, Picturesque Egypt played a major influence in my concern for the pastoral.

Gradually over the months, I also picked up several bird books, a few by the Rev. J. G. Wood, and a set of The Royal Natural History, edited by Richard Lydekker. I also began to take an interest in his black and white plates of various other themes and topics. Without any purpose in mind, I soon began to build a collection of black and white images in wood and steel engravings. I had no thought of using them as like all the natural history books together with the bird books.

I began to make collages from that black and white material. Black and white collages, I thought, should make me think. They should demolish all the distractions of color and make me want to develop an idea of structure within its limitation. Fighting against the grain of color collages should push me to struggle to say some things that are extremely difficult to express in a limited form.

BW: So what was the subject matter of your first black and white collages?

JD: My earliest black and white collages were figurative scene in the Surrealist tradition, arresting and disturbing. They were dramatic and often accepted for magazine illustrations.

The major change in my work came in the 1980s. I was already living in America, and that was when I realized that my book materials—made from wood pulp paper—were acidic and that “Cow Gum” dries out. I made a trip to visit the paper conservation lab at the National Library in Washington, D. C., where I first became aware of archival papers and pastes. This led to writing The Collage Handbook in 1985 and completely rethinking my ideas about collage materials.

The major change in my work came in the 1980s. I was already living in America, and that was when I realized that my book materials—made from wood pulp paper—were acidic and that “Cow Gum” dries out. I made a trip to visit the paper conservation lab at the National Library in Washington, D. C., where I first became aware of archival papers and pastes. This led to writing The Collage Handbook in 1985 and completely rethinking my ideas about collage materials.

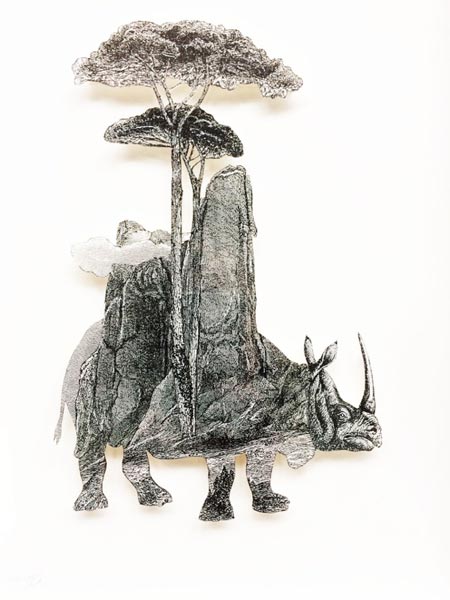

Nineteenth-century black and white engravings of people and places were plentiful enough, but how to use them in a new way involved archival considerations and the idea of recycling. I learned how to de-acidity paper. My images of birds, butterflies, animals, and fish took on new meaning when I started to think about the destruction of nature and of the human cultures depicted in my old books.

I decided then to do a series of butterflies depicting people from around the world dancing traditional dances. I also wrote a book of my own poetry with butterfly illustrations. It was called Fluttering with an Attempt to Fly (1994). The fragility of butterflies that manage to migrate over wide territories had always interested me as paradoxical. In leafing through books about voyages around the world, the idea of butterflies making their journey had come to mind again, so I began to imagine them as witnesses to sacred dance around the world.

BW: Can you describe the techniques that you use in making your collages?

HD: The essence for all is the same. Cutting delicate pieces of paper and integrating them so that the completed image appears seamless. In all my work, I back image papers onto long-fibered mulberry paper so that I can easily cut with a scalpel blade without tearing the images.

My early work included hundreds of birds and animals made this way, and I continued doing them for decades probably because of my love to them. In one early series, I came upon a new style. I was into doing figurative work, and I was cutting out a figure from an illustration that happened to be an old French journal that was falling to pieces. I had purchased the volume from one of the bookstands along the Seine. I kept the figure, which I was going to use for a collage, to one side. I placed the background to another side and started working with the figure I had cut out and other pieces I had cut out for the collage. As I searched among all the papers and books spread out before me, I suddenly noticed the previous sheet from which I had cut out the figure and saw that in the hollow space where the figure had been another image appeared. It was a landscape on the sheet underneath that it was obviously unrelated to the collage I was working on. I discovered that by combining the landscape with the silhouette of the figure I could create a new kind of collage. The series that emerged was called “Beside Themselves.” I found that viewers interpreted these collages as containing two related narratives, which really pleased me. In general, it appeared as if the landscape and figures in the hollow space were in the thoughts of the characters in the foreground.

BW: Did Max Ernst’s collages have an influence on your black and white collages?

JD: Certainly he or his inventiveness opened up doors in my own unconscious, and his idea of narrative collage continued to influence my figurative style. Whatever might be said, Max Ernst invented or discovered black and white collage. He made it his own. A totally new form of visual

art came into being. That cannot be disputed.

BW: Were there any other collage artists who influenced you at this time?

JD: Around the early or middle sixties, a friend of mine introduced me to the poetry of the Czech writer, Jiři Kolař——I did not know at that time he was a collagist. Later, I was reintroduced to his works as a collagist. I saw a few reproductions of his birds, in which he took out their bodies and replaced them with older colored pictures of renaissance paintings. These struck me as incredibly dream-like.

Also, I was astounded by his collages that were called “rollages” or “cubomania.” These collages consist of using more than two images. He takes the two images and cuts them. into ¼ inch strips and pastes them down alternately, thus creating a movement with two separate images. I must admit that this “rollage” style somewhat fascinated me. The technique was quite simple and yet extremely effective. I began my own “a la “a la Jiři Kolař”” collages and endeavored to progress in this style. So I began making what I call splits in black and white using multiple copies of the same print.

BW: What other types of things influenced your collages?

JD: Both art or myth influenced me, especially the [Australian First Nations peoples’] works—more myth than art. I share the same belief with [them] that all objects—natural ones in the world—have an inner “spirit,” “life,” and/ or “presence.” I made two trips to Australia and then based several series on what I experienced there: “Spirit of the Pinnacles,” “Boomerangs,” The Nymphs,” and The Waves.”

Another perpetual influence has been the poet and artist William Blake who declared as what I take to be his artist’s statement: “Everything that lives is holy.” Among religious art—though I am not in any traditional way religious—I am also fascinated by medieval manuscripts, particularly the structure of dense pages and the amusing “drolleries” that comment around the edges and represent the sexual and secular elements of the manuscripts. I have been making collage “drolleries” for many years, using them to illustrate books and finally making my own book of them.

BW: At some point, you began to create less representational collage and moved more towards

abstraction. How did that happen?

JD: One day, I had an idea for creating abstract collages using illustrated papers in a new way. I pulled out Picturesque America. I had often used the rocks in this book, and indeed I have used the flowing water as well a great deal as fragments of interior landscape in my birds, fish, and animal collages. The rocks themselves have always fascinated me, and in various collages I had manipulated them in all various positions. I decided to abstract the rocks. Firstly I photocopied the rocks sixteen times, and then I cut them out and pasted them on a large, single piece of mulberry paper. I drew over the rocks with paste, and, after the sheet was dry, I abraded the surface with sandpaper. I also did the same with the rolling waves, but this time I used a quick drawing overlay with black ink before abrading the surface the sandpaper.

The results satisfied me. The organic shape of the rocks and water abstracted in this manner gave me a new set of abstract patterns with which I can expand my repertoire of images and textures. I started to do the same with multiple copies of plates from Dover Press books and was able in that way to construct papers of all varying shades from pale gray to black, which I used in a series called “Split Images” and for many other abstract works.

BW: What tools do you use in constructing your collages?

JD: A collagist’s tools are paper, paste and a pair of scissors or blades. Rarely does a collagist draw, sketch—or paint. Firstly a de-acidifying agent is necessary. That is extremely important.

While early collagists used wheat or rice starch, in recent years synthetic co-polymer pastes have become available, and it these are used it is important because they are flexible. A good source for such pastes is a bookbinder’s supply store or a company specializing in archival library materials. Glue should not be used under any circumstances. It is an animal by-product and discolors and eats through paper. Nor should rubber cements or sprays be used. They dry out and the whole work disintegrates as a result. Acid-free papers are important. A wide range is available, and papers that are not acid-free in origin can be de-acidified and given permanence.

With a top-line copy machine or a computer and scanner paper images can also be copied onto acid-free papers. Acrylic medium and gel are also useful to coat papers and give them a barrier against oxidation.

BW: Is there a difference between collage and painting?

JD: The structure of a collage has little to do with the structure of a painting. For example, painting talks about foreground, middle ground, and background, but this sense of space is rarely created by design in collage. Painters seek to give the illusion of volume and depth of field, but collage is more concerned with flatness or surfaces raised outward in layers toward the viewer.

Painting rarely is concerned with edges defining objects; collage very frequently is about the texture of edges. Narrative paintings rarely reference figures to previous paintings, but narratives in collages use figures that already have a reference is prints from which they were taken.

BW: What makes a good collage? Only originality?

JD: There must be something more than that. For me is about ideas and the structure of balance. With all the different images one has at hand, it becomes important to be able to juggle all diverse elements and have the capability to order, to construct a unity that makes a collage.

Collage teaches that nothing is static—everything is on the move, racing toward progress, until progress itself becomes ancient. Collage is a voyage. You never know where it is going to take you.

Poems by John Digby

She Tells Me

She tells me that her flesh is

Inhabited by thousands of birds

I remove the rivers from her

The soft sleeve of sleep

And discover

Twin mountains of blood

In which dolphins suddenly

Flash into the sunlight

She is a child born too soon too late

Time that has lost its passage

A secret gathered from the language of birds

Her hair ripe with the games of sunlight

Now I can imagine her

She turns to song to blood to stone

Circling this world

A flame passing through the earth’s shadow

Merlin Talking to Himself

for Jeremy Reed

Once I could talk to water

And turn it into stone

I could behead the night

With a smile

And turn flowing blood

Into a blazing field of poppies

In any of my former lives

I could walk among the stars

And name every one

And remember each name

I could hold the sun in my left hand

And cool it with my breath

In my right hand

I could hold all the dead

And make them dance

Until they dropped from exhaustion

I could make the birds perch

On the fingers of rain

And make them sing so sweetly

That the stars would rain tears

Even in sleep

I could cut off the legs of a goat

With a wink

And make it fly around the moon

Nowadays

I can only change my shadow into a horse

And make it ride over the tops of forests

And other simple things like that

Bah and they call that a miracle!

As She Was Combing Her Hair

She was strolling past

combing her hair

and the lightning suddenly stretched its muscles

and clapped its hands

then the furniture in my room

began to shudder and sneeze

and everything burst into life

the roof blew off

and dolphins appeared sporting among the clouds

leaping through the smoke rings the sun was blowing

the roses on the wallpaper began singing

they opened their mouths

like tiny fledglings

and musical notes shaped like bubbles

streamed out the open window

everything in the room began to dance

my books my table my small lamp

and my pen too

writing its own wild automatic poem

everything was dancing with joy

I peered out of the window

and saw the sun following her

softly humming to itself

I rushed downstairs

and out into the street

to stop her and drag her back

into the crazy room

but she had simply disappeared

Daughter of Lightning

She steps out of her head

with a necklace of kisses

wound around her throat

and her hair as brilliant

as a village burning

where she walks singing

among the flames

spreading terror

she takes one step forward

and causes whole cities

to take wing

whirling like a flock

of startled birds

she takes a step backwards

and the forests sleeping

between her breasts

shudder with sudden snowfalls

she opens her breasts

and shows you her heart

a ball of dancing flames

she opens her eyes

and shows you

two fathomless seas

in which she stands

directing a parade

of dead through your sleep

she opens her hands

and shows you

cities decaying among

the ribs of distant stars

she opens your eyes

with a kiss of electricity

mingled with pain

and the scent of roses

and beheads you in your sleep

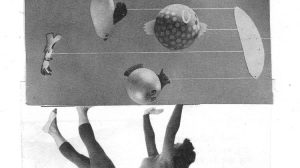

John Digby Discussing the Making of His Collages

John Digby demonstates his techniques as he creates moon collages

Collagist John Digby, introduces his work and techniques

By John Digby

The Structure of Bifocal Distance, Anvil Press Poetry, 1974

Sailing Away from Night, Anvil Press Poetry and Kayak Books, 1978

To Amuse a Shrinking Sun, Anvil Press Poetry, 1985

Miss Liberty, Thames & Hudson, 1986

Incantations, The Stone House Press, 1987

Fluttering with an Attempt to Fly, Ragged Edge Press, 1994

The Arches. with Tony Curtis. Seren Press: Bridgend, Wales, 1998

Me and Mr. Jiggs, lulu.com, 2018

Drolleries, lulu.com, 2019

By John Digby and Hong Ai Bai

Horse Poems in Chinese Tang Dynasty, The Feral Press, 2011

Six Songs from Ancient China, The Feral Press, 2011

Three Neglected Chinese Women: Three Neglected Tang Poets, The Feral Press, 2011

A Break in Passing Clouds: Improvisations on Chinese Poems, Cross-Cultural

Communications, 2014

Passing Memories: A Collection of Chinese Poems on Cold Food Festival, Cross-Cultural

Communications, 2016

Chinese Poet-Emperors, Cross-Cultural Communications / New Feral Press, 2017

Chinese Flower Poems, Cross Cultural Communications / New Feral Press, 2018

Fragile Kingdom: Chinese Insect Poems, Cross-Cultural Communications / New Feral Press;

2018

By John Digby and Joan Digby

The Collage Handbook, Thames & Hudson, 1985

Food for Thought: An Anthology of Writings Inspired by Food, William Morrow & Co, 1987

Inspired by Drink: An Anthology, William Morrow & Co, 1988

Norbert Krapf says

This is a very stimulating and informative interview. I’m impressed by John’s learning from other collegiate but also inventing new approaches and techniques of his own. And the poems following the interview are superb!

Gregory K. Stephenson says

Wonderful interview! I have been a keen admirer of John Digby’s poems and collages since the 1970s. What pleasure they have given me. He´s a wonder of the natural world. Bless him!