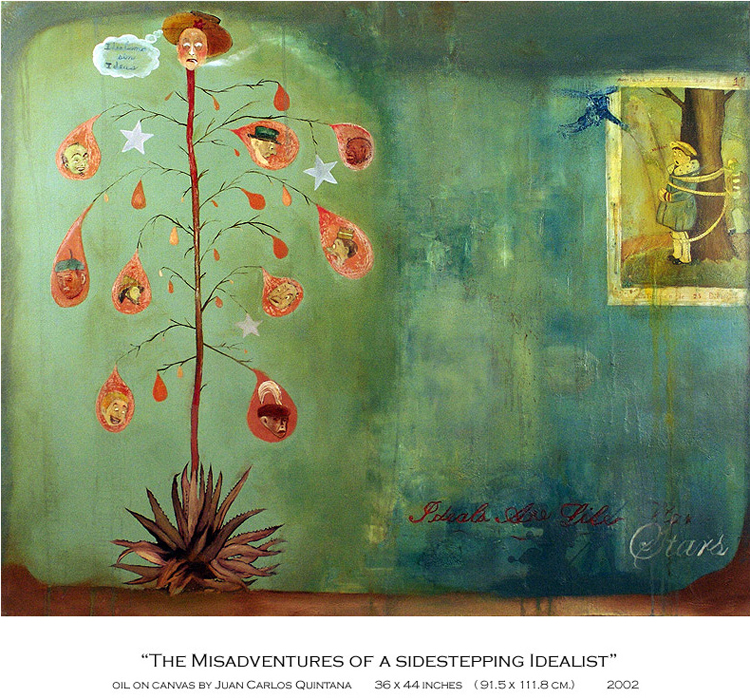

The Misadventures of a Sidestepping Idealist

Mr. Juan Carlos Quintana

Berkeley, California

May 10, 2004

Dear Juan Carlos,

Have you been to the Art Institute of Chicago and seen Picasso's fabulous painting, The Old Guitarist, that he created exactly one hundred years ago?

I'm asking because only when you see the painting itself, as opposed to a reproduction, do you begin to enjoy the fact that Picasso, being short of funds, painted it on top of two layers of his earlier paintings and then later brought out suggestions of the earlier pentimenti images with small, subtle surface touches similar to the way you did in the canvas called Misadventures of a Sidestepping Idealist that I so admired at The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Annex last week. The next time that you find yourself in Chicago, if you look closely enough at The Old Guitarist, (you may have to get down on the floor and look up and then fight off the people rushing up to you that think you've passed out), you can see the other paintings that lie beneath the surface. Picasso also delicately brought forward to the surface the portrait of a female version of his own young face from underneath, you can see it hovering just behind the old man's head; in fact you can even see that face in a good reproduction. If you like poetry, Wallace Stevens wrote a fifteen-page poem about that painting entitled The Man With The Blue Guitar. A line early on in the poem goes:

And they said to him, "But play you must,

A tune beyond us, yet ourselves,...,"

Yes, to answer your question, I'll try to describe "Misadventures" as best I can. It's the blue-green painting with nine small, rather crudely painted, cartoon-like heads, each head ensconced within a petal shape stemming from stems from the trunk of a large yucca-like agave plant, with the inscription that appears to read, Petals Are Like Stars, painted in a beautiful, rich, red script in the lower right. Also hanging from three other branches stemming from the same stalk, are three white stars, two bright and one fading, that aren't really white at all. One is an extremely pale blue, the second is more of a pinkish violet and the third, fading, smaller star is a dull, very pale tan. Those stars make me think of The Three Sisters of ancient mythology, the first spinning the yarn of your life, the second measuring it, and the third cutting it. Or perhaps they symbolize a really weird three-headed watchdog; more about that later. The word Stars is partially painted out and then re-written even more elegantly and rather larger in thick white paint below the original word. I swear that I've seen this painting before somewhere. I can remember looking closely at a scene within a scene in the painting's upper right-hand corner depicting a background of five elongated hillocks behind a little boy wearing a star on his cap, with popping eyes and oval mouth agape, [loosely tied to a tree by the clever hand of the artist (You must have filched him from a page in one of your grandmother's old children's books.), and who seems to be calling out, "AYUDAME," (a neatly printed but as yet indecipherable Spanish word or phrase; which my dictionary now translates as, "Help me!")] to verify that he was truly painted rather than merely collaged onto the canvas. Considering the smooth, almost glass-like, satiny surface of the painting, I suspect that a translucent wax must have been employed over the initial, textured images that appear and disappear and reappear throughout the entire painting.

One of the tubular hillocks has been endowed with little windows in such a way that the windows can be seen as eyes and open mouth, giving the hillock a playfully haunting "Betty Boop" anthropomorphic connotation in spite of its tiny entrance-way far beneath, and in the bottom left corner, a sweet little flower innocently offers itself to any passing bee who might want to take advantage of its full-faced openness. To suggest the many edges of the pages that must lie behind the page that depicts this scene within a scene at the painting's upper edge, and to both heighten and separate it from the rest of the painting, is a three-sided cream-colored boundary infused with minuscule symbols and shapes made to look like exquisite, painterly accidents and spatters speckled over sublimely subtle and delicate, casual yet breathtakingly gorgeous tones of pale peach, pale blues, light pinks, pale-oranges and glowing runs of translucent, rich yellows, all only discernable within the cream upon extremely close inspection. Those splatters evoke a microcosm of both celestial and everyday images: a raised knot in a plank of wood, lichen or mold growing on a rock, animal paw-prints, orbs, teardrops, a quarter moon hanging in a pale-blue square, planets and star clusters glistening within the luminous after-glow of a stunning sunset.

The creamy horizontal top and bottom bars that outline the boy's plight each contain faded Spanish inscriptions, the top referring to the title of the painting boldly followed by the number seventeen, obviously the page number of the book but also implying a more significant second meaning. The inscription on the bottom bar seems to merely refer to a collection of 25 drawings yet at the same time indicates a passage or journey of eight further eventful years from the 17 year-old position inscribed at the top. In a few places within the entire painting, little areas of thickly textured paint appear to have curdled and have then been painted over with the depicter's mock-pretense of the imagery of the final, surface paint ignoring the uneven, disparate, mock-curdled textures beneath the surface, perhaps to playfully tease a fastidious, persnickety eye, but also to lend an additional, slightly jarring physical and cerebral dimension to this marvelous work; the apparent curdling, on a tactile level, having its own separate, unique texture and also, on a conceptual plane, being an indication of the passing of time. The creation of the painting itself, considering its enormous complexity, has very definitely and engagingly evolved over a considerable period of time.

About the nine faces ensconced within the petals: Moving in a widdershins direction, my favorite word for counterclockwise, and looking down through the eyes of the presiding skeptic's unensconced, star-capped head at the top of the agave, the first face looks to be a combination of Mephistopheles and Lenin in a bleary drunken stupor, the petal that contains it mainly scraped back to reveal the paler, pinkish-brown color underneath, leaving the remaining, darker, red-brown in the shape of a flame flickering above his face to further bring out his deviltry. The second, a darkish face hovering within an unscraped petal, wears a green beret with a small curved phallic spindle projecting from the top, quickly connoting artistic affectation or military violence with high libido. The third, a bearded, hooded face, appears to be an explorer or a missionary or perhaps both, simultaneously preaching and questing. The fourth face looks like the roped-up boy a few years later, still hysterical and dazzled by the uncertainties of existence. Moving across to the other side of the bottom of the petals on the stalk, we see a pensive simian face residing under an elegantly plumed 16th Century hat that still resembles the affectation of a fancy version of an artist's French beret. Above him is the arch-eyebrowed, tilted face of a scolding inquirer, probably the artist's father although his gender is not quite certain. Blabbing away over him is the profile of an old biddy, we won't say whom, wearing a ridiculous pill-box hat and yakking away about something completely irrelevant and totally meaningless. The face of a nice old white-bearded, green hatted man wondering if the biddy will ever shut up, floats over her, and almost parallel to him is his gleefully vicious animal, sharp-toothed Mister Hyde other self uniquely stemming from the same branch. Perhaps the presiding skeptic residing above it all on the agave's top perceives them all to be idealists without significant ideas. The inscription below, after closer scrutiny, actually reads, Ideals Are Like Stars. Behind the agave growing on the edge of the red desert that borders what must be a river or swamp, is a background of opaque, pale, glowing green that almost obscures the faintly seen rungs of Jacob's ladder rising to the heavens, yet notwithstanding, creates a marvelous opaque mist of a quality quite separate from that of all the intricate, fluctuating images on the right side of the painting that hover within the translucency of the river. It is a multi-toned mist that cleverly provides the viewer with a delicately receptive screen upon which unsuspecting observers, if in a calm enough state, may project their own fleeting, vaporous, pale-green, glowing retinal afterimages emanating out from the outside edges of the petals. A discerning eye will acknowledge the artist's compassionate artifice in his act of creating very pale green false afterimages outside the edges of many of the petals in order to kick-start the glowing halos around the petals that are ultimately both perceived and produced by the viewer's own interior retinal mechanism and thereby allow the artist and the viewer to be mutual participants in the effects of this utterly remarkable painting.

I instantly, without a moment's hesitation, bought the painting last week on the first glance and only much later "remembered" (déjà vu?) that I had seen it somewhere before and that I had also been intrigued by the five-inch, slightly eroded dark-blue smudge looking as if it were stamped onto the painting, that turned out to be a floating, wicked looking, modern-day mechanically-propellered-angel whose magical hand has just created a gorgeous stroke of stolen, pale-pinkish-peach above a glowing gray-violet mist through which he is tossing some unrecognizable object or essence to the boy who himself, seems unaware of the little, alligator-fish man with the ready-knife-in-hand lurking just behind him in the background. That creature alludes to art history by wearing Matisse's tilted Moroccan cap and a red and white striped tee-shirt underneath his jacket not dissimilar to the shirt worn by Monet in Manet's famous portrait of Monet on a warm summer's boating outing. Is that creature there to punish the boy or to cut him loose? Or perhaps he's not wielding a knife at all, yes I see now that it could be a thin piece of rope, made smaller than the thicker rope in the front of the tree because it lies in the receding distance, and that the alligator-fish man is the one who's binding the boy to the tree! The adventure within the marvelous, awe-inspiring blending of the narrative into the aesthetic goes on and on and with never a dull moment or a meaningless, wasted stroke. Is the gray, silhouetted person plunging his pole into the liquid at the bottom of the painting, Charon, son of Erebus, at the edge of the river Styx? Or is it the boy, spearing or netting a fish at an earlier time and now soon to be punished by the demons of the water-world? And what is that strange-looking plant with the strange-looking, circular, little ball-shapes on the end of tongue-like protuberances to the left of the boy's silhouette and to the right of the huge, hovering, cat-like face that's six times its size? Is that strange plant, deftly silhouetted over a massive shape that alters between being a giant tortoise and a beached whale, only pretending to be a plant and is actually Cerberus, Charon's three-headed watchdog with a dragon for a tail? Those circular shapes could be the coins needed for travelers to put under their tongues in order to cross the Styx and enter the kingdom of Hades, the place where all souls must go, whether good or bad. Hercules, fulfilling the last of his twelve labors, wrestled that ornery watchdog to the ground and hauled him off to earth for a while even though Cerberus' ferocious dragon tail had bitten poor Hercules on his ass. Eventually, Cerberus got back to Hades again only to find himself pacified into inactivity as a result of his slurping up a bunch of honey-cakes supplied by Aeneas and Psyche. Hades' other name was Pluto, which is why we named that planet's satellite "Charon." Pluto is the sun's only planet not yet visited by a spacecraft but I hear that one is on the way. It's a curious fact that both Pluto and Charon rotate in exactly the same amount of time, each taking 6.387 times as long as the length of a single day on earth.

But let's get back to the actual painting.

The images that this painting conjures up seem to be unending. I've never seen a painting that triggered so many stories and subtleties. The vestige of a young woman blithely running forward from the top of the center of the painting distracts the eye from the large, moody, beaked head of a mysterious bird staring into the distance just below her. Like the disproportionate configurations sometimes combined in ancient Indian miniatures, two tiny squiggles of paint set within the desert's edge become distant mountain ranges that throw the viewer's otherwise close-up viewpoint miles away from the point of entry.

Those silhouetted gray shapes aren't really gray at all; they're a strange chameleon-like mixture of colors, gray-violet at one moment, gray blue-green at another. Ah! Perhaps those vegetative ball-shapes are pads on the tips of the tongues of the chameleons, put there to, among other things, call your attention to the fluctuating color that once merely seemed like a colorless gray. When the whale's image predominates, the turtle's head transforms itself into a dangerous, lichen-covered rock protruding above the surface of the Styx. The rock soon becomes a benign, floating, aquatic bird quacking away at the boy holding the pole; and directly over him, twice the size of the entire boy, looms a large, ghostly, frontal version of the face of the green-hatted man with the white beard, looking unnervingly like Henri Matisse in his later years. A second image of the large, hatted face then superimposes itself and slides downwards in a multiple-exposure manner similar to Marcel Duchamp's nude descending a staircase or an early photo by Eadweard Muybridge taken on the Stanford farm. With closer inspection, the curdles, whatever they are, have the appearance of fragments of tiny, painted-over, spider-like, delicate vegetation; one set of that pentimenti delineates a stylized, seated lion sitting upright with his bird-like consort, proudly perched atop a giant, mystical fish worthy of a Remedios Varo bestiary. A tiny brown outline depicts a smiling Asian woman wearing a floral hat much more elaborate than that worn by Matisse's green-faced lady that coincidentally also hangs in The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Seated in her intricately painted barque with her two attendants respectfully standing upright to better observe and protect her from the many dangers of the river, she is pleased to note that her journey is half-way over as she prepares to pause to pluck petals from the delicate shrubbery floating behind her head in a calmer area of the river.

But it's not just the remarkable imagery that speaks to me; the entire structure of this amazing work, all twenty-eight of the most important aesthetic aspects that make up a painting (and the subcategories beneath them) are absolutely superb! And done so casually, with such ease, assurance and honesty and with a remarkably rare and wonderful, layered undercurrent of subtle, ironic and sometimes wicked humor! What superb and honest craft! For example, paint runs; so let it run a little. Let it do what is natural to it; and besides that, the little boy seems terribly frightened. Bertolt Brecht did the same kind of thing in his plays to call the audience's attention to the fact that these are not real people but only actors on a stage expressing something, in order to remind the viewer that noticing the artifice of the craft allows for perceiving connotations deeper and more significant than the moment's first impression. I like this painting so much that I want to know more about its history, [where each of the enneadic heads on the petals of the yucca plant comes from, and who that woman is on the very top, what the devil is that thought cartoon-ballooning from her head? "Idealism without Ideas"? It sounds cynical; or at least skeptical; is she actually the anima-figure of the artist? What kind of cigarette is he smoking? Why is that star on his hat? What do the Spanish words truly mean?, not just literally but all their connotations? What or who is each singular source of those nine heads, nine like the nine planets, and who are the four, large, pentimento portraits with the deep-set, heavy-lidded eyes, obscurely hovering in and out of one's perception along with a lot of other haunting hide-and-seek Rorschach-like images and inscriptions in the Stygian-marsh center of the painting that you don't see at first because in the very center of it all, with six casual, small, blunt strokes of washed-over white, you're looking at a perfect rendition of the boy in the distance, sitting on a rock, his hat unmistakably the same; was this the boy before now, before his bound, roped-up moment, or after?; and on and on], and to eventually meet its maker, Juan Carlos Quintana.

© 2004___ Muldoon Elder