“Time stops. He’s filling empty space with the substance of our lives, confessions of his bellybottom strain, remembrance of ideas, rehashes of old blowing. He has to blow across bridges and come back and do it with such infinite feeling soul-exploratory for the tune of the moment that everybody knows it’s not the tune that counts, but ‘IT–‘ Dean could go no further; he was sweating telling about it.”

–Jack Kerouac (1957), quoted from On the Road

In ancient Native American cultures there was a person designated to tell the stories of his people: what they have been through, what they believe in, and how they have changed. Many of those people have since died off, and with them their stories–their identity. So, who are our storytellers? Who are the ones looking through shamanistic eyes and telling us something about ourselves and our world? They are our authors, our poets, and our muses; they are the ones who have the ability to tell us about who we are and how we live. Some believe this person is dead: a martyr for the sake of literature and the reader. As Roland Barthes proclaims, “…we know that to give writing its future, it is necessary to overthrow the myth: the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author” (Image 148). In pre-postmodern American culture, however, Jack Kerouac emerged as the Author-reincarnate, so to speak. His most popular novel, On the Road, presents readers with a highly autobiographical text that does more than simply tell of Kerouac’s own adventures on the road: it speaks to a generation about non-conformity, identity, transcendentalism, and the search for “IT”–complete self-realization.

The concept of the “Death of the Author” is not new, nor is the criticism of Kerouac’s autobiographical style. Under the Barthesian ideology, Kerouac’s style of writing is not only damaging to the reader but also to the future of literature itself. The pleasure derived from reading and finding meaning in a text, Barthes argues, should come solely from the text itself; an Author does nothing more than write the words. “To give a text an Author,” he says, “is to impose a limit on the text, to furnish it with a final signified, to close the writing” (Image 147). The text looses a certain element of meaning the moment we begin interpreting it based on who wrote it, when it was written, and under what conditions it was written. Essentially, the reader is lost in what he/she thinks the Author wants them to take away from the text. There is no longer room for interpretation; readers need only look to the writer rather than the written. Ironically, Kerouac’s On the Road is a first person narrative, in which the main characters are based loosely on actual people and events. Automatically, readers are thrust into the mind of the Author, for without his own experiences the novel may have never taken shape. However, Kerouac, much like Michel Foucault, urges us to ask ourselves: “What difference does it make who is speaking?” (Foucault 275). Sometimes, it is not who is speaking but what he is saying that really matters. Personal experience as a basis for narrative writing not only blends reality and fiction, but also reinforces meaning by creating worlds, ideas, and people that the reader can relate to.

Kerouac and other writers of his generation fully and tragically understood the impact reality could have when paired with fiction. According to Mark Richardson:

The Beats rejected the modernist aesthetic as productive of art that had become, over the years, esoteric, obscurantist, elitist, safe, sterile, dead. Beat poetics called for rebellion against all forms of authority, especially culturally sanctioned authority,…It rejected the notion that the artist must distance himself from his material, seeing in it an unhealthy need to control or contain nature, life, people; the Beats preferred to ‘dig it.’ (Richardson)

On the Road, the novel some call the bible of the Beats, epitomizes this ideal that Kerouac so steadfastly believed in. It is not Kerouac’s, or for that matter Sal Paradise’s, life that carries the weight of the meaning, moreover it is his experiences and the meanings they carry. “And this was really the way that my whole road experience began,” says Sal, “and the things that were to come are too fantastic not to tell” (Kerouac 7). Kerouac, the Author, does not ask his readers to look through his own eyes and see things as he saw them; rather, he paints a vivid picture of what life was actually like for the normal, working-class citizen. He does not urge readers to go on the epic journey of Sal Paradise: that is too much to ask. Nor does he ask his readers to seek out the underbelly of America: the hobos, the drug addicts, the Mexican migrant workers, or the Negro jazz musicians as Sal Paradise inadvertently has. It is experience, passion, and madness that he asks his readers to confront. Kerouac’s own passion and madness is only a means to reach the ends; “Experience…,” Martin Jay says, “…may well survive the death of the modern subject and the exhaustion of the dialectical model of redemptive history, mutating in ways that are still to be determined” (475).

Kerouac conveys his experiences in On the Road by creating scenes and characters that closely mirror aspects of his own life. More specifically, Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty represent, without a doubt, the unique relationship between Kerouac and Neal Cassady–the rebel prince of the Beat generation. On the Road, as Tim Hunt says, is in fact “…a case study of Cassady told in Kerouac’s own voice as part of his own autobiography” (109). As would be expected, Kerouac’s fascination with Cassady flows over into the novel itself, and represents a shift in Sal Paradise’s otherwise menial life:

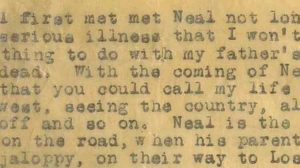

I first met Dean Moriarty not long after my wife and I split up. I had just gotten over a serious illness that I won’t bother to talk about, except that it had something to do with the miserably weary split-up and my feeling that everything as dead. With the coming of Dean Moriarty began the part of my life you could call my life on the road. (1)

The novel is split from the very beginning between the life Sal once had, and the life Sal embarks upon. Ironically, it is not Sal’s previous life that Kerouac asks readers to consider: he devotes only two sentences to it, and even then does not explain Sal’s illness or the split with his wife. Instead, he wants readers to focus on Sal’s “fantastic” experiences and the people he meets along the way. Had Kerouac devoted too much time and energy explaining Sal from the beginning, readers would, conceivably, sympathize with him rather than relate to him. “Kerouac’s style [in these opening statements],” argues Omar Swartz, “warns the reader that something different is going to happen in the text; the opening tone is a flag that prepares the reader for a different type of reading experience” (62). That experience is the unfolding of something new and different in American culture; just as Sal’s old life was “dead” so were the lives of countless American youths’. When he sets off on the road, however, there is promise of a break from the old, a new beginning–a new life.

For Kerouac to make this connection with his readers he surrounds Sal with people from every scope of American life: people he knew would affect Sal just as they affected him. People, especially Dean, are after all the ones who embody the state of mind Sal is searching for. Tragically, he seems to always fall short of connecting with them: “But then they danced down the streets like dingledodies, and I shambled after as I’ve been doing all my life after people who interest me, because the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn…” (Kerouac 6). Like the youth of America, who Kerouac writes to, Sal searches in people for something that will free him from the constraints of normalcy. In Dean he sees a certain spontaneity and freedom, and in the road he sees a means by which to reach that same state of mind. Once on the road, Sal begins to realize that the state of mind he desires is not one that is found, rather it is one that is earned much like Dean’s “…dirty workclothes [that] clung to him so gracefully, as though you couldn’t buy a better fit from a custom tailor but only earn it from the Natural Tailor of Natural Joy, as Dean had in his stresses” (Kerouac 7). Kerouac saw first hand how people could affect one another much like Roland Barthes witnessed how the Author could affect the reader. As a writer, Kerouac was motivated by the notion that his fiction would affect people; however, he first asks readers to make connections with his characters not their real-life counterparts; he wants them to connect with: Sal’s naivety, Dean’s madness, Carlo’s intellect. At the same time, he wants them to realize there is more to experience than what is conveniently placed at their footstep. Just as the text has meaning beyond Kerouac, the world has meaning beyond the readers’ backyard.

Whether or not Kerouac’s methods for constructing On the Road were the result of his own feelings of stagnation, or whether his feelings resulted in his methods is not clear; however, the resulting prose style can be seen in the narrative structure as well as its meanings. “[Kerouac] calls for a highly personal and confessional narrative, one scribbled down without correction and at a high speed in a quest for spontaneity and, consequently, authenticity…” (Malmgren 61). Essentially, Kerouac’s spontaneous prose method called for the utmost honesty from the author no matter how raw or unpleasant it was. Spontaneous prose, by its very nature, relies heavily not only on the experience of writing but also the experience of living. Kerouac believed this was the one true way to convey meaning to the reader. “If you don’t stick to what you first you first thought, and to the words the thought brought,” Kerouac said, “what’s the sense of bothering with it anyway, what’s the sense of foisting your little lies on others?” (qtd. in Malmgren 61). The constraints the literary world placed on the author bordered on lying to the readers; authors were expected to produce texts that were meaningful in themselves. If the author is not part of the text, if he himself does not find meaning in the text, how can anyone else? “In removing the personal touch from author and reader in the momentary cultural commune of reading,” argues Donald Keefer, “Barthes removes the ethical element; he extracts any notion of what an author might owe [his] reader or what the reader might entrust to an author” (Keefer). The only way for spontaneous prose to work, was if the author dove head first into his own psyche to pull out every experience, every emotion, and every heart-felt moment and put it down on paper. The end result of Kerouac’s toils included On the Road.

Ironically, the same principles that govern On the Road, also govern Sal Paradise both in his writing and in his life. Sal is, after all, a struggling writer who in the beginning has no job and is surviving off his GI bill. According to Steve Wilson, “The fundamental irony of the quest recounted in On the Road–an irony Kerouac himself expressed–was that [Sal] was a writer, to most working-class sensibilities a questionable occupation at best, at worst comfortable and lacking hardships” (303). When Sal was living in his aunt’s home in Paterson, New Jersey, writing was his profession; similarly, Kerouac himself “…repeatedly referred to writing as ‘his work,’ and set goals for himself that required physical and psychological sacrifice for his art; drinking to excess, taking speed to fuel three-day writing orgies, developing his technique of trance-like composition, abandoning relationships that might lead to stability” (Wilson 304). Much like Kerouac himself, who relishes the value of experience in writing, Sal abides by the rules of spontaneous prose in the composition of his novel. His ability amazes Dean: “Man, wow, there’s so many things to do, so many things to write! How to even begin to get it all down and without modified restraints and all hung-up on like literary inhibitions and grammatical fears…” (4). He practices spontaneous prose, the same spontaneous prose Kerouac uses to construct the character of Sal Paradise himself. Unlike Kerouac, however, Sal abandons the ideals of spontaneous prose later in the novel while staying with his friend Remi Boncæur in Mill City. “I was to stay in the shack and write a shining original story for a Hollywood studio….I spent countless rainy hours drinking coffee and scribbling. Finally I told Remi it wouldn’t do; I wanted a job; I had to depend on them for cigarettes,” says Sal (64). Under his present circumstances–writing a story he knows will be commercialized and loose meaning–Sal is unable to put any true feeling into his text: “…the trouble with it was that it was too sad” (64). Inevitably, as Koos van der Wilt points out:

Spontaneous prose gives On the Road its iconicity, its similarity between meaning and text with which this meaning is conveyed. Spontaneous prose is the technique that explains much about the minimal aesthetic distance between Kerouac and Paradise–and the former’s recreation of himself as a writer/protagonist. After all, an experimental prose style effectively communicates the search for a new self. (119)

Does this endanger the reader? Does the text somehow loose meaning when the Author bases his stories on himself and his belief in experience and spontaneity? Kerouac’s use of spontaneity to define both Sal Paradise and the text reinforces the changes he sought to elicit in the youth of America; it is spontaneity that sets the text free, and has driven countless Americans to search for something more; it has shown everyone that it is okay to act and react on intuition, without any constraint.

At this point, it is important to return to the notion of “the Death of the Author” as purported by Barthes and Foucault. “The notion of writing, as currently employed,” according to Foucault, “is concerned with neither the act of writing nor the indication–be it symptom or sign–of a meaning which someone might have wanted to express” (265). As we have seen with Kerouac and his composition of On the Road neither of these inclinations hold true when the text is fully scrutinized. As an Author, Kerouac was concerned with both the message of his text as well as the method in which it was crafted. As William S. Burroughs once said, “The only real thing about a writer is what he has written and not his so-called life” (qtd. in Weinreich 148). The road as it appears in Kerouac’s On the Road is not simply made up of asphalt, gravel, and yellow lines. Nor, is the road an end in itself; it is merely the means by which Sal arrives at the end. Dean Moriarty takes him on a fantastic journey across the heartland of America, and is the catalyst by which Sal is able to reach personal enlightenment. According to Malmgren, the more important feature of On the Road is that it:

…seems very easy to read (if a trifle embarrassing in places) just because it invites a ‘reading.’ A ‘reading’ is the kind of activity the readerly test (Barthes’ lisible) elicits from the reader–the formulation of a total, comprehensive vision of the world depicted in the text. On the Road invites (one might even say demands) just such a reading. (64)

On the Road has become a cultural phenomenon, and a part of literary history. Its themes of self-realization and spiritual freedom speak across generational boundaries, and captures what Americans have been feeling since the post World War II era.

The continual misinterpretation of On the Road, albeit a highly documented phenomenon, should not rest completely on the author as Barthes would like us to think. The popularity of On the Road delivered Jack Kerouac to heights of iconicity rarely achieved by other American writers. “[Young people],” according to Ann Charters, “recognized that Kerouac was on their side, the side of youth and freedom, riding with Cassady over American highways chasing after the great American adventure–freedom and open spaces, the chance to be yourself, to be free” (Charters qtd. in Swartz 101). His public image resulted in a largely commercialize image that has superceded his work and the meanings he was attempting to convey in his texts. In this capacity, Barthes’ critique of contemporary fiction holds true to On the Road–when commercialized to the extent Kerouac has been, it is necessary for us to kill the commercialized Author. “[Ihab Hassan] cautions that a writer’s reputation has the capacity to ‘turn cannibal, and devour both Man and Work,’ just as the ‘image of Kerouac’ has cannibalized the man and erased his role as a writer” (Johnson). Since the initial publication of On the Road in 1957, Kerouac and the Beat generation have been diminished to social commodities; however, readers with the knowledge and courage to look past the commercialized Author that is sometimes associated with On the Road will find the true meaning Kerouac intended to convey when he wrote it.

Now, referring back to our original paradox, who are the storytellers of our generation if, as Barthes declares, our Authors need to be sacrificed for the benefit of their art? Under these conditions, who has the ability to keep our stories alive? Donald Keefer argues, “The ‘death of the author has given birth not to the reader, but to a booming industry of ‘discursive practices,’ or the production of texts on text” (Keefer). Through the mists of meaningless texts written to disconnect the Author and his work, Jack Kerouac came through as a breath of fresh air for Americans searching for true and unique meaning in literature and life. On the Road poses readers with a universal questions concerning personal identity. In order to find answers to these questions and convey them effectively to his readers, it was necessary for Kerouac to place himself in the role of the Author and protagonist. Sal Paradise achieves self-enlightenment ‘on the road’: when he first began his journey he did not know where he was going or what he would find–all he knew was that it was the sign of change. Likewise, at a time when the youth of America were searching for meaning wherever they could find it On the Road gave them their answer. Enlightenment, they learned, is achieved through one’s own courage to seek out experiences that will lead him/her down the road to enlightenment. The road, however, is not an ends in itself; rather, it is the means to reach the end. Kerouac realized this by traveling it for seven years and as readers we come closer to finding meaning in his texts by recognizing the limitless possibilities in life and literature.

Works Consulted

Barthes, Roland. Image, Music, Text. Trans. Stephen Hill. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977.

—. The Pleasure of the Text. Trans. Richard Miller. New York: Hill and Wang, 1975.

Dardess, George. “The Logic of Spontaneity: A Reconsideration of Kerouac’s ‘Spontaneous Prose Method’.” Boundary 2. 3 (1975): 729-43.

Foucault, Michel. “What Is an Author?.” Contemporary Literary Criticism: Literary and Cultural Studies. Eds. Robert Con Davis and Ronald Schleifer. New York: Longman, 1989.

Hunt, Tim. Kerouac’s Crooked Road: Development of a Fiction. Berkeley: U of California P, 1981.

Jay, Martin. “Roland Barthes and the Tricks of Experience.” The Yale Journal of Criticism. 14.2 (2001): 469-76. Project Muse. 8 April 2002.

Johnson, Ronna C. “‘You’re Putting Me On’: Jack Kerouac and the Postmodern Emergence.” College Literature. 27.1 (2000 Winter): 20-38. OCLC First Search. 17 March 2002.

Keefer, Donald. “Reports of the Death of the Author.” Philosophy and Literature. 19.1 (1995): 78-84. Project Muse. 20 March 2002.

Kerouac, Jack. On the Road. New York: Penguin, 1957.

Levine, George, ed. Constructions of the Self. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1992.

Lyotard, Jean-François. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1984.

Malmgren, Carl D. “On the Road Reconsidered: Kerouac and the Modernist Tradition.” Ball State University Forum. 30.1 (1989 Winter): 59-67.

Richardson, Mark. “Peasant Dreams: Reading On the Road.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 43.2 (2001): 218-42. Project Muse. 8 April 2002.

Swartz, Omar. The View from the Road: The Rhetorical Vision of Jack Kerouac. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1999.

Van der Wilt, Koos. “The Author’s Reconstruction of Himself as Narrator and Protagonist in Fragmented Prose: A New Look at Some Beat Novels.” Dutch Quarterly Review of Anglo-American Letters. 12.2 (1982): 113-24.

Weinreich, Regina. The Spontaneous Poetics of Jack Kerouac: A Study of the Fiction. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1987.

Wilson, Steve. “‘Buddha Writing’: The Author and the Search for Authenticity in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and the Subterraneans.” The Midwest Quarterly. 40.3 (1999 Spring): 302-15. OCLC First Search. 20 March 2002.