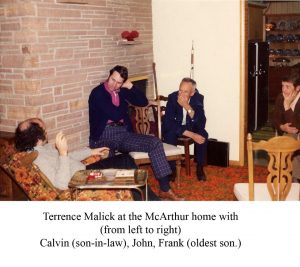

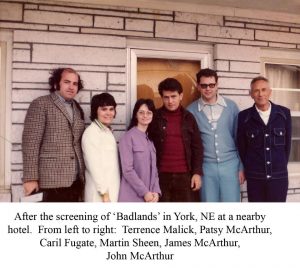

Photos courtesy of Jeff McArthur (All Rights Reserved)

Jeff McArthur is the author of Pro Bono: The 18-Year Defense of Caril Fugate. Mr. McArthur’s grandfather, John C. McArthur, defended Caril Fugate in her trial for her part in the Starkweather murders that occurred in 1959 and would do so for the next eighteen years in her attempts to apply for parole.

Fourteen-year-old Caril Ann Fugate was associated with a spree killer named Charles Starkweather who was convicted of murdering eleven people throughout the Badlands of Wyoming and Nebraska. They were captured on January 29, 1958 and, seventeen months later, Starkweather was executed. Fugate, who killed no people, spent her next seventeen years in prison.

In the book Pro Bono: The 18-Year Defense of Caril Fugate, her chief defender’s grandson, Jeff McArthur, details Fugate’s trial and, in one chapter, details her involvement with the film Badlands, a 1973 Terrence Malick film. Sissy Spacek played Holly, a character loosely-based on Fugate.

In the book Pro Bono: The 18-Year Defense of Caril Fugate, her chief defender’s grandson, Jeff McArthur, details Fugate’s trial and, in one chapter, details her involvement with the film Badlands, a 1973 Terrence Malick film. Sissy Spacek played Holly, a character loosely-based on Fugate.

Criterion has recently re-released a digitally-remastered print of Badlands on Blu-Ray with the complete involvement of Malick.

Recently I had the opportunity to ask Mr. McArthur a few questions about Fugate’s involvement with Malick, her reception of Badlands and her fondness for Martin Sheen’s performance.

Accompanying the interview are some previously-unpublished photos of Caril Fugate, John McArthur, actor Martin Sheen, and Terrence Malick.

Mr. McArthur’s book is available on Amazon.

Terrence Malick first began working on Badlands in 1972. When he was finished, before he began filming, did he ever let Caril read the script?

No. But he did meet with her before making the movie, and he determined that if she didn’t want him to make the movie, he wouldn’t. She trusted him because he seemed like a straight forward kind of person. He then showed it to her when it was finished.

Did she feel different about it later?

Not to my knowledge. For the most part, she couldn’t relate to it as a movie because it was close enough to the real story to be able to look at it objectively, but not accurate enough to capture the emotions of what really happened.

How did she perceive Terry Malick? Was she trusting of him?

How did she perceive Terry Malick? Was she trusting of him?

Very much. The whole reason she gave her blessing to the movie was because of what a stand-up and kind person he was. She wasn’t familiar with his work, as I understand, but she liked him a lot. In fact, even when afterward she said she wasn’t crazy about the movie, she continued to make it clear to them that she really liked Terry and especially Martin, who she stayed in touch with for years.

What did Caril see in Martin Sheen’s performance?

She said he was hauntingly like Charlie. Actually, she basically said it was the only thing about the movie that was really like the true incident. I’ve learned since writing the book that she actually slapped Martin on the back as they were leaving the theater and said, “Charlie, you’ve come back to haunt me.”

I wrote this in One Big Soul: An Oral History of Terrence Malick and it is sourced from an acquaintance of Caril’s named Linda Battisti: “After filming, Malick secretly arranged a meeting with Fugate and her lawyer, Jim McArthur in a hotel to obtain her signature to prevent any potential lawsuits. What ensued isn’t known other than Fugate’s impression was that she hoped the film would improve her chances for parole. After viewing Badlands, Fugate felt that though Martin Sheen’s performance was “dead on,” that of Sissy Spacek’s portrayal of “Holly” made Fugate seem “psychopathic.”

I wrote this in One Big Soul: An Oral History of Terrence Malick and it is sourced from an acquaintance of Caril’s named Linda Battisti: “After filming, Malick secretly arranged a meeting with Fugate and her lawyer, Jim McArthur in a hotel to obtain her signature to prevent any potential lawsuits. What ensued isn’t known other than Fugate’s impression was that she hoped the film would improve her chances for parole. After viewing Badlands, Fugate felt that though Martin Sheen’s performance was “dead on,” that of Sissy Spacek’s portrayal of “Holly” made Fugate seem “psychopathic.”

Oh! Well, Linda’s pretty knowledgeable about a lot of things, and some of that I know is dead on. They did get together and watch the movie, but it was not to help with parole. In fact, they were specifically more worried about the opposite, that it might hurt her parole chances. Terry wanted to put my father and grandfather in the credits, but he left it out because of the fear of what it might do to parole. So, instead, he put an inside joke, one of the last lines of the movie, where Holly says that she married the son of her lawyer. That was an inside joke with Terry and my dad because they had become friends.

Can you share more about your father’s relationship with Terrence Malick?

I’ll do my best. Of course, it’s always hard to describe a friendship. They stayed in touch and spoke on the phone each week while Terry was making the film, and after that about once every few months. They drifted apart, as people often do, but at least once a year one would get in touch with the other to see how things were going. Terry’s a very quiet and introspective man, and my father is very talkative, so I think that accounted for a lot of the dynamic. Also, one thing that’s interesting about Terry is that he is always interested in various things, particularly outside of the film industry, so he seems to have always liked talking with someone who has other interests and areas of knowledge. They still talk every couple of years, usually when one sees something the other might be interested in. Oh yes, and as I understand it, Terry got the idea for Days of Heaven when he went to Pioneer Village with my mom and dad. It’s the same Pioneer Village that is joked about in the South Park episode that’s a parody of Die Hard. Terry probably saw the sign for it when they were going out to visit Caril at the reformatory. (There’s a huge sign for it just before York.) However, they decided, I’m sure he was interested in going because that’s just the way he is, always interested in something that’s a little different. Very outside the usual Hollywood self-interest that you usually see from filmmakers.

I’ll do my best. Of course, it’s always hard to describe a friendship. They stayed in touch and spoke on the phone each week while Terry was making the film, and after that about once every few months. They drifted apart, as people often do, but at least once a year one would get in touch with the other to see how things were going. Terry’s a very quiet and introspective man, and my father is very talkative, so I think that accounted for a lot of the dynamic. Also, one thing that’s interesting about Terry is that he is always interested in various things, particularly outside of the film industry, so he seems to have always liked talking with someone who has other interests and areas of knowledge. They still talk every couple of years, usually when one sees something the other might be interested in. Oh yes, and as I understand it, Terry got the idea for Days of Heaven when he went to Pioneer Village with my mom and dad. It’s the same Pioneer Village that is joked about in the South Park episode that’s a parody of Die Hard. Terry probably saw the sign for it when they were going out to visit Caril at the reformatory. (There’s a huge sign for it just before York.) However, they decided, I’m sure he was interested in going because that’s just the way he is, always interested in something that’s a little different. Very outside the usual Hollywood self-interest that you usually see from filmmakers.

Were there any legal demands placed by your father concerning the Charles Starkweather/Caril Fugate story?

I know that they made out a contract with the distribution company that no theaters could use the true story for advertising. So they couldn’t say, “Based on a true story.” In fact, Terry personally followed up on offenders.

A few years back, Mr. Malick was trying to locate Caril. Do you have any idea why he wanted to reconnect with her?

I can’t even imagine, and I’m pretty surprised that he would. However, I did contact him while writing this book, and I sent the chapter called Badlands after it was done. He apparently really liked it, so maybe that stirred something in him. But I don’t know. I don’t talk to him very often myself. He’s pretty reclusive, even to long-time acquaintances, but next time I have a good reason to talk to him, I’ll ask.

I just thought of a quote I would like to give you, because this sort of sums up my feelings about my involvement with the movie throughout my life. Because of my knowledge of the true story, I’ve never been able to look at Badlands objectively. As a result, I’ve never been able to really appreciate Badlands the way other people do, but I do appreciate Terry. And the reason I appreciate him is because he didn’t pretend that he was making the actual story into a movie. He made up a fictional one with his own vision, and removed the names of the real people from it. He did this out of a sense of responsibility, something that is sorely lacking in Hollywood. I’ve always valued the fact that he believed that, since he wasn’t making the true story, it wouldn’t be right for him to pretend that it was the true story.

I just thought of a quote I would like to give you, because this sort of sums up my feelings about my involvement with the movie throughout my life. Because of my knowledge of the true story, I’ve never been able to look at Badlands objectively. As a result, I’ve never been able to really appreciate Badlands the way other people do, but I do appreciate Terry. And the reason I appreciate him is because he didn’t pretend that he was making the actual story into a movie. He made up a fictional one with his own vision, and removed the names of the real people from it. He did this out of a sense of responsibility, something that is sorely lacking in Hollywood. I’ve always valued the fact that he believed that, since he wasn’t making the true story, it wouldn’t be right for him to pretend that it was the true story.

The following is an excerpt from Pro Bono:

“Years later I was having dinner with Terrence Malick at Warner Brothers. I was developing a film of my own, and he was finishing his first movie in twenty years, The Thin Red Line. He and Martin Sheen had remained friends of my family ever since they made Badlands. As we walked through the parking lot afterward I told him the story about the “historian” who had believed Terry’s movie as fact and was claiming that Caril Fugate was my mother. I began laughing, but Terry got a very serious look on his face.

“He was silent for a moment before he finally said, “I wonder if it was a bad idea for me to make that movie.” He went on to say that he had sometimes wondered over the years if in making that movie he had done more harm than good. I knew exactly what he was talking about. Most people would be too oblivious to consider the effect their art would have, but not Terry. He is a deeply moral man who considers everything that might result from his actions. And I had wondered myself how many people, knowing the film was inspired by Caril and Charlie’s story, had seen it and mistook it for the real thing. I had always been glad for my connection to this classic film, which in many ways had encouraged me to take the path of filmmaking myself. But I believe what Terry was thinking at that moment was the very thing I had thought about many times. Was it worth it? At what cost do we make our movies, our books, our songs, and our plays, and what responsibility do we have to the truth, and to the results of our efforts? Despite the positive impact of Murder in the Heartland, a week after it aired there was a copycat murder spree in Canada by two teenagers who were inspired after they had watched the TV movie.

“I told Terry as best I could that he shouldn’t worry about it; that it had no real negative effect, and he should only be proud of his work. I was being honest . . . well, mostly, but I knew that I wasn’t getting through to him. Not completely. He would continue to worry about it, and that’s what makes Terry so special; he not only makes great movies, he considers how they are affecting people long after they’re done. That’s what sets him apart and makes him unique in Hollywood, because he does consider the philosophical and emotional consequences, as he should . . . as all artists should.”

Leave a Reply