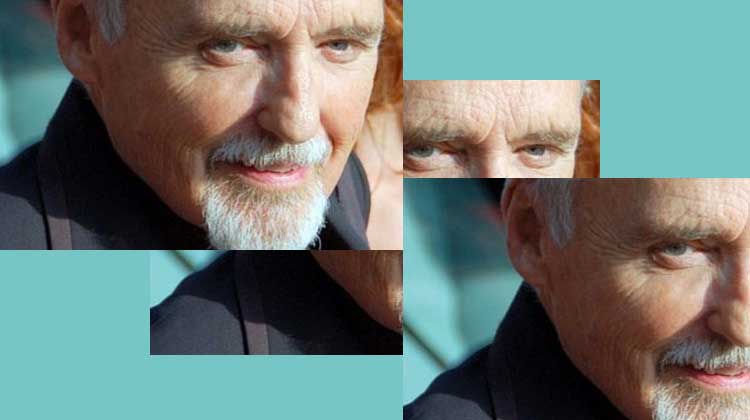

Dennis Hopper’s extensive filmography is filled with an array of painfully bad films. His early career saw him appear in any number of B-Movies and exploitation flicks; his late eighties/early nineties excursion into mainstream blockbusters such as Super Mario Bros (1993) and Waterworld (1995) were undeniably poor; and from the late nineties and beyond, his backlist of movies throw up an assortment of forgettable direct to video/DVD and television movies. Despite this, Dennis Hopper was a legendary and much-respected actor, director and artist; his poor acting decisions did not tarnish his status, and even the films which should, in theory, be banished forever, are worth a screening for the scenes in which Hopper fleetingly appears. His reputation remains intact for a simple reason. He appeared in, or in some cases, directed five films that defined the decades of the last fifty years of the 20th century. These five films epitomise the times in which they were made, reflecting both, socially and politically, five distinct eras, and reflecting also, the ever-changing circumstances of Dennis Hopper’s life.

The Fifties: Rebel without a Cause

In 1955, and still an unknown in Hollywood circles, Hopper was cast as a thuggish gang member in the seminal teenage rebellion film Rebel without a Cause. This was not a Dennis Hopper movie; it was very much a vehicle for the immaculately cool James Dean. Whilst Hopper’s young hoodlum Goon may not be important within the context of the film, the influence that James Dean asserted on the young Hopper had an immense impact on the rest of Hopper’s film and artistic career. Dean introduced Hopper to Method Acting, a realist form of artistic expression that Hopper devoutly continued to follow for his entire career.

In 1955, and still an unknown in Hollywood circles, Hopper was cast as a thuggish gang member in the seminal teenage rebellion film Rebel without a Cause. This was not a Dennis Hopper movie; it was very much a vehicle for the immaculately cool James Dean. Whilst Hopper’s young hoodlum Goon may not be important within the context of the film, the influence that James Dean asserted on the young Hopper had an immense impact on the rest of Hopper’s film and artistic career. Dean introduced Hopper to Method Acting, a realist form of artistic expression that Hopper devoutly continued to follow for his entire career.

After James Dean’s untimely death only a few months after Rebel was released, Dennis Hopper continued his acting studies with the renowned acting tutor Lee Strasburg in New York. Hopper, in effect, seized the artistic career of which Dean was robbed, making him stubbornly determined to utilise the Method at every opportunity. Because of this, he became a nightmarish prospect to direct, and accordingly, was ousted from mainstream Hollywood and left to wander the wilderness of B-Movies and biker flicks. That is, until one particular biker film changed cinema.

The Sixties: Easy Rider

The sixties seemingly brought to America a never ending summer of good drugs and free love. In reality, the decade was a complex game of war and peace; life and death, hope and hopelessness. The Age of Aquarius was drowned out by the gunshots that killed Rev. Martin Luther King JR, President John F Kennedy and his younger brother Senator Bobby Kennedy. In 1962 the world was almost obliterated by the nuclear posturing of the Soviet Union and America, with the Cuban missile crisis threatening to turn the stale mate of the Cold War into a heated conflict. American involvement in the Vietnam War escalated, but socially the decade made some progress. African-American civil rights movements, gay rights and women’s rights began to be seriously addressed. The decade is fondly remembered, but carries with it, a great deal of societal baggage.

The sixties seemingly brought to America a never ending summer of good drugs and free love. In reality, the decade was a complex game of war and peace; life and death, hope and hopelessness. The Age of Aquarius was drowned out by the gunshots that killed Rev. Martin Luther King JR, President John F Kennedy and his younger brother Senator Bobby Kennedy. In 1962 the world was almost obliterated by the nuclear posturing of the Soviet Union and America, with the Cuban missile crisis threatening to turn the stale mate of the Cold War into a heated conflict. American involvement in the Vietnam War escalated, but socially the decade made some progress. African-American civil rights movements, gay rights and women’s rights began to be seriously addressed. The decade is fondly remembered, but carries with it, a great deal of societal baggage.

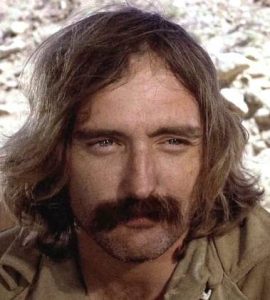

The movie that perfectly captured this schism was Easy Rider (1969). Easy Rider stands as a milestone in American New Wave cinema. The film allowed the New Hollywood ethos of auteur movie making to fully mature. The narrative of two hippie drifters chasing and failing to grasp the America Dream spoke volumes about where America was at, and, where it was heading. Despite the quest for freedom, Easy Rider’s undertone personifies the improbability of living in a truly free society. Against this dour subtext, the film’s visual beauty and vibrant colour make the heart ache with joy. The soundtrack, which incorporated popular rock and folk songs of the time, works as a cultural commentary to the visuals and mood of the film.

Dennis Hopper instantly knew that the sixties’ utopian vision was a lie, and Easy Rider reflects this as the character of Wyatt (Peter Fonda) regrettably admits that “we blew it.” Within the internal framework of the film, what they really blew was their own ideals and principles, but in a social context, Wyatt/Fonda is aiming his words at his own generation who had a shot at creating a new enlightened world but didn’t have the courage to see it through. Easy Rider told the audiences in no uncertain terms that would become a nightmare.

The Seventies: Apocalypse Now

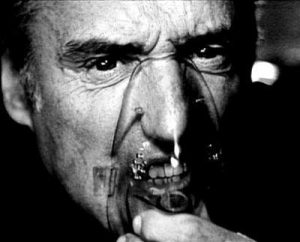

The Seventies saw Easy Rider’s cultural predictions come true, and Dennis Hopper’s role as the jittery Photojournalist in the epic, Apocalypse Now (1979), was the definition of a sixties’ burnout. Loosely based on Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness, director Francis Ford Coppola transferred the setting from the colonial Congo of the late 19th century to war-ravaged Vietnam of the late sixties. Martin Sheen’s protagonist Captain Benjamin Willard journeys the Nung River in search of Marlon Brando’s once distinguished, but now completely insane, Colonel Kurtz. After a few hours of Sheen’s philosophical voice over, erratic gunfire and a surreal scene involving Playboy bunnies, the film comes to a standstill outside of Kurtz’s imperial compound and Hopper’s hyperactive photojournalist makes his grand entrance with the superb line: “I’m an American!”

The Seventies saw Easy Rider’s cultural predictions come true, and Dennis Hopper’s role as the jittery Photojournalist in the epic, Apocalypse Now (1979), was the definition of a sixties’ burnout. Loosely based on Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness, director Francis Ford Coppola transferred the setting from the colonial Congo of the late 19th century to war-ravaged Vietnam of the late sixties. Martin Sheen’s protagonist Captain Benjamin Willard journeys the Nung River in search of Marlon Brando’s once distinguished, but now completely insane, Colonel Kurtz. After a few hours of Sheen’s philosophical voice over, erratic gunfire and a surreal scene involving Playboy bunnies, the film comes to a standstill outside of Kurtz’s imperial compound and Hopper’s hyperactive photojournalist makes his grand entrance with the superb line: “I’m an American!”

What Hopper achieves with this minor role is inspired. He violates the screen with his rapid-fire, thousand-thoughts-a-second ranting and raving, his expressive hand movements forcing the audience to comprehend every last syllable of pseudo-philosophical rambling. Hopper adds an injection of lunacy that invigorates the film. The photojournalist distils the utter madness of war, and he is, in essence, the very definition of post-traumatic stress disorder. Hopper’s character is haunted by war and conflict, and his escape from frontline reportage has meant that now the war is internal. This was true of Hopper himself, whose ravaged and glassy-eyed appearance was reflective of an internal conflict with drug and alcohol abuse. There is no distinct line drawn between actor and character. Both are one and the same.

The Eighties: Blue Velvet

After a number of years ostracized by Hollywood, a newly clean and sober Dennis Hopper made a triumphant return. Hopper’s performance of seething anger and childish brutality in Blue Velvet announced to all and sundry that he was back in rude form. Set in the small leafy American suburb of Lumberton, Frank Booth’s chilling appearance reveals a dark and dangerous underbelly of American society that the naïve, voyeuristic teenager Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle McLachlan) descends into. Films of the Eighties often portrayed teenagers as over-privileged rich kids, whose lust for danger never seemingly had lasting consequences. Even the supposed delinquent kids in films such as The Breakfast Club (1985) and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986) came from relatively middle-class happy homes and eventually achieve redemption in the eyes of their peers and elders. Jeffrey Beaumont would ultimately pay the price for all those mischievous adolescents of the eighties era. Jeffrey’s coming of age would be a devastating loss of innocence. This loss would be at the hands of Frank Booth’s psycho-sexual impulses.

After a number of years ostracized by Hollywood, a newly clean and sober Dennis Hopper made a triumphant return. Hopper’s performance of seething anger and childish brutality in Blue Velvet announced to all and sundry that he was back in rude form. Set in the small leafy American suburb of Lumberton, Frank Booth’s chilling appearance reveals a dark and dangerous underbelly of American society that the naïve, voyeuristic teenager Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle McLachlan) descends into. Films of the Eighties often portrayed teenagers as over-privileged rich kids, whose lust for danger never seemingly had lasting consequences. Even the supposed delinquent kids in films such as The Breakfast Club (1985) and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986) came from relatively middle-class happy homes and eventually achieve redemption in the eyes of their peers and elders. Jeffrey Beaumont would ultimately pay the price for all those mischievous adolescents of the eighties era. Jeffrey’s coming of age would be a devastating loss of innocence. This loss would be at the hands of Frank Booth’s psycho-sexual impulses.

Blue Velvet allowed a change in perspective for audiences who embraced the avant-garde ideals of David Lynch and those that would follow.

The Nineties: Speed

The one negative to Blue Velvet’s excellence is that from this point onward, Dennis Hopper was stereotyped into roles which required him to menace and yell at high decibels. This pigeonholing is encapsulated in the nineties action blockbuster Speed (1994). Speed served to redefine the action film genre. Whilst the eighties action film claimed a fantastical, unreal element, with films such as Terminator (1984), Predator (1987) and Die Hard (1988), containing otherworldly dangers to be vanquished by seemingly superhuman and ultra-fit heroes, the nineties brought in a more realistic, gritty action film, steeped in the everyday mundane and relishing in the pre-millennium anxieties of ordinary people.

The one negative to Blue Velvet’s excellence is that from this point onward, Dennis Hopper was stereotyped into roles which required him to menace and yell at high decibels. This pigeonholing is encapsulated in the nineties action blockbuster Speed (1994). Speed served to redefine the action film genre. Whilst the eighties action film claimed a fantastical, unreal element, with films such as Terminator (1984), Predator (1987) and Die Hard (1988), containing otherworldly dangers to be vanquished by seemingly superhuman and ultra-fit heroes, the nineties brought in a more realistic, gritty action film, steeped in the everyday mundane and relishing in the pre-millennium anxieties of ordinary people.

Hopper’s character as a once-honest-bomb-disposal-expert-turned-terrorist, Howard Payne, is no stretch for Hopper’s method acting skills. However, it threads perfectly with the generic persona of action movie bad guys. The unseemly evil intent of world domination or revenge is neither properly explained nor justified: these guys are just bad, plain and simple, and that means they have to be stopped by the good guys, no matter the cost to the cities they often demolish, and the innocents they indiscriminately kill, in order to snare them. Speed works because it is executed right and played for dumb kicks; it is not high art and perhaps not the definitive film of the nineties, but it certainly operates within the definitive genre and should be counted as a significant piece of modern cinema.

Dennis Hopper defined the post-war American century by embodying the essence of each decade and following a thread of the collapsing American dream. The young and impressible fifties teenager leads to the buoyant hippie of the sixties, then to the bewildered and damaged relic of the seventies then to the indulgent psychopath of the eighties, then finally the destructive maniac.

Leave a Reply