Not that it would make any difference. But if only for the sake of morale, you are willing to admit that it’s a welcome shade of orange that breaks east at the horizon of what has been a roughandtumble one hell of fucked up night. A dull weariness works on your bones, your mind swirls in and out of a strange daze that threatens to rot you from within, and frankly, you’d rather come under the wheels of drunk speeding car than run into someone you know. You are caught in the devil’s tangle. So you weren’t such a bad guy but surprise-surprise- the ways of the world are truly strange. No sense breaking your head over it. You bet your very sanity on the cheap bottle of booze which you had the good sense to tuck in. Just park yourself on a bench in the last light of the streetlamps and drink. You’re not a tough guy. You’re afraid of the cops. The municipality. Neighbors. Relatives. Old teachers. Mongrels. But what have you got to lose?

Bitter gulp by bitter gulp, you gradually disconnect from the reality of the world. The lipstick rouge angel whores of whisky seem to work on and soothe your fear of shadows, the memories of the past night- it all appears rather absurd now…and then one of them whispers a tune in your ear. You begin to whistle it. The dawn has not yet cracked full and at this quiet heady twilight hour, nothing could be more apt than this one melody- the broken man, his unredeemably damned soul, lost love, first spring, long gone dead friends, steam engines, dried leaves, yellow pages, the ache of the heart, first kisses, stolen moments, neon signs rippling in rainy day puddles, lonely cinema halls and lovers taking their last breaths in each others arms. The sweet sweet angel whores of whisky are working incessantly at the strings of your heart- the centre of the warp in which you have descended into. Meanwhile, the sky up there takes on mellow palate and as you whistle the song on and into the morning breeze, gradually begins a slow dazzle of orange, red and around five shades of violet. A quiet jet makes its way across; anointing the dawn with two steam trails that stay put and are inseparable long after the jet has disappeared into another corner of the world.

Back on the streets, the milk-man makes his way past you gently nodding his sleeping head and timing it with the slap of his slippers and to your tune. The first train dashes across in a light-noise blur. Its shuffling rhythms fill your soul, blending with that melancholy song that connects you and the dawn. The city stirs slow, the earth, weightless in space, rotates you towards the sun, and for once, you get the rare sense that nobody is trying to get anywhere in a hurry. Early officegoers, school children, newspaper men, reluctant joggers- all have the gentle melody of your whistle in their gait.

And suddenly, in a moment of clarity that comes into your mind sideways, you realize that you have long since stopped whistling. Maybe you never whistled at all. You almost blush warm as the silence of the moment descends upon you. A most strange silence, this- deep, peaceful, solitary yet with that whistled ballad of yours, of life itself resonating within. Just as you try to comprehend the mystery of that extraordinary song, the last of the whore angels appear and saves you from entering back into the world, from the terrible affliction of consciousness. “You wouldn’t want to do that sucker,” she winks. And with a fond kiss, puts you to sleep with dreams of endless meadows and clouds changing shapes and a world without clocks- all set to the mysterious sound of silence.

A world not unlike the films of Jim Jarmusch.

The Jarmuschian is a beautiful oddity in cinema. For someone who stumbles inadvertently into his movies, they would find themselves hard-pressed to locate the time and space from whence his images come from. Almost at once they seem to be located in the gritty chiaroscuro of the 50s roughandtumble B-movie noirs and the transcendental stillness of masters Ozu and Bresson while also in the absurd irreverence of early Godard and yet there is more. There is that eccentric vision- cool, deadbeat, hipster that is pure Jarmusch. Somewhere between Rififi‘s pindrop silent highwire heist sequence, the meditative trance of a Ozu take and Godard’s quip of ‘a minute of silence’ in the café in Band of Outsiders lies the Jarmuschian- age old yet thoroughly modern, and as a sum of so many parts, absolutely original and timeless.

A Jarmusch image is trademark sparse- in composition, movement, palate, dialogue and sound but the sparseness and inherent stillness is heavily inspired and stylized. Long static takes are filmed with an eye for that hipster chic and characters and objects and landscapes blend in a precise scheme of utter ‘cool’. These obsessive precision cool long takes are edited along a most unorthodox even vague narrative thread that begins in mid-air and spends the ninety odd minutes unspooling in a ellipsis that has a tendency to frequently fold in on itself and then ends, again in mid-air without straining for the least bit of resolution of any sort. With the combination of the unerring cool of the mis-en-scene, the static takes and the deadbeat narrative- the film can decidedly be viewed as an exercise in style above all else and ever so often one will come across reviews discussing Jarmusch films purely as a study of design and structure both in shot composition and as a narrative. To view the film as some sort of study in still life tableaux is to miss out or rather misconstrue the most essential element of a Jarmusch film, even the Jarmusch image- the silences.

Jarmusch has acknowledged the influence of the New York School of Minimalism on his aesthetic. Less is more. Nothing is a something. Zero is a value. Quite like his spare color schemes, he operates in subtle nuances of silence. It is the silences that free the Jarmuschian narrative from the constraints and oppression of time and rigidity and renders it into free-flowing poetry. The silences can be of myriad shades- contemplative, melancholy, tedious, repressive, perplexing or even an inordinately long absurd pause before delivering the punch line for a running joke. Also carved from silence is that air of mystique around his film that is better experienced than put in words. Watching a Jarmusch film, one is acutely aware of eccentric vibes coming from the film but while there are times when they leave you confused and times you connect with them but the best of it all is when you catch yourself quietly reacting to a scene that has long gone by and you find that before you even knew it, the film has strangely double backed on itself.

Down by Law (1986), Jarmusch’s third after Permanent Vacation (1980) that got him thrown out of film school and Stranger than Paradise (1984) his breakthrough Camera D’Or winner, begins with a series of long pans, set to a Tom Waits melody riffing about dead-end lives in no-good towns, from the right to the left along the streets that are decidedly familiar but at once strange. Looks like a end-of-a-line town of sorts, American but exotic, even ancient. Seems like you’ve seen it before, in a faded photograph or a movie that exists in your memory.

We first see Jack (played by artist, singer, actor John Lurie who apart from being a frequent collaborator on Jarmusch films, scoring the staccato fake jazz on the soundtrack, and who also did the terrific Get Shorty score) sleeping with a waif-like striking black girl before he gets up, trudges to the door and sees a girl sitting outside who tells him that she’s watching the light change. He comes back to bed and the black girl, sleeping with her back against him, opens her eyes and looks blankly ahead.

The song kicks up and the camera pans again. This time from right to left. All the way across town.

We see Zack (singer-songwriter-legend, last of the beat poets and inimitable actor Tom Waits) enter a ramshackle room and lie down besides his girl-friend, Laurette (Ellen Barkin). With her back to him, she opens her eyes and with hurt and longing stares into the camera.

Song kicks up. Camera pans. And with the deadbeat absurdity that Jarmusch seems to enjoy infusing in his title sequences, they begin with austere style, white letters against black background against the sounds of a lonesome dead end town night.

Post-titles we first witness a bitter and prolonged fight between Zack and Laurette. He has just lost himself another job as a RJ just as they were counting on it to settle down and it’s driving ol’ Laurette up the wall. She’s flinging his record collections outside the door while he just sits put mumbling drunk without coherence and conviction until she decides to fling his favorite pair of shoes out when Zack finally decides that she’s gone too far, breaks up with her and leaves. We’ll never see her again but her lost gaze when she first opened her eyes, you will remember with melancholy and meaning. Meanwhile at Jack’s place, the black girl is still in bed- reclining, berating Jack, her pimp, for thinking constantly about a glorious future that he fails to see the shambles of the present. Jack is pretty much thick-headed about her rambling. Soon enough, a fat hustler comes over to his place and promises him a Cajun Goddess as a goodwill gift and they leave. We’ll never see her again but her lost gaze when she first opened her eyes, you will remember with melancholy and meaning.

Without any effort at exposition, without making the least fuss, in perfect silence Jarmusch sketches two lowlifes or at least he gives us a silhouette of two sympathetic lost assholes and asks us to improvise. The art of jazz masquerading as a film.

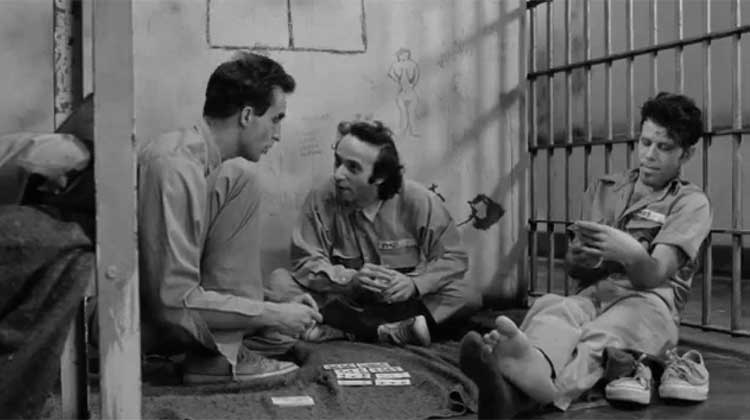

Soon both Jack and Zack find themselves set up as fall guys playing inadvertently straight into the hands of law and end up locked in with only each other for company in the same cell. The inability/ability/difficulty of people to relate to each other via language and culture is a major and recurring Jarmusch theme. Jack, habitually tries to find solace in delusions of a glorious future where as he puts it, the luxury of a swanky car and four naked girls await him while Zack takes to a silent brooding, marking each day on the wall in lines and crosses, a system of counting which he doesn’t really comprehend if you look at the unevenness of his symbols but still probably does it because that’s what the movies have taught him to do. There are stray moments where they connect with each other but these moments dissipate into ennui and after so much comic loggerheading they finally break into a scuffle that threatens to forever break what little ties exist between them dooming each to the eternal boredom of his own solitude. The joke, of course, is that Zack is supposed to be a radio jockey.

Just as Jack and Zack reconcile with the bleakness of their situation, Jarmusch introduces yet another recurring motif- the foreigner in America who in all his naivety still has a better and more profound understanding of humanity and even America and its culture than the Americans themselves. In ‘Down by Law’, the character is played with an almost neurotic always-excitable combustible zest for life by Italian actor-director Roberto Benigni as the Italian tourist, named fittingly and perhaps almost as a tribute, Roberto. The scene where he first enters the cell where the two Americans sit in silence and almost unshakable hopelessness and reads out from his scrapbook of collected American phrases is a scene of such brilliant sophisticated comedy hardly witnessed in cinema. It’s a classic example of Jarmuschian humor- silent, prolonged, absurd even proudly silly but still gets you at gut level leaving you with hardly enough time to grasp what just hit you.

Despite all of Roberto’s exuberance and efforts in trying to get a conversation going the Americans keep cold-shouldering him. Roberto allows the two to call him as ‘Bob’ while the Americans keep getting annoyed each time he mixes up their names. Bob talks of Walt Whitman and Leaves of ‘Glass’ but the Americans will hardly acknowledge him. He draws a window on the walls of the jail cell but Jack glumly tells him it’s a window you look ‘at’ not ‘out’. But not that it dampens any of Bob’s spirit. His incessant efforts at working up mischief and excitement finally reach a crescendo when his chant of ‘I scream, you scream, we scream for ice-cream’ becomes a sort of absurd life-affirming anthem of resistance and rebellion not just within the cell but reverberates within the walls of the whole prison. And pretty soon, Bob also thinks of a way to escape from the prison ‘just like in the movies’.

The prison break in never shown on screen. We just witness the three men in jail clothes running through the swampy mysterious bayous of Louisiana. The chasing police are never witnessed nor do we know how the fugitive trio manage to find a boat. There are other movies who will do exactly that for you. Jarmusch’s concerns are with showing three men lost in the middle of exotic nowhere, running around in circles with no direction home, scared of being apprehended at ever turn and having only each other to trust.

Zack and Jack continue to insist on being apprehensive of each other and aloof from Bob but the sprightly Italian refers to them as friends and naively continues to believe in their companionship. Like the characters who are unable to escape the strange bayous, the narrative also finds itself circling a fixed spot and gradually, existential concerns enter the firmament of the film.

For all of Bob’s scene stealing, it dawns back on us that this is a movie about Jack and Zack.

Jack is a dreamer. He lives in a delusion of a glorious future that we realize might never come. He is a man in love with his own lies, concocted perhaps to escape the shambles of the present but gradually he has got himself addicted to them. He is a hustler but unlike a good hustler, is too full of delusions and of himself and maybe, even too good by way of heart to hustle any kind of success.

Zack too is a dreamer. But unlike Jack his crisis is mostly spiritual in nature. He knows his Walt Whitman, he seems to know his culture but his soul is warped with delusion. He once had a glorious vision of his future, something righteous maybe, but now, has lost it along the road and now, wallows in the pain and ennui of its loss.

Bob is the straight arrow. The ‘good egg’. His is the character we all root for, we relate to. He has an infectious exuberance and plays clown and simple even as he is profound. His demeanor is childlike even innocent.

As the movie takes on an increasing fairytale structure in the swamps one recognizes in Bob the ‘inner child‘. In this high-spirited outsider, Zack and Jack, two disillusioned souls find a part of their lives, their souls that they have lost somewhere along the road they picked on to travel to their respective dreams. Their cold-shouldering of him seems to be nothing but their inability to articulate or to face up to the fact that the delusions in which they are living are wrong. It is the beautiful philosophy of the beat poets, of Kerouac, of Ginsberg, of Snyder that informs Jarmusch’s own poetic spectacle- rebellion from the drab ordinariness of everyday life, realizing the purity of a child’s view of the world, hoping for a return to innocence and to infuse the present, the now with mad, insane, over-the-brim zest for life. Bob himself with his absurd notebooks, strange speech and love for Whitman may not necessarily be a poet but he is certainly qualifies as a beat.

But Jarmusch offers no easy resolutions. Doesn’t intellectualize. No pontification. Doesn’t try to fill the cup at your core with an honest-to-goodness milk of life. All he’s done is given you a vessel the size of your soul.

The three men separate. Bob opts out first. Zack and Jack proceed to the point where the road splits into two. Each strand seems to stretch into the horizon and lest assured, the twine will never meet. They bid goodbye. Maybe there’s an faint acknowledgment that their time together has had an impact on their lives, that it was all indeed, a time to remember. But you never know, there is a lot of road ahead to travel yet.

Jarmusch decides that’s all there is to know. Fade to black.

The films of Jarmusch invite all sorts of comparisons with those of Fuller, Peckinpah, Ozu, Bresson, Wenders, Godard, Ray but these are primarily his influences which he channels into a craft of his own. Finnish master of droll Aki Krausmaki is a valid comparison, a contemporary and close friend of Jarmusch and yet another director that operates on the same deadbeat lowlife wavelength. Among the next generation Thai auteur Pan-Ek Ratanurang (Last Life in the Universe) and Mexican genius Fernando Eimbcke (Duck Season) can lay claim to Jarmuschian traits. But in a strange almost tangential way, Jarmusch reminds me of David Lynch. Superficially they cannot be more disparate- Lynch’s nightmarish concocts and Jarmusch’s cool composed visual poems. But to get to the heart of their films, the viewer has to enter the film-maker’s very personal world on their own terms. Both directors, fiercely and adamantly independent, create labyrinths out of signs and symbols that they have made their own into which the viewers have to make their way through. Where Lynch is button pusher, the Jarmuschian world is more relaxed allowing the viewers to put in a yawn, doze off or even drift away into thoughts of your own.

The Jarmuschian maze is intricately laced and laid out. The entrance is common but within the labyrinth you lose the company of others and wander lonely in ‘sad and beautiful’ passages and each one finds his own way out. The experience is solitary. Like wandering empty streets at night drunk on cheap liquor and watching the dawn gently break through thick smoke.

What a feeling…