I guess it’s appropriate that blockades have gone up again on the Tyndengia Mohawk reservation in South Eastern Ontario Canada as I begin to write this review. Here in Canada the First Nations people are usually out of sight and out of mind unless they manage to capture the media’s attention with some event which inconvenience the population at large. While the fact that the majority of them live in conditions equivalent to the destitution most in the developed world equate with the poverty of the developing world should be news enough in itself to keep them in the papers on a daily basis, we only read about them when anger and resentment over conditions reach the boiling point and spill over into angry protest.

Last winter’s Idle No More grass roots movement pushed First Nations issues into the spotlight temporarily, but the government has done its usual good job of simply ignoring them, understanding that if they say nothing the media will soon move on to something else. Canada, and by extension North America, aren’t unique for their mistreatment and ignoring of the indigenous populations whose lands we now occupy. Around the world, from the South Pacific to the High Arctic, indigenous people are marginalized, starved, pushed off what little land we leave them and generally continue to face bleaker and bleaker futures while nobody seems to give a shit. We give them the worst land available and then pollute or steal it when we discover natural resources beneath it ripe for exploiting.

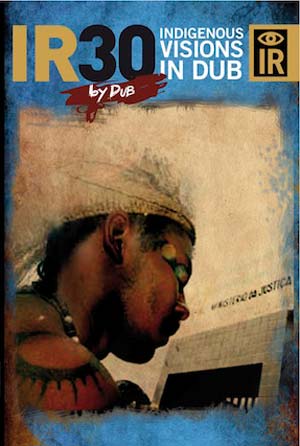

A number of years ago I had reviewed one of the earlier recordings on the IR label, but somehow or other I lost track of their releases over the years. Which is what makes this book all the more interesting and valuable. For the texts they’ve selected to include not only deal with the major themes and stories from the indigenous world they’ve been trying to cover over the years, they also bring the words of some of the more insightful minds among indigenous people together in one volume.

Like the recordings, the words gathered in this book come from all parts of the globe. They’ve included lyrics/quotes from musicians from the Solomon Islands (Tohununo and Pesio), stories about an incident which occurred in Brazil where an indigenous man was burnt alive by four wealthy youth (who received only minimum sentences), articles exploring the ties between the indigenous people of North and South America and African Americans, and quotes from two of the most interesting minds among the North American indigenous population, architect Douglas Cardinal and musician/poet/former chair of the American Indian Movement (AIM) John Trudell. While the story of the murder of the Pataxo Galdino in Brazil is sickening in the way it reflects the indifference of the Brazilian population at large to the indigenous peoples whose land the Portuguese stole it makes valuable reading, if only for the contrast it provides to how we normally see these people. Instead of being gaudily dressed props for pop stars’ photo opportunities, these are flesh and blood people barely eking out an existence in some of the biggest and roughest slums in the world.

To my mind, the most fascinating readings in this book are the quotes from Douglas Cardinal and John Trudell. Cardinal’s words on the nature of power and the way women are treated are stated so matter of factually it makes you wonder how anyone could act any differently. On women, he sums things up very succinctly, “One has to state that all the premises that men have of women are basically wrong and you start from there. Even the language is wrong”. He uses the same directness of language in his discussion on the nature of power, “I have learnt…that the most powerful force is soft power, caring, and commitment together. Soft power is more powerful than adversarial or hard power because it is resilient”.

Trudell’s words resonate with a different kind of power. He is someone who knows the power of the mind and the power of words (The FBI once referred to him as one of the most dangerous men in America simply because of the power of his oratory). In a poem quoted in the book, he speaks out against the frameworks of European society imposed upon his people as being the instruments of their destruction. Why should he support purported democracy when all it has done is make of his people (along with African Americans and women) second class citizens who are treated like chattel? “We live in a political society/Where they have all power/by their definition of power/but they fear the people who go/out and speak the truth”.

Our governments give occasional lip service to the plight of Native Americans and Canada’s First Nation’s people, but their policy of doing nothing and hoping the problem goes away has now become official. New acts passed in both the Federal legislations of Canada and the US are designed to ensure the numbers of registered, or status, indigenous people decline to the point where they can take back the reserves and reservations because there will no longer be enough “Indians”. Yet anyone who dares speak this truth is called paranoid and deceptive. Who in fact are the more paranoid and deceptive – the ones cynically trying to get rid of “The Indian Problem” or the ones who are the subject to these draconian laws? (For anyone interested in reading about these new acts I recommend Thomas Kings’s The Inconvenient Indian.)

From the Sahara Desert to the Australian Outback, the rain forests of Brazil to the tundra of Siberia, the Black Hills of Dakota and northern Alberta Canada indigenous people are seeing the land promised them by treaties gradually stolen away from them. What lives they’ve been able to carve out for themselves in this post-colonial world are gradually being eroded and destroyed. Their culture is appropriated and turned into a commodity, they are depicted as stereotypes, not humans and more and more government policy is being directed towards their destruction as distinct societies.

One of the few means at their disposal to remind people they are living breathing cultures is to find the way to speak with a unified voice – one that is loud enough to be heard around the world. Through their record label IR, TFTT is doing its best to provide the opportunity for those voices. IR 30: Indigenous Visions In Dub gathers together some of the most powerful words and images used during the creation of the label’s 29 recordings in a single volume as an intense collage of ideas and visuals. It offers a far different perspective on indigenous life around our planet than that offered by either governments or your New Age bookstore. Isn’t it about time you read the truth?

Gara says

Fantastic, info-filled review! Shared w/ my daughter.

I want this book! BUT, does it come as a Hardcover, hold-in-hands “real” book?

I don’t do Kindle. I’m a book person.

Thank you,

Gara

Denise Enck says

Hi Gara,

I know what you mean! I strongly prefer printed books, too. Fortunately, IR 30 is available in paperback. If you click the link at the end of the review, it’ll take you to the book’s page on Amazon. Under “Formats” you can click “Paperback” to buy that way. Enjoy!

cheers –

Denise