DADIO SPLIT FOR MOLOKA’I every weekend to supervise his Puko’o project. He was certain his pick-and-shovel laborers and heavy equipment operators were slacking off. I took turns with Troy, my big brother, serving as his assistant. We carried luggage, accompanied him on his lagoon inspections, and served as whipping boys should he need to vent. I hated going. I always thought he saw his half-brother in me. Uncle Bobby managed the Barefoot Bar at Queen’s Surf and my father said Bobby “drank like a fish” and chased the cocktail waitresses. He considered his younger brother a loser ever since flunking out of Saint Louis High. It was tough living in Dadio’s world because, once his negative opinion of you was formed, you were tainted for life. I couldn’t think of a single person in our extended family that he liked or ever praised. But he did have a soft spot for DuBoy, a legally blind cousin and bastard child of his Aunty Sue.

*

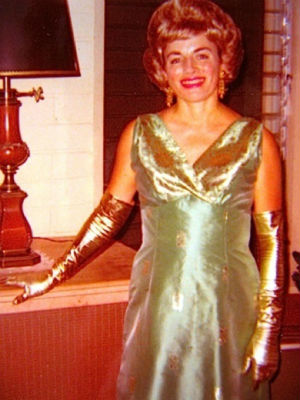

If it were my turn to remain in Honolulu, I’d catch my mother singing and tapping to show tunes playing on the radio. Her singing and tapping had a purpose—the girl inside was searching for that spark of hope the woman had misplaced. The use of voice and limbs fired up her optimistic nature and her face took on a vibrant glow that made her appear younger. I recognized what had intrigued my father back in Boston. My mother bore a resemblance to Rita Hayworth and had a beauty mark like Marilyn Monroe. There was a star quality about her when she was happy, as if she were strolling the red carpet at a premiere. I felt bad she wasn’t a star.

*

It was Friday and my father had just left for Moloka’i with Troy. The house seemed a happier place without them. I was the man of the house and felt a duty to protect my mother and Jen. I’d shortened my kid sister’s name because that’s what her classmates called her at Kahala Elementary and she preferred it.

June Spoon invited Jen and me into the living room. Our mother wore a tailored green muumuu, a string of pearls, and white heels. My sister and I sat on the couch while she recited a Blanche DuBois monologue from A Streetcar Named Desire. She’d once sung “Beyond the Reef” on the Jack McCoy Radio Show and worked as an extra on an episode of Hawaiian Eye. That episode was hard because she was paid to pose as an adoring member of the audience while Connie Stevens crooned, “What’s New?” She thought her voice was far superior to Connie’s.

My mother finished her monologue and bowed.

I clapped like crazy. “A star is born!”

“Oh, go on,” she said.

“Face it, you’re a natural, Mom.”

“Better than Ethel Merman,” Jen added. My sister had on a pink muumuu with a hibiscus print, a gift from an adoring local uncle whose wife couldn’t have children. I knew Jen had already been sucked into our mother’s fantasy world after admitting she wanted to be a rock star like Elton John.

“You know,” June Spoon said, “I feel so alive whenever Daddy leaves.”

Jen waved her hand. “Me too!”

“But why do you call him ‘Daddy?'” I asked.

My mother toyed with her pearl necklace. “Because he’s your father.”

“Yes, but he’s not yours.”

“No. I guess that I shouldn’t.”

“Would you have married him,” I continued, “knowing then what you know now?”

“If I hadn’t married your father, I wouldn’t have all you nice children.”

“Pretend you never had children. Would you have still said, ‘I do?’”

“At first your father was quite the gentleman. He listened to every word I said and treated me to all the best plays and shows in Boston. He even wrote me poetry.”

“He wrote poems?”

“He’d recited page after page of love poems composed on legal pads during picnics on the Charles River. I was sure being with him would make every day of my life wonderful. Harold S. Wright was the best actor I’d ever met.”

“He deserves an Oscar.”

“He certainly does.”

“When did he change?”

“Oh, there were signs along the way. My father called him “that strange fish” and said it was impossible to warm up to him. The big change came not long after you were born, Kirby. I couldn’t understand him hitting you and Troy. I’d never seen anything like that in all my life, and he threatened to hit me for interfering. My mother said he seemed sneaky, like he was trying to hide something.”

“Hawaiian blood?”

“No. It had something to do with his personality, some odd thing she noticed. Thank god you didn’t turn out like him.”

“Still wanna divorce?”

“Let’s wait and see until you and Troy get into college. I don’t want him refusing to pay your tuition.”

It was hard understanding how my mother could live with a man she detested. Our house was her prison. It struck me that, since she faked it as a wife, maybe she was faking it as a mother too. Maybe she thought of her children as props in a macabre play starring a tyrant and his long-suffering wife.

*

June McCormack was raised in the burbs of Waltham, Massachusetts. She was the child of an adoring father who’d made a killing in the stock market during the Roaring Twenties but lost everything in the Great Depression. Pops began coming home late, claiming he was “burning the candle at both ends” to pay the mortgage. Gert, his wife, hired a detective. The detective trailed Pops to the Black Rose Tavern, where he kissed a blonde half his age in a booth. June was ten when they divorced. Pops declared bankruptcy and the Waltham house was sold. Gert won custody and hocked her pink sapphire bracelet to pay rent for a flat in Brookline. The ruby ring was pawned for food. Finally, the cognac diamond wedding ring was sold. June had everything and nothing the first decade of her life. The thing that left a lasting impression was watching her mother board the streetcar that would take her to a teller position at First National Bank.

*

June Spoon was on the lanai leafing through a photo album with a red velvet cover. I sat beside her on the couch. The album contained a collection of tintypes, albumens, and daguerreotypes on paper-thin metal glued onto black pages as thick as card stock. The album smelled of tarnished silver. She studied the images, marveling at how young everyone looked and recalling brilliant fall colors, ice-skating a pond that froze each winter, and taking glitzy trips to New York and east coast hot spots with her parents. She drifted back to a less complicated time, the years of plenty with a powerful father who loved spoiling her. She showed me a tintype of them strolling the Atlantic City Boardwalk. Her mother wore a hat, a mink coat, gloves, and an orchid corsage; Pops sported a camel hair topcoat, fedora, tie, and an ebony cane he seemed to be using more for effect than for balance; between them was a girl clutching a teddy bear. My mother dwelled on black-and-whites of a Tudor mini-mansion featuring a nightclub-sized bar sizzling with notes off a baby grand. Her parents wrapped her in a world of silk dresses, singing and tap lessons, and music. Isabel, the black maid, loved her like a daughter. June Spoon crooned show tunes as Gert’s fingers tickled the keys. Pops had promised her Broadway. She could do anything knowing he’d pull the strings delivering her to the door of fame. Like the plant that can survive on air, my mother continued to nourish her soul by feeding off the fantasies of an indulged girl.

My mother had lost Pops earlier that year. He’d suffered a heart attack after losing a leg to phlebitis and died alone in his Chicago apartment at the Pick-Congress Hotel. The concierge found him in his wheelchair. Sparky, his parakeet, clung to his shoulder. My mother couldn’t stop crying the day the call came in and there was nothing I could do to cheer her up. I wondered if guilt factored into her suffering. She’d seen Pops only twice in the past decade, on stopovers on the way to Boston. Chicago was never a final destination. I guessed she harbored a deep resentment because he’d failed as a provider after the divorce, and failed once again when he couldn’t pay for her wedding at Saint Aidan’s Church in Brookline. I wondered how she reconciled her lack of forgiveness with the teachings of Jesus. By ignoring her handicapped father, she gained a measure of revenge for him abandoning her as a child. It had been his praise and money that fed her dream of stardom, a dream that floundered in Gert’s rented flat. Pops meant everything to June Spoon as a child but nothing to her after the red baby grand was carted off and Waltham became a memory. She’d ignored him as he languished in his wheelchair at a second-rate hotel. I was suddenly aware of my mother’s vindictive nature and realized that, if I ever crossed her, she’d exact a hefty price.

My father tried comforting my mother by handing her a box of Kleenex and patting her shoulder like she’d done a good job at something. He’d never minced words when talking about Pops, calling him “that piker” and “a blowhard.” He left and returned with a bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken for the family dinner. He fixed a Manhattan and placed two breasts, coleslaw, and a corncob on a paper plate. He balanced his offering on a TV tray and carried it into the master bedroom. He closed and locked the door. I pressed my ear to the door and heard my mother sobbing. “Now, June,” my father said, “drink your Manhattan and things will get better, just wait and see.” The sobbing grew louder.

Jen joined me at the door. “Will Mummy ever come out?” she whispered.

I nodded.

My sister slunk off into her room and returned with her pink blankie. She spread it down outside the door and wrapped it around her body.

*

My father’s weekends on Moloka’i gave my mother the green light to phone home. She called her mother, brother, and aunts in Boston. After catching up on their latest ailments and financial problems, she plopped the receiver back in its cradle. “Those poor, poor women.” At dusk on Saturday, she invited us to attend her private concert on the lanai. Jen and I flopped on the couch. June Spoon crooned “Anything Goes” by Cole Porter and the haunting “In The Still Of The Night.” She looked like Marilyn with her platinum wig and yellow cocktail dress. Her gestures and expressions made me think of that little girl performing show tunes for adoring parents back in Waltham. Perhaps, even back then, she feared the Fabergé egg world Pops had created might break, spilling forth dreams into the uncaring universe. I flashed to our first and only cruise on the Lurline. June Spoon approached the microphone in a white dress and white opera gloves. My angel mother sang about a magical land of golden gates and sun-kissed girls in a ballroom filled with strangers, stretching out long arms as if embracing them. Wild applause and a First Place trophy made her believe Broadway was still within her grasp.

My mother asked if we could see her performing in New York.

“Yes, Mummy!” Jen said.

“Off Broadway?” I asked.

“Broadway would be better.”

“You could be Laura’s mother, in The Glass Menagerie.”

“I’d rather be Laura.”

“But you’re a mother.”

“You’re right, Kirby. I’m a fat old woman now.”

“That Star Market cashier said something interesting yesterday.”

“Was it that Violet?”

“Yes. She asked me if you were my sister.”

“I don’t look that young, do I?”

“It’s your Irish blood.”

She patted her cheeks. “Peaches and cream.”

I suggested she try out for Hawaii 5-0. She said she’d heard you had to be “friendly” with the casting director to land a role and launched into a vicious attack of Jack Lord. She claimed Jack never smiled in public, wore a big floppy hat, and failed to offer her his grocery cart after wheeling it out of Star Market. “What nerve,” June Spoon hissed, “that man saw me coming but returned his cart to the rack.” She said he’d been in used car sales and couldn’t be bothered trying with such a rude man running the show.

“Gotta start somewhere,” I reminded her.

“You’re right, Kirby.”

“How ‘bout community theater? They’re auditioning now for Hot L Baltimore in Manoa.”

“That’s full of dirty language.”

“You can’t be picky.”

“Oh, everyone’s so young and talented these days.”

“You look young and you’ve got talent. You just need a break.”

“I should lose a few pounds first.”

My mother’s make-believe world transported her to the crossroads of absurdity and delusion. The sky was the limit and fame was still possible. She’d never abandoned the dreams Pops inspired back in Waltham, visions that survived her lean Brookline years, her agony slaving on the assembly line for Maybelline, and a string of secretarial jobs with cruel bosses. June Spoon’s head slumped. I saw defeat in her eyes and told her she could be as big as Liz Taylor or even Barbra Streisand.

Her eyes brightened. “Not Liz.”

“No?”

“Liz can’t sing.” My mother sat down beside Jen on the couch. She launched into her I Wonder Monologue, her musings on how life would be different if she’d married another suitor. “I wonder about Fletcher Eaton,” she said. She claimed he had to sell two pints of his blood to pay for her dinner at Durghin-Park. She admitted he couldn’t afford her program when they attended a play in Boston.

“Was he the man who got away?” I asked.

June Spoon gazed sadly at the ti garden. “Fletcher invented polyester,” she sighed, “now he’s a millionaire.”

“Does he strap his children?”

“That nice man wouldn’t hurt a fly.”

There were other men besides Fletcher. She adjusted her mood according to each man’s earnings. June Spoon was heartbroken over Fletcher, but her spirits picked up noticeably recalling the BC quarterback who’d been her blind date.

“Good thing I dumped Burt,” she said, rolling her eyes. “Last I heard, that poor man was selling shoes in Southie.”

Later that night, my mother pulled out a honey blonde, applied mascara, and dabbed on blue eye shadow. She squeezed into a white sequined gown and flung a pink ostrich feather wrap over her shoulders. The gown revealed a midriff bulge. “Kirby,” she said, “what shape is my face?”

“Heart-shaped.”

“Mary Robello swears it’s moon-shaped. It’s not moon-shaped, is it?”

“No.”

She patted her belly. “I think she’s jealous of me.”

*

The only kink in our vacation from Dadio was his customary call on Saturday night. My mother answered. “I miss you, Dear,” she told him. I plucked up the receiver of the second phone in the master bedroom to eavesdrop.

“Is Kirby doing his chores?” Dadio asked.

“Yes.”

“Tell ‘im I’ll be inspecting his work.”

“How’s Troy?”

“That boy’s a big help.”

“Did he catch an ulua?”

“Not, but he’s got kaka lines out right now.”

I was glad to be on another island away from my father. I slipped the receiver back in its cradle.

*

After Dadio’s call, my mother and Jen took off to Papa Nino’s pizzeria. They snacked on jumbo hot dogs at Orange Julius, bags of chocolate-covered macadamia nuts at Morrow’s Nut House, and cheese sandwiches at Woolworth’s. They often celebrated their weekend freedom at Farrell’s Ice Cream Parlor. June Spoon seemed more like a binging teenager than an actress and singer worried about her figure.

I lived on Hungry Man dinners. I rebelled by sleeping late and staying up until two in the morning. I got addicted to KORL talk radio and phoned incessantly. Tom Slaughtery, the talk jock, called me “The Kalihi Kid.” I spoke pidgin English and asked if anyone listening wanted to fight. The by-products of my calling gave birth to three new characters—a Portuguese bus driver, a Japanese mama san, and a hooker from Oklahoma. I would dial and redial, switch voices, and have one character slam another. The mama san called to criticize the hooker for selling her body. The bus driver wanted to date the hooker. The hooker told the mama san she was just a working girl and informed the bus driver she’d be at Makapu’u that Sunday wearing a red bikini. I created a soap opera of intrigue. Invariably, another listener would call and racially slur one of my characters. That caused an avalanche of calls from the Portuguese, Asian, and haole communities, with offended listeners either defending or attacking the mama san, the bus driver, and the hooker.

“Nervous breakdown time,” Tom Slaughtery confessed.

“Eat Portagee bean soup,” the bus driver advised.

“You need a long massage,” the hooker offered, “the kama’aina discount’s fifty bucks.”

“Everyone pupule,” the mama san chortled.

* * *

Dadio assigned chores to the son who’d stayed behind in Honolulu. Those chores included turning the garden valves off and on along with a list of tedious tasks, such as hand sanding the garage ceiling, clearing lauahala leaves that had fallen in the front yard, and replacing leaky sprinklers. The minute my father returned, he’d dart to his ti garden and clawed the soil. “Christ,” he’d bark, “this dirt’s bone dry!” He wasn’t pleased unless the soil was the consistency of mud. When I devised a more efficient way to complete a chore, he considered that a challenge to his logic and authority. I’d borrowed Mr. Applestone’s power sander to speed up progress on the garage ceiling.

“Didn’t I say to hand sand, Kirby?” Dadio had grouched.

“Yes, but that power sander made it go tons faster.”

He’d climbed up on the bumper of his Olds and ran his hand over the ceiling. “Why, you sonuvabitch, you gouged this god damn surface!”

“Where?”

“Right here. Right where I’m feeling.”

After he’d gone to bed, I climbed up on the bumper and ran my hand over the area I’d sanded—it was as smooth as glass.

*

My mother wanted to split before Dadio returned on Sunday night. She complained waiting for him was torture so we left to feed the homeless at Saint Andrew’s Priory downtown. I liked it that we were doing something good. Jen handed out plastic spoons. My mother slung scoops of macaroni salad. I ladled beach stew into paper bowls. Father Keelan knew my mother loved entertaining and had her stand on a lava retaining wall beside him. She sang, “If I Had a Hammer” and “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.” A Hawaiian woman asked her if she knew Kui Lee’s “I’ll Remember You.” My mother sang that song with such passion and conviction she made the woman cry.

*

The Olds was in the garage when we got back and the dark cloud that had left the house settled back in. Dadio flung open the front door and said he felt “funny as hell” coming home with us gone. His round face was ruddy with anger. He accused my mother of volunteering only because she liked pretending she was a star, saying she didn’t really care about the poor. But June Spoon had a glow from entertaining and there was nothing my father could do or say to dampen her spirits. Her dream burned with renewed hope that evening, even after Dadio popped the Lancers Vin Rose as his signal he wanted her in bed after Ed Sullivan. Demanding sex made him feel in control. I suppose June Spoon maintained her sanity by believing it was a noble sacrifice for the good of the children. As Dadio sweated over her in the oily moonlight, I wondered if she escaped by imagining she was singing on a stage an ocean and a continent away. But no matter how much she faked it, my mother couldn’t escape the truth that she was living a lie fueled by the false belief love and money were intertwined. She’d failed to understand love could exist without money. When push came to shove, her need for security ruled. She wanted no repeat performance of those lean years when she was forced to leave Waltham.

June Spoon didn’t love my father, although at first maybe she did. But being under the same roof for over fifteen years had fertilized the dark soil of her heart, allowing a seed of evil to take root. Everything good about her had been compromised by the horror of giving in to a brute, the same horror Blanche felt when Stanley raped her. My mother was sleeping with the only man in the world she truly despised.

Nikki Wilkinson says

A work of tragic beauty that made me weep. I will remember this for quite a while.

Sam Silva says

wonderfull poignant and professionally written, as I’m sure the author knows