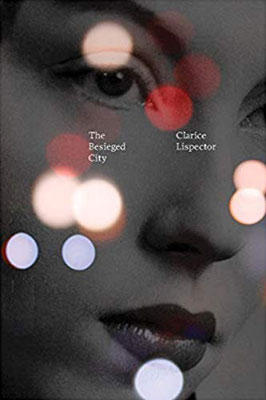

The Besieged City by Clarice Lispector. Trans. by Johnny Lorenz & Ed. by Benjamin Moser

New Directions / Penguin Random House / 2019

Lucrécia Neves “mulls over her inability to reason”; when we look at the world through her, it is transformed — and it transforms. In The Besieged City, Clarice Lispector gives us a woman whose passage from girlhood to maturity we witness alongside the story of a town becoming a city in 1920s Switzerland.

The language of The Besieged City doesn’t simply offer a reading experience that is mesmerizing for some and daunting for others. Through Lucrécia, the words on the page push against the borders between sensing and reading: words become material, palpable, as if we can touch what she touches, see, hear, taste what she perceives, so that the story becomes not only “more real,” or tangible — an advice that you would find in many books and blog posts on “how to write better” — but moves us to imagine reality differently. Lispector invites us to this play of imagination: “So what would she say if she could go, from seeing objects, to saying them … That was what she, with the patience of a mute, seemed to desire.”

This translation by Johnny Lorenz, long overdue as the work was missing in English language since its publication in Portuguese in 1948, is published with a special appendix: a review by Temistocles Linhares which had appeared upon the publication of the novel in 1949, and Lispector’s response to that review written twenty-two years later in 1970. This curatorial choice of the editor Benjamin Moser, author of Why This World: The Biography of Clarice Lispector, is significant in that it frames Lispector’s work purposefully without suffocating it; it manages to open up space for engaging with her work carefully, critically and freely — while still giving Lispector the last word.

(New Directions)

The world we experience through Lucrécia’s movements and her stream of consciousness is a different one: This world challenges the supremacy of reason and the common notion that the mind reigns over the body – something that can be broadly defined as the Cartesian mind/body split. By carefully centering touch and the body, Lispector’s language and writing style keep challenging those ways of thinking that still follow from this split — a challenge which was also the reason why she was such an inspiration to the French feminist writer and theorist Hélène Cixous. Similar to her other works, like Agua Viva or The Hour of the Star, The Besieged City remakes language in such a way that the text cannot simply be enjoyed with the mind, but needs to be sensed and imagined by the body — troubling our separation of the two.

The book also moves beautifully between Lispector’s play on the notion of seeing and her sharp and unapologetic critique of patriarchy and gender norms: “[B]ut whatever a man sees is a reality. And without realizing it the girl took the shape that the man had perceived in her. That’s how things were built.”

With this new translation, it once again becomes clear that having more of Lispector in English means we have more to discuss in relation to subjectivity, gender, language and materiality. Reading The Besieged City is a dare to merge the material with the ideal. The way Lispector works with corporeality, and with matter and thought is not just worthy of travelling across cultures via an English translation; it is a much needed perspective for anyone who wishes to experience the world differently, to see it anew beyond the norms of reason.

Leave a Reply