There are still a few odd jottings and stray scribbles from the pen of Jack Kerouac – elusive bits and bobs published during the author’s lifetime – that remain unrecorded in bibliographies and/or uncollected in compilations of his writings. Admittedly, these fugitive fragments of Kerouac’s writing are not necessarily all lost literary gems, but I would argue that they merit the attention of readers seriously interested in Kerouac’s life and work.

One largely overseen category of stray compositions by Kerouac consists of the short contributor’s notes written by the author for the sundry periodicals and anthologies in which his work appeared. Kerouac’s biographical notes – each individually formulated by him for the particular publication printing his work – are unique compositions and interesting for their presentation of his life, his literary influences, as well as his attitudes and aims as seen by him at the time of writing. The autobiographical statement that accompanies the publication of “The Origins of Joy in Poetry” and two poems in Chicago Review, Spring 1958, is, perhaps, the most curious of all of the author’s autobiographical notes. The note outlines the usual information, date and place of birth, education, sports, early writings, experiences in the merchant marine, travels, but concludes with a disconcerting pronouncement: “… so now I can only say my motto is I DON’T KNOW I DON’T CARE AND IT DOESN’T MAKE ANY DIFFERENCE (my final philosophical statement).” 1 For those familiar with Kerouac’s writing up to and after this point, this bald assertion seems uncharacteristically despairing, even nihilistic.

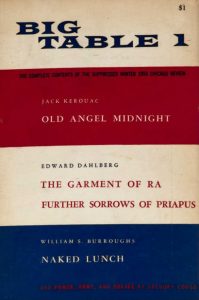

By way of contrast, in an autobiographical statement appearing in Big Table, No. 1, Spring 1959, Kerouac again lists his various occupations (railroad brakeman, seaman, etc.) but represents himself as a “student” of eight writers and two spiritual traditions. (The latter seeming to contradict the despondence and weary, fatalistic indifference implied in the Chicago Review note cited above.) The writers from whom he credits inspiration and instruction are William Blake, Arthur Rimbaud, Herman Melville, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson and James Joyce. This list differs significantly from the personal pantheon Kerouac enumerates one year later in his biographical note in The New American Poetry: Jack London, Ernest Hemingway, William Saroyan, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. 2 ]The spiritual traditions of which he states he is a student in the same Big Table note he names as being “the Tao and the Mahayana Aryan Buddhism of Gotama.” 3 Again, this is noteworthy, not only in opposition to the Chicago Review statement, but also since only a year later in the “Author’s Introduction” to Lonesome Traveller, Kerouac describes himself as a “strange solitary crazy Catholic mystic.” 4 Clearly, these were years in which the author underwent transformative psychological and spiritual experiences (see Big Sur) that altered him radically in terms of the beliefs he held.

By way of contrast, in an autobiographical statement appearing in Big Table, No. 1, Spring 1959, Kerouac again lists his various occupations (railroad brakeman, seaman, etc.) but represents himself as a “student” of eight writers and two spiritual traditions. (The latter seeming to contradict the despondence and weary, fatalistic indifference implied in the Chicago Review note cited above.) The writers from whom he credits inspiration and instruction are William Blake, Arthur Rimbaud, Herman Melville, Mark Twain, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson and James Joyce. This list differs significantly from the personal pantheon Kerouac enumerates one year later in his biographical note in The New American Poetry: Jack London, Ernest Hemingway, William Saroyan, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. 2 ]The spiritual traditions of which he states he is a student in the same Big Table note he names as being “the Tao and the Mahayana Aryan Buddhism of Gotama.” 3 Again, this is noteworthy, not only in opposition to the Chicago Review statement, but also since only a year later in the “Author’s Introduction” to Lonesome Traveller, Kerouac describes himself as a “strange solitary crazy Catholic mystic.” 4 Clearly, these were years in which the author underwent transformative psychological and spiritual experiences (see Big Sur) that altered him radically in terms of the beliefs he held.

A handful of unremarked, uncollected publications by Kerouac appear in the form of letters written to the editors of various magazines. The author’s aim in two of these letters is to correct what he sees as misapprehensions concerning the nature of the Beat Generation. A letter to the editor of Escapade magazine, titled “A Communication,” appears in the April, 1960 issue of that journal. Kerouac’s short message expresses his disapproval of the motion picture, “The Beat Generation,” which he views as a work of “insulting ugliness” for its preposterous and malicious characterization of harmless, bookish bohemians as psychotic criminals. 5

Similarly, a letter to the editor of Playboy magazine, printed in the March 1961 issue, is a response by Kerouac to a story written by Roger Price titled “Father Brother and the Cool Colony,” which appeared in the December 1960 issue of the magazine. To Kerouac, Price’s story was a further example of the phenomenon later named “beatsploitation,” that is the ignorant, commercial caricaturing of Beat figures, — a practice not uncommon in film, television and printed media during the time. In his letter, Kerouac states emphatically that no such entity as a “cool colony” exists, nor should it exist. The notion, he writes, is as ludicrous as that of a “square colony.” Kerouac deplores both Price’s attribution to the Beats of a sneering contempt for squares, and Price’s depiction of Beats as expressing superior scorn for certain occupations or professions. Such distinctions, Kerouac insists, were not made among the original Beats. What was, instead, seen by them as being of consequence in any individual was “the spirituality of the person.” 6

Similarly, a letter to the editor of Playboy magazine, printed in the March 1961 issue, is a response by Kerouac to a story written by Roger Price titled “Father Brother and the Cool Colony,” which appeared in the December 1960 issue of the magazine. To Kerouac, Price’s story was a further example of the phenomenon later named “beatsploitation,” that is the ignorant, commercial caricaturing of Beat figures, — a practice not uncommon in film, television and printed media during the time. In his letter, Kerouac states emphatically that no such entity as a “cool colony” exists, nor should it exist. The notion, he writes, is as ludicrous as that of a “square colony.” Kerouac deplores both Price’s attribution to the Beats of a sneering contempt for squares, and Price’s depiction of Beats as expressing superior scorn for certain occupations or professions. Such distinctions, Kerouac insists, were not made among the original Beats. What was, instead, seen by them as being of consequence in any individual was “the spirituality of the person.” 6

Both of these letters show Kerouac attempting to exercise some kind of restraining or directing influence over the concept of which he was the originator but over which he felt he was losing control to poseurs and opportunists.

In a similar manner, Kerouac is quoted by New York Journal-American columnist, Louis Sobol, as having written a letter or otherwise stated that he takes exception to being classified as a “beatnik,” and to being compared to Norman Mailer in terms of political views and ambitions. Kerouac is cited by Sobol as saying: “I am seriously devoted to my writing, and want to be considered a serious writer. I am a peace-loving citizen with nothing but love for my fellow men. I have no particular political leanings. It is not my fault that certain so-called Bohemian elements have found in my writings something to hang their peculiar Beatnik theories on. To repeat, I am a writer – author of some books that have found favour with readers – but I hope before I die, I’ll be recognized for what I really am – someone who never was and never cared to be of the Beatnik clan.” 7

On the basis of the letters described above, we may infer that Kerouac saw the integrity of his original vision of the Beat Generation as being threatened on two fronts. From one direction came the menace of facile, crass, commercial misappropriation of the Beat idea, while from another direction came the peril of aberrant encroachments upon the Beat spirit by self-identified followers. In this regard, another, as yet uncollected bit of writing from the author’s pen addresses in as definitive a manner as possible the topic of the Beat Generation. It is, in fact, a definition of the movement solicited from Kerouac by the editor of the American College Dictionary. As concisely and precisely as possible, Kerouac writes: “Beat Generation: Members of the generation that came of age after World War II, who espouse mystical detachment and relaxation of social and sexual tensions, supposedly as a result of disillusionment stemming from the cold war.” 8 This definition attempts to preclude the kind of sneering intellectual superiority misattributed to Beats as well as the fractious leftward political turn of some Beat writers that Kerouac feared would attenuate and ultimately displace the essentially spiritual character of the Beat Generation, as he conceived it.

A further uncollected letter to the editor of Escapade, printed in the June 1960 issue, is a defense by the author of an earlier article written by him on bullfighting that appeared in the December 1959 number of Escapade. Kerouac’s disapproving description of a bull fight he attended in Mexico had provoked among the magazine’s readership several aficionados of the sport who wrote to the editor mocking and deriding what they saw as Kerouac’s sentimentality. In his written response to the reaction generated by his piece on bullfighting, Kerouac gives no ground but reaffirms his sense of the essential cruelty of taunting, torturing and killing bulls for sport, stating emphatically: “I do not believe it is a grand thing for men to prove their goddam dignity at the expense of some dumb beast.” 9 Readers familiar with the author’s gentle ethos will recognize here a theme recurrent in Kerouac’s writing. Kerouac’s rare indignation is reserved for those who knowingly inflict harm on their fellow humans and creatures with whom they share life and sentience.

A further uncollected letter to the editor of Escapade, printed in the June 1960 issue, is a defense by the author of an earlier article written by him on bullfighting that appeared in the December 1959 number of Escapade. Kerouac’s disapproving description of a bull fight he attended in Mexico had provoked among the magazine’s readership several aficionados of the sport who wrote to the editor mocking and deriding what they saw as Kerouac’s sentimentality. In his written response to the reaction generated by his piece on bullfighting, Kerouac gives no ground but reaffirms his sense of the essential cruelty of taunting, torturing and killing bulls for sport, stating emphatically: “I do not believe it is a grand thing for men to prove their goddam dignity at the expense of some dumb beast.” 9 Readers familiar with the author’s gentle ethos will recognize here a theme recurrent in Kerouac’s writing. Kerouac’s rare indignation is reserved for those who knowingly inflict harm on their fellow humans and creatures with whom they share life and sentience.

On a more affirmative note, Kerouac writes to the editor of Metronome (No. 5, May 1961) praising the whole of the former issue of the (jazz-oriented) journal, and singling out for particular praise a piece written by Lenny Bruce. (This would have been “Lenny Bruce Cries Foul,” in the March 1961 issue of Metronome.) This latter letter – brief though it is – seems to me more characteristic of the author who was by nature far more inclined to be generous and inclusive, to praise and embrace, than to criticize and condemn.

A relatively obscure, still uncollected piece by Kerouac, entitled “Dave,” appears in the literary review, Kulchur, (No. 3, 1961). Preceding the piece, a note by Kerouac states that it was “Dictated to me in Mexico City 1952 by David Tercerero – died November 1954.” 10 Readers of William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac will recognize the figure of Dave Tercerero (actually Tesorero). He appears under the name of “Old Ike” in Burroughs’s novel, Junkie (1953), and is mentioned in Kerouac’s Tristessa 9 (1960) as “Dave,” former husband of Tristessa, already dead at the time of the novel’s narrative: “dead Dave my old buddy of previous years dead now” (p. 12) Tristessa keeps a photo of him on the wall of her tenement apartment. Interestingly, Dave Tercerero also appears as a player in Kerouac’s fantasy baseball game, playing both for the Thunderbirds and the Cincinnati Blacks. (See Kerouac at Bat: Fantasy Sports and the King of the Beats by Isaac Gewirtz, New York, 2009, p. 62, p. 66.)

A relatively obscure, still uncollected piece by Kerouac, entitled “Dave,” appears in the literary review, Kulchur, (No. 3, 1961). Preceding the piece, a note by Kerouac states that it was “Dictated to me in Mexico City 1952 by David Tercerero – died November 1954.” 10 Readers of William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac will recognize the figure of Dave Tercerero (actually Tesorero). He appears under the name of “Old Ike” in Burroughs’s novel, Junkie (1953), and is mentioned in Kerouac’s Tristessa 9 (1960) as “Dave,” former husband of Tristessa, already dead at the time of the novel’s narrative: “dead Dave my old buddy of previous years dead now” (p. 12) Tristessa keeps a photo of him on the wall of her tenement apartment. Interestingly, Dave Tercerero also appears as a player in Kerouac’s fantasy baseball game, playing both for the Thunderbirds and the Cincinnati Blacks. (See Kerouac at Bat: Fantasy Sports and the King of the Beats by Isaac Gewirtz, New York, 2009, p. 62, p. 66.)

“Dave” is a first person account of Dave Tercerero’s life from boyhood to young manhood. It is a tale of poverty, adversity, danger and struggle. The narrator recounts his misadventures from a peripheral participation in the Mexican Revolution to a career as a thief on both sides of the border, relating the circumstances of his incarcerations, escapes and morphine addiction. Beyond the intrinsic interest of the events themselves, the text is noteworthy as an example of Kerouac’s fascination and empathy with socially marginal figures. Readers will recall the author’s many sympathetic depictions of hoboes, ex-cons, junkies, prostitutes, eccentrics and outsiders. “Dave” is also significant as an illustration of Kerouac’s informal literary-aesthetic sensibility, his predilection for spontaneity and for an oral, candid quality in writing. Dave’s account of his life may lack eloquence, formal organization and grammatical correctness, but it possesses the authority of personal truth and a broader human pertinence.

A final fragment of forgotten, uncollected Kerouaciana is to be found among the pages of an academic journal called Twentieth Century Studies published by the University of Kent at Canterbury. This brief appearance in print, among the very last during the author’s life, consists of a 67-word reply made by Kerouac to a survey conducted by the journal among prominent authors on the topic of the sexual revolution and the depiction of sexuality in literature. A section of the magazine, under the title “The Professional Viewpoint,” was set aside to present the written statements the authors had made in response to the journal’s query.

Kerouac’s statement is personal and poetic. He declares that for his own part the sexual revolution began when he was sixteen. He describes a scene when he attempted to kiss his girlfriend through a wire screen door. In response, his girlfriend eagerly, vigorously threw open the door and engaged with him in a passionate kiss. Kerouac concludes his anecdote with the phrase: “And we sang Sanity beneath the trees.” 11

Kerouac’s anecdote celebrates the overcoming of artificial barriers (the screen door) to natural joy, and the momentary recovery of Edenic harmony. This sense of the essential innocence of sexual love is recurrent in Kerouac’s writing, though often tempered by an awareness of the destructive aspects of the sexual appetite. As if to affirm that an ideal romantic-erotic encounter (such as that depicted in the anecdote) may be experienced as a kind of sacrament, rather than a lapse or transgression, Kerouac ends his contribution to the forum on the sexual revolution with a closing salutation to the reader, a blessing: God be with you.

Scrutinizing these scattered scraps of the sprawling Kerouacian chronicle, we see an author engaged in defining and defending the vision that animates his writing, a vision of the mad, melancholy, heroic and holy nature of human life. While they are not neglected masterpieces awaiting rediscovery, these uncollected minor pieces make up a varied and vivid lot that serve to extend and deepen our knowledge of Jack Kerouac’s continual evolution and abiding concerns as a writer.

NOTES

1. “Notes on Contributors,” Chicago Review, Vol. 12, no. 1, Spring 1958, p. 108.

2. “Biographical Note” by Jack Kerouac, The New American Poetry 1945 – 1960, edited by Donald M. Allen (New York: 1960) pp. 438-39.

3. “Notes on Contributors” by Jack Kerouac, Big Table, No. 1, Spring 1959, p. 2.

4. “Author’s Introduction” by Jack Kerouac, Lonesome Traveler (New York: 1960) vi.

5. “Barbs and Balm,” Escapade, Vol. IV, No. 3, April 1960, p. 66.

6. “Dear Playboy” letter from Jack Kerouac, Playboy, Vol. 8, No. 3, March 1961, p. 5.

7. “Kerouac Protests Legend” by Louis Sobol, New York Journal-American, Thursday, December 8, 1960.

8. The American College Dictionary, Clarence L. Barnhart, editor-in-chief, (New York: 1962).

9. “Barbs and Balm,” Escapade, Vol. V, No. 4, June 1960, p. 68.

10. Kulchur, No. 3, January 1961, pp. 3 – 5.

11. “The Professional Viewpoint,” response by Jack Kerouac, Twentieth Century Studies, Vol. 1, March 1969, p. 118.

Paul Maher Jr. says

Wonderful piece of research. Thank you!

Gregory Stephenson says

Thank you so much, Paul! I’m a major admirer of your writing, so I’m all the more pleased.