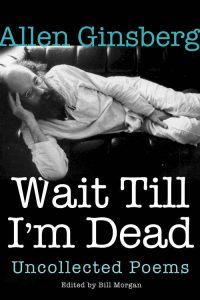

Wait Till I’m Dead: Uncollected Poems by Allen Ginsberg (Bill Morgan, ed.) / Grove Press / hardcover

When I first heard about this book of uncollected poems by Allen Ginsberg, I imagined a slim volume of “b-sides” that would be “for the completist” as my cinephile friend describes the lesser, flawed films of his favorite directors.

To my surprise, it was more interesting and many more pages than that. Bill Morgan has really tracked down over a hundred Ginsberg poems that “would have gotten away.” He has also arranged them according to decade, which is extremely helpful in examining their context. Poet Rachel Zucker writes the intro, and though I’m not sure why she was chosen, it is still a good opening:

“When I first read Allen Ginsberg’s poems as a teenager, they worked on me like a gateway drug.”

How many readers of this review now nod their heads in agreement?

Ginsberg rhymed in the 40s, and the poems of this decade are certainly promising, but “Behold! The Swinging Swan” is a missing stanza from what would become “Pull My Daisy”, written with Jack Keroauc:

Say my oops

Beat my bones

All my eggs are scrambled.

Someone with a passing knowledge of Ginsberg’s oeuvre generally considers the 50s “Howl” Allen’s best poem, and if the reader has delved further, this may have been replaced with “Kaddish” (Allen felt the latter).

The 50s were the explosion that we know as Allen Ginsberg, and here we find a smaller poem, “Dawn,” which, though post-“Howl,” is more in keeping with the straight objectiivsm of his book pre-“Howl” writings in Empty Mirror, a directly William Carlos Williams-influenced collection:

live/in the physical world/moment to moment

Also, there is “On Nixon: Chain Poem,” written with Kerouac and Gregory Corso:

Nixon’s eyes whip back and forth like taxi cabs

The favorite Ginsberg persona, echoed even on the cover of this book, is his immediate post-India one, dressed in white Hindu-like pajamas, hair and beard at their wildest. Still, those who relate to this persona (where Allen began his most gregarious media expression) may be hard-pressed to name a favorite poem from this 60s Vietnam-era period. Certainly they are there – “Wichita Vortex Sutra” and “Wales Visitation” among them. I knew “New York to San Fran” from the small press volume Airplane Dreams, but didn’t realize it had never made it into Ginsberg’s Collected Poems:

Everybody forgets who’s body/ suffers the physical pain or Orders/ undreamt in these High Air/ Conditioned modern Powers.

It is not unusual for the casual reader to find little of interest beyond that, though it is most often “contempt prior to investigation,” as Herbert Spencer put it. The 70s, as clearly indicated in this collection, show a shift from his psychedelic syntax to the more direct objectivism of his old mentor William Carlos Williams – simple journalistic image that most can understand, perhaps even 100 years from when they were written. This is also the profound influence of Allen’s Tibetan Buddhist teacher, Chogyam Trungpa. The objectivism is coupled with a haiku-like appreciation without grasping, which also echoes Jack Keroauc’s haiku and sketches from his own discovery of Buddhism in the mid-50s. The poems and attention are much smaller, quieter, and more easily overlooked. From this decade, “Verses Included in Howl Reading Boston City Hall” is a new treat:

It is not unusual for the casual reader to find little of interest beyond that, though it is most often “contempt prior to investigation,” as Herbert Spencer put it. The 70s, as clearly indicated in this collection, show a shift from his psychedelic syntax to the more direct objectivism of his old mentor William Carlos Williams – simple journalistic image that most can understand, perhaps even 100 years from when they were written. This is also the profound influence of Allen’s Tibetan Buddhist teacher, Chogyam Trungpa. The objectivism is coupled with a haiku-like appreciation without grasping, which also echoes Jack Keroauc’s haiku and sketches from his own discovery of Buddhism in the mid-50s. The poems and attention are much smaller, quieter, and more easily overlooked. From this decade, “Verses Included in Howl Reading Boston City Hall” is a new treat:

…who were busted for eye-contact in the Boston Public/ Library men’s room/when a handsome youthful policeman flashed his Irish/ loins & winning smile over urinal, & then exhibited his badge

Also, “A Brief Praise of Anne’s Affairs,” gossiping about Anne Waldman, with whom he had now founded the Jack Keroauc School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa (then) Institute:

She has affairs with Poets & Poetesses,

Novelists, Bards & Carpenters

She has affairs with international

Shamanic minstrels dancing naked

She has affairs with herself on the side

like everybody else

For myself, I immediately turned to the 80s first, because this was Allen as a mature student of Buddhism, professorial in trimmed beard, suit and tie, which I feel to be the culmination of his search and arrival as a poet and mystic. This is where examing Ginsberg as just a poet becomes complicated, because how he examines current events and his own incipient old age and death take on a larger, philosophical element (much like his impact on socio-political issues) that is more than what is on the page. In terms of ‘big poems”, “Contest of Bards,” already published in the 80s in Mind Breaths, has a Prospero-like Shakespearean summation of where he was at that I find particularly pithy in its self-deprecation.

From this period, we now have “Trungpa Lecture,” which I’d originally read…er…somewhere or other (and not where it was first printed, showing the value of the collection here):

…Holding my cock to pee, the Atlantic rushes out. Sitting down to eat, Sun and Moon fill the plate.

The 90s are sparse in this book, but what is there (particularly “Last Conversation with Carl Solomon or In Memoriam”) is certainly worthy of attention:

Carl: Death is fading away – /which I’d like to go easily/like my mother…imitate/ my mother…

Also, “Dream of Carl Solomon”:

I meet Carl Solomon/”What’s it like in the afterworld?”/”It’s just like in the mental hospital./You get along if you follow the rules.”

Lastly, “[Poem]'”:

The moon in the dewdrop is the real moon

The moon in the sky’s an illusion

Which Madhyamaka school does that represent?

What we come away with is wanting more, and wishing we knew what Allen would say about these complicated times. His Buddhist name translated was Dharma Lion Peace Heart. I miss his lion’s roar and purr.

Leave a Reply