Calling on Paul Bowles

Tangier, Morocco, August 1979

”There it is,” someone says, and in the darkness, in the distance, you can see Tangier sprawled across several hills, a white city illuminated by electric lights and veiled by a thin fog.

After docking, disembarking and a wearisome wait to clear Moroccan customs, we take a taxi to our hotel, hurtling through the midnight streets of Tangier past Ramadan revelers and bright cafés. At the hotel, a desk clerk denies all knowledge or record of our reservation until Birgit produces from her purse a letter of confirmation. We are shown to a room and soon fall into an exhausted sleep. (The previous night at a hotel in Malaga we had been kept awake until 4.30 a.m. by a raucous party taking place in the room next door to ours, and were then awoken at 7 a.m. by a phone call from a furious desk clerk berating us for having caused the commotion and ordering us out of the hotel immediately. He wouldn’t stop yelling long enough for me to assert our innocence.)

I wake in the dark, hauled up from deep strata of sleep. In the street below a dog is barking. The bark is deep, resonant and insistent, the bark of a big dog and very near. On and on he barks. Long minutes pass. I despair of sleep. Then, from the street there is the sharp report of a firearm being discharged. A single loud shot, then silence. “My God,” I think, “this really is a tough town.” Hours later I wake to the muezzin’s call to prayer.

We spend the day wandering in the medina, or old city. In the evening we walk to the Inmeuble Itesa, an anonymous concrete building on the outskirts of Tangier where Paul Bowles lives. We ascend to the fourth floor, ring the bell and are admitted by Bowles who greets us by name. We are expected and welcome, he says.

A few years before our visit we had written to Paul Bowles, soliciting a contribution to our literary journal, Pearl. He kindly obliged by sending us a poem. An exchange of letters ensued in the course of which he extended to us an invitation to call upon him in Tangier. When (after about 18 months) we accepted, he provided us with his street address which is not the same as his postal address.

We enter and shake hands and are offered tea. Black tea with slices of lemon, served in cups of thick transparent glass. Bowles’ modest but modern apartment consists of three or four rooms. There is a hallway stacked with old suitcases, a small kitchen, and a dim bedroom with an adjoining bathroom. The living room is furnished with low wooden tables, colored cushions for sitting and a low couch. There is a fireplace, a shelf of books and a large studded wooden chest. The floors are covered with red, black and tan Moroccan rugs. Leaning against the walls are framed paintings by Ahmed Yacoubi and Mohammed Mrabet. On the mantel and the tables are placed objects of hammered brass and an antique long-stemmed, small-bowled, silver oriental water pipe. Outside, but visible from the living room, there is a balcony crowded with tall plants.

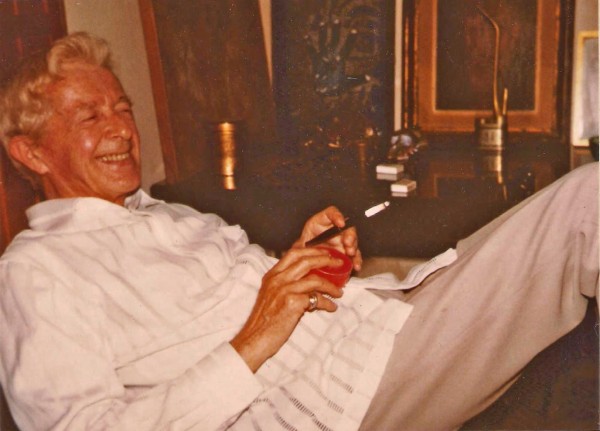

Bowles is a slender man with blue eyes and thick white hair. He is dressed with casual elegance in well-fitting clothes, a white Moroccan-style shirt and tan slacks. On the little finger of his right hand, he wears two gold rings. He chain smokes kif cigarettes from a black cigarette holder.

We have brought with us from Denmark gifts for Bowles: two black leather notebooks, a stoneware bottle of Danish mead and a pound of black tea steeped in the juice of blackcurrants. He receives these graciously, inspects them carefully and pronounces himself eager to try the tea whose fragrance he inhales with obvious interest and approval. He asks us our impressions of Tangier so far. We are both ardent in our praise of the city, especially the medina. We’ve never seen anything comparable. Bowles smiles and seems pleased by our naive enthusiasm. “You weren’t annoyed by the touts?” he asks with concern. We assure him that we were courteously firm with them and did not find them bothersome. Again, he seems pleased, even relieved, as if he considers himself responsible for our having a good time in Tangier or as if he is anxious that his city (as it were) might arouse aversion in some visitors.

Bowles offers us kif cigarettes which we accept and he then discourses on kif, saying that it should be bought fresh and that ideally one should prepare ones own kif, chopping the dried cannabis leaves into a fine powder and mixing the powder with an appropriate amount of tobacco in order to achieve a congenial blend. Some professional cutters of kif are highly skilled, others less so. Accordingly, their product varies in quality. The hashish available in Tangier is of very poor quality, he says, consisting of the leftover leaves of the cannabis plant after the small potent kif leaves have been carefully removed. Bowles forms kif cigarettes for his own use by emptying the tobacco from a Marlboro and then filling the paper cylinder with the fresh mountain-grown kif he has recently purchased in the marketplace from wonted and reliable vendors. He stores the kif intended for his immediate use in a small round red container which he keeps close at hand.

Madame Claude Nathalie Thomas arrives and speaks with Bowles concerning her translation of certain of his short stories. Mohamed Choukri (whose book A Life Full of Holes was dictated to and translated by Paul Bowles) comes to call. A dark-haired, sad-eyed man, he engages Bowles in a conversation in Spanish. Then, soon after Choukri’s arrival, Mohammed Mrabet makes his entrance, immediately compelling attention by his energy, his intensity and an aura of danger that he projects. Directly, he seizes the conversation (speaking Spanish, ignoring Choukri) and thereafter keeps it in his possession.

Mrabet is a handsome, agile, mobile, muscular man about 40 years of age. He is dressed in faded blue jeans and a bright orange short-sleeved shirt with vivid paisley trimmings. With his heavy finger rings and his large silver wrist watch, there is about him something of the air of a brigand or Barbary pirate, flashy and fierce. Birgit and I know and admire his writing and have brought some gifts for him, but I’m embarrassed to give them to him in the presence of Mohamed Choukri, so I wait for an opportunity to take him aside.

At length, as Mrabet seems to be leaving, I succeed in speaking to him alone and off to one side. I know that he does not speak English and since I don’t speak Spanish I address him in French. I tell him that we esteem his books and I present him with the gifts we’ve brought: an ornate Spanish pocket knife, a jar of dark Danish heather honey, and a pound of the same black tea flavored with blackcurrant that we’ve brought for Bowles. Mrabet is touched and pleased with the gifts. He thanks us and promises that he will soon return. He must first make a quick visit to his mother.

Mohamed Choukri leaves and Madame Thomas also leaves. Bowles plays tapes of Moroccan music and percussive, oriental-sounding music by an American composer named Lou Harrison. We smoke kif and drink tea and Bowles eats a late dinner of soup, rice and chicken. He tells us that he eats only two meals a day, breakfast and dinner. He gets dizzy sometimes, he says, adding with a smile that it may be that the kif he smokes all day contributes to this condition. I ask him if he has kept up with developments in jazz since his days as a music critic in New York. No, he replies, his knowledge of jazz effectively ends in the mid 1940s before the advent of bebop. He still respects Duke Ellington as a composer and a conductor. He found Ellington’s musical ideas very inventive, his band expressive and exciting. Other individual musicians whose work he admired during the 1940s included Fats Waller, the pianist Albert Ammons, the guitarist Charlie Christian, the alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges, as well as the pianists James P. Johnson and Teddy Wilson. But since moving to Morocco he has, of course, been unable to attend live performances while access to current recordings is difficult and expensive.

Mrabet returns with a delicious Ramadan desert made by his mother which we enjoy with fresh tea and more kif. When Mrabet has smoked a sufficient amount of kif he begins to recount personal anecdotes, one after another. For our sake, these are related by him in French. The majority of his narratives on this occasion consist of angry stories involving betrayal and revenge. As he speaks, he is animated, passionate, the veins standing out on his neck. He believes he has been poisoned by his former wife. He believes that she tricked him into eating finely ground glass mixed into his food. Only recently his stomach has been operated on and while he was in the hospital his wife destroyed all his belongings, killing his pets and even his plants. But again and again he insists “Je suis content.” (I’m happy.) He claims that he has accepted and transcended his sufferings. He believes that one should return good for evil, the more evil done against one, the more good must be done in return, a ratio of ten to one. Mrabet also recounts how one of his brothers killed his wife, spent 13 years in prison, then upon release engaged in further crimes and knifings until at last he was killed. Life is full of suffering, he says. He has himself suffered much, but then he adds “Je suis content.”

As we make to leave, thanking our host, we ask him to sign our copy of Let It Come Down, an English first edition of the book. Bowles studies the dust wrapper with interest and seems somehow impressed that we have with us this particular copy. Why don’t we return for it tomorrow? he suggests. We are welcome to call on him every evening during our stay in Tangier, he says. We are surprised and deeply pleased, having thought that his invitation to visit him was for a single call, a single evening. (When the next evening Bowles returns the book to us, signed and inscribed, he asks us humbly if we enjoyed the novel. Oh yes, yes, very much, we tell him and he beams with pleasure.) Mrabet drives us to our hotel. En route he tells us of his deep affection for Bowles and that if Bowles should die it will mean the end of Mrabet as a writer, since it is Bowles who translates his stories into English. And he has an ominous feeling concerning the present state of Bowles’ health; he fears Bowles may be sick. In any event, Mrabet estimates that they may have only two productive years of work together remaining.

Fascinated by the medina, we return there again and again during our days in Tangier. The white flat-roofed buildings, the steep narrow streets in sharp light and shadow, the shops, stalls, small cafés, the souks and bazaars, the men in hooded brown djellabas, the veiled Arab women in black robes, blue robes and white robes, the Berber women with their wide-brimmed, high-crowned straw hats, their shawls, their red and white striped skirts, the pavements of cobble stone and brick, the windows with their pointed arches, the white-washed walls, the wooden doors, the blue shutters, the wrought iron balconies and grilles, the stairways and dark alleys, the awnings and tiled doorways, the arched passageways and impasses, the shoe-shine boys and beggars, the vendors of lottery tickets, the peddlers, the water seller in his tasseled straw hat with his brass cups and goat skin water bag, the shuffling slippers and sandals in the winding streets. The children’s’ shoes arranged outside a small Koranic school, the cross-legged tailors, the carpenters hammering and sawing in their narrow shops, the candies, cashews and almonds piled in heaps, the ceramics, brass and copper, the leather goods, the melons, the metal and plastic buckets filled with Barbary figs, the spices, cloth, fresh meat, onions, goat cheese, the fruits and vegetables and eggs. The odor of rat poison in the Kasbah. The taste of sweet mint tea at the Café Centrale. And lying at intervals here and there, face up in the dusty streets — like a fortune teller’s scattered spread – castaway Baraja playing cards with their strange tarot-like suits and symbols.

Bowles picks us up at our hotel in his gold 1965 Ford Mustang, driven by his chauffeur, Abdelouahid Boulaich, a trim, balding man. Bowles and Abdelouahid converse in Spanish. We are driven west along a winding road, out of the city, up into the mountains, past luxurious villas and into a forest of eucalyptus, pine, cypress and jacaranda. We follow a dirt road through the forest, park the car and walk to a large lichen-splattered rock perched above the sea. The breeze is fresh and fragrant. The air is vibrant with the whine of cicadas. “This is my favorite spot,” Bowles says. Below us in the distance we can see goats grazing the slopes and children fishing in the sea. We walk paths thick with pine needles and approach the Villa Perdicaris whose owner Ion Perdicaris, together with his son-in-law, was kidnapped and held for ransom by the Berber bandit Mulai Ahmeder Raisuli in 1904. This incident proved to have repercussions far beyond Morocco as Perdicaris was at first believed to be an American citizen. President Theodore Roosevelt dispatched a fleet of warships to the coast of Morocco, pressuring the Sultan and demanding “Perdicaris alive or Raisuli dead.” Raisuli’s demands were met by the Sultan, Perdicaris and his son-in-law freed, while Raisuli went on to become Pasha of Tangier and governor of Jibala province. Bowles smiles as he tells us that a recent Hollywood film (“The Wind and the Lion” starring Sean Connery and Candace Bergen) treating the Perdicaris incident has been made in which the victim of the bandit’s kidnapping is a woman while the bandit Raisuli is portrayed as a noble rebel fighting tyrannous oppression. Bowles has not seen the film, he says, but he has read of it. The Villa Perdicaris itself is a large Gothic sort of house with crenellated towers. It is abandoned and in a condition of disrepair. We drive to Cape Spartel where the waters of the Mediterranean meet those of the Atlantic Ocean. Palm, broom, cork-oak and eucalyptus abound here. A solitary lighthouse is situated on a promontory overlooking the vast Atlantic. During our journey together, I note that Bowles (once a noted composer) frequently whistles elusive musical passages or taps out rhythms on the dashboard or with his arm out the window on the roof of the car. Are these habits, I wonder, outward expressions of rhythms and harmonies he might be hearing in the privacy of his mind, tokens of a sort of interior musical monologue? I recall reading a comment by Ned Rorem who – regretting the fact that Bowles had abandoned his work as a composer – pronounced a hope that “Someday Bowles may release the underestimated musician who doubtless still sings within him.”

That evening in Bowles’ kitchen, Mrabet prepares for us a Moroccan tagine, a delicious stew of chicken, onions, olives and mushrooms, served with a wonderful brown bread baked by Mrabet’s mother. In respect for Ramadan, we wait until the sunset cannon has been fired, then we eat seated on the floor around the living room and even Bowles eats heartily. Bowles plays tapes of Moroccan music that he has recorded just outside his window. After dinner, kif is smoked and Mrabet tells numerous stories. These include the tale of a queen and a golden chain, the story of a baker who found a diamond, and the story of a poem that came to Mrabet while he was in jail: “Breast on breast/With your hair disheveled/ Bought a ring/worth two ships/My gazelle/The ships have sailed.”

At Bowles’ suggestion, Mrabet also relates to us the story of how he discovered a magic bundle hidden in the soil of a potted plant in Jane Bowles’ apartment. (Birgit and I have already read somewhere of this incident but are fascinated to hear it related by the principals.) One night Mrabet had dreamed of the presence of something evil in one of the potted plants in Jane Bowles’ house in the medina. The following day he deliberately visited the house and attempted to examine the plant, but he was attacked by Cherifa, Jane Bowles’ Berber housekeeper, who drove him away with blows and curses. This behavior on the part of Cherifa confirmed Mrabet’s suspicion that some form of black magic was being perpetrated on Jane by Cherifa. With the help of Paul Bowles, Mrabet succeeded in removing the plant, a stunted philodendron, to Bowles’ apartment. There, Mrabet examined the plant, finding a cloth packet buried among its roots, a packet composed of black magical ingredients intended by Cherifa to exercise a spell over Jane Bowles. This was not the first instance of Cherifa having planted about the house black magic packets. Mrabet considered her a witch and believed her responsible for Jane Bowles’ illness, both through magic and poisoning. Birgit and I are shown the very same philodendron plant on Bowles’ balcony, now large and thriving.

Bowles adds that this was neither the first time, nor the last, that Mrabet had dreamed true regarding Jane. On one occasion, he says, Mrabet had dreamed that Jane have given him a gold coin on a chain, and not long afterward such a gift had, indeed, been given to Mrabet by Jane. On another occasion, Mrabet had related to him a dream in which Mrabet had seen Jane Bowles holding a flower. There was something ominous and disagreeable about the flower, Mrabet had said. Mrabet was convinced that the dream portended some impending disaster that would befall Jane. Soon thereafter Bowles had received an urgent telegram from the clinic in Malaga where Jane was being treated. He was informed that her condition had worsened and had become critical. He traveled there with all haste, only barely reaching her side before she died. In this case, too, Mrabet’s unconscious intuition had proved to be accurate.

Again, by pre-arrangement, Bowles calls for us at our hotel and we are driven in his Ford Mustang by Abdelouahid Boulaich, traveling east out of Tangier. The goal of our excursion is to be shown Abdelouahid’s house, a house which he has been constructing by himself and which is now sufficiently compete for both him and his wife to occupy. The terrain is arid and hilly, rock-strewn and brown. Cattle and goats graze on shrubs. There are prickly pear cacti and agave plants. Many of the latter have bloomed and are now dead as signaled by their tall, dry stalks. Overhead, in the blue air, a buzzard hovers, slowly circling. We pass Berber countrywomen in their broad straw hats, leading laden donkeys. Cattle are driven along the road by boys with sticks. In a field, a flock of camels stands and reclines. The afternoon is bright and silent. The only sounds are the whine of cicadas, the baaing of goats, the crowing of cocks. Along a tree-lined road, farmers, their dogs and donkeys are resting in the shade.

Bowles points out to us the tomb of Sidi Ali, purple, gray massive Jebel Musa (the southern pillar of Hercules) and the ruined Portugese fort at Ksar es Seghir. We follow narrow dirt roads to the hillside house of Abdelouahid. The exterior of the house is white, the flat roof is crenellated to resemble a fortress. There are wrought iron grilles on the windows. The interior is cool but we stand and sit outside on a walled porch paved with flagstones. Abdelouahid serves us mint tea and fresh figs, but after a few wary sips Bowles remarks that the tea tastes strange. He believes that standing water must have been used to make the tea. He consults with Abdelouahid in Spanish and the tea is removed. After an interval, Abdelouahid returns with a new pot of mint tea made with fresh water and Bowles pronounces it “perfecto.”

From our vantage on the hillside we can see the brown coast of Spain across the Strait of Gibraltar. I mention the memorial in Algeciras commemorating the landing there of General Franco and his army in 1936. Bowles recounts how Franco brought with him to Spain many thousand Moroccan troops, both conscripts and volunteers. Those Moroccans who joined usually did so to escape desperate poverty. “Los Moros” (the Moors) as the Spanish called the Moroccan troops inspired terror among the Spaniards. Their method of fighting, he says, was merciless, involving the indiscriminate killing of civilians. This practice was deliberately exploited by Franco as a means to subdue the Spanish population. In consequence, there is still a lingering ill-will toward Moroccans on the part of many Spaniards.

I tell Bowles that Birgit and I have over the years assembled our collection of his works (many of them out-of-print) by scouring used book shops around Europe, acquiring some of his books in unlikely circumstances. He recalls with fondness the stalls of the bouquinistes along the Seine where he found many curious and unusual books as well as back issues of the handsomely produced surrealist magazine, Minotaure, and other avant-garde literary journals. Indeed, it was in a similar manner, he says, that he garnered his early collection of jazz and blues records, finding them in secondhand furniture stores.

We talk of the remarkable art work done by untutored Moroccan painters such as Ahmed Yacoubi and Mohamed Hamri, both of whom early in their careers had been encouraged by Bowles. I mention that one of Hamri’s paintings is featured on the dust jacket of the English edition of Brion Gysin’s novel, The Process. “Ah yes, The Process,” Bowles says with a faint smile, suggesting that he esteems that book very little. Hamri, he relates, had earned his living as a smuggler and a house painter before ever applying paint to canvas. Unfortunately though not surprisingly, he says, Hamri had stolen a number of personal possessions from Gysin and from Bowles, too, though both men had befriended and encouraged him in his career as an artist, even providing him with art supplies. Bowles observes that Moroccans view foreigners as quarry, as a resource to be turned to economic account or utilized for some other advantage. This fundamental attitude on their part, he says, has been inherited by them from the time of the Barbary pirates.

In making such a pronouncement upon the behavior of Moroccans, Bowles evinces neither animus nor contempt, but rather an attitude of resignation to the inevitable. His perspective on humanity – its customs and behaviors – resembles that of a kind of ethnographer or anthropologist. He observes, remains objective, withholds moral judgment. He is intrigued by human passion and vanity, bemused without being condescending. His characteristic physical posture, that of a relaxed yet attentive poise also suggests this view of things. A common denominator underlying many of his remarks (concerning the decline of Tangier, the decline of Europe and the United States, the decline of travel, the decline of the quality of food, for example) is that we should be under no illusion concerning the character of the era we live in and the world we inhabit; we ought to have a clear, unblinking look at existence and phenomena but we must also accept that the state of things is irremediable.

We return to Tangier along the winding coast road. Distant misty mountains to the south. Blue sea breaking white on beaches to the north. Above us, an immensity of empty sky. Even on this short trip, scanning the landscape from the front seat of his chauffeur-driven car, Bowles seems in his element, intent, alert, the consummate traveler.

We’re taking a late-afternoon nap in our hotel room when the phone rings. It’s the desk clerk. “Mrabet est ici,” he says. (Mrabet is here.) I descend the stairs to the lobby, shake hands with Mrabet and ask him to come up to our room. He invites us to his mother’s house for dinner, to eat the fish that he has caught this afternoon at Ksar es Seghir.

Arriving at the house, we are introduced to Mrabet’s mother who in courteous Moroccan fashion after shaking our hands touches her open hand to her heart. We are served sweet mint tea and then share kif cigarettes with Mrabet (hand rolled by him using two Job papers) while listening to audio cassettes of chleuh music – pipes, string instruments, flutes, drums, singing. Mrabet tells us that kif smokers prefer chleuh music, jilala music or gnaua music. There was a time, he says, when particular forms of music caused him to enter a trance state, even against his will. Hearing such music he could not resist being drawn into a condition of unconsciousness while his body remained awake and active. While in this state, which might last for hours, he often injured himself. He has since trained himself to resist the music, he says, but he is still susceptible to the odor of bakhour, an incense. In spite of his best efforts to withstand its influence, the smell of bakhour will induce in him a trance state.

The three of us sit on the floor around a low round table and eat from a large common dish, using Mrabet’s mother’s excellent bread to maneuver our food. The first course is sheep liver in a spiced sauce. This is followed by Mrabet’s fish, a large sea bass, then flan for desert. After this delicious dinner, further kif cigarettes elicit from Mrabet a stream of stories. “I always tell stories at this time of night,” he says. He adds that when he is not smoking kif he becomes quiet and fat-faced. Once, he tells us, he abstained for the length of a year from smoking kif. He became nearly unrecognizable to his friends and even to his family. At last he accepted a pipe of kif from a friend and his friend looked with amazement at the sudden transformation of Mrabet’s face, exclaiming: “Ah, that’s the real Mrabet!”

One of Mrabet’s stories this evening concerns Birgit. She ate a loaf of bread as big as the sky then to quench her thirst drank seven rivers. Mrabet went to the market and bought a pomegranate that weighed five kilos but in attempting to bear it to his house he fell under the weight of it. The pomegranate broke in two. One of the halves had a door which he opened and entered, finding there a palace. Exploring the palace, he discovered a room full of honey. There he killed a large mosquito and filled its headless body with honey. He then flung the honey-filled mosquito across his shoulder, carrying it like a sack. However, attempting to cross a river, he accidentally dropped his burden, thereby sweetening the water. Exiting from the door he had entered in the broken pomegranate, he now noticed a door in the other half. He opened the door, entered, “and there you were, Birgit!” Ending his tale in this fashion, Mrabet laughs his customary curious and disconcerting laugh.

Mrabet’s strange laugh begins as a flash of teeth and eyes, followed by a rattle in the throat, a wheezing of the lungs. Then his eyes close and his face assumes an agonized grimace, the corners of his open mouth turned down like a mask of tragedy as he sobs with mirth. Even his saddest stories conclude with this laugh as if they are a sort of joke on the listener or as if life is a kind of joke on the living.

Mrabet sets great store by dreams. He is impressed when Birgit tells him that she dreamed that he visited us. “Tu as un bon coeur,” he tells her. (You have a good heart.) He makes her a gift of a silver chain with a silver coin on which there is a likeness of King Mohammed V. He loved Mohammed V, he tells us, truly loved him, and he suspects his son, the current king, Hassan II, of having had a hand in his sudden death. Accordingly, he has neither love nor respect for Hassan and feels himself estranged from the king and his entire administration. Mrabet has himself had an alarming dream, only last night. He dreamed that while combing his hair things began falling from his scalp, including three lice. He is convinced that this dream bodes ill for him and the prospect of impending misfortune troubles his thoughts.

Mrabet drives us to his café. The walls of the café are decorated with his paintings and drawings. Moroccan men sit at tables, drinking coffee, coca cola and glasses of mint tea, smoking, playing cards and parcheesi. On the television screen there is a religious discussion among bearded imams.

A strangely subdued Mrabet calls for us at our hotel. The intrigues and betrayals of his wife still weigh heavily upon him, he explains. Moreover, last night there was an incident in his café. An aggressive drunk came in and began at once to create a disturbance. Ultimately, the man knocked down Mrabet’s crippled waiter who then phoned Mrabet. Mrabet arrived and duly punched out the drunk. But the police intervened and took both of them to the police station where Mrabet had remained for long hours. Today, his right hand is swollen and sore. I note that he has moved his rings to the fingers of his left hand.

Mrabet wants us to see the town of Asilah. We drive south and west out of Tangier, bouncing along dirt roads in Mrabet’s dusty, battered, brown Ford Fairlane, a Bob Marley cassette playing. He tells us that he has nearly completed a new book to be titled Night Honey. It is the story of his terrible marriage and the sufferings that followed. “If you have a heart, you’ll weep when you read it,” he says.

Mrabet prides himself on his self-sufficiency, his independence. He can provide for all his wants and needs, he says. He traps birds to sell, he fishes, he hunts, he slaughters his own livestock, butchers his own meat, cooks his own meals. He is also fiercely proud that his family is from the Rif. He likes to be called “El Rifi” and often uses this name for autobiographical alter-ego figures in his novels and tales. The people from the Rif are the best people, he says, the cleanest and strongest, the most upright and pious, and the kif plants grown in the mountains there make the best kif.

Fierce light and the shrill, relentless whine of cicadas. Corn fields, rows of prickly pear, the tower of a distant mosque. The road suddenly crowded with cattle. And along the roadside, sheep, camels, goats, donkeys. Through a village, Had e Rabiah, and then to our right the blue sea under a wide blue sky. Railroad tracks, a sulfurous stench and then we are in Asilah. We walk the medina, the ramparts, view a crumbling Portugese fort, the tomb of Sidi Mansour. In the market, melons, peppers, tomatoes, squash, cactus figs, fish, crabs, hens. A ragged, turbaned, white-bearded old man sits on the ground with strange desert refuse displayed before him on a blanket. An old revolver dissolving in rust, broken dirt-clogged clay pipe bowls, tarnished brass cartridge cases. Fascinated by the man and his desert debris, I purchase some of his wares, counting dirham coins into his palm.

On the return trip to Tangier, Mrabet tells us that he makes daily calls on Paul Bowles. Indeed, he sometimes visits him as many as six times in a day. If you are friends then it should be that way, he says. You should see your friend every day even if only for a few minutes. He tells us that sometimes he may be engaged in repairing something or driving his car when suddenly he feels he should go to see Bowles. At such moments he fears that something may have happened to him. Sometimes, Mrabet says, he cleans Bowles’ apartment when the maid fails to appear. Some days she has to visit her son in jail and, of course, Bowles has no telephone.

In our hotel room we smoke kif cigarettes with Mrabet and view his photo album. There are photographs of Mrabet on the beach, young and muscular. There are photographs of relatives and childhood friends, his benefactors Russ and Anne-Marie Reeves, and his friends Paul and Jane Bowles. He was very fond of Jane Bowles, he tells us. He felt very close to her and her illness and death saddened him deeply. Mrabet repeatedly remarks that he feels he is now only a shadow of his former self, the younger Mrabet depicted in the photographs. Bad living (he used to drink alcohol) and misfortunes have weakened him. “I swear to you, I had fantastic strength;” he says ruefully, “if I had met Hercules I could have made salade nicoise of him.”

Then, Mrabet is off to the market to do his shopping: “a donkey’s ear, cloud butter, powdered water and a frog’s gallbladder.” He laughs in gasps while his face shapes a mask of tragedy.

Evenings in Bowles’ apartment unfold according to an implicit, organic pattern. There is black tea and kif, conversation, oral tales spontaneously composed by Mrabet. Late in the evening, cold melon is served. On these occasions, Mrabet plays the mischievous jester; he is the performer, the prodigy and protégé. He thrives on attention. Bowles is the observer, reserved, reticent, restrained. Bowles seems, as Birgit remarks to me, rather like a fondly indulgent parent where Mrabet is concerned. (Bowles is without offspring, Mrabet was thrown out of his home by his father.) Or is their friendship something on the order of that between Ishmael and Queequeg?

Mrabet’s tales often begin firmly anchored in a realistic, recognizable world with details of place and time, then take a surreal turn and become strange, poetic fables. For example, he begins: “I used to work at the docks unloading the ships and every morning I drank my coffee and ate my pastry at the same café and every morning the same woman passed by.” Mrabet then introduces into the story the image of a hair in a box worth 10,000 francs, a boat built of smoke, a talking tree.

We view a portfolio of Mrabet’s paintings and drawings which is owned by or stored with Bowles. The motifs are rendered in contrastive colors and intricate detail, creating a hallucinatory effect. There are faces, snakes, eyes, plants, birds, animals and spirit entities. The visionary, mythic quality of the work brings to my mind the art of the Huichol and the Tarahumara in Mexico.

When I mention the Tarahumara, Bowles says that he once translated some Tarahumara myths for a surrealist magazine. He rummages in his bedroom and returns with a copy of View for May 1945, a special “Tropical Americana” number which he edited. There are black and white photographs, collages and translations, including sections of the Popul Vuh and the Chilam Balam, all done by Bowles. A myth titled “John Very Bad” has been rendered by him into English from the Tarahumara. There are also bizarre and gruesome news stories selected by Bowles from the Mexican press.

Bowles speaks of the extreme poverty and squalor he encountered in parts of Mexico when he visited that country in the 1930s. Mexico was a land of gloom and chaos, he says, but also poetry, mystery and great natural beauty. Places such as Acapulco and Tehuantepec were very pleasant in those days and living there was very cheap. Yet he was often very ill in Mexico, afflicted with diverse ailments.

I ask Bowles if he ever thinks of returning to the countries he visited as a young man or of traveling to other regions of the globe. He dare not leave Morocco, he says. He is afraid that if he leaves the Moroccan authorities will revoke his residence permit or will not renew it. The reason for this state of affairs, Bowles explains, is that his books and his translations have offended elements of the ruling elite of Morocco. They have concluded that some of his fiction and the works he has translated by Larbi Layachi, Choukri and Mrabet reflect ill on Morocco. The authorities have succeeded in banning the sale of certain of these writers in Morocco. Copies of their books have been confiscated by the police and destroyed. It is a very sensitive issue. The western-educated political elite refuses to acknowledge that such conditions and such people as portrayed in these writings still exist. The ruling elite wants to promote abroad the image of Morocco as a modern country.

If he were to be expelled from Morocco or denied re-entry, he would not know where to go. Everywhere else seems unappealing. Even though Tangier has certainly changed for the worse over the years, he says, it still remains far less objectionable than any other place he can imagine.

In this regard, I mention that we found Madame Porte’s café (a Tangier landmark) closed this afternoon but there was no indication whether the closure was merely temporary or permanent. Ominously, though, the café looked abandoned. An elegant place, Bowles says, with excellent cakes and cookies. Madame Porte was rumored to have been a collaborationist, he adds. “I put her into Let It Come Down, she says Guten abend.”

I mention to Bowles that, like him, I am an admirer of Kurt Schwitters and his Merz collages. Bowles brightens at the mention of Schwitters. “I stayed with him and his family in their apartment in Hannover,” he recalls. “I even helped him to gather materials for his collages.” He esteemed Schwitters as an independent spirit and a man of creative integrity. Inspired by one of Schwitters’ sound poems, Bowles says, he wrote a passage in a musical composition titled Sonata for Oboe and Clarinet.

Another artist whose work Bowles admires, he tells us, is the French painter, Jean Dubuffet (not to be confused with Bernard Buffet). He finds in Dubuffet’s paintings a subversive spirit akin to that of Schwitters. Both Schwitters and Dubuffet can be credited with originality and authenticity in their response to the myriad horrors of the modern world. Certain affinities, he says, can also be seen between works by Dubuffet and those of Mrabet, and, indeed, the art of the Tarahumara and others. Such works seem to have their origin in a common state of consciousness or mode of perception, in secret and mysterious resources of the mind.

We observe that we find it curious that none of Bowles’ stories or novels have ever been filmed. This is strange since so many works by his literary contemporaries have appeared in film adaptations. Have screen rights for any of his fiction been purchased? Bowles replies that of his four novels he has sold the screen rights to all but The Spider’s House. The screen plays for The Sheltering Sky, Let It Come Down and Up Above the World, had, however, all been very badly written and no-one was interested in filming them. Bowles says that he is entirely content with this state of things because at the time that he sold the screen rights, “my wife was very ill,” and the money he received was welcome. Perhaps, too, it is just as well that none of the novels have ever been filmed, he adds, since you can’t know what the director will do with the characters and the story. After selling the screen rights the author has no rights whatever concerning the cinematic adaptation of his work. He had once accompanied Tennessee Williams to a screening of Boom, (a film based on a play by Williams) and Williams had been appalled and depressed by what the director had made of his play.

Bowles smiles with grim amusement in telling us that in the contemporary world movies and show business would seem largely to have supplanted literature. His own literary agents in New York, he says, now describe themselves on their letterhead as “Agents to the Stars.” This minor but telling alteration from a literary agency to an entertainment agency serves to confirm his impression that every value is eroding, everything is deteriorating, everything is growing more and more degraded. His smile indicates that he believes nothing can be done to resist or prevent this process. Silently, I reflect that perhaps the title of his second novel might serve as a kind of collective title for all his work: Let It Come Down.

Paul Bowles has been to us a most generous, courteous and considerate host. Whatever private terrors or obsessions he may keep in check beneath his impeccable dress and urbane manner may be guessed at from his fiction. Concerning the man, I have no insights to offer, only a few observations made on the basis of brief acquaintance. My impression of Bowles is that of a patient, tolerant, gracious man, who despite his fundamental pessimism and sense of futility endeavors to live according to a precise personal code, evincing fortitude, humor and a forbearing nature.

We sail back to Algeciras on the Ibn Batouta, leaving behind us the white city of Tangier. White gulls wheel behind the boat and a school of dolphins leaps in the sunlight. At last only the tower of the new mosque is visible and then that too is gone.

Postscript: Many years later I was saddened to read in a piece in the TLS that Bowles and Mrabet had had a falling out and were bitterly estranged from each other. I don’t know if they were ever reconciled. Paul Bowles remained in Tangier until his death in late 1999. Mohammed Mrabet continues to live in Tangier. His artworks have been widely exhibited in Europe, the United States and North Africa and collections of his stories continue to appear in English and French translation.

Spyros Meimaris says

A wonderful report on Paul Bowles and Tangier, also of Mohamed Mrabet. Gregory Stephenson writes simply and concisely, transmitting the feel of Moroccan every day life, it’s air of Old Testament ways and times. Everything pertaining to Bowles and his books is very important to me, because I had the chance of visiting him back in 1961, and being impressed by his demeanor, his gentleness and if I may say his embodying the American male beauty of the time. I had also met Jane at that time, with whom I had an enlightening conversation. Stephenson’s recitation is very lively and I enjoyed it greatly, since it reminded me of Morocco and Paul, who is one of my favorite modern writers.

Gregory Stephenson says

So very sorry I only just now discovered your kind comments. I know and admire your poetry! Thank you very much!

Gregory

Mike Ballard says

The Rolling Stones are in town and I can’t afford a ticket. Besides, who would want to be amongst folk who can afford $300 for the ‘cheap’ tix. Still, I can sit here and romp around the clock with Paul Bowles and perhaps smoke a little kif.

Thank-you.

Gregory Stephenson says

Oh dear, I just this minute discovered your comments. Thank you very much. A little kif right now would not be amiss. Gregory