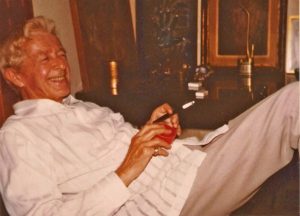

A friend of mine is so artistically fascinating and creative that labeling him “eclectic” or “multi-faceted” understates his cultural contributions. Full of life, he incessantly looks for beauty in all that surrounds him. The following is his story, plus an interview I conducted with him prior to his June 4, 2003 appearance in Chicago. We sat down to discuss his life and his work, and to meet someone special. As a gift to him, I had invited another friend of mine to that night’s show, a surprise guest that turned the event into a reunion that excited every person in the room.

The 1950’s, a decade known its political conservatism and social conformity, ironically produced avant-garde musicians, novelists, poets, and painters who set the stage for the turbulent 1960’s. New York City was the artistic capital of the world in the 1950’s, home to one small group of musicians, writers and painters that hung out with each other almost nonstop, their lives an endless party of passionate performances and discussions. This set of friends vowed to never stop creating, regardless of the setbacks that might occur in their lives. Though ninety-nine percent of what they shared consisted of the moment, the other one percent would be written down, recorded, filmed, or reported, and become the basis for how the world would judge them. The group’s consensus regarding that one percent became their motto, “By your works ye shall be known.”‘

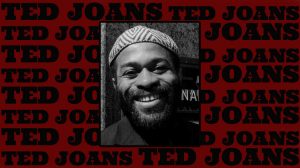

One member of the group was a young man from rural Pennsylvania, full of wanderlust and hungry to experience life and create music, who had already lived in Paris, France, but had settled in New York City. A French horn player proficient in both jazz and classical music, David Amram had his own jazz band, was composing symphonies, chamber music, and choral works, and budding as a conductor.

Amram’s skills at improvising words and music led to a close friendship with an author who would soon become known around the world, Jack Kerouac, who had grown up in Lowell, Massachusetts and initially came to New York City to play football for Columbia. Kerouac possessed improvisational skills similar to Amram’s, along with the ability to create countless characters with his voice. A natural pairing, David and Jack began performing together at parties, the beginning of a collaboration that lasted fourteen years and ended with Kerouac’s death at the age of 47 in 1969.

Kerouac became famous in 1957 upon the publication of his second novel, On The Road, followed by other many other books, including The Dharma Bums, The Subterraneans, and Big Sur. He was named by Writer’s Digest in 1999 as one of the 100 Best Writers of the 20th Century, but is most famous as the unofficial leader (an unwanted title) of the Beat Generation, a literary movement with varying definitions but generally categorized as a group of disaffected post-World War II American writers who, in Kerouac’s words, were “intent on joy” and possessed “wild selfbelieving individuality.”

The Beat movement introduced hipsters to the mainstream, then spawned an offshoot lifestyle called “Beatnik,” which was little more than a fad and abhorred by the Beat founders. Kerouac’s 1958 novel, The Dharma Bums, was the seed for a more lasting legacy of the Beat philosophy, for it prophesied the rucksack revolution that occurred several years later in the psychedelic 1960’s. Kerouac was the granddaddy of “hippie,” and became revered by the counterculture.

Amram and Kerouac, close friends from 1956 until 1969, shared a zest to experience all that life had to offer, finding beauty in aspects of everyday existence that others might find nondescript. Part of experiencing all facets of life was experimentation with drugs and alcohol, but Amram soon slowed down the partying, went on a health kick, and stayed healthy to this day. Unfortunately, Jack became enslaved to chemicals, dying young due to alcoholism. David states in the foreword to his latest book, “If there had been the awareness that alcoholism was a disease… Jack would probably be here with us today.” As for himself, David says, “If I had continued along that path, I would not be alive today to write this memoir.”

David Amram is undeniable proof that creativity can thrive without chemical inducement. The 72-year-old conductor, composer, multi-instrumentalist, actor, and author has maintained a staggering pace of composing and performing over the past 50 years, resulting in an enormous body of work. He has composed over 100 orchestral and chamber works and written two operas. His theatre and film scores include the classic movies Splendor In The Grass and The Manchurian Candidate.

Appointed by Leonard Bernstein in 1966-67 as the first composer-in-residence with the New York Philharmonic, he is listed by BMI as one of the Twenty Most Performed Composers of Concert Music in the United States since 1974. James Galway, the world’s most famous flutist, recently commissioned Amram to compose a concerto for flute and orchestra, “Giants of the Night.” The work, a tribute to Amram’s friends Charlie “Bird” Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Jack Kerouac, was based in classical format and modified with jazz and Afro-Cuban rhythms. Praised as work of genius for its breadth of conception and blend of musical styles, Galway premiered the piece on September 14, 2002 with the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra.

Besides writing the score (chamber music and jazz) and co-composing the title song for the famous experimental film Pull My Daisy (1959), Amram himself was the subject of the award-winning documentary Amram Jam, which will be released on home video in 2003. His video Origins of Symphonic Music, released by Educational Video, is in over 6,000 schools throughout the US and Canada.

His television appearances, besides the lauded PBS concert programs Soundstage and Austin City Limits, include Late Night With David Letterman, The Today Show, Good Morning America, and CBS Sunday Morning.

His first book, the autobiography Vibrations, was published in 1969 and became a best-seller. His second book, Offbeat: Collaborating With Kerouac, was published in 2002, receiving glowing praise from luminaries such as distinguished novelist Frank McCourt (Angela’s Ashes), noted historian Douglas Brinkley, and famous poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

In addition to the aforementioned Kerouac, Bernstein, Gillespie, and Parker, Amram has collaborated with such notables as Lionel Hampton, Elia Kazan, Dustin Hoffman, Arthur Miller,

Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, and Willie Nelson.

A sampling of the critical praise for his outstanding career includes the Washington Post‘s assertion that, “David Amram is one of the most versatile and skilled musicians America has ever produced.” The New York Times said, “David Amram was multi-cultural before multi-culturalism existed,” and The Boston Globe described him as “the Renaissance man of American music.”

Not only does Amram continue to compose music and write books at the age of 72, he shows no sign of slowing down his performing schedule. In concert, both as guest conductor and performer, he often combines jazz, Latin American, Middle Eastern, Native American, and folk music of the world, in conjunction with the European classics. He plays French horn, piano, guitar, numerous flutes and whistles, percussion, and a variety of folkloric instruments from 25 countries. Amram performs at folk festivals, provides workshops for young people and children, and appears often (seven times at last count) with good friend Willie Nelson at Farm Aid.

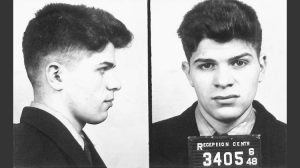

David Amram usually performs several times a year in Chicago, both solo and with his quartet, and as guest conductor of The Chicago Symphony and The Grant Park Orchestra. His latest appearance in Chicago occurred June 4, 2003 at the Hot House, a four-hour event that was typical Amram in its versatility and spontaneity. The show featured both veteran (Larry Combs, principal clarinetist with the Chicago Symphony) and young (members of the International Contemporary Ensemble) performers, a variety of Amram compositions, readings from Kerouac’s works, and a jam session. Just before the show began, a special guest entered the darkened venue. The audience was unaware that Joe Kerouac, Jack’s cousin, had arrived at the Hot House to meet and visit with David.

Midway through the evening’s performance, David introduced Joe to the audience, followed by Joe reading a few paragraphs from one of Jack’s books, accompanied by David on the piano. Joe’s lyrical voice (like Jack’s in its musicality) and haunting looks (the picture of middle-aged Jack) mesmerized the audience. The last thing people had expected to see that evening was another Amram/Kerouac pairing, forty-seven years after David and Jack first met!

The show was fantastic and the Kerouac appearance was thrilling, but the evening’s highlight occurred when David Amram graciously took time before the show to discuss his career. Quite the raconteur, hearing him tell stories was like an excursion back to the loft parties in 1950’s New York City; his voice simultaneously hypnotic and vibrant, his mood ebullient, the air crackling with creativity.

Interviewer: You’ve played with jazz icons as well as the world’s finest classical musicians, you’ve performed nearly every musical genre imaginable … To what do you attribute your eclectic taste and prodigious output and creativity?

Amram: As we speak here in Chicago, at the Hot House on Balbo Street, June 4, 2003, I’m fortunate at this point in my life to be able to do and to re-do a lot of the things that I spent a good part of my life learning, studying, and being part of.

My uncle, David Amram, whom I was named after, was a merchant seaman. He traveled all over the world, and when I was brought up on our farm in Feasterville, Pennsylvania, he gave me a picture at a very early age that the world was a big place, a lot of people spoke different languages, played different kinds of music, had different histories, and they had a lot to offer. And everything from our own Native American music to old and beautiful music, and languages, and food, and ways of life that people brought over with them from the old country all were part of something that as Americans we can partake in.

As a merchant seaman, he was able to see and learn about and enjoy, because he not only partied up a storm when he went into ports, he also stayed sober a good amount of the time and checked out people, the languages and food and music and places. So when I met Jack Kerouac I felt right at home because he had also been a merchant seaman. In fact, at tomorrow night’s poetry reading in San Francisco, aside from Michael McClure, Floyd Red Crow Westerman, and Neal Cassady’s son John Cassady and a lot of famous poets, we have a merchant seaman, Stephen Barry, who’s a full-time merchant marine who writes poetry who’s going to be reading with us.

I think that musicians, like merchant seamen and airline pilots and people of that nature, are blessed that we can travel and go different places and experience different things and see different people…and the blessing of that is that when you come home you try to share that with your family and your friends, and you get more respect for your own heritage and everyone else’s by celebrating the fact that there is such a thing; that we’re all just not the products of junk fast-food style of music, junk fast-food movies, etc. I mean, I enjoy, I try to enjoy everything, but there’s a lot on the plate besides what we’re told is the only thing that’s supposed to be fashionable at the moment. There’s a big world out there. With the Internet and the World Wide Web you could go between the cracks of the industrial entertainment and education and see all the treasures that are there.

Interviewer: You and Jack seemed to be very psychically connected. How did your friendship with Jack influence your body of work and your life after he died? What effect did his death have on you?

Amram: Well, we had such a great time collaborating together and dreaming together, things we wanted to do and things we did do, I thought I would continue on my path of what they called the “trail of beauty.” The Navajo Prayer of the Twelfth Night refers to being on a trail or path where all the beauty that surrounds us every day, the prayer of beauty above me, beauty beside me, on the trail of beauty, therefore I am. That’s a rough translation; you can’t really translate from Navajo. But it’s the fact we’re surrounded by what The Creator gave us that is so beautiful and so precious and sacred, and to enjoy every precious minute of life and what is already here was something that he (Kerouac) used to do and what he called finding the “diamonds in the sidewalk.” We would walk down some dirty looking street in Greenwich Village with all kinds of newspaper wrappers and old …remains and junk, what we considered to be junk, and he’d say, “Look at the diamonds in the sidewalk,” meaning “look at the beautiful things that just sparkle right in that sidewalk,” on a street that would be considered to be something you wouldn’t even want to look at. It was beauty that was around us, and to celebrate that, and not only celebrate the street corner or sidewalk, but celebrate nature and people and all of the things in life that are there that we very often overlook.

I continue to try to understand and appreciate the beautiful way that people speak and the beautiful ways that people create music, and talk to one another, and the way people move, the wonderful food that different people cook and eat, and the creativity with which so many people deal with adverse situations in life, and however difficult that is work, I always remember to count my blessings. That was something that Jack did very, very much, and even though he had such a hard time at the end of his life, he was always, especially with his old friends, really positive to be around.

Interviewer: Speaking of old friends, I’ve read Offbeat several times, and I was very moved by your relationship with (poet) Gregory Corso before he passed on. You seemed to be a big help to Gregory while he was terminally ill. Right now, the only surviving members of that era are Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Carolyn Cassady, some of those people, and you continue to collaborate with all of them, don’t you?

Amram: Yeah, I’ll be with Lawrence Ferlinghetti tomorrow night at City Lights Bookstore 50th Anniversary, I’ll be with Carolyn Cassady next Monday in Paris, and I’m going to be with her son John Cassady tomorrow night. We’re still friends and they’re still very inspiring people. Carol is 80 and Lawrence is 83. I’m 72, I’m the youngster of the group.

(Pause, as he looks over the interviewer’s shoulder and sees a familiar-looking face)

I figure that’s Joe Kerouac!

Interviewer: Joe Kerouac just joined us, Jack’s cousin. Doesn’t he look like Jack?

Amram: Yeah, I looked right away and thought, “Boy, that might be Jack.”

(Pause for introductions, and Joe joins the table for the rest of the interview)

Interviewer: How did you get involved with Farm Aid?

Amram: Well, I was playing with Chicago’s great Steve Goodman many, many years at the Earl of Old Town and different folk festivals. He was in Texas and he called me up and said, “David, I’m playing at the Opry House in Austin,” and he said, “I know you’re with the Corpus Christi Symphony. If you can get a day off, I’ll give you a plane ticket and you come and play with Jethro Burns,” great mandolin player… I said to… the director of the Corpus Christi symphony… “I was invited by my great friend Steve Goodman to play with him, on the two days I have off from rehearsing with the symphony, at the Opry House in Austin.” She said (changes to southern accent), “Dave, they don’t have any opry house in Austin.” (reverts to his regular voice) I said, “No, no, it’s not an opera company, it’s a country music place.” She said, (goes back to southern accent) “Well, if you’re back on time, that’s fine with me. You’re free those two days and you’re a grown man, just be sure to be back on time for rehearsal.”

So, I went to the Opry House, and we were playing, Jethro and myself, and this guy came up, with a headband on, long hair, and started singing harmony parts with Steve and Jethro. He was fantastic! After it was done, I said, “Jethro, who was that guy singing those harmony parts?” He said, “That’s the owner of the club, Dave, that’s Willie Nelson.” I had seen Willie years before that, when he was dressed up in a suit and tie and short hair. I didn’t even recognize him.

Interviewer: The Nashville Willie.

Amram: Yes! So we went back and sat in a room with him and Jethro and Steve, all night long, but I did manage to get my plane back next day. I didn’t get much sleep. Then I was playing in Austin at the Paramount Theater and conducting a chamber orchestra with Jerry Jeff Walker, and also played guitar and played the pennywhistles and sang, did that as well as conducting the orchestra, and Willie was there with Grady (Martin) the great guitar player who played with him. Willie, he says, “Man, I love that. We don’t have any orchestra at Farm Aid but will you come and play the guitar and pennywhistles and play with our band?” So, I was invited to Farm Aid, and that was seventeen years ago and I’ve been doing it ever since. In fact, I’ll be playing with Willie in Connecticut this June 21.

Interviewer: That’s a great story, it highlights your eclecticism. I remember seeing you on TV conduct an orchestra for a Jerry Jeff concert for Austin City Limits.

Amram: My gosh, yeah that was after I did the one (first Farm Aid) with Willie.

Interviewer: Can you tell me about your family’s involvement with the new play that’s based on Joyce Johnson’s correspondence with Jack?

Amram: Yeah, it’s called Door Wide Open and it took place 1957-1958. My daughter, Adira, who’s 22, plays the 22-year-old Joyce Johnson. I knew Joyce when she was 22, and Jack, and we all hung out together, so to sit a block and a half from the old Five Spot where Jack used to come and sit in and play with my band…and be…with my daughter playing Joyce and John Ventimiglia from The Sopranos playing Jack so well (if I closed my eyes I would think it was Jack) was just such a wonderful experience.

Then the play got to be so good that I forgot about all that, and each night I would go to the play I would just see those characters as what they were in the reality. That’s the amazing thing about art-if it’s really good it takes you out of even yourself and people that you know and even your own family. I watched my daughter, I forget she’s my daughter… the guy who’s playing Jack was someone who’s Jack, whom I knew and still think about all the time. It’s doing really well and they’re going to do it, I think, in several other places now.

Interviewer: Your energy, your enthusiasm, your creativity is contagious. At the age of 72, how do you keep up this constant travel, performance, and creativity? Where do you get the energy?

Amram: Well, it’s something I always dreamed of doing. It’s something I always wanted to do and something I hoped I would get the chance to do. Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, and the great conductor Dimitri Mitropoulis and classical people and painters like I wrote about, Franz Kline and all these older people that I knew, who are older than me, all had that. They loved what they were doing and they had dreams, and concern about other people, and cared about something besides themselves. So that gave me a picture of how to try to be.

Jack was very much that way – compassionate, conclusive, that’s why his books are all in print all over the world. The publishers still, at my age I regret to say, still don’t understand Jack Kerouac. They still think his sentences were too long, and he wasn’t serious enough. Of course, he had a Lowell accent, and he went to church, and he took care of his mother, and he was patriotic, and he would hang out with anybody and everybody. Therefore, how could he be a great artist if he was just like a normal person?

(Speaks a short sentence in French before continuing) He spoke French fluently, too, because that was his first language. I was just in Canada at the Montreal Festival, and I speak French, too, and we had a whole part about his French-Canadian background, which is such a great heritage. The fact that he had to come into the country (U.S.) and be in a place where he was not appreciated made him appreciate America more, and he saw the country with the fresh eyes of someone who could see the beauty part.

I try to do the same thing myself. I just see all of this in terms of the same way that Jack looked at it, and the way Dizzy Gillespie did know him and a lot of other people who aren’t necessarily well known, and have a love of life (speaks short phrase in French), a joy of life, and an appreciation for that.

Also, trying to show young people that they can succeed and work hard and be involved and not have to give up, and to strive for excellence and to care about other people, and do all of those old-fashioned things that aren’t part of the official plate. If you watch network television, you’d assume everything’s down the drain. My own personal feeling is the entertainment industry and a lot of the cultural manifestations of our time are going down the drain, (but) I see an army of young people like these great musicians here tonight who are doing phenomenal work, and a younger generation of people that are more educated, more intelligent and have more to offer than ever. So I feel an obligation for them to show that there are some old folks who care not only about ourselves, but about our own children and our grandchildren. I want to see them get out there and do something good!

I say to old people my age, septuagenarians, all the folks over 70, to try to get out there and hang out with kids and show them all of the stuff that we were blessed to get from the people that were older than us, and share in your knowledge. Whether or not society tells us we’re just supposed to pick up our Social Security check and go to Florida and cool out, we have a lot to offer. I think, more and more, the educational system is beginning to see that we can use our older people as a resource to give our younger people something of beauty.

Interviewer: Amazing response, which prompts one final question. Jack’s tombstone said, “He honored life,” and, boy, you’re showing that by what you’re doing now. I noticed in your book that some of you and some of the people you collaborated with had a saying, “By your works…”

Amram: (finishes interviewer’s sentence) …(Y)e shall be known.” Right. That’s from the Bible. Could I read one thing that Jack himself wrote? Grey Fox Press put it out, and I told John Sampas (curator of Kerouac’s estate) when I read this that I wouldn’t be, I’d be saying it in a way that hopefully wouldn’t be violating his copyright, but it’s so beautiful. It was his (Kerouac), what he felt about being Beat…. what Jack said about Beat when he was asked by an interviewer, in a very negative way, what it was and why he didn’t seem to be like a Beat person, because he wasn’t just sitting around and complaining, and didn’t seem to fit into the image of what Beat was supposed to be. This is what Jack himself said:

“…I want to speak for things, for the crucifix I speak out, for the Star of Israel I speak out, for the divinist man who ever lived, who was a German (Bach), I speak out, for sweet Mohammed I speak out, for Buddha I speak out, for Lao-tse and Chuang-tse I speak out, for D. T. Suzuki I speak out…why should I attack what I love out of life? This is Beat. Live your lives out? Naw, love your lives out.”

David Amram was still going strong at 11:30 that evening, despite leaving at 6 a.m. the next morning for San Francisco, then onto Texas for the Kerrville Folk Festival, followed by a week in Paris as a headliner for a festival (“Lost, Beat, and New,” the Literary History of Twentieth Century Paris).

After the Paris trip, I received a “short” three-page e-mail about the festival, life in modern-day Paris, and David’s trip to a club where he and his quartet performed during his youth. In his words, “It was a wild feeling for me, as the returning kid musician of the 1955 Paris scene, finally coming to the place where I played at nearly fifty years ago, and now speaking as some kind of elder statesman to all the people in the bar about what it was like before they were born!” Indeed, elder statesman David Amram keeps speaking, and the world keeps listening.