As part of their reading tour through a dozen European countries, poets Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky, and their musical accompanist Steven Taylor, arrive by train in Copenhagen in the chill dark of an afternoon in early January of 1983. Birgit and I welcome them with red tulips and after shaking hands help them to carry their baggage from the platform upstairs and through the station to a taxi.

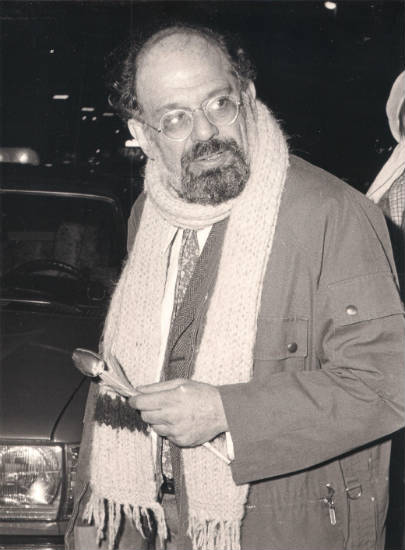

Allen is hatless, bespectacled and balding in a coat and muffler. Beneath his coat he wears a tweed jacket and sports a flowered necktie. His forehead is furrowed, his graying beard neatly trimmed, his right eyelid and lip drooping with a palsy with which he had lately been afflicted. Peter – despite the winter cold – is dressed in a yellow t-shirt emblazoned with the Naropa Institute logo and light cotton trousers. His feet are bare in a pair of flip-flops, his abundant graying light-brown hair worn in a long ponytail. His arms are muscular, his belly prominent. Allen says that they have come up in the train from Holland, haven’t slept, and are very tired. They are going to be interviewed by a reporter from the Danish newspaper Politiken at their hotel and then in only a few hours hold their scheduled reading.

Peter walks the platform in a curious, crouching fashion, grimacing, groaning, grunting, but in a hoarse voice he politely inquires as to where I am from and what I do. We struggle together up the stairs to the main floor of the station bearing a large and very heavy cylindrical cloth bag. When we reach the top of the stairs, Peter suddenly lifts the bag in one hand and to the astonishment of onlookers begins to spin with it, pirouetting around and around across the floor of the railway station. From the outset, there is something in Peter’s manner and behaviour that calls to mind the figure of Kaspar Hauser, an innocent abroad in a harsh and sordid world.

The reading is scheduled to be held in Huset (The House), a hip cultural center established in a former factory. A venue for music, theatre and other performances, Huset also contains a natural foods restaurant and a cinema. This evening there is an unforeseen problem. Shortly after Birgit and I arrive to claim our tickets and gain admittance to the reading, the entrance to Huset is blockaded by members of the Youth Club Personnel Union in protest at some grievance. The picket line (a solid phalanx of young people) is physically denying entrance to Huset to any and all patrons. (This despite the fact that the personnel who work in Huset have voted not to support the strike.)

When I catch sight of Peter, Allen and Steven in a hallway of Huset, I apprise them of the situation. Allen is thoughtful, not wishing to violate a picket line but not wishing either to disappoint those patrons who have come to hear them perform. We ascend together in an elevator to the room where the reading is to be held, a café with a small raised wooden stage. As Allen enters the room, there is applause from the approximately fifty guests who (like Birgit and me) arrived before the picket line was established. Before Allen can speak, though, a tall, thin young man with a sparse, scraggly beard and a shaven skull stands directly in front of him, raises his arm in a Nazi salute and shouts: “Heil Hitler!” Allen calmly ignores him and addresses the audience. “There is the question of the picket line to be considered,” he says. He offers to go down to the entrance, attempt to reason with the pickets, and failing to persuade them to alter their course, he will deliver a brief reading for the congregation of about 150 aspiring, frustrated patrons who are waiting there in the winter cold. (Meanwhile, the madman continues to yell: “Heil Hitler!”) The audience encourages Ginsberg to do this and he leaves the room.

Orlovsky remains, still dressed in his Naropa t-shirt, and now with a blue denim cap on his head. He paces barefooted and stiff-legged around the room, grunting and groaning. He dances on tiptoe, he approaches an elderly man seated at a table, shakes his hand and kisses it. He begins to brush his teeth, then brushes his long hair. He picks up a brass megaphone, balances it on one hand, holds it in his mouth by the handle, places it on his crotch like a giant erection, falls to the stage, pretending to writhe in ecstasy. He uses it as a telescope surveying the room, then employs it to amplify a series of animal noises: a dog barking, a rooster crowing. The audience cackles at these madcap antics. Peter kisses the wall, grows ever more passionate in his kisses, pats it, humps it. He lights a cigarette, resumes brushing his teeth, takes a swig from a bottle of Carlsberg. He then begins to wipe the stage curtains with a paper tissue. Meanwhile, Steven Taylor, a bespectacled, sensitive and intelligent looking young man, unpacks a guitar and begins to strum classical chords.

At length, Allen returns to the stage, explaining that everyone, including the pickets, has been invited up to the reading, but the pickets have not accepted that solution, so there’s no more to be done. He unpacks his portable, hand-pumped harmonium and begins to chant in a baritone voice: Aaaaaaaahhhhhhhhhhh. The chant rises and falls in the room, expressive of an infinite sorrow, an infinite longing for solace and refuge. He is joined in his chant by a suddenly serious Peter Orlovsky and by Steven Taylor who plays guitar chords behind the drone of the harmonium. The chant finished, Allen opens a black binder and reads “Birdbrain,” a serio-comic poem condemning and lamenting the myriad manifestations of human selfishness and folly. The microphone is not working so he shouts the poem. The madman continues to shout at intervals and to applaud at incongruous moments. In response, Allen improvises lines incorporating the poor obnoxious man into the poem: “Birdbrain applauds at the wrong time.” He also alludes spontaneously to Peter now yodelling alone somewhere in the distance beyond the room: “Birdbrain yodels in the corridors of the Huset.” And he mocks his own reading of the poem: “Birdbrain keeps reading his poem no matter what interruptions there are.”

Allen reads a poem on the death of his father, Louis Ginsberg, titled “Don’t Grow Old.” He recounts how his aged, ailing father, reduced to the state of an infant to be bathed, lifted and laid in bed by others, ruefully remarked to Peter: “don’t grow old.” Allen also relates how he read poetry aloud to his dying father, including Wordsworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality.” As he pronounced to his father Wordworth’s lines concerning how at birth the human soul “cometh from afar / Not in entire forgetfulness / And not in utter nakedness, / But trailing clouds of glory do we come / From God, who is our home,” his father sighed deeply and said to him: “That’s beautiful, but it isn’t true.” Now, harmonizing with Steven, Allen sings a melancholy composition called “Father Death Blues.”

At intervals, throughout the reading of poems and the singing, the madman in the room continues to voice loud and enraptured “heil Hitlers.” Once, Ginsberg stops and with patient weariness addresses the man, saying: “Please let me read. Please don’t interrupt me. The poems are quiet.” There are further songs, “The Little Fish Devours the Big Fish,” and the lively “Do the Meditation Rock,” and further poems, “The Black Man,” “What Are You Up to?” and “Libellous Poem.” To all of these, the Danish audience responds with much applause.

Then Peter, who has been smoking, staring and musing the while, reads from his own collection of verse, the scandalously titled Clean Asshole Poems & Smiling Vegetable Songs. Peter sits wide-legged on a chair, holding his book in his right hand, while with his left hand lifted in the air he gestures delicately, moving his fingers somewhat in the manner of a flamenco dancer. As Peter reads, Allen sits to one side of the stage, nodding approval, smiling, intent. Peter’s poems include “First Poem,” “Second Poem,” “Dream, May 18, 1958,” “Leper’s Cry,” “Someone Liked Me When I Was Twelve,” and “Write It Down Allen Said.” These are poems of buoyant whimsy, exuberant invention and deep seriousness. They are the poems of a guileless heart utterly bewildered by human cruelty and the world’s deceit. Peter reads them with touching sincerity in his raspy voice. The audience reaction is enthusiastic.

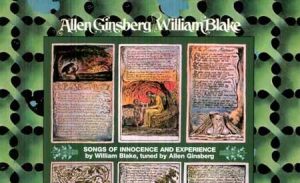

There is an intermission, after which Stephen and Allen sing a country blues titled “When You Break Your Leg,” and, joined by Peter, sing William Blake’s “The Tyger,” for which Allen has composed a melody. Then, Allen reads “America,” (pausing occasionally in the course of his reading to explain to the audience certain allusions in the poem, such as references to the I.W.W., Tom Mooney, and the Scottsboro Boys, and improvising additional lines pertaining to current political events concerning President Reagan and Iran.)

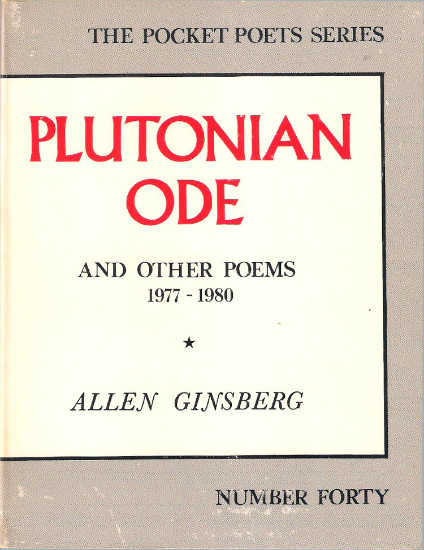

The final poem of the evening is “Plutonian Ode.” Alan stands, holding the recently published City Lights book of that title in his left hand, gesturing as he reads with his right hand, raising his right index finger like a teacher, closing his fingers in a fist, his body rocking, his shoulders shrugging, his hands trembling. (Orlovsky sits on a chair beside the stage, gaping enormous and protracted yawns.) As Ginsberg begins part II of the poem, he drops the volume of his voice, reads calmly and tranquilly, then for the third and final section of the poem, builds force and volume, tension, drama, passion until the last syllable sound, resolving all in sorrow and affirmation: “Ah!”

There is a gasp from the audience, then cheers and ardent and sustained applause.

The evening’s performance ends with Allen and Steven singing Blake’s “The Nurse’s Song,” while Peter yodels his accompaniment. The audience is exhorted to join in the refrain, “and all the hills echoéd.” The audience is warm and gracious in its extended final round of applause.

The poems and the musical pieces are effectively paced and well-proportioned, complementary, rather like the balance between hymns and sermons in some church services. Indeed, the reading or performance taken as a whole bears some resemblance to a kind of ideological-cum-spiritual rite or ceremonial observance for the adversarial culture. A common denominator among the songs and poems performed is a summons to awareness, to resistance, to dedication. The audience is encouraged to learn to meditate, to reflect on the brevity and vanity of life, to oppose the forces and agencies of injustice and oppression, and to practice the virtues of “patience and generosity” (as expressed, for example, in “Do the Meditation Rock.”) For a poet considered by many to be avant-garde, irreverent and indecorous, Ginsberg seems in many ways closer to Vachel Lindsay and Carl Sandburg than to his hero Rimbaud or to his mentor William Carlos Williams. In his dramatic energy and his impassioned idealism echoes can also be heard of the populist prophets and militant labor orators of the American past. (I’m thinking of figures such as William Jennings Bryan and John L. Lewis, among others.) The physical voice in which Ginsberg brings his poems to life before the audience is familiar to me from tapes and records, a resonant baritone with east coast American inflections, his delivery richly cadenced, by turns conversational and incantatory. He is an expressive reader of his own poems, clearly aware that sound in poetry is integral to meaning.

Eleven days later we attend a second evening of readings and songs, held at Lyngby Storcenter, an American-style shopping center located in the town of Lyngby, north of Copenhagen. In the interim, Peter, Allen and Steven have given a series of performances in towns and cities on the island of Funen and on the Jutland peninsula. Birgit and I arrive early and run into Allen at a snack bar. He says that he has just returned from a visit to Christiania (a self-proclaimed, self-governing “free town” within the city of Copenhagen, an abandoned military installation occupied in 1971 by slum-stormers, hippies and anarchists). The place reminded him, he says, of the slums of India. Allen looks professorial, dressed for the evening’s performance in a green tweed sports jacket, a red-striped shirt and an iridescent, multi-colored tie, gray wool trousers, black socks and scuffed black loafers. At my request, he signs and inscribes my copy of Plutonian Ode and Other Poems, expressing his thanks for our having printed the title poem in our literary journal, Pearl (No. 6, 1978). Orlovsky joins us ordering a cup of coffee. We shake hands and he raises my hand to his lips, kissing it. His eyes are a clear blue. He is dressed as before in an orange Naropa Institute t-shirt, beads, bare legs in long blue shorts, bare feet in thongs, a blue denim cap atop his head. As he drinks his coffee, he takes a pull on a small bottle of Danish schnapps he has bought. He asks me sincere questions about my job and my marriage. He tells me that he and his Spanish-speaking girlfriend will be having a child. When? I ask. In two years, he replies. He speaks to me of the farm where he lives, of the nuts and vegetables that he grows there, of the bees and goats that he tends. He says that he is not a good farmer, however, as he takes too much amphetamine. Peter signs my copy of Clean Asshole Poems and Smiling Vegetable Songs. He encourages me to meditate, a practice, he says, “invented by Lord Buddha 2,500 years ago,” and recommends to me The Jewel Ornament of Liberation by Gampopa and Chogyam Trungpa’s The Myth of Freedom and the Way of Meditation. These books are very valuable, very useful, very good, Peter says.

Fortunately, the Nazi madman does not attend the performance at Lyngby Storcenter. The reading takes place in an auditorium with a proscenium stage. The stage lighting is bright, harsh and hot. “We’ll begin with music,” Allen says to the audience and sings “Guru Blues” (“Father Guru”) with Steven, while Peter sits nearby miming slyly and rubbing lotion on his feet. The next song is “Gospel Noble Truths,” with the depressing refrain “die when you die,” the rhyming text set incongruously but not incompatibly to a country and western tune. As Allen and Steven play their instruments and harmonize with their voices, Peter yodels in support. Allen announces that Peter will read first tonight. In a hoarse, whispering voice, enunciating carefully, holding a cigarette, Peter reads “America Give a Shit,” “Write it Down Allen Said,” (miming with his hands the images of “sub-machine guns” and “confusion”) “My Mother Memory Poem,” “Signature Changed,” “4-D Man,” and “Morris.” The latter is a long and moving poem inspired by Peter’s work as an orderly at Creedmoor State Mental Hospital in Queens, New York. The poem relates the story of a fleeting moment of human rapport achieved between Peter and a severely afflicted young patient. His reading ended, Peter places the palms of his hands together in prayer-like fashion and bows to the audience (the arjali mudra or namaste, more common these days but then rarely seen in the west.)

Allen tells the audience that he is going to read some of his early poems. From his copy of Howl and Other Poems, he reads “Sunflower Sutra,” followed by a forceful, fervent rendering of “Howl,” during which he shouts and sobs, sweats and gestures. There is an intermission, and when Ginsberg returns to the stage he prefaces his performance by ringing his brass finger cymbals three times. Together with Steven and Peter, he sings “Prayer Blues” and “Airplane Blues,” then reads “America” pausing after each line while his Danish translator, Erik Thygesen reads a translation of that same line. (All the while Peter clowns behind them, making faces, sticking out his tongue.) “Father Death Blues” and “The Nurse’s Song” follow, with “Tyger, Tyger” sung as an encore in response to prolonged applause from the audience. Before performing “Tyger, Tyger” Allen explains that he has composed the tune to Blake’s poem to suggest the systole-diastole rhythm of the human heart: bum-búm, bum-búm, bum-búm. He says that if, like Blake, we ask who made the wrath of war and bombs, if we ask who made the lamb, we must answer with and from our own hearts. After the reading is over, Ginsberg, looking exhausted, hands me a piece of paper with the phone number of the Danish woman with whom they are staying in Copenhagen. He tells me to phone at about 10 o’clock tomorrow morning.

On the following morning, I phone the number Allen has given me and we arrange to meet at the Swedish Embassy on Sankt Annæ Plads, where he and Peter and Steven are applying for permission to work in Sweden. At the embassy, Allen tells me that during their visit to Christiania Peter stepped on a piece of glass, cutting his foot, and should get a tetanus shot. Peter has also lost his eyeglasses somewhere and must get a new pair today since they are leaving for Sweden tomorrow. Allen would also like to visit the National Gallery of Denmark. He asks if I can help them on these errands. Of course, I can, I reply.

When they have received their temporary working permits, Allen consults a sheaf of papers he carries in the inside pocket of his coat. This includes their day by day schedule of readings. Satisfied that the Swedish working permits will cover the dates in question, we leave the embassy and hail a cab which I direct to an optometrist on Nørrevoldgade (not far from the City Hospital for Peter’s foot and the National Gallery.) In the cab, Ginsberg mentions the translations of Sappho by Ed Sanders that I published in Pearl. We agree that they were very good. They compare very favorably, I tell him, with translations by Willis Barnstone and Mary Barnard, and with the “Poem of Jealousy” translation done by William Carlos Williams. Ginsberg is familiar with these and adds that Sir Philip Sydney’s translations of Sappho are interesting for having been written in Sapphics and Ezra Pound also had a go at writing in Sapphics in a poem titled “Apparuit.” But it was the Sanders’ translations that got him interested in the Sapphic verse form, Allen says. He says the form is complex and difficult to work with. The stanzas are composed of 4 lines each, consisting of trochees and dactyls. First three lines of two trochees, a dactyl, then two more trochees. Then comes the fourth line which is shorter, just one dactyl followed by a trochee. As our taxi moves and stops in the streets of Copenhagen, Allen recites for me his poem, “Sapphics,” as he does so counting the syllables and accents on his fingers.

At the optometrist, while Peter is tested and fitted for new glasses, Allen goes on to describe to me Ed Sanders’ invention, the “Bardic Lyre.” It’s based, he says, on the ancient acoustic lyre, the four-stringed tortoise-shell lyre, but is a small, finger-operated electronic musical instrument intended to accompany recitations of poetry. Perhaps he will himself incorporate it into his own readings, Allen says. It might enhance the speaking of certain of his poems, the quieter, more lyrical poems. We talk of the early experimental readings by San Francisco poets, Kenneth Rexroth, Kenneth Patchen and Jack Spicer, undertaken to jazz accompaniment, and Allen says how ungracious and ungenerous those same poets were, how catty, cranky and cantankerous they were about other poets. Rexroth, in particular, turned on so many of his friends, including ultimately Gary Snyder who was “the apple of his eye.” Their falling out had occurred because Gary Snyder was appointed to some California cultural post and had generously, respectfully phoned Rexroth to offer him a grant. Rexroth had roared “You’ve sold out! I never want to talk to you again!” Then he had hung up. To Rexroth, Allen says, accepting any form of state employment or support meant selling out. I ask if Snyder and Rexroth were reconciled before Rexroth’s death. Allen thinks they were not.

He goes on to speak of his own relationship with Rexroth. Once when drunk at Rexroth’s apartment, in a moment of unwarranted indiscretion and youthful arrogance, Allen had said to his host: “I’m a better poet than you are, Rexroth.” The next morning, mortified and remorseful, Allen had phoned to apologize but he had gotten the I-don’t-ever-want-to-talk to you treatment. Rexroth had subsequently written a piece in which he expressed that in his estimation Ginsberg was “written out.” And this had been before the publication of Kaddish. Allen thought that cultivating such spite and rancour was wrong. “A Boddhisatva should not act in this manner,” Allen said, “should not aim for the heart, should not close off all chance of reconciliation.” Rexroth had turned on Philip Whalen, too, and Jack Kerouac. After Kerouac had gotten drunk while visiting Rexroth and had supposedly frightened Rexroth’s daughter – “I was there, he didn’t do it” – Rexroth had written a vicious review of Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues. In fact, Rexroth had compared the Beats to hoodlums, writing something to the effect that to come up against their work was like “going into a candy store for a pack of cigarettes and meeting a pack of juvenile delinquents.” What had aroused Rexroth’s unrelenting animosity, Allen said, was Robert Creeley’s having an affair with Rexroth’s wife, Martha, who was much younger than her husband. This had caused Rexroth to sour on the whole group. And he had never thereafter relinquished his vindictive attitude toward them. Allen recalled how many years later, he had called on Rexroth, bringing with him his aged father, Louis Ginsberg. To Allen’s relief, Rexroth had received them, but in the course of their polite conversation had cruelly asked Louis “how does it feel to have a son who’s a better poet than you are?” This was petty, pointed revenge, Allen said, clearly directed at himself, but inflicted on an innocent bystander. Louis had replied: “It feels marvellous.”

Peter emerges from his eye test together with the optometrist who is grinning broadly and good naturedly at this unusual customer who seemingly has entertained him. While we wait for the prescription to be filled, Allen goes over their budget with Peter, producing from his pocket a detailed list of expenditures, discussing with him each item and outlay, including cab fare and new glasses, noting how much each owes to whom. Peter patently ignores him. “Don’t you want to hear the information, Peter?“ Ginsberg asks him. “Oh yes yes yes yes. Oh yes yes yes yes yes yes,” Peter replies. “Mmmmm. Mmmmmm,” he adds. Both men light cigarettes. Allen says that he just started smoking cigarettes once again in Amsterdam after smoking some hash there. (Smoking hash in the European-style, that is mixed with ample amounts of tobacco.) He explains that they are on a tight budget, that’s why they try to stay in the homes of local acquaintances or adherents rather than paying for hotels. Here in Copenhagen a woman named Lotte Thomsen has generously invited them to stay with her in her apartment, Allen says. “On the whore street,” Peter adds. (Lotte Thomsen’s apartment is located on Teglgaardstræde a short side street where aged, gray-haired, grandmotherly prostitutes display themselves in street-level windows.)

It is decided that we should have lunch. I offer to pay but they won’t hear of it. “We have money,” Allen says, “we’re just cheap.” Peter walks the winter sidewalks of the city in a stiff-legged hunch, blowing kisses to onlookers in bus windows, stopping to talk to an old lady, muttering “oh yes yes yes yes yes yes.” I translate menus posted on the windows of cafés and restaurants and eventually we settle on a Chinese restaurant. During the meal, Peter eats voraciously, smacking, slurping, groaning, humming. At one point Allen tries to restrain him from eating more than his share. Peter lifts his plate from the table, and shovels the food piled on it into his mouth. When his plate is empty he raises it to his mouth with both hands and licks it clean with grunts of pleasure, then takes possession of the leftover rice, dowses it liberally with hot sauce and spoons it down, muttering “ummmm, ummmmm, very good, very good, very good.” Allen regards him with a mixture of amused disapproval and fond indulgence, rather as a forbearing parent might regard a mischievous child.

As we eat our lunch, Allen asks me if I have read Tom Clark’s Poetry Wars. (The Great Naropa Poetry Wars, published in 1980 recounts an incident that occurred during a Buddhist retreat under the direction of Ginsberg’s guru, Chogyam Trungpa, where at the command of Trungpa the poets W.S. Merwin and Dana Naone were seized in their rooms and forcibly and publicly stripped of their clothing.) Yes, I have read the book, I say. Allen says that although he was himself not present at the now notorious retreat, he has spoken with many who were present and has concluded that Tom Clark’s account of the incident is “unrecognizably distorted.” Clark, he says, has shown himself to be more than spiteful in this matter, indeed, “paranoid, psychotic.” In Clark’s book, Allen says, his statements regarding the parties concerned in the incident are quoted out of context. He had, in fact, said a number of good things about Merwin as a person and a poet, but Clark had perversely chosen to print only the negative remarks he had made. It was, of course, true that he had said that he would rather read Trunpa’s poems than Merwin’s. Indeed, he still finds Trungpa’s poems “more interesting” than those of Merwin. But Clark’s depiction of Trungpa surrounded by armed bodyguards was nothing more than “a paranoid fantasy.” The misrepresentations disseminated by Clark had been harmful for the Naropa Institute which had found itself accused of “Buddhist fascism.” And for attempting to defend Trungpa, Allen himself had been labelled a “Stalinist.”

My offer to accompany Peter to the hospital while Steven and Allen go the National Gallery is accepted. In the emergency room I translate information to the desk nurse and then sit waiting with Peter. I ask him if the cut on his foot hurts him. “No,” he says, “it feels good. Pain is good medicine. It clears consciousness.” He says that with practice, through meditation, you can learn to isolate the pain and diminish it, perceiving it as only a small part of your whole body and a small part of your total consciousness. From his trouser pocket he draws forth a book that he recommends to me. It is The Life and Teaching of Naropa by Herbert V. Guenther, published by Oxford University Press, 1963. I ask Peter if he still plays the banjo. He did until recently, he says, but in Amsterdam he got so angry that he smashed his banjo to pieces. He got angry at President Reagan. “Reagan wants to kill everybody,” Peter says. Peter’s foot is treated and he is given a tetanus booster. We rendezvous with the others at the National Gallery.

Allen is primarily interested in seeing the work of the Danish painter Nicolai Abildgaard (1743 – 1809). He has recently seen and admired some of Abildgaard’s paintings in the city of Aarhus after giving a reading there. Allen says he is intrigued by the connection between Abildgaard and Henry Fuseli and through Fuseli to William Blake. Peter and Steven are now feeling tired and return to Lotte Thomsen’s apartment for a nap. Allen and I view the museum’s collection of Abildgaard paintings. I translate titles. Allen is unhurried, focused, engaged and attentive in regarding the paintings, amused by Abildgaard’s allegorical painting “The Cultural History of Europe,” in which the figure representing Culture sleeps while fierce battles rage all about. Abildgaard’s canvases depicting Philoctetes, Anakreon, Sappho, and Ossian also draw his admiration. Another Danish painter singled out for praise by Ginsberg is L.A. Ring (1854 – 1933). We pause before his melancholy painting titled ”In the Churchyard of Fløng,” which depicts an old woman with wrinkled countenance and faded blue eyes sitting with hands folded on her lap before a grave in a country churchyard. The dates of birth and death inscribed on the cross at which she stares indicate that the grave is that of her late husband. She sits beneath a leafless winter tree. The churchyard is set among barren fields. Far in the distance can be discerned the steeples of a church. Allen comments upon her facial expression, the grief, the desolation and despair, the utter lack of hope and illusion. She is thinking, he says, back to her girlhood and the notions of life she held then and she is thinking forward to her own death. Life is not what she once thought it to be, he observes, life is death and it has always been so even when as a girl she thought otherwise. The church so small and insignificant in the misty distance can offer her no comfort or consolation. She is alone, he says, with her stark awareness of “the enormity and finality of death.”

Allen is elated by the Emil Nolde paintings and delighted by the Rembrandts. He studies closely a Rembrandt portrait of an old lady and remarks upon the profound sorrow and disillusion expressed in her woebegone face, comparing it to that of the woman depicted in the painting by L.A. Ring. Discovering the museum’s collection of paintings by Peter Bruegel the Elder, Ginsberg gasps with “oh” and “ah.” He is particularly taken by the large Bruegel painting of “Christ Driving the Traders from the Temple,” which he examines closely and at length. He remarks to me that “Bruegel is like Shakespeare in his poetic composition.” Allen points to details in the painting, arguing that not only the money changers but nearly everyone in the crowd around the temple is engaged in some form of grasping greed, including the beggars, a thief, a quack doctor, and the many merchants and farmers who have come to buy or sell animal stock. And in the lower right-hand corner of the painting there is a half-naked child aged about four years, facing out from the canvas with a look of terror in his eyes, innocent witness to this appalling human spectacle. (I think of Peter.)

We view paintings by Mantegna, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Titian, Rubens and others, discussing artists and paintings referred to in Pound’s Cantos, then retire to the basement canteen for coffee. Allen tells me that he is contemplating writing an epic poem based upon a dream he had the previous night. In the dream, Allen recounts, he passes through a tunnel into a magic castle. This is a domain where wishes are fulfilled but where guru-tricks are also played upon those who enter. Here, he encounters a beautiful naked black man who asks him: “do you want me?” “Yes!” Allen replies avidly. “Look here,” the black man says, indicating a diseased portion of his chest. “How are your other parts, your limbs?” Allen asks and is shown other disfigured and unwholesome areas of the man’s otherwise alluring body. Later, a young boy offers himself to Allen but suddenly vanishes. There the dream ended. Allen compares it to Keats’ poem, “Christabel,” which relates the encounter between Christabel and a mysterious, beguiling figure named Geraldine whose body is ultimately revealed as bearing some terrible disfigurement that mars “her bosom and half her side.” Allen also compares the dream to the “Magic Theatre” section in Herman Hesse’s novel, Steppenwolf. The “Magic Theatre” is a realm where fantasies – including erotic fantasies – can be lived out and where spiritual or psychological instruction takes place. The dream, Allen says, has lingered in his mind and absorbed his attention all day. Perhaps he can use it as the basis for a new poem, but he mustn’t strive, he says, striving would create an anxiety that could drive away the meaning and inspiration offered by the dream. He adds that dreams have served him in other ways at other times. He has even composed lyrics in dreams. The first stanza and general outline of “Guru Blues,” for example, were conceived in a dream.

Outside, early winter darkness has fallen. We take a bus through the city to the editorial offices of Politiken, a Danish newspaper that has promised him payment for an interview he gave to a reporter on the night of his arrival in Copenhagen. Unfortunately, it proves that the payment cannot yet be made to him, so Allen leaves a forwarding address where he will be staying while in Sweden. He is clearly disappointed, even becoming testy with the young man at the reception desk. We walk the raw, evening streets of Copenhagen to Teglgaardstræde where Allen and Peter and Steven will be sleeping one last night before leaving tomorrow morning for Sweden. In the light of the antique street lamps, his face looks drawn and weary. He seems a sad man. I think that the discourses he delivered on the sorrowful, disillusioned faces of the old women in the paintings at the National Gallery were, in part, projections of his own current state of spirit. The preoccupation with his father’s death and with “Father Death” in his recent poems and songs would seem to bear this out. And there would seem to be but little consolation to be drawn from the rather bleak Buddhism he embraces.

We ascend the wooden stairs of the old building where he is staying, walk a dim hallway, and enter an apartment with half-timbered walls. Peter is asleep. I shake hands and say goodbye to Steven and ask him to say goodbye for me to Peter. I shake hands with Allen who thanks me and says: “Well, we saw some Bruegels and Rembrandts together.” We speak our final farewells and I descend the stairs into the dark, windy street. I leave them there to their lives in which this has been but one day, Allen and Peter, two ageing heart-friends whose fates and souls are so interwoven, both seeking salvation, both struggling still with vanity and anger, both alone, both far from home this winter night.

— Gregory Stephenson

Leave a Reply