Mahmood Karimi Hakak is a poet, author, and translator. In addition, he is a theater and film artist whose creative and scholarly works are focused on peacebuilding through the arts. He is the founder and CEO of Café Dialogue LLC, and Founder and President of Free Culture Invisible LLC. He has created over seventy stage and screen productions in the U.S., Europe, and his native Iran. His creative works explore the ideas of intercultural discourse and reconciliation.

His 1979 production of Passion of Ashura aimed at alarming his country against a rushed revolution, where one dictator might replace another. In 1991, he created Seven Stages: A Symphony in Seven Movements as a dialogue between the 20th century’s most celebrated Iranian female poet Forough Farrokhzad, and 12th century Sufi poet Jalal-al-Din Rumi. His selection from Rumi’s Masnavi (2000) employed actors from seven different nationalities, each speaking in their native tongue. In his 2001 adaptation Six Characters in Search of An Author, Pirandello’s characters appear through the ruins of The World Trade Center where the murderers and the murdered faced each other. In 2008, Karimi Hakak used Aeschylus’ The Persians to reference the devastating aftermath of American military industrial expansionism. His HamletIRAN (2011) imagines Shakespeare’s prince within the Iranian Green Movement of 2009.

Karimi Hakak has published seven plays, two books of poetry, five translations from and into Persian, and numerous articles and interviews in both Persian and English. His translation of Hafez (with Bill Wolak), entitled Your Lover’s Beloved: 51 Ghazals by Hafez (Cross-Cultural Communication, 2009) was nominated for the Best Translation of Poetry by American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) in 2010. He is a recipient of several artistic and scholarly awards, including Critic’s Choice (1999), ACTF Merit Awards for Best Direction (2003, 2008, and 2011), and the 2005 Raymond Kennedy Excellence in Scholarship Award. In 2009, Karimi-Hakak received a year-long Fulbright award to produce an original theater production with Palestinian and Israeli actors. However, facing the difficulties of staging such a play within the region, he created The Glass Wall, a documentary film where theater practitioners of both sides express their frustration and opposition to the barrier that has divided them physically, intellectually, and artistically. Professor Karimi-Hakak has taught at CCNY, Rutgers, Towson, and Southern Methodist University in the U.S., as well as universities in Europe and Iran. Presently, he serves as Professor of Creative Arts at Siena College in upstate New York.

BW: In 1991, you directed a play entitled Seven Stages. Tell me a little bit about that play.

MKH: Seven Stages sprung out of the curiosity of a few American students about Iranian culture and poetry. I was teaching at Towson University at the time, and the year before I had directed The Epic of Gilgamesh, the first staged adaptation of the entire poem in the U.S. That production, created through improvisations and experimentation emerging from physical expression of a poetic text, was invited to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. However, the large cast and expansive scenery made it difficult to travel. So, I was asked if I could create another more manageable play in the same style. I agreed, even though I had nothing in mind at the time.

BW: So, you made a play about Rumi and Forough? They are over eight centuries apart. How did you make the connection?

MKH: I didn’t intend on making a play about them. The play made itself! Let me explain. As a habit, I often recite Persian poetry out loud, especially when I am happy, depressed, frightened, or baffled. The lines I speak are from Rumi, Hafez, Forough, Shamlou, Sohrab, and others. I do this almost unconsciously, when I am in class, in my office, in the school cafeteria, in parties, wherever. And, being surrounded mostly by students, colleagues, and friends, I sometimes have to translate lines I speak.

Anyway, it was in a middle of a party, I think, that I recited a poem by Forough Farrokhzad for a young friend explaining how she wrote this poem in style of Rumi’s Masnavi. My friend commented that, “Maybe she is trying to have a dialogue with Rumi.” That night she and I spent the entire evening flipping through these two poets; works. By the next day, I knew what I would take to Edinburgh.

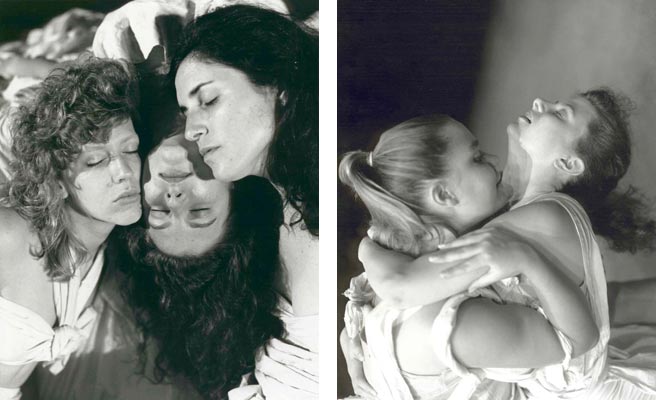

I invited seven graduating students to join me. The more we delved into their works, the more we agreed that they are indeed speaking to each other, and to us. Towson’s theatre studios were booked all through the day. So, we decided to rehearse late, very late, often starting at 10 p.m. and going on till we dropped. Seven weeks later, we had a play, Seven Stages: A Symphony in Seven Movements. It developed as a dialogue between Rumi and Forough and my young friends. The production ran for two weeks at Baltimore’s infamous Theater Projects, before it traveled to Edinburgh, where it was acclaimed by the critics.

BW: Was that the first time that you used naked actors on the stage?

MKH: I have always been interested in and intrigued by the purest form of bodily expression in a theatrical presentation. In late 70s as a graduate student at Rutgers, I created a play based on Forough Farrokhzad’s “Earthly Gospels,” called Me & My Mirror, where the main character shreds the layers of hypocrisy—the masks we all hide ourselves behind—represented by his clothes in order to pursue the truth. As an actor in Richard Schechner’s 1984 production of Prometheus, I played the title role which required me to appear naked on stage.

In that production, pondering on what we have done with his gift, Prometheus suffers painful bonds like that of a tortured political prisoner in Iran and elsewhere. In both these productions, as well as in Seven Stages, nakedness is much more than taking off one’s clothes. It is not a trick to enthrall the audience, nor is it imposed on the play or the actor. Nudity here is a process that the actor struggles through in order to shed layers of duplicity and pretense. Undressing, in other words, indicates a path by which an individual may strive to find the truth.

In Seven Stages, the character is ridding herself of worldly possessions, attempting to reach some level of purity in body and soul. It is not the actor, but the character that reaches such a stage of ecstasy where she no longer hides behind any coverings. The one who achieves that total transparency is the one whose virtue becomes a healing ground for others’ sins. And, at the play’s conclusion, it is only this character that leaves the stage unharmed, while all others are annihilated. She is the one reborn, resurrected, revitalized.

BW: In 1992, you returned to Iran to visit your mother for ten days. How did that ten-day visit end up lasting for seven years?

MKH: A Latvian theater troupe I met in Edinburgh invited me to Kiev to teach a workshop. I had already received a small grant from Towson University to visit Iran in order to make some interviews on theater topics that I was researching. So, I decided to combine the two opportunities and make a ten-day stop in Iran on my way to Kiev.

While in Iran, I was asked to give a talk in one of my ex-professor’s classes. During my lecture I, arrogantly, scolded students for being lazy in comparison to those in my generation. A brave young woman stood up and spoke. With a combination of pity, anger, and envy apparent in her voice she cried out, “You are here bragging about how hard you studied, and we do not. How much you knew when you were our age, and how much we do not know. What you fail to understand is that it was your generation that created this revolution. I was just a small child at that time. And as soon as your generation realized that this was not what you had expected, you left, leaving us to deal with the aftermath of what you had started. We did not ask for this, nor did we have the means to leave like you did. For all these years not many worthwhile books have been published. Our progressive artists and intellectuals, those who could not leave, are either dead or in jail, or as Forough wrote ‘swamps of alcohol and opium have dragged them down to their depths.’ We are being taught by those who, in most cases, are chosen not because of their knowledge in the field but because of their loyalty to a certain ideology, or so they pretend. What many of us struggle with is trying not to sell our bodies to pay for our tuition. I cannot believe that you have the nerve to come here and chastise us!” Adding with a sigh, “And then of course you will leave too.”

Her words pierced my heart. I sat down and cried. She cried too. The entire class cried. What she said transformed my decision about leaving Iran. I promised her, the other students, my ex-professor, and myself, that I would stay.

BW: What did you do in Tehran during those seven years? Were you allowed to work as a theater director?

MKH: Well, at first it looked like I could work. I was invited to have lunch with some theater authorities and was promised all kinds of assistance and cooperation. But soon I learned that I, too, would be expected to prove my loyalty before I received any help. I was asked to write an article or have an interview where I declare that Western theater is sinful and corrupt, or theater is purer, healthier, and more artistically viable with present administration. Obviously, I couldn’t say that. So, I was politely asked to submit production proposals and await their approval. Well, I did propose. And I did wait. Months after months and years after years, my proposals faced a wall of silence. Meanwhile, I met and taught many young artists and students who threw their emotional support behind me, constantly encouraging me to keep the proposals going, even if there was no response from the authorities. Finally, in 1998, when Mr. Khatami won the presidency, my 125th proposal was approved, and I began working on Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

BW: After years of effort, finally you were granted permission to produce and direct Shakespeare’s comedy A Midsummer’s Night Dream. Can you describe some of the constraints that the censors imposed on you and your actors in order to allow such a play to be produced? In other words, what did you have to agree to in order for the production to be approved?

MKH: As you can imagine, this is a long story, but I’ll try to offer a condensed version. As I mentioned, while my proposals were left unanswered, many young actors and students criticized theatrical authorities by publishing articles and interviews with me where they would ask about the fate of my latest proposal, and whether I have received a response, thus keeping the matter alive.

When Mr. Khatami was elected President in 1998, I was called into the Center for Performing Arts’ office, where performance permissions are issued. There I was told in so many words that “now is the time to propose a play for production.” I refused to write another proposal, sighting the previous ones asking them to “chose any of the plays I have proposed before, or even another from theater history canon that you like, and I will direct it.” After a brief exchange, the new official presenting himself in opposition to the ones who occupied that office before, suggested Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream “because this is a comedy with no relevance to present day Iran,” he said, “so suspicious minds searching for a ‘footstep of sin’ cannot find anything to object to.” I happily accepted the suggestion, especially since I had staged this play ten years earlier in the U.S. and was well familiar with it. However, that also proved not to be smooth sailing, and I faced a variety of kinds of resistance and obstacles in casting, rehearsals, and performance from the very first day.

BW: Can you cite some examples of the kinds of obstacles that you faced?

MKH: To begin with, I was promised a reasonable budget (all plays were produced by the government those days) and signed a contract, but the money was never released. Nor were we assigned a rehearsal space. So, again with the support of my young friends, we chipped in from our own pockets and rehearsed in my mother’s living room, an open space about 250 square feet. Then, there was the constant flow of “inspectors” sent by the Center of Performing Arts with constant suggestions about how to improve the text that ranged from very silly and to stupid.

Here is an example: An “inspector,” bragging that he held an MA in theater, suggested that in order to avoid un-Islamic relationship between man and woman, I should have Lysander and Hermia marry each other before they escape into the woods! Imagine! The entire play happens because these two young lovers are not allowed to marry each other. That is why they run into the woods to escape to where “the sharp Athenian law / Cannot pursue” them. Another censor objected to the proximity of a male and female characters on stage. “From where I am sitting” he said, “they seemed to touch each other!” I pointed out to him that, “You can actually see that there’s a distance of over three feet between these two actors, and that they did not touch.” He responded, “Yes, ‘I’ know they did not touch. But some people in the audience may think they touched.” There was no use explaining to this gentleman that theater is the art of make-believe, so I moved the two actors farther apart from one another.

BW: How was the production received?

MKH: It was completely sold out during the 1999 Tehran Fajr Theater Festival, where it received the Critic’s Choice Award. Following the festival, a permission was issued for 45 public presentations of the play. However, the troubles did not stop.

The first night, the theater’s doors were unlocked only a half hour before the curtain, leaving 35 actors and support staff only 30 minutes to change into their costumes, put on make-up, and check the lighting and sound. The audience who had gathered at the doors over an hour before show time, were told that the play was canceled due to technical difficulties. But they did not believe this and waited patiently. Actors hurriedly warmed up, technicians rushed through the cues, and the play opened as scheduled to a cheering sold-out house.

The second night, the box office keys were mysteriously lost, and no one could buy tickets or pick up the ones reserved. Again, the audience, by now used to these games, waited in the freezing February Tehran weather for almost an hour, when our brave house manager (one of those who had supported my cause all throughout the production) opened the theater doors letting all in regardless of who had tickets and who did not. Finally, on its third night some thugs from the Revolutionary Guard raided our production disrupting the performance, cursing the actors, the audience and me, and then they closed the production.

BW: When you returned to New York City in 2000, you immediately staged The Masnavi of Rumi at La MaMa. Tell me a little bit about that production and how it differed from your experiences as a director in Iran.

MKH: Well, to begin with, there was no theater authority to impose censorship on this production! I had just returned from seven years of living in a place where most my energy was spent fighting the existing absurdities, not only artistically, but socially, politically, intellectually, even emotionally. Working at La MaMa, I felt like an old bird that has been let out of its cage for the first time. There was no stopping me. I was running everywhere creatively. I was back continuing to further experiment with Ascetic Theater, a technique of staging plays I practiced during the years before going to Iran. I wanted the text to reach the audience beyond words and language. And what better text than that of Rumi to do this with?

So, I chose seven stories from the Masnavi as basis for the text, designed the stage as a canopy placed on seven columns, each with calligraphed poem by Rumi in a different language. The actors came from seven different countries of origin, and seven languages were spoken on stage. It was as if I wanted to shout messages of peace and love ingrained in the Masnavi so all people would hear it and understand it regardless of their cultural or linguistic background. And the production worked. The play communicated to people of all social, cultural, and political backgrounds. This play’s success not only rejuvenated my spirit, it also provided a much-needed positive page on my resume (something that was lacking for the seven years I struggled in Iran) which helped in obtaining a respectable job. I was hired to teach and head the Directing Program at Southern Methodist University the next year.

BW: So, you were in Texas when 9/11 happened. What plays did you stage in Texas?

MKH: I was asked and accepted to direct Six Characters in Search of an Author. We were in rehearsal when 9/11 happened. I immediately adjusted my concept having the characters appear through the ruins of World Trade Center. The interaction between Pirandello’s incomplete characters and the acting troupe, resembled a dialogue between the spirit of attackers and the attached under tons of steel and concrete in ground zero.

The production touched the theater critic for Dallas Morning News so deeply that he ended his review with, “I wept for terror and joy all through the final half of this production. I wept walking back to my car. I wept all the way home.”

BW: Yet, you left SMU and began your tenure in the Creative Arts Department of Siena College in upstate NY. Why? And how has your experience been at Siena?

MKH: Remember, theatre is a collaborative art, and theatre workers, especially in an educational setting, must function as a family. Unfortunately, SMU’s theatre program, at that time, resembled a dysfunctional family filled with resentment and envy, making it an unhealthy environment, especially for the students. So, I looked for other alternatives, and when Siena offered the position, I accepted it.

From the very beginning, Siena College provided the kind of big-hearted small family that I felt I might want my own children to grow up in. I moved to Siena in the Fall 2002, not only because of collaborative colleagues, and supportive administration, but also because of its geographic location. It is less than three hours’ drive from, NYC, Boston, and Montreal, three cultural centers I wanted to be close to.

BW: How many theater productions have you directed at Siena?

MKH: I have directed over fifteen productions, both within the college and outside. Almost half of these productions were original plays or new adaptations of existing plays. Included in this are; Iphigenia, written by Michael Sham, using the premise of Euripides’s Iphigenia At Aulis to comment on the senseless Iraq war; a new adaptation of Chekov’s The Seagull, staged within a decaying modern city, where humanity is destroyed and ethical values damaged; Paydaayesh: A Creation Story, based on 5000 years old Persian creation stories; a new adaptation of Aeschylus’ The Persians; staged to expose the futility of America expansionism; and HamletIRAN where Shakespeare’s characters were placed within the Iranian Green Movement of 2009.

In 2007, we invited an Israeli playwright, along with three American artists, to develop Benedictus: An Iran, Israel, U.S. Collaboration Project with Siena students. This play was later staged at number of professional theaters across the country, and also participated in the 2007 LATC World Theater Festival, where it was awarded as the Critic’s Pick.

BW: In 2012 you founded Free Culture Invisible (FCI) in order to present the lesser seen films from the Middle East and North Africa to the international audiences. Why did you move from directing theater to promoting cinema?

MKH: Working on films is not a new thing for me. In 1994, when I wasn’t allowed to do theater in Iran, I produced a feature film entitled Common Plight. The fate of that film was not unsimilar to that of the theater proposals. This time my pocket was the aim of attacks! While the government approved the script, I was not allowed to direct it, so I agreed to produce the film, but, unlike any other film in those days, we were given no budgetary assistance. Thus, Common Plight became the first film after the Islamic Revolution that was produced entirely with personal funds.

This film was also the very first Iranian film in which a new position was created, bazigardan, a member of directorial staff whose job it is to work directly with actors. Something similar to what is called an acting coach in the West. This title has been used in almost every Iranian production ever since. However, to discourage me from attempting another film, they pulled this film off the screen one day after it was released.

Anyway, back to why I founded FCI. Once I settled in the U.S. again, I received a number of films, shorts, documentaries and features from my friends and students in Iran. These were films that, like Common Plight, for variety of reasons their screenings proved difficult if not impossible. So, I took it upon myself to show them to larger audiences within universities, community centers, and actual movie theaters. Soon, the numbers grew and so did the interest.

In 2012, I founded Festival Cinema Invisible, an LLC dedicated to screening only Iranian unseen films. Soon the news traveled, and I was bombarded with films from other parts of the Middle East and North Africa. This was followed by receiving photographs, paintings, and poems that had suffered a similar fate in the countries of production. Thus, Festival Cinema Invisible expanded to include other forms of arts and literature created by MENA artists, both inside the region and in diaspora, and we changed the name to Free Culture Invisible. As you can imagine, such undertaking cannot be managed without the support of other interested individuals, and I am thankful, honored and pleased to say that now FCI receives assistance from a dozen individuals who volunteer their time and talent to introduce these artists’ works to the world.

BW: : How can cinema be invisible? That’s a contradiction. What do you mean to convey by the title Cinema Invisible?

MKH: This is a very important question and requires special attention which is beyond the limits of this short interview. So, to provide a more comprehensive response let me refer you to the FCI website where you will see an extensive definition about the Invisible Cinema.

BW: Tell me about the 7th and latest Festival Cinema Invisible.

MKH: The FCI 2019 offered a selection of the best of the past six festivals. Over fifty films were screened in seven categories: Experiments Invisible, Artists Invisible, Rights Invisible, Humanity Invisible, Women Invisible, War Invisible, and Life Invisible. These films are all made by MENA filmmakers living inside the region or in the diaspora. They ranged in length from two minutes to 55 minutes, and represent the works of artists from Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran, Morocco, Israel, Lebanon, Qatar, Kurdistan, Poland, Belgium, and the U.S. A complete list of 2019 films, as well as details on each films, interviews with filmmakers, and critic’s comments is available at FreeCultureInvisible.com.

BW: Any final words?

MKH: I would also like to thank my colleagues at Free Culture Invisible, especially our Executive Director, Dr. Roja Ebrahimi, without whose tireless work we could not have opened this window to the life, people, and culture of a part of our world that many others know very little about.

At this juncture, we live in a very dark time when the survival of humanity itself is in question, a time when certain ideologues do all they can to heighten the existing tension by creating frictions between us as intellectuals, activists, artists, and just simple human beings. They divide us so that they can conquer us.

But, it is up to us, the people, not to allow the destruction of our values, our ethics, and our principles by practicing respect, tolerance, and understanding. Furthermore, it is our firm belief that the arts can play a pivotal role in this undertaking. Therefore, in the future, we hope to be able to better serve our communities by building stronger bridges, by fostering intercultural dialogue, by involving more people in our collaborative projects on line, and thereby, through the arts, helping everyone appreciate more fully and more deeply the gifts of life and freedom.

Leave a Reply