Here are all of the installments:

Part I · Part II · Part III · Part IV · Part V · Part VI

8. Homeless Newsreel

(Charcoal Wool)

Reader Road Map: homeless, 2012-2014.

There isn’t any privacy in the bathrooms at Butler Library. I use dispenser soap. Each day, a labour to stay clean. I wash my hair in a sink at lightning speed. I dry my bangs with an electric hand-drier mounted against a wall.

I wear the same black skirt every day. Long, to the floor. It is a pretty skirt. Embroidered. It has a built-in petticoat. I wear combat boots and socks. I rinse my socks in a bathroom and place them across a hot radiator in an empty classroom to dry while I read.

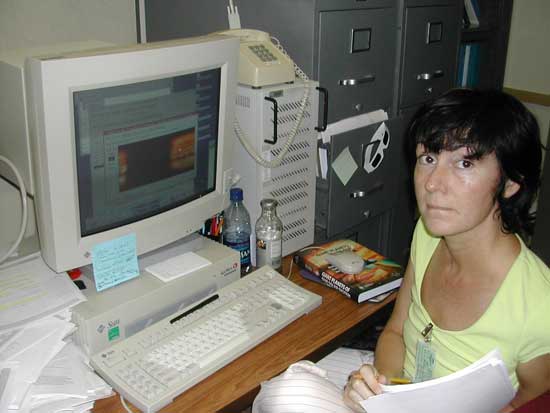

I weaken from sleep deprivation during the second year of homelessness, but I continue writing my memoir. A female administrator begins to take my few clothes home with her once a week to wash and dry. (Most of my clothes are stored at Columbia under lock and key, including my Alice Blue Gown bridal dress.) “Give them to me,” she says. Her husband dies and she gives me his wool walking coat, charcoal in colour.

Before my homeless spree, I often gave both her and her husband presents, including paintings. She witnessed the anvil hammer of age discrimination doled out by Columbia’s faculty while I was a student (“She is too old,” they’d told her when I applied for a student job. Instead of working in her department over summer break, I’d applied and gone to Caltech’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship program, working on Jupiter data).

She tells me a student once sued Columbia for age discrimination (and won), but I never sued Columbia. I didn’t sue Jake Seuss for breach of contract over our marriage, either. Nor did I sue the many (famous and powerful) men who sexually harassed me. I guess I’m not the suing kind: That is for disgruntled hearts?

My heart belongs blissfully to Samish (Jake Seuss). I hope to inspire courage.

9. New York City

(Cranberry Juice)

Reader Road Map: picks up in late 1980’s. News Topic: the sinister death bell of HIV/AIDS.

“I remember we used to speak, even after one or both of us had gone home,” said Samish (Jake Seuss), talking about Jack Kerouac School. “And you were going to Rome or somewhere that seemed very Grand Tour or Daisy Miller to me at the time.” (He wrote to me in an email when we were first engaged).

The first thing I had done on my return from Rome to the States was search out Jake Seuss at his mother’s house, using a telephone number he’d given me at Naropa.

“Hello,” his mother said before Jake Seuss took the phone. He said he hadn’t been well and lived in Virginia.

“I’m going bald and wearing polyester.”

“You’re teasing!” I rejoiced at the sound of his voice. A voice I’d not heard for over four years. I did not care if he lost every hair on his body and wore sackcloth. He was still the boy for me, but I couldn’t visit Jake Seuss in Virginia; I was off to conquer Manhattan via North Carolina, where I was enrolling at a dance and drama conservatory. And I was so very young. Sam Jake Seuss was thirty. We were at a different junctures in life.

An opportunity arose to intern for a theatrical production bound for Broadway: Kafka’s Metamorphosis starring Russian ballet dancer Mikhail (Misha) Baryshnikov with pre-Broadway performances to be held at Duke University. I helped paint the set.

Steven Berkoff was the play’s director. In the final few days of rehearsal, Berkoff said to change the multicolored set to a stark grey and paint black stripes onto the stage. We worked all night to create Berkoff’s new vision.

Choreography called for Baryshnikov to move gymnastically inside an open-grilled cage placed center stage, doing physical feats while making loud insect noises. Baryshnikov was forty years old and still dancing professionally; Metamorphosis was his initial stab at acting. He was already a world-renown heart-throb. (Later, he’d star in the television series, Sex and the City with Sarah Jessica Parker, who’d attended the same NC conservatory, but a few years ahead of me. I never met her, but I did meet at drama school another alumnus, the boy who eventually wrote What’s Eating Gilbert Grape—a movie that launched the careers of Johnny Depp and Leonardo DiCaprio.)

The stage lights cast heavy shadows: Berkoff’s Metamorphosis opened with actors walking onto stage in mime, executing a slow-motion jump rope sequence, without any ropes. Actors’ costumes were purposefully drab.

Misha Baryshnikov was fabulous. He pretended to drink milk from a bowl like a cockroach, clicking his tongue. Strongly muscled, he climbed the bars of his cage. The ladies in the show swooned over him. A female lead twisted her ankle during rehearsal and he swept her into his arms, offering to bring her an ice cream.

On the eve of opening night, a big snowstorm hit North Carolina’s Duke University campus. We all had rooms at the same hotel, including me, the show’s intern.

Downstairs at the hotel bar, having dinner, Baryshnikov ordered a Cobb salad and a cranberry juice with soda. Disciplined and serious, he drank no alcohol. He gripped the back of a chair, doing leg stretches, waiting for dinner. He said he needed to keep moving to quell muscle pain; he’d sustained a lot of injuries as a dancer.

The design and production crew for Metamorphosis liked to joke. Women adored Baryshnikov, making the crewing guys jealous. They talked among themselves about putting a whoopee cushion inside the set’s cage, but nobody dared do anything mean to Baryshnikov.

At this time in American history, AIDS devoured artists. Tensions ran high: everyone in the cast knew someone who had died or was in the process of dying. The brother of someone closely associated with the show received an AIDS diagnosis during our final rehearsals. He’d been attacked in Washington, DC and contracted HIV. The Big Bad Wolf was sifting Little Red Riding Hoods, left and right.

An actor from Dynasty lounged before the hotel’s central fireplace after dinner: Jack Coleman (Steven Carrington on the popular TV show). Patrick Fitzgerald, later on Broadway in Wendy Wasserstein’s (Bruce Wasserstein’s sister) The Sisters Rosensweig, sat near the fire reading plays during North Carolina’s snowstorm.

News reports chilled America colder than a communism scare: “AIDS cripples the body’s immune system…Victims left vulnerable to cancer and fatal infections…Caused by a virus believed to be passed through blood and semen…Disease largely confined to homosexual men and abusers of injected drugs.” Everybody was terrified. In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, AIDS was a death sentence. People talked about the disease nervously.

Snow fell heavily, cocooning our hotel like a chrysalis.

Berkoff asked me to accompany him upstairs and I stepped proudly into an elevator. When I declined his sudden sexual invitation, the elevator stopped. I returned to the dining room, Berkoff proceeding to an upper floor angry.

People tried to let off steam and relax: the crew by making jokes about Baryshnikov and Berkoff, by trying to seduce a pretty intern. “A slip of a girl,” the show’s manager called me.

After the elevator incident, Berkoff tried to push me out of my internship. At the last dress rehearsal, an actor asked me to prompt their lines because that actor’s understudy wasn’t available. I knew well the role. Steven Berkoff flew into a fit. From his seat, he turned to face me for the first time since the elevator incident. Shouting so that everyone could hear, even from the back wings of the stage: “What! Are you going to be the understudy now?”

I had helped with everything from hanging lights, to painting the stage, plaiting the actress’s wigs, and now, yes, I would act as understudy. My hair in high ponytails, I stood, shaking like a leaf. The theatre silent, I was about to cry.

Misha stepped out from backstage.

It was a part of the show before he was supposed to walk on and say his lines. It wasn’t yet time for him to appear. Into the light, he stepped. Baryshnikov didn’t say a word. He just stood in spotlight: Mikhail Baryshnikov, ballet superstar. He looked like Michelangelo’s statue of David.

Berkoff shut up and on went the show.

The production was a success, largely due to Berkoff’s genius. Everybody came for opening night in New York at the Barrymore Theatre, including David Bowie, Nancy Reagan, Katherine Hepburn, Natasha Richardson, and Helena Bonham-Carter.

“Thank you for a fascinating and illuminating night at the theatre,” Hepburn said to the cast, drawing out the words in her distinctive voice. Baryshnikov received a Tony nomination and, in my opinion, he should have won.

I worked at all sorts of jobs in my lifetime; it’s rare when artists earn a living wage, but I relished the unpaid Metamorphosis internship. I shed tears when it was time to leave. Baryshnikov made a point of saying loudly to another actor within my hearing, “What a sweet girl.” I never saw him again.

My first experience with New York City was Metamorphosis. I based myself MetamorphosisManhattan for the next thirty years, intermittently bouncing around the States and back to Rome. After Metamorphosis opened, I painted a mural depicting Marilyn Monroe in North Carolina where the owner of Pepper’s Pizza in a college town hired me. Instead of the long gowns I’d worn at JKS and in the cloister, I wore a torpedo-thrust bustier and a black miniskirt with little bows up the back.

I painted Marilyn supine, swathed in mint green bed linens, otherwise naked, cracking an egg yolk into a glass on a breakfast tray.

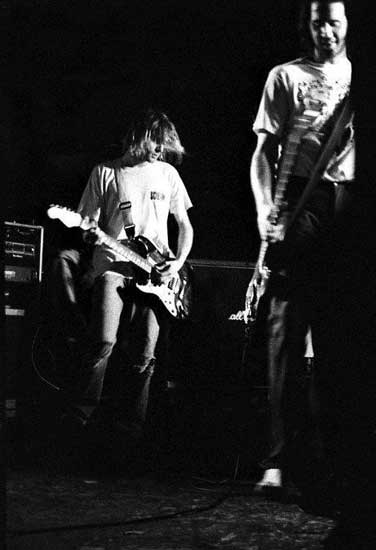

Down the street from Pepper’s Pizza was Schoolkids Records. The independent music sector was set to roar with the success of grunge bands like Soundgarden and Nirvana, though not quite yet. Nirvana band members strolled in one afternoon for a late lunch while I was painting Marilyn. Nirvana’s debut album Bleach was just released. They were in town to play at the Cat’s Cradle, a dive club that could accommodate approximately one hundred people. Before Cat’s Cradle concerts, people generally came to Pepper’s for food. The place was popular, the coolest hangout in town.

Musician Kurt Cobain walked in quietly, but Dave Grohl came in laughing and buddying around with people, having fun. Krist Novoselic, the band’s bassist was also present. Novoselic was from Compton, California. Cobain was from Washington State and Grohl was from Virginia. It was just the three of them. Handsome, even lovely. Boys of the period liked to wear a single earring and let their hair go unwashed or wash it with bar soap. Clothes, ripped and torn. We were quite a sight. Skin and bones. Young and attractive. I did not date or take drugs, but I looked like all the other creative people around me who did.

Cobain never attended college; he wrote songs about high school: “A pep assembly gone bad,” he said in an interview a little later. Then with boyish grin, repeated for emphasis, “Gone bad.” Kurt Cobain was a star of bright bohemia, only Nirvana called it grunge.

Since I’d never heard of Nirvana and wasn’t a fan, the restaurant manager asked me to wait at Nirvana’s table. As I took their order, a waiter ran up behind me, untying a row of bows at the back of my miniskirt. The bows strictly decorative, my skirt didn’t crash to my ankles.

The boy in charge of the kitchen and cash register was a local drummer. He had blond dreadlocks, tattoos, smoked cigarettes, and wore lots of bangle bracelets. His hair smelled like tea and spice. He revered Nirvana as the best band then on tour. He shot the mini-skirt jester a warning glance, and I continued taking Nirvana’s order: big pizza slices and folded, Sicilian half-moons stuffed with melted cheese. Cobain ordered only a beverage.

“Teen Spirit,” mega hit, would scream up Billboard’s chart the following year, careening Cobain into the orbit of Hendrix, The Doors, and Janis Joplin; Nirvana was as yet relatively unknown, but aesthetes highly regarded their music. Kurt Cobain had eyes like flames. Blue, shattered flames. He sat in that booth at Pepper’s, burning.

He didn’t eat because he didn’t feel well, although the kitchen staff musicians would have turned cartwheels to make him anything he wanted. About fifty people attended his Cat’s Cradle concert. Cobain played a left-handed Fender guitar. He gave everything to a very few and he liked it that way. He said establishment rock and roll sucked. He meant big, rock star bands. Like Ginsberg, Cobain wasn’t a commercial sell-out, and that’s why he’s in my memoir.

Strangely, after Jake Seuss and I had each exited the Jack Kerouac School, Cobain wrote to the Beat poets, asking to visit JKS, and the poets brushed him off. The Kerouac School missed something good, but maybe Cobain would not have fit in there after all. He was his own new era, totally separate from Beat poets. Cobain killed himself in 1994 by shotgun blast, but he never betrayed Art and he was lucky in Love; he married the lead singer of Hole, Courtney Love, and had a baby.

Madrina telephoned me in North Carolina from Rome. She was coming to America. There was a tiny monastery of Benedictine nuns in upstate New York she planned to sponsor. Would I meet her there?

I jetted up to Binghamton, New York in a narrow-aisled commuter plane. The pilot was reassuring but there was no stewardess. I waved to him, bounding down the plane’s flimsy steps wearing a short polka dot dress and into the arms of Madrina. She was eager to see how my life as an artist was evolving and if I was happy. She had grown accustomed in Rome to safeguarding my welfare.

I stayed a week with Madrina and the upstate New York nuns. Madrina and I made pasta dough together and I picked wild lavender. We drove into Manhattan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I went all over the museum with Madrina, looking at paintings. Then we drove to Connecticut to visit a Benedictine monk who was living the life of a solitary hermit like the Desert Fathers.

When we reached his hermitage, the overjoyed monk gathered lettuces for our lunch from his garden. My bowl of greens contained a writhing worm. I showed Madrina. Like Maura at Ravenna, she swapped bowls with me. It was the charitable thing to do, to graciously accept hospitality, and Madrina did not want to disappoint our host. Next we drove to visit a group of Connecticut nuns. Naturally, while there I created a disaster. I wanted to use the bathroom but the toilet overflowed, water all out into a hallway and Madrina mopped it up, not mad or anything. She was such a sweet mother. And I was a careless girl, thinking always only of my appearance, my gown, or something equally foolish. And everywhere we went in America, I had to drink milk. She wouldn’t let me drink Coke. At home in Rome at the monastery I’d always drank wine. But that was different. Wholesome. They only had commercial wines in the States and nobody really drank it anyway. They drank sodas.

Madrina was an intrepid traveler. She’d taken me all over Italy to various monasteries.

The Connecticut nuns offered us each a crocheted bookmarker in the shape of a cross. I kept mine as a memento. Tired after the excursion, we reached Binghamton late in the night. The nuns prepared a simple repast of buttery egg omelets and large slices of ripe bananas. I don’t like eggs or bananas, but that was one of the best meals I ever tasted.

Madrina and I said farewell at an airport. It was the last time I saw her alive and it broke my heart worse than Dixie. Madrina didn’t cry, but I did. Back in those days, I guess it was about 1989 or 1990, an un-ticketed person could walk with a passenger right up to a gate to say goodbye. I walked with Madrina to the very end. I can still see her rounding the last bend in the corridor and out of sight, boarding the jetliner. Her dear head shrouded in the white wool veil she always wore. She was pleased I thrived as an artist in the United States. She said I should remain a longer time, to be certain the nunnery was my irrevocable choice in life, and I went to live with actors I’d met during Metamorphosis, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

Eventually, I rented a small studio apartment at a landmark building called the Ansonia on West 72nd Street and Broadway. I selected the Ansonia because it had once been the playground of legendary ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev. The Ansonia was built as a residential hotel in 1899 featuring live dolphins in a fountain as the lobby’s centerpiece. Diaghilev was an artistic genius. He assembled the premier ballet company of his day with male dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, the Ballets Russes. In 1909, the Ballets Russes’ first performance starred Nijinsky and ballerina Anna Pavlova. The Ballets Russes was received amid an uproar of unprecedented critical acclaim, impacting the nascent style of Art Deco and influencing Fauvist painters.

Léon Bakst fashioned exotic, lavish set designs to the raves of Coco Chanel. With music by Igor Stravinsky, the world of ballet embraced The Firebird and Petrushka. Picasso and Matisse designed costumes for the Ballets Russes! Nothing like Diaghilev’s spectacles had ever been seen unless, I thought, when Queen Cleopatra had sailed down the Nile in a golden barge.

I rented a tiny apartment at the Ansonia in the early 1990s. The faded hotel was transitioning into condominiums and renting out short-term leases. My studio cost $1,000 a month. The Ansonia was undergoing asbestos abatement, living there entailed a bit of danger. I found a hazardous substance warning ticket inside my apartment the day I moved in, issued by a city agency, stamped on pink paper. I threw it away and relished the roof over my head. I wiped away a powdery film covering the one-room studio and never gave it a second thought. I was glad to lease my very own apartment. I stayed almost a year at the Ansonia before returning to Europe. I had a beautiful view from the tenth floor. Giant stone gargoyles decorated my windows.

My job was lucrative and awful. I worked as house manager for divorced banker Bruce Wasserstein. His sister was playwright Wendy Wasserstein. Wasserstein lived alone in his new apartment on Fifth Avenue. My position had me liaison with vendors, oversee repairs and renovations, handle Wasserstein’s household purchases, and since he had no staff, I also cleaned the apartment. While working for Wasserstein, I studied at the National Academy on Fifth Avenue and won a merit award for fresco.

When my employer purchased art, I received delivery. A priceless Matisse arrived, unwrapped. I placed it as instructed upon a dining room chair. Wasserstein kept two Rothko canvasses at either end of his dining room. Rothko’s works were giant slashes of tonal color; he died by suicide, his works, much lauded.

A former girlfriend sent over a portrait of herself in the nude, but Wasserstein said he couldn’t keep it and to send it back. But he deeply admired the painting. I fell into the unpleasant role of coming to work and finding women at the Fifth Avenue apartment who sought to befriend me, hoping I could advance their situations with Wasserstein. One girlfriend was especially tenacious, moving her belongings into his apartment, only to be asked to move them all out.

The initial months of the job went well enough until Bruce Wasserstein came home early and met me in person. His executive assistant, Lucie Longworth, had hired me. Once he’d seen me, he began slipping out of his office regularly, returning home unannounced. He stripped his clothes off and accosted me in his bathrobe, saying, “I want you to see what you do to me.”

I wouldn’t look because I still thought I was going to become a nun and I’d never seen a naked man. I hadn’t known where babies came from until I was in middle school. A girl told me about sex in a school bathroom and I refused to believe her. How could such a thing even be possible? Personal innocence was something I never seemed to lose hold of and I kept it preciously, like a treasure.

“You really are lovely,” murmured Wasserstein, “name your price,” he bowed his head one afternoon, seated just inside his front door wearing a suit and tie. He’d tried cornering me at the refrigerator door in his opened bathrobe. That had not been successful. He now went to Plan B. He proposed any dollar amount I cared to name, if I would sleep with him. He asked me to have any sort of relationship I wanted. I didn’t want one. Wasserstein never expected a refusal. But he got mine. There are numerous media articles about what an enigma he was before he died. Little was known about the women in his life. I saw them come and go, including one of his future wives. Physically unattractive, but a billionaire, he wanted to buy women.

Sam Jake Seuss, hearing all this about Wasserstein, with me telling him over luncheon at a little eatery near Columbia in 2010 before we were betrothed: “I think anytime anybody does something like that, it should be told.”

While I worked for Bruce Wasserstein, New York City experienced a blizzard that shut down Manhattan’s transit system. The year was 1996 and Rudy Giuliani was the Mayor of New York. I walked through Central Park snowdrifts as high as small mountains to reach the Wasserstein apartment. New Yorkers commuted to their jobs down Fifth Avenue on skies. I helped an elderly woman struggling at a crossroads; snow higher than the top of both our heads. After I had declined Wasserstein’s invitation, I felt it was ‘now or never’ to formally enter a monastery, although my godmother abbess was no longer alive. Lucie Longworth, Wasserstein’s executive assistant, joked that Bruce’s conduct had driven me to a convent.

I worried it might be sad in Rome without Madrina so I picked a severely cloistered order in England on the Isle of Wight.

I gave away all my possessions. BCBG and Valentino dresses, designer shoes, and stereo equipment manufactured by Harman Kardon. Bracelets and rings. Big mistake. I was miserable in England.

I imagined what it would be like to live as Alice in Wonderland inside a warm, cavernous teapot that the monastery used at teatime. The teapot smelled inviting when I rinsed it during chores in the cold, vault-like monastery.

A person of my word, I thought I must remain until I died, committed like a prisoner. But I did not stay long. Their monastery was not the place for me the community’s abbess said. She threw me out, packed me off, and set me free. I headed back to New York, penniless.

Jeannie Campbell was alive at this time, but not resident in New York. I knew Jeannie was a friend of socialite Mrs. Brooke Astor so when I discretely replied to an agency’s job listing to work as a Park Avenue parlor maid, and they offered an interview with Astor, I accepted. I felt I’d be less likely to encounter worldly dangers if I were working as a simple maid, at least until I earned money for a new apartment and decided what I’d like to do for the future. My beauty attracted a never-ending line of would-be suitors everywhere I went, and I wanted nothing to do with men.

I thought Mrs. Astor would be someone in whom I could confide. It was January. I wore a black woolen gown the nuns had sewn. I had no other clothes; I’d given them all away. My parlor maid assignment was to craft floral arrangements. Mrs. Astor liked peonies; I needed to place peonies in precise locations throughout her apartment. I sketched a map of where to place each vase and kept it in my apron pocket.

“I want to take you to my hairdresser,” Mrs. Astor told me. “I want you to meet my butler in the country. He will love you,” and so on and so forth.

“Where are your red dachshunds, Madame Astor?” I asked. I wanted to cuddle them, remembering Weedhopper.

“Boysie and Girlsie are in the country,” she answered. I remained not long enough to meet her dogs.

Fashion designer Oscar de la Renta called and I answered the Astor telephone. I remembered his call years later when I read that Mrs. Astor had succumbed to Alzheimer’s. (Her son, whom I knew, defrauded her of the Astor fortune. Oscar de la Renta came to Mrs. Astor’s aid.)

When I’d been at the Astor apartment a week, sleeping in a spartan servant’s room more plain than a monastic cell, Mrs. Astor called me into her sitting room. It was evening. Her television set was turned on; she was undressed and in her bathrobe. She wore long, drop emeralds in her earlobes. Mrs. Astor had discovered my identity as Lady Campbell’s goddaughter. (The job agency had assumed Jeannie was my former employer when I’d given them her name as a reference.) Worried someone might say she’d committed a social faux pas by employing me as her maid, “Why did you do it?” Mrs. Astor asked plaintively. “You are not a parlor maid.”

“I had no place to go and must earn a living.”

“Alison, I shall tell everyone what a nice lady you are, if anyone ever asks,” she said. Handing me a check for $100, she sent me out of her home and into the night, scandalizing her cook (who worried over my well-being). In a doorway on the Upper East Side, I huddled near where I’d lived with Metamorphosis actors until daybreak.

My next job through the same agency was for Andrew Rosen. Rosen’s father had founded Manhattan’s Fashion Institute of Technology and been a top executive at Calvin Klein. The job interview was not with Rosen, but his partner Elie Tahari. Tahari hired me as an assistant for his wife Rory. But my first day on the job, after surprising me with a lily on my desk and a note that read “Welcome to the world of Tahari,” Elie introduced me to Rosen.

Andrew Rosen was in trouble and said, “Nobody but you can help me.” He was recently divorced with two pre-teen children and about to launch the fledgling Theory clothing brand. He’d heard I was from a monastery. The early days of Theory were intensely busy. Rosen had run through multiple nannies and his home was in crisis. I said, “Yes.” That was my first and last day at Tahari.

Theory jackets were long, black, and fitted. A year later, The Matrix would hit theaters and long black coats become hot fashion tickets. But in 1998, nobody wore the look. Rosen took a risk. I assisted Andrew Rosen by running his household and I loved his son and daughter. Rosen was rarely home so I stayed over at his apartment across from Lincoln Center, unable to leave the children unsupervised. A housekeeper was present during the day, but at night, I slept in the Rosen living room more times than not, although I rented an apartment on the Upper West Side.

Retired tennis pro John McEnroe began sending his son over to me at the Rosen’s. Soon I had two boys instead of one. Sean McEnroe was a lamb, but not at first. The boys had me take them to a film. It seemed harmless enough, but suddenly there were naked women on the screen with giant, artificial breasts. I stood up in the theater with both arms outstretched. I whisked the boys out like a chimney sweep. They thought it was funny, acting up all the way home in a taxi. But I kept loving them, tirelessly being good to them, until almost instantly, we were happy and in full accord.

I wore Theory and so did Andrew Rosen. In the apartment building’s elevator, Ashley Rosen looked her father up and down, and then to me: “Theory man and Theory woman.” Six months of roller coaster eventfulness ended when I applied to Columbia University and was accepted as an undergraduate.

Rosen wanted his children to have every license and I disagreed with him many times. No drugs. No pornography. No drinking. His allowance of these things and my refusal caused a rift.

Once enrolled at Columbia, I met with strong prejudice, beginning in a painting class. Unknown to me, the academic administrator in charge of my registration aspired to be a screenwriter and was taking courses in Columbia’s Film Department after work. I was subjected to a series of tortures. Why, indeed? Those outside of the Columbia culture are unaware of the rigid bigotry that prevails therein. In body and face, I looked like an undergraduate, but I was in my late 30’s (I’d spent my college-age years in cloister and it was as if God handed them right back to me). Feckless Columbia folks simply couldn’t stop gasping and clucking about my age. My first year at Columbia, I kept entering the Dodge Hall painting studio to find obscene cartoons affixed to my easel and my unfinished paintings damaged.

I didn’t know who did it, but the bullying intensified. Soon my paintings were no longer merely defaced but outright stolen, removed wet from my easel and spirited away. Graduate students from the Film Department hung out, waiting and watching for me, their gossip flying. I was the talk of the School of the Arts. The administrator/screenwriter seemed jealous of me, but I had to meet him for paperwork and course registration because he was my assigned academic advisor. He tore through my student folder, tossing out recommendations that lauded my character and accomplishments. “I am going to regularize your folder!” he growled.

Right. What?

I had told Columbia faculty and administrators that I’d recently worked as a parlor maid. “She’s a housekeeper!” I heard them say. “She doesn’t belong here!” Walking into the academic office for mandatory advising appointments, a female dean said on seeing me, “The infamous Alison Winfield.”

My computer science professor said he’d never heard anything like it in during his entire experience in academia, when administrators phoned his office, forbidding he allow me to take his class. Other students whispered as I walked by, “She is working class,” while administrators chimed, “We’re classist!” They were proud to be ignorant boors. I was more than kind to all. I wrote essays for other students, did their homework, mixed their paints in my studio and cleaned up their messes at my dorm. I suffered the abuse quietly throughout my tenure as a student.

Professors manipulated my grades. A Visual Arts departmental head cursed me in the hallway of the School of the Arts: “You are going to fucking be like everybody else!” Other students told me he made them turn my paintings to face a wall during his classes. My paintings were so interesting they proved a distraction to the other students. Most of my early paintings were Madonna and Child portraits. He said he’d have done everything for me, had I been Jewish.

I felt Jewish because Jesus Christ was Jewish. Jake Seuss and Ginsberg were Jewish, too, only I hadn’t realized it. I saw people, not tags. I saw people for who they were inside.

Columbia said I was an older student and they had no obligation to fund me. They said I should transfer to another school that was less expensive or give up school altogether. I refused. I worked before and after class and every holiday. I lived in a Columbia University Residence Hall and charged my room to my tuition bill. One winter I had no shoes and no coat. It was all this and more that the Columbia administrator who helped me when I was homeless & betrothed remembered; she saw it all happen, the student years and my engagement to Jake Seuss.

I took graduate classes as an undergraduate because my abilities required meatier content than what Columbia College offered. I attended theoretical physics seminars and discussed string theory ideas with Brian Greene, who thought I was a graduate student.

In the run-up to the Iraq invasion by US Coalition Forces, I’d studied Middle Eastern cultures. I recognized the wedding festivities of local custom when merrymakers shot ammunition rounds into the sky and the US Government said the people had engaged in hostile fire.

I wrote for the Columbia undergraduate newspaper Spectator and contributed also to a School of International and Public Administration graduate publication. I spoke out about the dangers of invading Iraq. Secretary of State Colin Powell fed America a load of bull and they swallowed it. Intellectuals all knew sanctions against Iraq following the Persian Gulf War had reduced Iraq to the point of impotence. I discovered a website in the Middle East that included secret information on the state of Iraq’s Weapons of Mass Destruction non-capability, and as Iraq was bombed, the site posted real-time information that showed Western media reports to be false (fake news). I gave the site information to one of my former professors. He used it for his own purposes. I ought to have known better, I’d gone to him and reported widespread sex abuse of children in UN refugee camps by UN officials. He was head honcho on a Human Rights commission. I handed him deeply researched information and proof of the abuse and asked him earnestly, “Who will help these children?”

He glared at me, pulling up to his full, tall height, “Nobody!” He was a leader refusing to lead. As a Columbia student, I approached numerous world leaders on many issues of justice. What I did not realize: in general, leadership itself harbors corruption’s rooted bulb. I was giving the information to the very people most likely to abuse.

Looking back, I stagger to recall the amount of research and outreach I did on behalf of others, especially my work in the area of international Child Rights. (I could write a book about that one topic alone.) To escape the Columbia Administration, I wrote a research proposal to study the atmosphere of planets Jupiter and Saturn at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena. JPL was part of NASA, operated by Caltech. I left the Columbia Administration to gnash their scrofulous gums and headed for the balmy West Coast; in 2004, I was the sole Columbia student to win a nationally competed Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship at The Jet Propulsion Lab. This was the year Cassini spacecraft began to orbit Saturn and I was present at JPL for orbit insertion.

Caltech was exquisite. I flew from New York City to Los Angeles and thought I’d gone to Heaven. Caltech had two outdoor swimming pools and red roses growing on long stems as high as my shoulders. Caltech Campus had bullfrogs and lily pad ponds. Turtles. Crows. Exterior soapstone corridors I ran over barefoot. Caltech offered linen service to students. Fresh sheets and towels every day, if we wanted. Students were prized and pampered. A vast difference from the way I’d been treated at Columbia.

Caltech physicist Kip Thorne (Nobel Prize in Physics) used to eat a tuna fish sandwich and watch me work through light cones at his blackboard. He offered me half of his sandwich. I told him there was more to light than we knew. He looked long and thoughtfully at me. He became a colleague with whom I could discuss physics and exchange emails:

On Dec 25, 2004, at 12:18 PM, Alison Winfield wrote Kip, a paper claiming a new neutron half-life and redoing BBNS: Mathews, G., Kajino, T. \& Shima, T. 2004, astro-ph/0408523 “BBNS with a New Neutron Lifetime”

new tau_n = 878.5+/-0.7+/-0.3 sec, 6 sigma lower than old world average. Predict Y_p = 0.246 instead of 0.248 with WMAP or Tytler D/H values of \eta_10=6

Ned Wright at UCLA gave me this citation today; this makes the p-p chain go faster but minimally so (1%?). I think I now recall who put forward that it is substantially slower. Someone from Princeton came here talking about lithium experiments. I have lots of stuff to learn without chasing this, but if I can find out, it is an important detail.

Alison

Date: Mon, 27 Dec 2004 09:08:28 -0800

From: Kip S. Thorne

To: Alison Winfield

Subject: Re: proton-proton chain slower

Alison,

If there is strong evidence for this, then it will show up again somewhere that you or I will see, so don’t spend much time chasing it.

Best wishes,

Kip

I returned to Columbia University, took a job at the United Nations as an interim speechwriter and Deputy Permanent Representative Secretary for South Korea and concluded my senior year of studies.

My favorite class was in plasma physics. I attended the class as an unofficial auditor. The course was for PhD graduate students. Five males sat in the classroom. Our instructor was a brilliant Massachusetts Institute of Technology alumnus, Thomas Sunn Pedersen.

“Can anyone tell me the meaning of one of these equations?” He chalked up several plasma physics equations and stood to the blackboard’s side, waiting. He waited. No boy in the class raised a hand. Pedersen looked like a child opening Christmas presents. I could not bear to see him disappointed. I cautiously raised my arm. All eyes fixed on me. A girl among boys.

“That one,” I pointed to the most complex equation on the chalkboard.

Pedersen leaned his back against the concrete block wall inside our Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Sciences classroom, eyes wide with hope. And I blew him away: I described a little dance, a walk: plasma diffusion across a magnetic field. For me, his class was like someone handed me an ice cream. I loved it. And for several more years, at another institution, I undertook graduate studies in plasma physics. I told a senior scientist that the colouration in the atmosphere of Jupiter could be due to living microbes. I had cutting edge instincts and an uncanny ability to make advanced analyses. But all over again, it started: I was gender and age bullied, this time to the point I stopped studies and abandoned my last NASA fellowship. Of course, I reported all this and tried to get help, but the system was corrupt. And people were cowards.

“Don’t tell me,” said multiple senior scientists and professors, “or I would have to do something about it.”

After intense bullying in the Arts at Columbia, I had stopped painting for 7 years and done science research. Now I screeched to yet another halt.

I ardently wished to be happy. In 2010, I searched my heart for true friends and remembered the Kerouac School. (I’d looked for Jake Seuss when I began studies at Columbia in 2000 and located him teaching at a small Virginia college, but I read a news article reporting Jake Seuss as involved in a sex scandal with his students. Could it be? I saw his picture. His name. And I didn’t reach out to him.)

In 2010, I wanted to speak to Jake Seuss again, even if he had done as I’d read. After everything that had happened in life, I wanted Jake Seuss. Nobody else would do. I loved him more even than my Madrina.

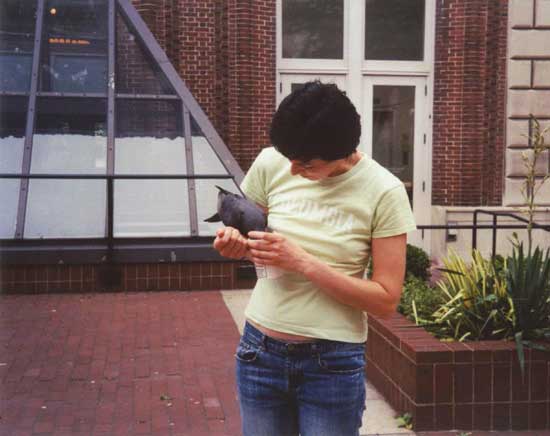

Other than Jake Seuss, I’d had one major love in my life, the little dove named Lambish and she was recently dead by poison. Lambish had come into my life unexpectedly in 2002. One afternoon between classes, I had walked across campus in the rain on Columbia’s main plaza and spotted a small bird without feathers: a baby pigeon (rock dove). “Lambie, Lambie, Lambish,” I called to the baby bird. I thought she was perishing so I comforted her, speaking softly. “Lambie” was the sweetest thing I could think of to say. The next day the bird was still there. I’d brought her a pinch of scrambled egg from our college cafeteria. To my delight, Lambish ate the egg. I had no money to purchase seeds, but egg seemed to go over well. Lambish grew into a ravishing beauty. Silvery grey feathers sprouted all over her body. When she could fly, she began to roost atop the columns of Low Library. Low Library was Columbia’s old library before they constructed Butler Library during the 1930’s. Currently, Low Library houses offices of the University President and Butler has all the books (over two million volumes).

Lambish began to follow me around campus, escorting me to classes. Soon, all the birds befriended me, even sparrows. One day, I spoke with another student about a quantum physics exam we’d taken. Lambish perched at my arm. I grasped a large pecan from John Jay Cafeteria. I held the nut in my hand, engrossed in discussion, but Lambish waited not, her excitement grown too monumental. The boy’s face suddenly reflected fear. I stopped mid-sentence, following his gaze. I saw the pecan slowly disappearing down Lambish’s throat. Holy ham hocks! I moved her close to my face. We were eye to eye. Would she choke to death?

“Lambish!” She swallowed the pecan with great determination. Then she smiled at me with her eyes. “Mommie’s girl,” I said and breathed a sigh of relief.

Lambish also enjoyed soaring at high altitude. One day, in gusting winds, she spotted me from overhead and sailed down towards my arm. Blown off course, she crash-landed at my feet in front of Low Library and the alma mater statue. “Lambish, darling,” I covered her with kisses. Lambish was my chief happiness at Columbia. If I could have one thing back again, it would be her life.

In 2010, Jake Seuss swept in to rescue me from despair by loving me. His heroism was the tonic I needed. I wanted to be friends again. “Impossible,” he said, “I can’t.” Jake Seuss said we were lovers. Jake Seuss cured my heartaches. He was the boy I’d most been attracted to, the one whose company I most relished. The boy I liked best. He was the only one I would ever accept as a lover. I accepted him with open arms. He said it wasn’t true about his sexual exploits at the small college. I believed him.

10. Homeless Newsreel

(Blue Hydrangea)

Reader Road Map: homeless, 2012-2014.

Inside Butler: Thursday, January 2, 2014, 10 AM: I am drinking a coffee so hot, my mouth burns. Columbia has lots of free coffee.

I pop down the Library staircase to visit Security. A Columbia University guard sits at the front door of Butler Library. Once inside, students run wild and unmonitored, bounding through heather with Brontë, drinking wine with Hemingway, sword fighting with Dumas père, fasting with Dickens, lolling in opium dens with Zola, sleeping in Juliet’s tomb, or maybe just reading online news. Rushing to the Security desk at Butler’s front door, I tease the guard, saying urgently, “I just got a call from the President’s office” (Columbia University’s President Lee Bollinger).

Not only does the guard stop everything to look at me, but other people around his desk do, too. University Facilities employees are standing inside the Library door, ready for the snow removal on campus to begin. We are in for a major storm: near-blizzard conditions. New York Daily News runs the headline: HERCULEAN BLAST!

“We evacuate at noon.” Everybody stares with renewed optimism. “Butler Library,” I say, nodding my head meaningfully. An older man sits nearby, listening; his eyes begin to wink rapidly. Security is used to my larks. I delight in pranks. But for a second, they all believe me, until I begin laughing.

Butler Library is in for the long haul, though. We sit assembled and Hercules is coming. I love Columbia Security. They are darling. The ladies are nice, too, and ravishing beauties, especially Miss Scott and Miss Palston. Female officers wear pretty lipsticks and fashionable wigs. The only thing that would be more exciting is if the lights went out and we were left in the dark in Butler’s marble, giant-ceiling chambers.

10:20 AM next day: the lights did go out in Butler, if only for about seven minutes. Twice. Today Butler is closed entirely. This never happens. But the storm is that heavy. I am lucky to be inside the Student Center, a building with an enormous glass wall. I can see snow as I type. Last night, Security had to turn us humble scholars out into the snow at 3 AM because the student study-space we were using was suddenly off-limits: I treacherously walked the few city blocks to Tom’s Restaurant on Broadway (open all night). Tom’s is famous as the New York City deli frequented by Seinfeld in his TV show. I ate fried eggs and hash browns with ketchup.

Tonight, I shall have to explore the bowels of Manhattan in Émile Zola fashion and ride the New York subway. It will be warmer underground than outside in the blizzard.

The New York Times reports that our weather today is the same as that of Fairbanks, Alaska. Jake Seuss texted me last night: “Remain safe and warm,” and with such sweet fingertips typing, his message keeps me safe and warm.

I remember my betrothal to my sweetheart started in springtime, almost four years ago, when hydrangea bushes blossomed blue along the front face of Butler Library. Among the hedges, I could smell whiffs of oleander flowers. Sugar molecules in hot sun and the fur of honeybees bristling with pretty pollen.

Leave a Reply