Here are all of the installments:

Part I · Part II · Part III · Part IV · Part V · Part VI

11. Jack Kerouac School Revisited at Columbia University

(Sam Kashner and Honeybee Panties)

Reader Road Map: Sam Kashner (aka “Sam Jake Seuss”) plights his troth. News topics: Wall Street Crash; Fukushima power plant meltdown; BP Gulf of Mexico Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

After graduate studies, I worked in Manhattan as a research and executive assistant at a nonprofit in Harlem. During that one year, Obama became president and the United States awoke to a full-scale economic crisis. The nonprofit relocated to an outer borough and I stayed in Manhattan.

I took figure painting classes at the New York Academy of Art and made an application to their MFA program. It was fun to be back in a studio and they had good models. My undergraduate expertise had also been the painting of female nudes. The Academy selected an oil portrait of my dove Lambish for their first annual “Deck the Walls” juried exhibition in Tribeca. A collector bought my Lambish painting off the wall, sale proceeds going to the Academy. Other painters in the exhibition included the Mary Boone Gallery artist Will Cotton. Cotton paints women with cake icing, macaroons, gingerbread and candies on their heads.

”Cahill Elementary Extravaganza” by Alison Winfield-Burns, oil on linen, 24 x 36 inches, 2018

At Columbia, my teachers had been Tim Gardner, Richard Phillips, and Elizabeth Peyton, all strong portrait artists. I was in solid artistic company, but this was a deeply unhappy time for me. Lambish, whom I tenderly loved, had just died. And the Catholic sex-ogre scandals broke my heart like a crucifixion.

I decided to look again for Sam Kashner, even though I read he’d been involved in sex scandals, too. Sam wasn’t easy to locate. Via a poetry website, I found him living in Manhattan. I sent Sam an email and he answered instantly. At the same time, I reached out to Larry Fagin, our old teacher from the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. He still lived in Lower Manhattan. I was tenaciously trying to find Peter Orlovsky, but with no luck.

I knew Allen Ginsberg was dead.

I wanted my friends; these men had been my earliest comrades, and I yet loved them.

I felt a kinship in that Ginsberg and I had both been Columbia undergraduates (fifty years apart). Columbia campus has white roses. Shrubs interlock with bits of morning glory.

But even Columbia’s beauty could not heal my disconsolate spirit. I wanted my truest friends: I wanted to see Sam Kashner (“Sam Jake Seuss”).

Sam told me he was writing for a glossy magazine and living in Manhattan. His first email recalled my long skirts.

Sam answered like a bullet: “Yes! And I remember your dresses which seemed like gowns. And your work, which I’ve just walked myself through, is beautiful and has already left a powerful mark. I would very much like to see it and you in real life. Choose a day. I live on Mott Street between Houston and the street formerly known as Prince. S”

“I would love to see you, Sam. Is there any way that you could come up to Columbia, which is 116 and Broadway? I graduated in 2005, but I am in the Commencement this year, next Tuesday. I live just off campus. I am in the library now. You name the day, and I will meet you, just not Tuesday.”

“You should be feted for your graduation. If there’s any way to see your work that would be wonderful. Otherwise, could you bear to come down to the East 50s–would take you to my Vanity Fair boss’ restaurant, the re-awakened Monkey Bar–with its Monkeys in bellboy-hat ashtrays from the 20s and it’s old New York murals. It’s a guilty pleasure, but we would be very welcomed there/and please bring more images of your work. Evenings are always a bit easier, crashing stories in the day, but if lunch beats dinners, I’ll just skip out. How does Wed/Thursday sit with you, Alison? If midtown is your idea of a circle of hell I will drift up to you. S”

“Sweet Sam, it is so thrilling to be grown up, isn’t it? I haven’t really changed, though. And I can recall sitting on the floor with you at Naropa while Trungpa Rinpoche spoke endlessly saying ‘still I remain chrysanthemum.’ Seems like just the other day.”

“Thursday. In fact, you are too glamorous and breath-denyingly gifted for that joint, but it would be fun. Would you eat your dinner at 7? I’m so sorry I missed your show at the Academy. There will be many more. So pleased you did this and to see your work it is all such a privilege, a tangible ecstasy, and yes, you’re right, grown-up life, and all sorts of big abstracts, but it is much more. The hour has begun to witch, so I’d best away. Thursday then.”

“Okay, I shall come there at 7. I rarely go out, dear Sam, and so I hesitate to be out late. I scarcely even attended the Academy show because it was packed with 600 people. I live very obscurely. I donated a painting to the International Rescue Committee of ladies having tea at a Darfur camp. And the painting that I sold at the Academy also went to charity. It will be so great to see you. Thursday. You could pass me the address and say if you will await me at the door? Else, I am a member of the Princeton Club; we could meet there at 43 and Fifth. But if you tell me the address of your posh and chosen location, I will be there.”

“Honoredelightedandso pleased you are breaking with tradition a bit and meeting me. Perhaps the more painterly friendly Waverly Inn–also Graydon’s other watering hole–would be less of a scene, and not so lousy with swells. You are not only making art in the world but being in the world with a heart as warm and powerful as your art. Yours in awe, Sam”

“Sam rose, really, I care not where we sup, I simply wish to see you and to be with a friend who is as able to be sensible and conversant as I am. Haven’t you noticed in life that there is a dearth of intelligence out there in the human environment? Monkey Bar is fine, whatever. I shan’t be paying a bit of attention to anyone but you. I was thinking that we could have a glass of prosecco or champagne and gab endlessly, but not as boringly as Trungpa Rinpoche. Sam, how naughty, but you know that he was a complete fake and his talks were grossly long-winded. Still, his chrysanthemum comment was worth the trouble. I really liked it at Naropa. And I was a teen queen. Youths today don’t have the same heart. I saw Allen in New York before he died. He was the same, kindly man that he always was. Tell me which place to meet you and what time. I shall be there. They say that it will rain on graduation Tuesday.”

“Thank you darlingest Alison for the image of you with your winged muses. (I sent him images of my doves). How lovely you look together. I would eat dandelions out of a paper bag w/you. But we’ll seek shelter from the stormy seas somewhere quiet enough for us to hear each others thoughts and eat lettuce until like Peter Rabbit we are practically soporific. Hopefully the skies will clear for your lovely day, and congratulations! I am admiring of your achievement, your art, and your appealing self. So much to say about the Trungparian past, the present life, the future, and how you so sweetly swept into mine. Another reason to be grateful to you. And all your good deeds in a naughty world. I look forward to being in your company. Devotedly, Sam”

Unknown to us, my love was about to hurl him into the best he’d ever been, a Hercules on a fine Arab charger, a Helen of Troy, a Zeus among men and a Jesus walking on water. And he was about to give me the romance of my lifetime.

Fagin was faster to reach than Kashner.

I sent a note: “Dear Larry, I wanted to ask how you are. You were a great poetics teacher back in the heyday of early Naropa.” I quoted a poem he’d written me back in the early 1980’s: A fish, a sweater of senses. Every rock in the world is wadded up gold foil.

He answered: “Yeah. Are you here? Come over for tea next week?”

“Do you live downtown at the same place with the gold fridge and Richard Hell? I could come later in the week.” Richard Hell had been in a band called the Voidoids with one of the Ramones. And he lived in Fagin’s building near 12th Street and Avenue A.

I planned to visit Fagin, but first, Sam said we should meet for dinner. He chose the place and time. I prepared a special gift for him. A large drawing on finest watercolour paper of Marilyn Monroe that I’d done for my New York Academy of Art portfolio. When I arrived at the restaurant (The Monkey Bar), Sam didn’t show up (I had sewn white campus roses into my blouse and worn a lovely gown) so I wrote him an email that I was going to see Fagin and would check back with him later.

Larry Fagin lived on Twelfth Street and the Lower East Side of Manhattan was more built up than I remembered. The Lower East Side nurtured hardcore music clubs during the 1970’s, places like Max’s Kansas City and CBGB’s, featuring the New York Dolls, the Sex Pistols, and Lou Reed, but before punk rockers and the Beats lived there.

A postman held the door propped open, delivering mail. I rang Fagin’s buzzer anyway to give him notice I’d arrived and began to climb upward, the same 4th-floor walk-up I remembered well. Fifteen or twenty years ago an old woman used to lean over the 5th-floor landing when she heard footsteps. She’d clutch a small bag of rubbish and ask whomever she found on the stairs to take it down for her. I last saw Larry in 1992 and she was there; I took out her trash.

Fagin waited outside his door, pleased and smiling, without any shoes.

I smiled, too, “Larry, you are exactly the same! Only your hair is white.”

Fagin took my head in his hands and kissed my brow. Only then did he let me climb the last step to walk into his apartment.

Immediately on my right was a bathtub, covered by a kitchen counter. Fagin had made the kitchen nice with pretty things and a sunny window. The rooms were not large, but interestingly shaped, not squares or rectangles. The rooms had odd-cornered walls. Fagin first rented the apartment in the 1960’s. Cheap rent, good space, great location.

I noticed a couple of changes with Fagin. Moustache and goatee; longer hair. His body was still the same strong barrel shape, but his movements had slowed. His voice, and his asthmatic breathing, sounded as they had thirty years ago at Naropa’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics.

“Larry, you’ll never guess what happened yesterday. Remember I said in my email that I had been stood up? Well, it was Sam!”

Larry Fagin’s expression grew stern.

“How did you find Sam? Is he in New York?” Fagin spoke offhandedly, but I sensed his deep interest.

“It’s not just you, you know, he does that with everybody,” said Fagin, “He’s a pathological liar.”

Sam was extremely popular everywhere he went and people became angry when deprived of his company. I thought that was the real meaning behind Fagin’s severe pronouncement or maybe Fagin didn’t like it I’d been stood up. But then I saw it was something more. Fagin explained Sam had written a memoirabout Naropa (I didn’t know about the book). Sam’s memoir offended a lot of egos and Larry was still mad.

“I don’t mind, I just forgot Sam stands people up. He was always doing that at Naropa. I was crazy about him anyway,” I added.

We began to reminisce and I asked Fagin about a mysterious incident from Naropa’s past. Faculty would not talk about it years ago, but I remembered the JKS poets had been hostilely divided and I’d always wondered what happened. M.S. Merwin was a poet from Princeton who got involved with Trungpa in a way that ended in bad feeling. A big chunk of the Boulder intelligentsia were Buddhists and students of Trungpa Rinpoche, but the poets were just a bunch of poets. Some embraced meditation and some didn’t. Allen Ginsberg asked everyone to at least check it out; he was the biggest Buddhism fan among Naropa’s writers. Trungpa retained a bodyguard retinue of willing, elite local people called the Vadjra Guard.

“Vadjra smadjra,” said Fagin, “I wouldn’t have cared what they did to Merwin!” I was finally going to hear the carefully guarded, secret story of M.S. Merwin and Trungpa Rinpoche.

“Larry? What happened with Merwin?” I pressed.

“Merwin? He wanted to be in the advanced Buddhist studies without doing anything, just because he was Merwin. Whatever happened to him is his own fault. He pushed until Trungpa finally let him in, but then Merwin objected to the violent imagery—people with their heads cut off.”

“This wasn’t violence. It represents the chopping off of ignorance.” Larry said, “Merwin didn’t understand. There was no Vadjra Guard then. They didn’t call themselves that. Anyway, Trungpa wouldn’t have done anything.”

“I liked his sayings,” I said.

“They’re great,” Larry agreed.

“Once, we were all standing in a line, at a Buddhist reception,” continued Fagin.

My ears perked like those of a sled team husky; I listened carefully and took notes.

“Trungpa walked up to Anne Waldman and struck her in the chest.” Fagin looked at me. “Hard. She was full of herself, bossing everybody. It was a lesson in humility.”

Fagin divulged that Merwin and a girlfriend went on a high-level Buddhist retreat and during proceedings, Merwin and the girl were forcibly stripped of their clothing, demonstrating a lesson in humility. And basically, Merwin dropped Naropa.

“It isn’t the same thing, meeting people now, Larry. New people don’t have the deep attachments like those we forged at Naropa.”

“I know,” he said. Our visit was coming to an end. Fagin had a writing student arriving any minute to the apartment. Fagin took my hand and examined the perfectly formed fingers, “Your hands don’t even look human, Alison. You are like some exotic animal.”

Fagin was about to shut his door, but yanked it back open to add, “And stay away from Sam!”

I laughingly held up the palm of my hand, “I think there isn’t any danger! Sam might keep standing me up and never meet.”

Fagin and I hoped to see each other later in summer. My plan was to reunite all of the living Naropa poets I remembered so dearly. I had found Fagin and Kashner, but not my old friend Peter Orlovsky. Nobody seemed to know where Orlovsky was and he was then seventy-seven years old.

Next day, seated in Butler Library, I got an email from Peter Hale (Director of the Allen Ginsberg Estate). Hale had been Ginsberg’s student a few years after Sam and me.

Hale messaged me that Orlovsky was in Vermont on his deathbed: “Dear Alison, he’ll probably not last too much longer, but at least these last days can be in some form of comfort for him.”

Sam and I exchanged a volley of emails while I tried to rush to Orlovsky’s bedside before he died.

Sam started speaking in the language of love and promising to whisk us both unto Orlovsky. “Darlingest Alison, my heart was even younger then,” he wrote, “and hardly acquainted with the world. I adored you but behaved awfully. When you are young and staring like Narcissus into the mirror’d river, you tend to run from love itself.”

As much as his romantic tone appealed to me, I wanted him to take immediate action to see Peter Orlovsky. I wrote back: “Listen to me: I love you. Just remember that and come home. We must the two of us go to see Peter or go to his funeral. The two of us. And your face is exquisitely beautiful to me. Don’t leave me again. Just come home.”

“For you, darlingest Alison, I would walk through fire and over broken glass. There’s a longish poem of Kerouac’s, imagining all his friends and family in heaven. Allen will be in ecstasies/Peter amazed. It goes on like that. To read it now, it’s so strange, dear Alison,” replied Sam. “When he wrote that it was a kind of fantasy, because they were all in the world, and now, poof, they’re gone. I will try to make it darlingirl but if we don’t make it, please don’t stop loving me as I love you.”

Sam said we could make it in time to Orlovsky’s deathbed and I wrote to Hale that we were coming. This went on for some days. Until it was too late. Peter died. Sam did not come.

Seated on a grassy lawn of Columbia, doves and sparrows surrounding my person, I composed a poem for Peter, the first poem I had written in many years.

Blue PoemPeter likes to wear blue,

suits and sandals with socks,

a shirt of the ‘frist’ blue,

a tie of the first and last blue

and all else should be cerulean.

Peter is the best love

and he will have his own dove.

Peter was known for incorrect spellings and my use of ‘frist’ in place of ‘first’ was a hat-tip to Orlovsky. Later in life, Orlovsky had been jealous of Allen Ginsberg’s other lovers, which is why I penned Orlovsky was the ‘best love.’ I wanted Peter Orlovsky to know I remembered him and cherished him. Blue was Peter’s favourite colour. I remembered he wore blue at Naropa, mismatched and multi-toned. (This poem was later printed in Bombay Gin, a Naropa publication, but with the word ‘frist’ misquoted to read ‘first,’ for alas, the editorial people at Bombay Gin no longer had any personal knowledge of Orlovsky or why I would have intentionally used an irregular spelling. The incident motivated me still further to go on record and truthfully expound, as Barbara Streisand once sang, “the way we were” in memoir before none of us are left alive who knew anything first-hand.)

I thought of the Naropa dances where I’d worn silks and antique laces. One night, I attended a dance wearing a 1920’s original flapper dress in cornflower blue chiffon. The hem cascaded in leaves of fabric. The neckline was ivory silk and the buttons were genuine pearls, set with rhinestones.

I remembered suppers with Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky—one, in particular, when Orlovsky cooked dinner for the three of us with a menu of shrimp spaghetti and pink wine. While Orlovsky cooked, Ginsberg asked me to play the piano, handing me a copy of the “Maple Leaf Rag” (composed by Scott Joplin). I played rather badly, but eagerly, sunlight streaming through the windows, strong in late afternoon, waiting for shrimp to boil.

“Now we want you to tell us your life story,” said Ginsberg. We clustered together at a linoleum table pushed against their kitchen wall. After the life story (of babyhood and early teenhood) and the repast, Peter Orlovsky and Allen Ginsberg grew protective of my welfare (exchanging glances during the meal when I told about the abusive parts in the South). I never forgot their many sweetnesses to me and Ginsberg’s whispered comment to Orlovsky, “Alison Burns is a really pretty girl.” They were both respectful to me, like some sort of Boy Scout badge of honour, treating me as something worthy of preservation.

“They were good people,” I spoke into a microphone, reading my “Blue Poem” at Orlovsky’s Manhattan Memorial. Six hundred people attended. Rocker Patti Smith played guitar. Afterward, I rushed back to Butler Library to send Sam a detailed account of the whole thing. The Memorial had also been videotaped (capturing me, in a Columbia t-shirt and hair in ponytails, at minute 10). Anne Waldman was there, and I kissed her on the cheek.

Sam said seeing Anne Waldman would be for him a terror worse than death because she was angry about his memoir. But he was wrong, they would all have embraced him with open arms. I told everyone Sam and I were engaged and asked them to forgive him. Hale said he’d make sure Sam was welcome and even write to him with an invitation.

It was June 2010 when Jake Seuss arrived to find me at Columbia University (Orlovsky died in May). I anticipated my old friend at the front gates of Columbia, wearing a long black skirt, full and embroidered, with a sapphire blue tank top, the same thing I’d worn at the Orlovsky Memorial. An hour passed and Sam never appeared. Tourists took my photograph because I sat with my white dove Neve on a little curb beneath a shady lane of trees.

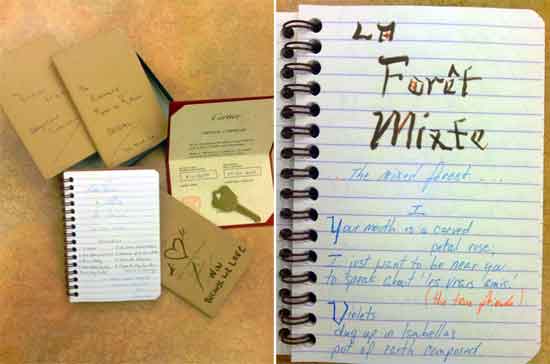

I called these trees la forêt mixte (the mixed forest). They provided a canopy of dense foliage and when in bloom, a heady perfume. I owned no cell phone. The only way to hear from Sam was to go inside Butler Library and check my email. His message said there was a flood at his apartment on Mott Street and he could not come to Columbia. I said he should come anyway or never come at all after all the procrastination. A little later, a Columbia University Security guard told me Sam was at Butler’s front door, hat in hand.

Sam stood in bright afternoon sun. His nose was runny from a cold. I threw my arms around him and kissed his lips. A kiss on the mouth! My instant reaction to his presence. I never kiss, but Sam was a living miracle.

“You are strangely unchanged,” he marveled. We ripped all bombast from our eyes and looked at one another, angel-headed. That means we zoomed back to Kerouac School in our hearts, young and blissful.

Sauntering through campus, we reached a patch of lawn.

“Feel it,” I patted lush, green grass with my hands. Doves flew overhead and spun back around in the sky.

I called them by their names and one by one, they dropped to the grass. I introduced them to Sam.

“Your winged muses,” he said with awe in his gaze and the kind of love that has the power to climb alive out of a tomb.

We held hands. Life anew sprang like primroses before us; we never dreamed we’d have this second chance. Over the next days, weeks, and months, we embarked on the romance of our lifetimes. Everywhere Sam and I went, we were the center of attention, our magnetic kissing and cooing drawing all eyes.

“Don’t read it!” Sam said. We sat together at an outdoor cafe near Columbia. He meant his memoir about JKS. One reason I shouldn’t read was there was a lot of mention about hurricanes, tornado winds, unemployment, labor unions and toil. I eventually peeked inside a copy at Butler Library—the book almost made me want to go out and collect Social Security benefits or buy a life insurance policy: Sam’s memoir described “blow jobs.” Wind and work, sex, what the heck? I wondered. And another part said he’d slept with the wife of one of our most venerable teachers and he used her real name.

On another restaurant outing with Sam near Columbia, I sipped a glass of Chardonnay. My back was against a wall. We were cozy. I had brought him a gift, a copy of Lang’s Yellow Fairy Book, published in 1894. I was deeply in love with Sam, but I still planned to one day become a nun. Yet the pull of the boy was getting stronger. Seeing him again made my heart whole and mended all life’s hurts.

Sam urged me to come to his apartment and one day, I agreed to arrive by taxi from Columbia. The cab shot down a riverside highway making good time, but when it reached his dwelling, Sam was not waiting for me as promised. I had journeyed without cash for the fare but had a debit card. As I paid the driver, Sam flung open the car door. He said he saw me from his upstairs window and ran down quickly.

He insisted I go first up the steep stair of his apartment building that looked like a dollhouse, while he followed closely, “I’m on the level with your flip-flops.” They were pink Reef’s. I climbed higher and higher. It took both hands to hold up my trailing skirt.

“I remember the back of your neck from Naropa,” Sam said, an M-shaped dip at my nape, visible to him because I wore my hair in two ponytails.

Inside his cute apartment, a one-bedroom with French doors, I asked for a glass of water. The apartment interior sparkled. “Who cleaned everything?”

He hung his head.

“You did?”

He said he cleaned the apartment himself for my visit.

“I don’t like water because fish have sex in it,” Sam was saying, handing me water. I pushed it away. Why would Sam say ‘sex’ to me?

“I want to go home.” I escaped to the door.

“You do? Alison, will you wait for me?” Downstairs, I placed my hands on the street door, pushing it open. The door was greasy. My hands got sticky.

“They polish it, Alison.”

We rushed to a corner bistro so I could wash my oiled hands. I couldn’t touch my dress or hold up my gown. We entered a back restroom, but the lights were off. I couldn’t feel the switch so Sam stepped into the bathroom with me.

“I can’t see the soap.” We stood in darkness. A white soap-brick hung suspended from a wall by rope. “Gross.” I said, thinking of germs.

“They have soap like this in Brazil, Alison. Look, it’s a fresh bar.” We washed our hands together and then he selected a table in a nook, overlooking a street.

“Hi!” The waiter liked Sam—a regular customer. I poured my darling’s glass full of water before I filled mine. He watched me pour. So did our waiter.

“Bring me a glass of laudanum,” I said. The waiter paused, confused.

“Laudanum?” he asked.

Sam knew my intention. He’d read Edith Wharton and the same Victorian novels I had. “Heroin, it’s a kind of heroin,” Sam explained I wanted wine. Our heroin was really wine. The waiter grinned broadly, handing us a wine list.

“Don’t touch me,” I told Sam, pointing my index finger. He’d reached for my kneecap.

“Touched by accident,” he said, our hands colliding. I noticed how handsome Sam looked. I felt the familiar tug in my bosom of how much I liked his company, how irresistible he had been to me since teenhood. My wooden bistro chair slid closer to his. We conferred in our old pal conference mode. In front of my eyes, he changed into a young boy again, growing younger by the minute, filled with charm and gladness. He never was handsomer than he was right then. I touched the fabric of his trouser.

“Ouch,” said Sam, “a delayed reaction.”

When we returned to his apartment on Mott Street, door polish smeared his hands. I tenderly bathed them upstairs for him.

He had a red couch. I reclined tipsily across his lap. He put a pillow beneath me and murmured something about a “sweet spot.”

There came a knock at the door.

“Exterminator!”

I began shrieking and squealing.

“We have mice but we just feed them, don’t come in!” Sam yelled.

I jumped up and ran to the door and down the stairs. Sam walked me to a metro station on Houston Street. Sam and I kissed the kisses of human paradise back and forth. Sam is probably the best kisser in the whole world, I thought.

I’d told him about my mouse Rose Alba who lived inside my Harlem apartment’s closet with a giant water bug named Heathcliff. I had read to him an excerpt from my diary: chronicles of Rose Alba’s life. That’s why he told the exterminator we fed mice.

Diary (verbatim entries of actual happenings)

I have roses in my room. Drawings cover the walls. My window has a floor-length, honey-coloured silk organza curtain. Rose Alba awakened me with delicate squeaking. She likes for mommie to check on her in dead of night. And so mommie does.

‘Hey, Rose Alba, are you eating the banana?’

I tossed her a bit more banana, noting that the sweetness of the smell, banana being such a distinctive aroma, will be novel for her.

Today, I did a deep cleaning of Rose Alba’s room, which is my closet, empty except for her wee, residential, inner-city field mouse items. I swept the wooden floor and I gently mopped with a warm mixture of lavender Lysol. I was careful not to mix the solution too strong because a mouse’s sense of smell is likely to be highly developed. Then I placed down new play boxes for her (discarding the old ones).

She has about five boxes of assorted sizes. Rose Alba is especially partial to her saltine box and her sugar-package box. The boxes have differently shaped windows and doors that I cut out, and when I call her and open the closet door, Rose Alba hangs her plump little mouse-self out of a box window to gleefully see what mommie brings.

I take great care to vary her foodstuffs and to make her chamber fun. She also has a house made of hay. She sits inside the hay-shack and eats meals. Sometimes I pick fresh clover for Rose Alba. And a moment ago, before the banana, Rose Alba ate a tiny slice of grilled eggplant.

Let me investigate. Yes, there are exquisitely small and very narrow tooth marks already imprinted into the banana hunk. The only things so far that she has not liked are raw turnip and green olive (brine-soaked).

I shower Rose Alba with love and attention and try not to think about the day when I must move out of my sublet and Rose Alba will be left to fate.

Once, Rose Alba ate a juicy blackberry.

3 AM

My birthday. Three or 4 AM? Rose Alba wakes me with squeaking and digging noises against a cardboard runner at the base of the closet door that separates our chambers. I arise and go into the hall and subsequently the kitchen; I open the refrigerator and take out a carrot. I slice a mouse-sized chunk and then cut that down into four sticks. Back in my room, I open her door. I can’t recall what I have just said because I am so sleepy, but whatever it was, it was soothing and gentle.

Rose Alba is now crunching the carrot. This will keep her interested until dawn. I can hear her from my bed easily because I sleep just a few feet away from the closet door.

8:30 AM

Rose Alba is such a good girl and has also stayed up late (mice are nocturnal). Hearing her stir quietly in her boxes, I opened the door and gave her some Honey Bunches of Oats cereal (dry flakes) and she is eating them now very cutely. Rose Alba is dove grey, my favorite color, half the size of my thumb, with bursting, berry-like eyes and round ears. She has lily-fair fingers and toes and her tail is grey. Her ears are a transparent pink by candlelight and swivel alertly when I speak to her.

The electricity in my bedroom is almost always out, probably because mice chew the wires. Sometimes I place a candle in the doorway. Rose Alba tiptoes over to it and looks and looks; she won’t actually go right up to the candle. But it interests her.

8:00 PM

I inserted a stem of clover blossom into a window of Rose Alba’s hay house when I came back home from Columbia. I also had picked her some clover salad (just the leaves). When I opened the closet door to see if she had taken the blossom (she had!), Rose Alba was so excited that she jumped high into the air, then plopped down and lay there ravishingly before running like the wind over to her mouse hole. I laughed and gave her the clover leaves.

I made a heart-shaped paper sign that says ‘Rose Alba’ in Gothic calligraphy and taped it above her mouse house’s biggest hole in my closet wall.

11 PM

I write by dim candlelight. Rose Alba pulled back the closet door by opening the cardboard runner that closes the gap between the door and flooring. I was asleep. She got Heathcliff (my giant water bug who lives in the closet with Rose Alba) to come out with her into my chamber. Oh, yes. And I found them both across the room over at the radiator, giggling and making noises. They were hovering there together in their little escapade. And all this after I had cooked them a hearty supper of rutabaga and clover! I opened the closet door and Rose Alba regretfully went back inside. She is smart and naughty. She slowly pulls her rounded hocks up and over the door jam. Everything is a mountain to her small frame.

But poor Heathcliff is confused, not knowing what to do next. And I can’t catch him because he is so quick.

He at length did go into a crack in the floor at the wall beneath the radiator. I taped this over with masking tape. Dear Heathcliff son (I call him my little son) is a voracious eater. He devours noisily saltine crackers and cake. If he were in my bedroom, he would run around savaging everything. Rose Alba was very naughty to lure out little Heathcliff.

Afternoon

Infiltration Alert! Chamber Breach!

Coming back from Columbia, upon early afternoon re-entry into my chamber, I see Rose Alba running everywhere, looking at everything in my bedroom. Good grief! She has done this shocking thing after I left for school. AND she is supposed to be nocturnal.

Then I look at the closet door: a tiny hole, 3/4 the size of a dime, is circularly incised into the cardboard runner. I open the door. Heathcliff sits placidly inside his play box (the sugar box), toying with a few seeds.

I told Sam I was going to write my memoir to include a concordia of Rose Alba diary entries to go along with the main text. He said he wanted to give my memoir to his literary agent, David Kuhn: “This could be a really big deal, Alison, if you’re willing.” But I said I wanted to navigate clear of commercialism in Art. I wanted always truth. My candor seemed to worry Sam, but I knew not why. “You’re the most un-hiding person I know,” he said.

I came from great wealth in life. I knew the value of money was zero compared to sentiment and honour. I wanted Sam, not coins.

Happiness drenched us both with glee every time we saw one another and I introduced Sam everywhere as my fiancé after we were officially engaged. Columbia Security eyed him with surprise (they’d never seen me involved with a male). “Good choice!” a guard exclaimed (a good choice choosing me). The comment pleased Sam. We both felt lucky.

These were the happiest days of my life, kissing Sam. We spent one whole summer in Heaven.

Sam sent an army of emails, making always a next plan when he broke our original plans to meet: Oh Alison, please don’t torture thyself (as I try not to torture my own silly self with my unconquerable desire for your raven haired girlhood). Love will conquer all our fears. S

Bringing me forth from Butler to walk among blue hydrangea, he sometimes arrived hot on the heels of his various magazine assignments. We toured my favorite campus gardens, accompanied by birds and birdsong. In the Art History building, Sam wanted to use a restroom. A Men’s Room adjoined a Ladies’ where I stood dawdling at a sink and mirror. He rushed inside. “I can’t go in there, Alison. Someone’s doing something bad.” (An administrator told me later they eventually had to put a lock on the Men’s Room door because people kept doing for illicit acts and drilling holes in the stalls.)

Sam used a toilet inside one of the ladies stalls and I washed his hands. I explained to Sam that this was the same restroom where I’d brought my campus dove Lambish after she was poisoned: I washed her beak at this self-same sink before carrying her in my arms all the way to the Lower East Side where they had given Lambish a “save shot,” hydrating her.

Sam sat with me beneath a Columbia flagpole and we watched clouds, talking. Lambish had died two years earlier, but my black and white dove Gigi was sitting on my knee. I fed Gigi seeds by hand and Sam picked up the extras as they fell onto my skirt. His leg was touching mine.

On another date, I wrote, “I love you” in crayon on the back of his bread plate while he was in the restroom at a restaurant that had padded, red couches. “A Picasso,” Sam said, holding the bread plate in his hand to read my message.

Over goodbyes, he smelled my scarf. I wished it were something more luxuriant for him, perhaps from the ancient time of Egyptian pharaohs, woven for the Ptolemies. “Allen would be proud of you,” I told Sam, “That you write for a magazine.”

But he seemed troubled, “I’m not so sure.” Dearest Sam, always under-confident and always the best ever. I wished I could fill his heart with the same bold confidence I have by nature. And for a time, my love seemed to do just that.

On a subway platform outside the black iron gates of Columbia, a train pulled in and Sam was about to board. He was going back to Mott Street. I threw my arms around my sweetheart and kissed his lips with ardent enthusiasm. He opened my mouth with his tongue. We kissed with all the passion in our artist-souls. Each kiss with Sam was worth a lifetime to me. Married people might have more time together than Sam and I did during our early engagement, but we definitely got the better deal, I believed. A treasure never to be stolen away.

I jumped inside the subway car with Sam and we continued kissing. It took a few train stops before we parted bodies. “So spontaneous,” Sam said, wistfully.

“Are you sure you don’t have a girlfriend, Sam? Isn’t there anyone else? I don’t want to come between any commitments you may have.”

“There was someone, but not now. And who would want them when they could have you?”

He spoke about an intense ‘homosexual culture’ at his magazine and many of our teachers at Naropa had been gay men. It would be fine with me if he preferred a man’s love to mine. I wanted his happiness to be as complete as he’d already made mine so I asked, “Are you gay?”

“No, but they think I am at work.” he said, “It’s how I got the job.” All that mattered to me was that in my arms, my sweetheart was happy. He was valiantly hurtling through life’s most rigorous trials by being a writer in Manhattan media. I hoped to make his life easier, not harder.

We decided to have a night of pre-honeymoon delight. I was going to wear my clothes and he was going to wear a bathing suit? He fished one out of his closet that was ridiculously tight. Dark blue. A torture device. I hated it. I thought they’d given the swim trunks to Sam at some horrible Hollywood party where older, corpulent men try to corrupt young people. Sam would never select a bathing suit like that one. He didn’t even like to sunbathe. I asked him to take it off. I carefully didn’t touch any of the male portions, but I cuddled him very much and with lots of kisses. Beautiful Sam was naked in bed with me. He drifted into sleep, but I stayed awake all night in the happiness of being next to him. He was the green heart inside the center of the fairest pale rose. He teased me that I was “Un-sleeping Beauty.”

This was the best night of my whole life.

First, we had revisited the bistro that had Brazilian soap and walked hand-in-hand to the edge of the East River to see the sun fall below the horizon and turn the water into an egg yolk.

We were then in bed for our first overnighter and I wore a ripped, pink Columbia tank top and a pair of underpants. Luckily, I had the underpants. I’d just had my period. Normally, I didn’t wear underpants. Sam was now my officially betrothed beloved and I was come to claim his kisses.

Sam: “Tupelo Honey.”

Alison: “Too below.”

He pulled my honeybee patterned panties up and down like window shades or people’s socks rolling up and down in old 1920’s and 30’s comedy skits, like in the Little Rascals.

Sam: “Spanky, Alfalfa and Buckwheat!”

Alison: “Delilah and Butch the bully!”

Sam: “Nobody ever says Butch’s name, but you did!”

Alison: “Delilah, no, Darla. Her name was Darla, not Delilah; I named one of my squirrels at Columbia, Darla.”

Sam: “This (bed) can be our clubhouse, a clubhouse of bliss.”

Alison: “People do this on their honeymoon and we aren’t there yet.” His hands wandered and caressed. He didn’t notice he was pulling down my honeybee panties. When I pointed it out, he yanked them up way too high. He said that what he was trying to do was to staple my panties to my tank top to keep my clothing together. But then his hands started to graze coltishly beneath my tank top. I pointed that out, too, so he could staple everything together again. Sam said my cotton honeybee panties were fresh and sweet, much better than lace panties. The magic was that we loved each other—deeply, permanently, enthrallingly loved one another, and had since youth.

Alison: “Do you like apricots?”

Sam: “Yes, dates, apricots, figs, and olives.” We liked the Middle Eastern foods of ancient Israel.

Alison: “When I was a little girl, I used to eat straight through the cob of an ear of corn unless somebody moved me down further along,” kissing his kneecaps.

Sam: “The miracle cure,” for his knee got bumped in a taxi when last visiting me on campus at Columbia.

Alison: “You can feel all of my ribs.” He was doing that anyway.

Sam: “I know. Here, you can feel some of mine.” I did. His body hair was soft, especially beneath his arms.

Alison: “Silky. Silky-silk. Silk-worm.”

Sam: “Bzzzzzt!” He touched my honeybee panties before slumbering. I couldn’t sleep because he was so exquisite to behold. I went into Dovecote’s bathroom and squealed with delight to God, “Dad! He is so beautiful! Thank you so much!” Then I ran back and kissed my darlingest awake. I always felt that God was my Dad. But I loved Sam now more than Dad.

Alison: “I am in bed with the Seussian!”

Sam: “Jakob with a K.” Jakob, his middle name (They misspelled it “Jacob” on his Naropa poetics certificate), “Being engaged to you is going to be sweet and fun.”

We spoke in bed about Naropa. Ginsberg had admired the poetry of Robert Burns (namesake of my birth father) and once took Sam on a pilgrimage to Scotland, the land of my Campbell and Burns ancestors. Sam recounted how he and Ginsberg stopped inside a Scottish bookstore and discovered a Jewish prayer torn from a book. It embarrassed Sam, but Ginsberg searched through every volume, until he found the one with the missing page, and replaced the prayer. It took a long time. But Allen Ginsberg would not relent, Sam recounted.

Overcome with emotion, Sam told me he didn’t believe in God, “But I envy those who do.”

Sam and Allen Ginsberg loved each other. Those days at Naropa were irreplaceable to my betrothed’s heart and psyche. And to mine, too.

Alison: “What’s that street Allen lived on?” I asked, my mind a blank from Sam’s many kisses.

Sam: “Mapleton.”

“Yeah,” I said, “Mapleton Avenue.”

“I want to make love to you,” Sam said in the dark. I fell silent; we weren’t yet married. He didn’t insist. I was happy he said it, though. And when we married, I planned to make lots and lots of love.

I watched him sleep, my arm over his shoulder, kissing him ever and anon. When he woke, we walked to Balthazar restaurant for coffee because it was the only place open. I kissed his fingers when he messed them with berry jam. We told each other things that had recently transpired to wound us. I was not long out of graduate school, where I’d been bullied relentlessly. Sam said he’d been bullied at his magazine. Homosexual harrassment, he said, “But it’s better now.”

“It isn’t very fun to be sexually harrassed all the time,” I said. I think we were both targets because we stood out from other people and exuded a sort of irresistible attraction to people.

After croissants and jam, we shopped for my wedding gown and I took a shopkeeper’s card; we needed to make an appointment to try on gowns. An appointment Sam did not keep. His magazine sent him on an assignment. He was called away to write a cover feature on Marilyn Monroe.

When Sam was free, we were merry, but with his increasing obligations, Love’s horizon darkened. He said his former spouse reappeared after he co-authored with her on a book that suddenly hit a bestseller list on the New York Times. Sam said he’d done most of the writing but wanted to be kind. He began to say that he had to earn more and more money to be of use to his aged mother and the “ex-wife!” And he disappeared again and again.

“Darlingest, thou overthinking geniusgirl of my lifetime. I do have a sense of urgency about this, it is just we need the patience of the saint I think you might be to get us through this difficult time of my book and the demands of this weird job I have fallen into,” Sam told me.

Our future on hold, I resumed my job at a non-profit, commuting to Queens. Sam said he was selfish, but I must return to him and leave my job. He’d write me into his magazine budget as a researcher. That never happened but he began passing me assignments and I did research from inside Butler Library; I was renting a room with graduate students near Columbia. I did lots of research, whatever he asked, about River Phoenix, John ‘Duke’ Wayne, and Mohammed Ali. Sam began calling me “Mohammed Alison.” I was a hotshot NASA researcher, highly skilled, and my teachers from Naropa had all been literary gods.

Sam and I made a fierce writing duo, but it was not to be. While he was away, I read that he was actually married, that his current book promotion was for Sam and wife.

Shocked, I sent him a message that we must never see each other again. My heart was slain, if Sam was really married. I started having Ophelia-esque tantrums, said I would return to the cloister and never speak to him again.

Emailing me from afar, Sam dissolved my fretting:

Alison, will you do me this last act of kindness and let me know how I have proven false to thee? Do I have any right to know why we are not to see each other again? If this has anything to do with my book/ or how it was written/or with whom/I hope that is not why we must part darlingest Alison. Because you shouldn’t believe what you read or what people tell you/or heaven forbid get something off the Internet which is a fount of mis-information. I am very safely and legally divorced from N. who I applaud for putting herself through the promoting of this book despite our years apart and her living in the Dominican Republic where she will be running a hospital and living as a good sister, which has always been her dream, and not married life. So if you read or heard somewhere that I was married, darling Alison, that is someone relying on very old news. I just didn’t want you throwing the baby out w/its bathwater, without knowing the facts. I was lied to once/about my grandfather/they told me he was coming home from the hospital/he never did/I cried and moped for days/ weeks/I never forgot it/I would never bear false witness/I would never never be false to thee and abuse your trust/and darlingirl I would never ever harm you/and to lie (and to lie about such a thing) is harmful and cruel. I am also, terribly old-fashioned/and faithful, I am like a duck/I mate for life. I would have had a hard time simply holding your hand crossing the street if I were spoken for. So a kiss, which certainly means much more, was surely the signature of my faithfulness to you and my true status as husband to your future.

Sam emailed:

I adore you Alison/and have many thoughts of a sweet future with you/I only plead for your patience/they are sending me on an assignment this afternoon directly from work/to Conn. I may have to be there for a few days/impossible to get out of. See what I mean? Please wait for me/and PS I have ordered my budget for River which includes your salary in full/it should come through in about a week. Love, S

He wrote:

Dhalinka, if they don’t send me w/a boss man to Conn then I will make a beeline for the flower in your hair. Otherwise I will walk around with my heart in my mouth until we are killing a vial of your beloved laudanum together. Yes, more River less Duke. Compile that list, a towering list of people to interview. Love and violent hugs, S

It’s like we were back being kids on the floor together at the feet of Trungpa Rinpoche, writing notes and passing them to each other in our journals. And anything Sam said to me, I believed on a bed of clover.

I creatively composed boudoir lunches as email descriptions to send Sam, imagining serving him and I waited.

He said it was better to talk about things in person and he would soon return. A sample menu of the many I sent via email:

Dearest, since you domicile in Elsinore and I am trapped in Gotham, I send you the heartiest fare that I can so that you keep hale. Wear the sable. I shall sleep next thee naked every night until you come home (to keep you warm). Chaste, but naked. Well, likely with a lot of passionate embraces and kisses. Anyway, I write to send thee dinner. I am serving it whenever you are hungry today or tonight. First, you must be seated comfortably and in a warm room. Just go ahead and eat in my heart’s boudoir because I will make a fire for you there at all hours of the day and night. So make yourself at home. And we will sleep in front of a fire, beneath sable. I roasted a swan for thee. The skin is succulent and crispy, the flesh dark and savoury, rubbed with white pepper and ginger root. I mixed swan giblets into gravy and I spoon this over your bread spiced with rosemary. You had best have a bit of wine, darling, since it is cold outside. We are only having the roasted meat, the bread with gravy and a dessert, which is a cherry pudding with flowers stuck into the pudding that you can pull out one by one. The recipe is medieval: For to make Cherries, take cherries at the feast of Saint John the Baptist, & do away the stones. Grind them in a mortar, and after rub them well in a sieve so that the juice be well coming out; & do then in a pot and do there-in fair grease or butter & bread of wastel minced, & of sugar a good part, & a portion of wine. And when it is well cooked & dressed in dishes, stick there-in clove flowers & strew there-on sugar. Well, darling. This is all that I can do for you until you return to me. I shall check with thee tomorrow. It is cold also here and I run out to feed my doves at Columbia in the mist and light, but chill, rain. I run to my rented chamber to think of you and to read Jane Eyre. But I sleep next thee and soothe thee ever a betrothed can. Alice

Of all the names Sam had ever called me, my favourite was Alice. I sign my paintings ‘Alice.’

Sam assured me:

My meal was sweetest fare made by an angel for an undeserving cur. You must divine how I love thee/the word that is beautiful in all languages. Your good nature is a consolation in all events, big and small. Don’t think less of me for being so absent. I think of you though Alps and Ocean divide us, but they never will, unless you wish it.

I believed in Sam. Whatever he said or did made me happy. I began to send him long love poems. Our days and nights held hostage by his work commitments, I resolved to attempt patience, a virtue I’d never possessed.

And then bang, a shot through the heart. Sam came home to me.

We met at Dovecote on Mott Street.

The first time I touched Sam naked, I screamed with glee. A magazine editor named Graydon Carter kept calling my sweetheart’s cell phone. Over and over again, and Sam wouldn’t pick up. Why was that?

We were just going to look at everything. I’d given Sam the Cartier engagement ring he asked me to buy, 18 karat. I wanted to purchase china for our apartment after our wedding, but Sam said he’d rather have the ring, a rose gold band. And it was on his finger.

I unbuttoned his pants.

Inside there was a really handsome item all golden. “It gets even bigger,” he said. Right. Incredible. I named this being Helen, for my sweetheart’s beauty launched all ships to sea more grandly than Helen of Troy. Helen was the beauty of the ancient and now modern world. I was seated at Sam’s glass-topped dining table. On a stool. Holding Helen.

I held the golden item in my hand. I delightfully examined every feature: “Is this circumcised or uncircumcised?”

“Circumcised.” Sam said Helen was circumcised. I was ear-to-ear smiles with girlish gusto. I saw a little rim of circumcision. I had never before held a cock.

Sam said he had to depart. A taxi was waiting, what? He needed to leave immediately on a trip orchestrated by Graydon Carter, who Sam said was always threatening to fire him. His cell phone rang non-stop while Sam kissed me passionately. He gripped the back of my hair in a tightened fist. Sam was impressively strong. He picked up my left leg, holding my thigh in his palm. He pulled against him more closely. The cloth of my Victorian gown was voluminous and accommodated easily my new stance. Sam surprised me with so much fire and might. I showed him myself, too, pulling up my gown, cautiously. I wore no panties. He could see the raven curls, but just for a second. He smiled.

With input from Sam, I had arranged for a formal Catholic, and also a sacred Jewish, betrothal ceremony but all that went out of my head. There was no time to talk about anything but loverly love. We left Dovecote, regretfully. In a taxi, I kept my hand right there at the point of exodus. The point of no return. The breaking point. The point that I was making was about Helen. This was my one and only time in life to have a lover, the exact boy of my dreams and we planned to wed. Instead, we were speeding to Graydon Carter’s Upper East Side apartment, then Sam and I were kissing at the cab’s window, and I had to race onward without him in the taxi to Columbia. He ran off with a small valise in his hand as a light changed as the taxi zoomed away with me marooned inside.

We arranged for me to stay at Dovecote, using an extra key suspended from a tiny version of the Eiffel Tower in Paris. I was to await his quick return. (But Jake Seuss postponed.) While I was there alone, I saw at Dovecote an 8 x 10 black and white glossy of Graydon Carter without any clothes. And the photograph worried me. His pose in an open doorway and his vacant facial expression somehow seemed sinister, and at least, very disorienting, to my near newlywed maiden sensibilities. I fled back to Butler. Graydon Carter, whom I met only once, perchance did not yet know his magazine, and very self, kept pushing into my private life with the boy poetic, Sam Jake Seuss.

All seemed more and more mysterious, but Sam made me happy. I wore my Dovecote key, tied to a red satin ribbon. Sam said a married woman was coming to Dovecote in order to ‘homestead’ and we must again wait. While he was away, I sent him love poems and boudoir meals from Columbia University. He sent me love notes.

Since my godmothers were both dead, I began to ask feminine advice from Jeannie Campbell’s ex-sister-in-law, Georgie Ziadie (Lady Colin Campbell). Georgie had married Jeannie’s youngest brother, Colin. We’d never met in person because Georgie lived in Paris and London, divorced from Colin, before Jeannie and I lived in Rome; Georgie had long been out of my extended family’s sphere. But she was the one I contacted to guide me.

Georgie wrote Sam a letter, welcoming him and congratulating us on our engagement. She sent the letter to Sam at his magazine, Vanity Fair. He said send it there because someone was homesteading at the Mott Street apartment.

I wrote to my former research leader at the Jet Propulsion Lab, asking if Sam and I could visit JPL for our honeymoon. Sam said a visit to JPL was his boyhood dream. Security was tight at JPL, a strict process involved to obtain a visitor’s permit. I asked how much notice I needed to give, knowing how uncertain plans were with Sam. My JPL research leader said that in my case, I could give almost no notice: “One day.”

Sam wrote an email to me that Georgie could send our wedding present to our hotel in Los Angeles when we arrived there to honeymoon. He was trying, but there was much more going on than I knew. All I wanted was to have our sweetheart life together, but his professional career entangled a seemingly endless chain of obligations. “Fetters,” said Sam. Another problem was that he did not tell anyone about my research for him and his secrecy created confusion. “Because I can’t,” Sam said. He told me despair was unworthy of me and I shouldn’t fret like Hamlet’s Ophelia.

In distress, I decided to visit writer Anthony Haden-Guest, a family friend and close pal of Jeannie’s brother Lord Colin Campbell. Haden-Guest had written for Vanity Fair before Graydon Carter took over as editor-in-chief. I thought perhaps Anthony would have good advice for me. The publishing world Sam inhabited seemed not the sweet-spirited, poetic world of writing I knew from JKS. I would need a paying writing job, if I was going to wait long-term for the return of Sam. I had applied to the New York Academy of Art’s MFA program, but by the time that school’s director emailed me to discuss a spot in their program, I ignored the offer, being then in the throes of wedding preparations to Sam.

The 2008 economic recession continued to blanket America. Writers went unpaid and jobs were scarce. I was in a precarious position.

I turned to Anthony Haden-Guest for guidance. Surely, he would know what to make of my mysterious engagement?

Thirty years ago, Anthony Haden-Guest had lived in Rome, in the heart of the old part of the city, a friend my godmother Jeannie Campbell. Jeannie’s grandfather, Lord Beaverbrook, once owned the Daily Express newspaper, the London Evening Standard and the Sunday Express. She married author Norman Mailer in 1962, divorcing a year later in Mexico; Jeannie was Norman’s third wife. Haden-Guest knew all; he was a person in whom I could confide. He said come straight away to Manhattan’s East Village, where he lived, and we met at Sheridan Square.

To sit in Sheridan Square unnerved me. Sheridan Square was dirty; bench surfaces, questionable. My long skirt trailed over everything: sputum, trash, thrown-down stuff and possibly lurking bedbugs. Haden-Guest put me at my ease, something to do with the way his eyes crinkled when regarding me.

Anthony smiled in the same way that Jeannie used to smile, a Cheshire sort of grin, really, fit for an Alice. In my eyes, Anthony was all wrapped up in people associated with my past, as if he’d been packed away in tissue paper and I was taking him out carefully for inspection, mesmerized that he even existed. I listened closely to what he said: “There was a long moment of infatuation between Eastern mysticism and Western culture and you were there.”

Anthony and I sat in sunlight. He interrupted our conversation several times to check on a scuffle a few feet away at a bench across from ours. Drug addicts, too weakened to properly choke one another, placed hands at each other’s throats, staggering to their feet in ineffectual disagreement.

Anthony wanted to hear about Allen Ginsberg and the Beat poets, how I studied with them at Naropa, and what I thought about it all as a teenage girl. Jeannie Campbell had been interested in the Beat poets, but had never met them in life, although Norman Mailer knew Ginsberg. Anthony had known Mailer but never met Ginsberg.

Anthony had a strong sense of what it meant to be gallant, right up there with A Tale of Two Cities. It was why I instinctively loved Anthony. He appreciated the finer things in life. I had sought him out because he was the only person I knew still living who like me, could sit with a pot of hot water rather than confess to a lack of tea. We possessed a sense of noblesse oblige, a sense of caring. Ownership of our actions.

Anthony wanted to know about William Burroughs. “Old gashes” was how Burroughs described elderly women in his books. Burroughs wore dark suits and wide ties. He would sit at his table in a kitchen, a folded newspaper in front of him, his face introspectively handsome, but eroded over time by drug use and hard living. On the stove sat inexpensive cookware: tin pots plated with white enamel and an old fashioned coffee maker with a handle and pouring spout. A towel draped over a radiator, and a trash can of paper bag. Teacups on one shelf, bowls above. Spartan.

As I spoke with Haden-Guest, Sheridan Square drug users began to strangle each other again, making feeble attempts to stand. A tall man rushed up, leaning over our bench: to Haden-Guest, “Do you have a cigarette?”

“No, I don’t smoke,” he replied.

“I’ve got to get a cigarette!” The man was urgent. Haden Guest’s answer to the demand of a cigarette was given in a tone of gentle thoughtfulness I admired.

People have called him a bon vivant. “Bon vivant,” Haden-Guest shook his head, “is just another way of saying an alcoholic. And I have never thought of myself as an alcoholic.”

He had authored a book about 1970s disco Studio 54. Diana Ross, Sylvester Stallone, Jack Nicholson, and Ryan O’Neal were some of the stars of the disco era and they all frolicked at Studio 54. Ian Schrager opened Studio 54 in 1977 with school friend, Steve Rubell: Glitter and opulence strewn across a floor, filling people’s socks and hair. Mick Jagger’s wife Bianca rode into that club on a white horse.

Mayhap it’s easy to be nostalgic about distant years, but they seemed innocent. Studio 54 was found stuffed with cash, in the walls, ceilings, and basement; Steve Rubell ultimately arrested driving a Mercedes, with 100,000 USD in the trunk and more dollars crammed behind bookshelves in a Manhattan apartment, so much money that there wasn’t space vast enough to stash it all, but to what purpose? More nights and more Quaaludes, everyone trying to enter the nightclub, past a velvet rope at the door, into the drugs and dance and fraternization that was Studio 54 in its heyday. Michael Jackson had been there, wearing a giant Afro and grinning like a kid. He was a kid. Steve Rubell died of AIDS.

Anthony Haden-Guest’s younger brother married actor Tony Curtis’ daughter, Jamie Lee, who starred in John Carpenter’s Halloween.

I asked about life, what I should do, and what the mysteries behind my betrothal might indicate. Haden-Guest spilled the beans on big-name editors. I learned that New York publishing was a corrupt-sounding place I did not understand. He offered to introduce me to an editor at Huffington Post. Only problem was, my articles would be unpaid. He said not to wait for Sam. I did not take his advice.

The fatalistic shove into homelessness came when Sam, a year and a half after our first overnight together in Dovecote’s bedroom, began striking me. We were both naked; I was reclined, worshiping him and making love over and over again.

Without a word: physical violence.

The next morning, on a small mantle at Dovecote ‘twixt kitchenette and bedroom, I saw to my chagrin, a 5 x 7 black and white glossy of my sweetheart in the same pose I’d seen of Graydon Carter many months before.

Right after he hit me, he’d sent an email, “I’m glad you are such a good soldier.” I thought I carried his baby, but I was only injured. I said he couldn’t hit me again because he might kill me like Fatty Arbuckle in Old Hollywood lore.

“I feel so guilty,” he said.

“You are not guilty!” I insisted. I never stopped loving or waiting for him, but Sam failed to foresee that nearly killing his lady would have an adverse effect. Yes, I reported the assault to the NYPD. A girl has an obligation to go on record about violence against women, even if it is her beloved who gets violent. No, I did not press charges. Yes, I forgave him instantly. The moment it happened, even as it was happening. But yes, it all left me totally confused.

I had no understanding when he began spreading falsehoods about our betrothal: “It breaks my heart to hear you cry, but I know how these (publishing) men think,” Sam said. He forwarded to me an email he sent, slandering me, personally and professionally. Aghast, but ever trustful of my sweetheart, I let the slings and shots of worldliness rain down upon my head of raven hair and tender thoughts for two years of homelessness.

Meanwhile, I wrote a slew of unpaid Huffington Post articles. I covered art openings, wrote book reviews and interviewed scientists. Sleep-deprivation and homelessness lent my articles a breathless quality. The first article was about Amy Winehouse and Marilyn Monroe.

Winehouse’s designer (of Amy’s beehive hair-do “Blake” heart) sent me a puffed, red leather heart stitched with my sweetheart’s name, in gratitude for naming her in the Huffington Post article. She sent the heart from London: the heart’s white banner read in black letters, “SAM.”

Homeless inside Butler Library, one evening I found an unexpected book: Sex Matters for Women. I looked at the diagrams, hand-drawn and printed. I read about the Cowper’s gland. I read that semen contained fructose syrup: fructose to nourish sperm. Unable to live at body temperature, sperm perished unless cool. And they swam.

Another year passed. I read in Vogue magazine that Sam was married and never divorced.

Sam was like one of those boys I had read about in literature.

“Mad, bad, and dangerous to know” was a famous description of poet Lord Byron, the most dazzling and notorious of the Romantics.

For talent, beauty, chaotic tumult, and personality, Sam outstripped Shelley, Keats, Blake, Wordsworth, and Byron.

“I would love you even if you were ninety years old,” I had told him one balmy afternoon, early in our betrothal, as we walked along a hedge of Columbia’s blue hydrangea bushes that buzzed with bees. Sam was everything to me and utterly without peer. I loved this one boy, and took it as my womanly luxury in gratefulness of heart: hero Sam Jake Seuss thrown my way. But the boy was also killing me.

12. Homeless Newsreel

(Unlit Desertion)

On Thursdays, the student center on campus is open until three in the morning. With Butler closed, from 3 until 6 AM, I must ride the subway. And on Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, the student center closes at one so I’ve got to ride the subway for an additional two hours, unless I choose not to exit Butler Library.

My toes are frost-nipped. Brown rats the size of ship dwellers run through the 14th Street station, gamboling all over a “‘Number 1” train platform. Peels of reckless mirth: rats squeaking with happiness, running everywhere, seizing tidbits, while I cower at the top of an exit stair until a train arrives.

“I’ve got it right here. Here, Lenny.” A man scratches his head at lice as a woman speaks, “This is the schedule. For all of the trains,” says his homeless partner, her head covered with a cap. They wear thin clothes. Outside, nineteen degrees Fahrenheit. The subway platforms are freezing cold.

“Good evening ladies and gentlemen, my name is Chris and I am homeless. I am a United States Marine and I fought in the Gulf War.” Chris wears matted dreadlocks. He seems polite, in that he skirts clear of the womenfolk on the platform and train, instead of getting in our faces and scaring us.

“Loco!” screams an old woman.

She looks sweet. Aged. Carrying two enormous bags and suitcases. A young Latin male tries to help her down some steps. Big mistake. The old woman morphs into a banshee: “Leave me alone!”

“Da mi la roba,” the Latin male says (give me the things), still trying to hold a door for her. She screams for the police and shouts abuse, in Spanish and English, “I am Mexicana! He saw me there! Leave me alone! Polizia!”

I say to another girl at the station, “He was just trying to help her with her bags.”

“I know,” she smiles at me, “I know.”

Two young men kiss nervously aboard the train. Their combat boots are lace-less.

As soon as it is 6 AM, I can go to Starbucks. The student center at Columbia opens at 8 AM and I can come in out of the snow.

These are my nightly adventures in homelessness aboard the number 1 and 2 trains on the Upper West Side or at most, from 125th to 14th Streets. I dare not go below 14th Street at 4 AM. A Jack the Ripper could be in Rector Street, for all I know. At the very least, it would be a place of unlit desertion.

It is torturous to walk in the subway and remain vigilant overnight.

I see intoxicated Columbia students, usually girls.

Addicts and criminals are everywhere. It’s like being in Victorian England’s horrid White Chapel district. But I am waiting for Sam and I am super strong.

13. Frank Sinatra and the Concrete Kings

(Zebra)

Reader Road Map: Winter 2015/16. Current Events: Extreme weather has people running scared; seventy-two degrees on Christmas Day in New York’s Hudson Valley; below freezing just after New Year’s Eve. News Topic: racial protests.

“It’s a pain in the ass!” Ralphie Valente said to me about the weather, driving up last holiday season to visit my studio in Kingston on the waterfront. His business partner Frankie owned the building. I greeted Ralphie and Frankie with a good-hearted, daughterly smile. I treated both like family for as long as I knew them.

Frankie would not stop asking me to “get physical” with him so we all stopped being friends. “I’d rather be dead,” I told Frankie, and he got really angry. But at first they were both nice to me and I asked them a tonnage of questions about the old days of the Rat Pack.

Eighty-one, Ralphie continued working, overseeing properties and deals; he told me he used to own nightclubs, and that when he was a little boy, he’d shined shoes for Murder Incorporated.

Ralphie said he gave actor Joe Pesci a bouncer job before Pesci hit the big time in Raging Bull. Ralphie knew all the big Hollywood players when they were young, from Barbara Streisand to Tom Cruise and Al Pacino. Ralphie was the younger brother of Fox Valente, Frank Sinatra’s upstate New York bodyguard in the 1960’s, along with Jilly Rizzo. Rizzo died in a 1992 car crash, slammed by a drunk driver in Rancho Mirage, California.

“He cried,” Ralphie said Fox told him: “All my pals are gone, Fox.” Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Ava Gardner, entertainers, club owners, Mob bosses, and girlfriends. Life is like that, you lose your friends.

Ralphie was born in Naples, an Italian like Sinatra.

Ralphie delighted me with his memories of Las Vegas, Manhattan, and the Rat Pack: “After Bogart died, Sinatra took out Lauren Bacall.” Sinatra was big on protecting women when their men died. Jackie Kennedy went out publicly after JFK was shot, squired by Sinatra.

“He walked in with her at the Rainbow Room in New York,” Ralphie remembered, “Nobody interfered.”

“Bogart came to the El Morocco, one night in the middle of a week, late 1950’s, the club half-full,” Ralphie said he sat at a table with his big brother, Fox.

Humphrey Bogart had on a black suit: “Shirt and tie. Sharp. He looked like a racketeer. He looked like a gangster—some gangsters didn’t even look like that. Bogart was everything. He stopped a room when he walked inside.”

“The El Morocco was a meeting place for the entertainment world. Tables against a backdrop of curtains. Very Casablanca, like the film. The food wasn’t that great. You’d see the same people, maybe, but the atmosphere was less stuffy than at 21.”

“The banquettes were all made of zebra skin. It was a private nightclub. You had to be a member. Princess Grace, everybody went there.”

“If you went to 21 Club and you were rich, a Rockefeller or Whitney, you would be catered to, but if you were a regular Joe, you’d get to the back of the line and hope and wish you got a table.”

“Men wore suits. Ties. Always a jacket. Unless you were Bogart, and he could come in anywhere with a jacket and open shirt collar. People respected Bogart. Liked him.”

“The menu at these places was pretty much steak and fish, with a few specialties. Not too much lobster tails. It was sirloins and porterhouse. Bass and fish filets. Maybe you’d see Veal Sorrentino with eggplant.”

“Drinks were the big thing back then. Men, to start out the first drink of the night ordered one of two things—a dry martini or a Manhattan, usually rye and sweet Vermouth. Ladies ordered Old Fashioneds. Fruit with a big cherry inside.”

“Sixteen times, a good-bartender stirred a drink. Never shaken. Always stirred.” Ralphie leaned back in a chair with his feet up, talking, and I made him coffee. “Nobody bothered the famous in the old clubs. It wasn’t done. Sinatra’s favorite restaurants back then were Separate Tables (he was good friends with the owner), Patsy’s on 58th Street and over on 2nd Avenue, Rocky Lee’s. Rocky Lee sounds like a Chinese place, but it was Vinnie Panetta’s. Clubs kept tables for Sinatra where nobody else was ever seated.”

“Vending machines were big money. A pack of cigarettes cost 28 cents. And your refund from a quarter and a nickel was 2 copper pennies tucked inside the cellophane. Pall Mall. Lucky Strike. Philip Morris and Chesterfields. Old Gold. You bought one cigarette, a penny apiece.”

“What kind did you smoke, Ralphie?” I wanted to know.

“Chesterfields. Then Kent. Kent had filters. One night, we’d been at Separate Tables. Food was outrageous there, especially Veal Scallopini,” Ralphie said. “Then we decided to go to Jilly’s bar.”

“My brother Fox drove a silver Lincoln Continental, late 60’s model, and Frank Sinatra followed in a limo. Sinatra bet Fox a bottle of champagne who could get to Jilly’s first.”

“You got a bet,” Fox said.

“It was about one in the morning,” Ralphie described, “Fox was way ahead.”

“Sinatra reaches in the glove compartment and pulls out a .38 handgun, laughing. ‘I blew the Fox’s tires out,’ he says, walking in the door at Jilly’s.”

“Who did Frank Sinatra love the most?” I asked.

“From the old days? Dino (Dean Martin). “And he was close to Sammy (Davis). He was crazy in love with Ava Gardner, even though they fought like cats and dogs. He was close to actor Peter Lawford and Jilly Rizzo. Jilly had hired Frank in New Jersey early in his career and after Sinatra made it big, Jilly was his bodyguard.”

Ralphie thought a moment and added, “Sinatra was real close to his first wife. His social life changed, when he married her.”

“What about Vegas, Ralphie?” questioned I.

“Women weren’t allowed in Vegas in those days. Only hookers.”

“But couldn’t Frank take his wife when he performed?”

“Don’t worry, Sinatra had plenty. The prostitutes were gorgeous. ‘Hey Fox, go downstairs and get me some girls,’ Frank would tell my brother.”

Ralphie was at a table with Fox when Sinatra recorded Live at the Sands with Count Basie in 1966 at the Copa Room. Sinatra introduced “Luck Be A Lady,” a production song from Guys and Dolls with a roll of his hand, “It’s a story about a pair of dice.”

“Sinatra’s first wife never remarried,” Ralphie sighed, “and she never said anything bad about him.” She didn’t want anybody but him.

Frankie began telling me about his old friend Biff Halloran. Biff was nicknamed the ‘Concrete King.’ Like Jimmy Hoffa (vanished Teamster Union boss), Biff went missing. Something about a mafia boss and the way Biff treated his daughter.

Frankie said Biff’s disappearance was in all the papers. He controlled concrete sales in Manhattan construction with an exclusive monopoly and owned a swank hotel on Lexington Avenue. “He was an early Donald Trump,” Frankie said.

“People support Trump’s bid for the Presidency because he will run the White House like a business,” Frankie nodded.

Frankie said he planned to vote for Trump in the 2016 Presidential Elections: “America is a business.”

Frankie should know. He owned vast real estate: clubs, restaurants, stables, golf courses, residential and commercial properties up and down the East Coast. Hillary Clinton tried to rent one of his houses.

“Biff,” Ralphie flicks the name. “He was a friend of mine and very popular. I was thinking about him last night. I saw on television a story about a diplomat visiting New York, staying at a hotel.” The hotel setting reminded Ralphie of Halloran House Hotel (currently owned by Marriott). “A maid comes in and the diplomat is kind of naked, you know, because he just got out of the shower. He grabs her hand and he rapes her, what do you call, the maid” (Ralphie is talking about the TV news story he saw last night on television). “When he’s ready to go back to Paris his wife comes to New York to try to help him. His bail was a million dollars. He was a sex-crazed guy even though he was a diplomat. He’d done it more than once. Unbelievable. He thought she’d be afraid (the maid) to open her mouth, but he picked the wrong one this time.”

Frankie takes the conversation back to the topic of Biff Halloran, “Concrete King is a good name for a book,” Frankie said, “with the names changed.” Frankie knew I had interviewed Ralphie for my memoir to get down on record a few Sinatra memories and Frankie asked me to write Biff’s story down from his diaries. Frankie also asked me to help him outfit and launch his new yacht out of Kingston and I did. Frankie was always promising me jobs but really only wanted to “break me down” for sex, he later said. (It was impossible to break me. I’m in love with Sam, and Sam is my consummated betrothed, which is the same as being wed to the noble-hearted).

“Concrete King” made me think of my godmother Lady Jeanne Campbell’s grandfather, Lord Beaverbrook. Beaverbrook was in Winston Churchill’s War Cabinet. A Canadian, Beaverbrook had first made money in concrete. Before Beaverbrook became a statesman, he sold concrete. Then he bought several British newspapers.

Frankie and Ralphie kept talking over coffee and pie: “Women today are loose, soooo loose,” Frankie said.

“I can tell you why girls want to marry,” I offered and Frankie tilted back his head to regard me, his interest riveted, “We can’t shower our beloved with love until we are wed,” I continued.

“Not now, maybe in the 1950’s girls were like that, but not anymore. There isn’t anybody like you.” Frankie pointed his finger at me and narrowed his gaze, “And you are a thousand percent right!”

I thought of the Motown song “Chapel of Love,” written by Phil Spector and sung by the Dixie Cups.

Frankie said I possess the idealistic outlook of a twelve-year-old, “That’s what I say to people about you.” He shot me a sheepish glance, as if I might be mad. Frankie lived with a former inmate of Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Mansion.

Frankie said I could live in the Bahamas or live anywhere I choose, lead a millionaire’s life with him.

Many men have said the same thing. My answer is ever, “No, thank you.”

“Love is about personality and caring,” I explained to Ralphie and Frankie.

“I know,” Frankie wistfully replied.

“Laughter, fun talks, romance, and mutual appreciation are why I would never replace my sweetheart Sam. I wake up every morning, forgetting all the bad things and only remembering the good.”

“What’s that you call him?” Frankie asked. “You call him something.”

“Betrothed?” my face joyful. “It means to place all your trust in someone.”

“That’s a nice word,” responded Frankie. “I don’t want to break your chops, but let me ask you something. Your body doesn’t ever tell you something? Men and women are supposed to have sex. You are a woman,” began Frankie, “The mere fact of your innocence is attractive!”

“Sam once told me, ‘It’s you or nobody,’ and I feel the same. Sam is the only boy I will ever accept as my lover. And anyway, my betrothal is permanent.”

Frankie’s remarks reminded me of someone, a New York publishing friend named Larry who I call “Mouse.”

Why?” Mouse once asked me about Sam, “You loved this man totally; you have remained pure to this man; you have only given your body to this man.”