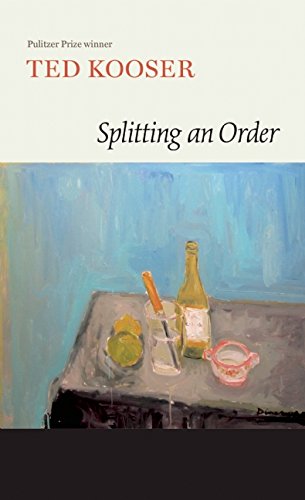

Splitting An Order by Ted Kooser / Copper Canyon Press / 2014 / 84 pages / 978-1556594694

Overview

The light of Ted Kooser is the everyday. To most of us these moments disappear, without recognition, without change, without endurance. Whether caught in a stare with an opossum, the arm swing of a rollerblader, or the gentle observation of an elder’s sweet kiss, Kooser’s words take us back to these moments and teach us a lesson: to never, never stop paying attention.

The light of Ted Kooser is the everyday. To most of us these moments disappear, without recognition, without change, without endurance. Whether caught in a stare with an opossum, the arm swing of a rollerblader, or the gentle observation of an elder’s sweet kiss, Kooser’s words take us back to these moments and teach us a lesson: to never, never stop paying attention.

A Presidential Professor in Poetry at the University of Nebraska, Kooser held the high distinction of Poet Laureate from 2004-2006, and he also won the Pulitzer Prize in 2005 for his revered work, Delights and Shadows. So where is Kooser in the world of poetry? He is an honored guest, revered.

Kooser’s collection of poetry, although subtly Nebraska, bends far beyond the state lines. In his words we are awakened, requested to uncover our loneliness and our fear, our trust and our love, and to stand up to them, boldly. It is with Kooser’s introspection that we are brought into his mental faculties, but with the evocative scenes he paints readers are invited to learn, to transform, to inspire.

Motif

Stripping moments to their bare bones, Kooser’s themes have a unique way of addressing time, almost as though she is character herself, blowing gently the moment of discovery where the past becomes the present; alternatively, the moment when the present crouches towards the future, such as in “The Woman Whose Husband was Dying”: “I saw the distance / before her slowly filling, as if from hidden springs,/ and she stepped outside, and placed one foot /and then the other on the future, and it held her up.”(25)

Even though many of the poet’s words deal with passing on, there is a reverence for life here that is quietly unmatched. I enjoyed the poems dedicated to one person helping another, “Two Men on an Errand” and “In a Gift Shop” in which two women select a card from a squeaky old rack:

And the rack turned round

As if it were the world itself (though with

A plaintive squeak), with the colorful days

Passing first into the light and then out

And with hundreds of thousands of women

like these, each helping another

do something for someone not there.

—17-18

And I loved the poems of change, the motion in them that seemed to thrill my beating heart, such as in “Changing Drivers”, “Swinging from Parents” and “A Morning in Early Spring”. Even the smallest movements here symbolize larger, bursts of life and their continuance to exist amongst the quiet and sustained, a rabbit bouncing in the yard, the drivers squinting in the sun, the parents swinging that child into forever.

Kooser’s poems are dripping in light: sunlight in “Gabardine” (24) , “Settled on the path like starlight” in “The Rollerblade” (16), “a long list of shadows” in “Snapshot” (20), “welcoming light” in “While We Were Passing” (22-23), “needing the light all around you” in “Bad News” (11), and “grown brighter with time” in “Estate Sale” (29-36), and many more to name.

In Kooser’s poems, light reflects everything: life, recognition, time, exuberance, and awareness. It is in between his broken shadows and his open skies that the reader is first invited to explore the valley of the spectrum, how we are not always who we think we are, we know not who we will become. In what light do we see the truth, in what truth do we see the light?

Craft

Kooser’s craft offers itself in several poetic forms, including a surprise personal essay in Section IV. With over twenty books of poetry published since 1969, I’m sure he has had his hand at them all. While Kooser begins in the concrete, he threads invisible strings throughout his words to lift the poem delicately into three dimensions. Suddenly the poem becomes transcendent, interacting with the reader in a new and interesting way, begging the reader for his or her own experiences, memories, and ideas.

In Kooser’s 2007 publication The Poetry Home Repair: Practical Advice for Beginning Poets (University of Nebraska, 2007), Kooser delivers this message: “Poetry is communication, and every word I’ve written here subscribes to that belief. Poetry’s purpose is to reach other people and to touch their hearts.”

In touching people’s hearts, Kooser uses everything from the pastoral tradition in “Potatoes”, “Jonathan in Summer” and “Deep Winter”, to the use of the stanza in “Estate Sale” and “While We Were Passing”, crafted more like list poems of extended descriptions. He also ventures successfully to fulfill poetry’s newest darling, the prose poem, in “An Incident” and “Splitting An Order”.

Retrospect

In Kooser’s poetry, I hear my father’s voice, and the wisdom of the Ted Kooser who this year will turn 75. Only in my middle age do I begin to notice the vitality of youth and the frailness of the elderly, which Kooser captures both delicately and intimately. Kooser writes about his own father, in “Those Summer Evenings,” and “Closing the Windows”, and I quell the rising lump in my throat in “Sleep Apnea”, knowing the wakeful silence of what Kooser calls “the guttering candle of my father’s breath” (62), with a father who suffers from a similar condition.

In Splitting An Order there is a lifetime of beginnings and endings and a courageous reflection of the meaning we build in between living moments. Kooser goes deeply into the past and bravely into the future, past death, connecting with the spirits, the ones he loved and lost, his old dog Alice, for example, or in the following quotation from “Hands in the Wind”:

Today I drove through a cloud of leaves,

pale oak leaves the color of hands

blown over the street, straight toward me

out of the empty parking lot

of the abandoned Kmart…

… It felt

as if all of the people I’ve loved

were suddenly swirling about me,

wanting to touch me, wishing me well.

—68

He has this beautiful way of crafting meaning in our lives, building a lifetime from the hammers and nails on our porches, the moths on our rocking chairs, the old brass door hinges into the boats of the clouds. This is our life, be ready to live it. We should all learn this from him. My inner voice says wants to say, ‘Thanks Dad,’ but instead to Ted Kooser, who quieted me down like a bouncing toddler, who I painted barns with, spent a cold winter, and reveled in the mysteries of life.

In first light I bend to one knee.

I fill the old bowl of my hands

with wet leaves, and lift them

to my face , a rich broth of brownsand yellows, and breathe the vapor,

spiced with oils and, I suspect,

just a pinch of cumin. This is my life,

none other like this.

—”A Morning in Early Spring”, 56-59

Leave a Reply