Last year, entirely by accident, I stumbled upon a censorship scandal that had been buried for the past fifty years.

The discovery happened at Saint Peter’s University, a small Jesuit school in Jersey City, New Jersey. It was an ordinary day at my work-study job in the library —a job which mostly consisted of scanning old documents, and on particularly exciting days, sifting through dusty boxes from the library archives. It was in one of these boxes that I uncovered a faded, typewritten letter. Upon further inspection, I found that the letter had been penned in defense of free speech — and that it had been authored by none other than the world-renowned poet, Allen Ginsberg.

Like most people, when I thought of Allen Ginsberg’s battle against censorship, I thought of “Howl,” the revolutionary poem that found itself at the center of a widely publicized obscenity trial in 1957. But as I pieced together the contents of the letter, I discovered that almost a decade later, Ginsberg had fought an entirely different crusade against censorship — one that was virtually forgotten to history until now.

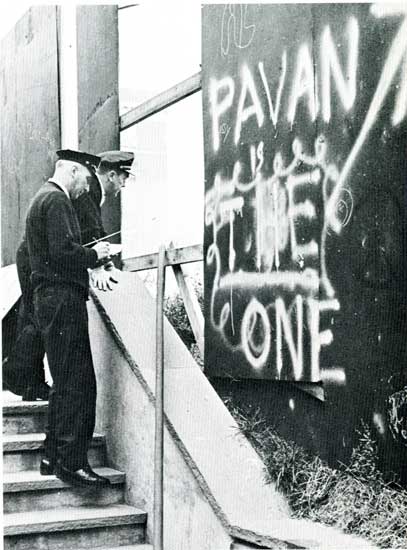

Our story begins in October of 1969, when the staff of Saint Peter’s relatively obscure literary magazine, The Pavan, did the unthinkable: they published a student’s poem comparing the Virgin Mary to a whore. The poem, written by George Thorry and entitled “A Fool’s Diary,” referred to Mary of Nazareth as a woman who was “rather lewd” with “coptic crabs.” If that wasn’t enough to offend the religious sensibilities of the university administration, what followed would certainly do the trick: a few pages later was an untitled piece by Bill McNeal graphically depicting a back-alley abortion.

According to Thorry, his poem was simply “an exorcism of an image.” Of course, the school’s President believed otherwise. Father Yantinelli was a bespectacled Jesuit priest whose local influence was so profound that he had just been named Jersey City’s “Man of the Year” — and the last thing he needed was for the college to be associated with a publication whose content was so blatantly objectionable and sacrilegious. So when the latest issue of The Pavan was brought to Father Yantinelli’s attention, he knew there was only one thing to do: the magazine’s funds had to be frozen indefinitely. To justify cutting The Pavan’s budget to the magazine’s editor, Bill Scheller, Father Yantinelli cited the two poems, which he claimed were both “blasphemous and scatological.”

The editors of The Pavan immediately issued a statement: “This is an attempt by the administration to silence our magazine with a financial death blow,” they declared. “The Pavan will continue to publish, with or without their money.” Meanwhile, when the student body heard The Pavan had been censored, the magazine’s popularity soared like never before. “Pavans were going faster than free Playboys,” wrote one student, James Dixon, in a 1970 editorial. “Students who had never heard of the The Pavan suddenly developed great literary interest.”

Word of the controversy quickly made its way to wealthy alumni, who, in Dixon’s words, “read the issue with literary credentials called M-O-N-E-Y.” Many of the alumni viewed the latest issue of the The Pavan as a major threat to Father Yantinelli’s promise that, despite the fact that Saint Peter’s had recently gone co-ed, renounced the dress code, and no longer considered ROTC mandatory, “he would not allow Saint Peter’s to become another Berkeley.” This was a promise the university took seriously — so seriously that their Dean of Students was an informant for the Newark chapter of the FBI, dutifully reporting “all leftist activities” on campus.

Saint Peter’s was humble, working-class, Catholic, and, for the most part, anonymous. It was the kind of school where, according to one student, “most kids wished to stay out of the fray, get their degree, and move on.” But still, there had been protests. The year before, Nixon had visited Saint Peter’s on his presidential campaign, only to be relentlessly heckled by the students. (“I’ve been heckled by professionals before,” Nixon jeered back. “It’s nice to be heckled by amateurs.”) And, only a few months before The Pavan controversy, students had gone on strike and occupied the Dean’s office after two popular left-wing professors were refused tenure — a feat which, though unsuccessful, landed them on the front page of several local papers.

The increasing levels of political activity on campus may have been why Francis X. Bierne, a Jersey City tax collector who had graduated from Saint Peter’s in 1953, was particularly enraged by the poems. In a Jersey Journal op-ed, he wrote, “Hanging [Thorry, McNeil, and Scheller] from the highest tree on the hallowed campus ground would be a mild punishment. Perhaps, rolling them out on Kennedy Boulevard so that the buses and vehicles could press them out in pieces smaller than their character might be more suitable to the crime they committed on the saintly name of Saint Peter’s.”

(In response, Scheller’s mother wrote an op-ed of her own: “Mr. Bierne has never met my son William,” she wrote. “He is not a plastic saint who has been cast in a mold. He is an individual who has been taught to think for himself…He takes his job as Editor seriously, and has worked hard at it.”)

Alumni weren’t the only ones offended by Thorry and McNeil’s poems. “We received a firestorm of letters, some of which were really nasty,” remembered Scheller. Shortly after the magazine’s budget was cut, someone slipped a note under the door of the The Pavan headquarters, signed only “A Concerned Student.” “I think Father Yantinelli was totally right,” the note read. “You should have your balls cut off, you hippie fucks.” The Pavan staff wasted no time shooting back in a letter from the editors: “Seems we’re not the only scatologists around,” they wrote.

“We were used to fighting it out over the [Vietnam] war,” Scheller recalled. “So when all of a sudden this Pavan came out, pretty much the same split occurred.”

George Thorry, author of “A Fool’s Diary,” was spending a semester abroad in Ireland while the controversy unfolded. He kept updated on the drama through letters from his girlfriend, who attended Saint Peter’s.“I felt kind of helpless, being thousands of miles away while all this was going down,” he admitted. “I thought I was gonna get kicked out of school.”

Not all of the attention the scandal received was negative, however. Eventually, the story made its way to the radio and the New York Times, where the publicity it received brought in letters of support from alumni, doctors, lawyers, and writers. Many of the letters contained donations to subsidize the cost of printing an underground issue of The Pavan.

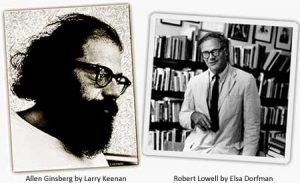

But perhaps The Pavan‘s most passionate advocate was Ginsberg, who was no stranger to censorship himself. Ginsberg’s relationship with The Pavan staff had begun a few months before, when he had appeared at Saint Peter’s College for a poetry reading, albeit under rather unusual circumstances. Shortly before the reading, Ginsberg had survived an auto accident which had left him temporarily paralyzed. Despite his condition, Ginsberg agreed to rise from his sickbed and speak at Saint Peter’s if — and only if — “he would not be required to get around of his own volition.”

Eager to ensure that Ginsberg would still appear on campus, Scheller secured an ad in the student newspaper, The Pauw Wow, where he notified the student body that interviews would soon be held to determine who would have the great honor of shouldering Ginsberg during his sojourn at Saint Peter’s. Apparently, Scheller found his volunteers — and Ginsberg spoke at the college in April of 1969, slurring due to his facial palsy but, according to the Newark Sunday News, “reading his poetry in a dramatic, well-modulated voice” just the same. By his side and ready to step in should Allen fall ill was his father, Louis Ginsberg, also a poet. The talk was advertised as “two Ginsbergs for the price of one.”

As the Ginsbergs spoke, students burned incense and sat cross-legged on a broken tree branch someone had dragged in from outside. The room was transfixed by Allen Ginsberg’s anti-war elegy, “Witchita Vortex Sutra,” and his tale of Amiri Baraka (then known as Le Roi Jones) a black poet who had been unjustly arrested during the Newark riots two years before. “It wasn’t just a poetry reading,” one alumnus, Richard Mara, recalled. “We were trying to set up a new social and political order…it was exhilarating.” Afterwards, students gifted Allen Ginsberg with a red armband in solidarity with the 1969 student strike at Harvard — much to the dismay of Louis, who was far more straight-laced and traditional. (“Allen likes the hippies,” Louis said to a reporter after the reading.“I say you can’t be an adolescent all your life. How long can you be without a job, sing songs, and stand on a street corner wearing beads?”)

Because of his warm reception at the college, Ginsberg rushed to the defense of Scheller, McNeal, and Thorry. “There are no pure motives and never have been in the censorship of poetry,” he wrote in a letter to the Saint Peter’s Board of Trustees, who had unanimously voted to sanction Fr. Yantinelli’s suppression of The Pavan. “This country was not founded for a bunch of prurient bureaucrats to rush around being thought police over Citizen’s poetry.”

Ginsberg’s letter did more than just defend the literary merit of Thorry and McNeal’s poems– it also referred to the cover of the controversial issue, which, in Scheller’s words, “had only added fuel to the fire.” On the cover of the 1969 The Pavan, depicted in a grainy black and white photograph, was an apartment door with a broken lock. The caption was short, sweet and incendiary: “courtesy of the Jersey City narcotics squad.”

“At the time, I shared an apartment with several of my friends,” Scheller explained. “I was on my way to print The Pavan when I got in a car accident.” Scheller headed back to his apartment, only to find that the narcotics squad had broken in to arrest an acquaintance of his who had been dealing marijuana. On impulse, Scheller snapped a picture of the busted lock — “and suddenly,” he said, “we had an idea for a different cover.”

For this reason, Ginsberg’s letter condemned Saint Peter’s College not only for the censorship of the poems, but for “forbidding students to reprint photographs of obnoxious un-American behavior by police,” especially after police agencies in New York and New Jersey had been caught pushing heroin and cooperating with the mafia. “The mafia wants these students’ door busted down,” Ginsberg wrote. To prevent the photograph from being distributed was nothing more than “built-in authoritarian cowardice of the ‘Good German’ tradition.”

He went on, “Be careful whose door you bust, whose poem you censor, and whose photography you declare too ‘private’ for the public eye. This generation of students and poets have found out many embarrassing secret facts about the way of life we have lived which has led to a planetary ecological crisis, secrets of police state, overpopulation, thought control, destruction of human nature. If we cannot make these images public neither the nation nor the world will survive.”

Ginsberg wasn’t the only famous writer to come to the defense of The Pavan. Sol Yorick, a novelist known for his book The Warriors, also penned a letter to Saint Peter’s Board of Trustees. In his letter, he spoke not just about free speech but on the morality of censoring a poem that exposed the horrors of back-alley abortions. “I read The Pavan out loud, from cover to cover, to my five year old daughter,” he continued. “She forgot to watch TV that night, so I consider The Pavan to be socially redeeming.”

Ultimately, The Pavan was able to print an underground issue through the help of a printer who agreed to print the issue at no cost. (Depending on who you ask, this was either “in the name of free speech” or “because he wanted to get the contract to do the printing once The Pavan got its budget back.”)

The issue contained Ginsberg’s poem, “Swirls of Black Dust on Avenue D,” which he had submitted for publication in solidarity with the students. It also started with a snarky declaration from the editors: “The views and expressions printed in The Pavan are not necessarily those of the Administration, the Pope, or the class of 1908,” it read. “And we are not consciously trying to offend the sensibilities of any member of the college community, although you are free to lick your wounds if you feel afflicted.”

Much to the chagrin of the administration, George Thorry, author of “A Fool’s Diary,” returned home from Ireland to find himself unanimously elected next year’s editor of The Pavan. Shortly after, the Student Senate, somehow oblivious to the controversy despite the fact that it had made national headlines, innocently passed The Pavan’s budget request for the next year. In hopes that they could put the issue to rest once and for all, the administration decided not to rescind the budget that had been passed.

The Pavan has not been censored since — but Saint Peter’s history of censorship didn’t end in 1969. In 2016, Saint Peter’s University made headlines for cutting off the budget of the student newspaper, the Pauw Wow, after the staff published a Valentine’s Day issue focusing on sex.

Unlike students at public universities, students at private institutions are not protected by the First Amendment. According to Gabriella Robles, an alumna who was on the staff of Pauw Wow when its budget was cut in 2016, this makes students at Saint Peter’s much more susceptible to censorship.

“Student newspapers are the only form of organized media whose sole purpose is to report on a specific campus community,” Robles said. “If student newspapers aren’t looking deeply at administrators, faculty, the student body and the actions happening around them, no one else will.”

Today, The Pavan’s former editor, Bill Scheller, lives in Vermont and is the author of over 30 books. He wasn’t surprised to learn that The Pavan scandal had been forgotten after nearly fifty years — but he believes that the controversy is more relevant than ever. “1969 was a flashing point in our history,” he said. “That was the last time that things were as sharply divided as they are right now.”

George Bowering says

I found this an interesting and welcome article. I only wonder how a typewritten letter can be said to be “penned.”

Alison Winfield Burns says

Excellent, truthful article and timely, relevant commentary by Allen Ginsberg (as always can be expected).

Rachel Wifall says

This year’s Pavan will be commemorating this incident, 50 years ago, and also addressing today’s social ills. Thanks for all this research, Loretta. Great job!

Bruce Hodder says

Fascinating essay. Thank you for sharing it. I’ve been a fan of Ginsberg’s poetry for years and I had no idea about this – although it was characteristic of him to get involved.