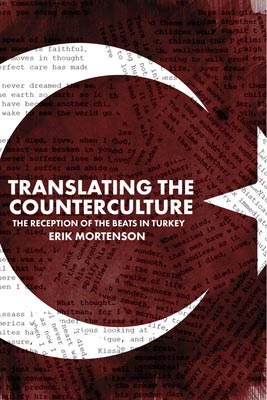

TRANSLATING THE COUNTERCULTURE The Reception of the Beats in Turkey by Erik Mortenson / Southern Illinois University Press / 978-0809336548 / 2018

The premise is a fascinating one. Erik Mortenson actually was IN Turkey during its attempted coup in 2016 and had to leave with his family. He taught at the Koç University in Istanbul, so this is no thesis conducted from afar. Mortenson became direct witness to an increasing infiltration and interest in the Beats.

So, we immediately have the specific factual impact of a literary movement from the United States that the Whitney Museum’s groundbreaking mid-90s show places between 1950 to 1965. This in itself shuts down an argument of the current relevance of the Beats.

The term “Underground” is the dominant one used in Turkey for this and related literature. Of significance, Beat is by no means exclusively of male interest even with its predominantly male view. The Beats became internationally influential especially in the so-called Hippie movement, but not all Beats entered that movement and all of them survived it in relevancy. Still, the Punk culture that followed in the late 1970s (which Allen Ginsberg embraced and William Burroughs was exalted by) has absolutely nothing to do with tie-dye or the Grateful Dead quite intentionally. Of course, the even-later Burning Man phenomenon managed to meld Beat/Hippie/Punk into not-so-strange bedfellows, but that opens its own discourse of essay proportions. All of this collides in modern Turkey as “Underground.” Still, as Mortenson points out, the emphasis is much more “beaten down” than “beatific.”

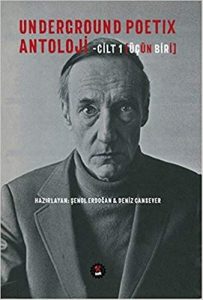

He also makes the interesting point that there is a frat boy mentality to the earlier publications – showing the dominant male instigation and its objectification of women that is obviously part of the interest and baggage of its source material. At the same time, Turkish Beat anthologist Şenol Erdoğan makes the point that lumping in hippie writers with the Beats is sloppy and the result of monetary interest. It is of course an unresolved argument when we can place Neal Cassady as the driver of the Merry Pranksters’ acid bus, Further.

Underground Poetix serves as a sort of open mike for Post-Beat poets who once more echo the tendency to use a do-it-yourself kit that Beat literature provides, similar to the Punk ethos that allowed bands to be formed without conventional musical or vocal ability. So, yes, some of the poetry is not so good, to say the least, but there are also some really interesting moments as well.

On the Road gets its own chapter, so Mortenson can fully examine that running wild has quite a different flavor depending on how dangerous the terrain. Likewise, it is possible that On the Road may only make sense when there is a middle class to walk away from. Issues of race and gender also come up with Mortenson’s students, but the data he’s collected shows that Charles Bukowski surpasses any other “Underground” writer in popularity, once more demonstrating the beaten-down focus rather than the beatific. Of course, most of my readers are already aware of the uncomfortably coterminous fit Bukowski has with Beat writers — perhaps better understood when brought back to the influence and permission of earlier writers like Henry Miller. Still, what makes On the Road survive internationally all these decades is the quest for authenticity and essential meaning — the impulse to be free of arbitrary rules and conceptual shackles that the internet itself has helped reveal in its own global freedom — and attempted censorship.

Next, William Burroughs, who is the least popular of the Beats in Turkey. The romanticism of the criminal outcast (as in being a “junkie”) is also not an easy view for a country where community very much survives. In particular, Mortenson covers the censorship trial of The Soft Machine, which occurred in Turkey as late as 2012! In passing, Mortenson mentions that there are several versions of the novel Burroughs revised himself, which I didn’t know. Burroughs scholar Jeffrey Ball explained it to me: “There are 3 different Soft Machines: Olympia (1961); Grove (1966); and Calder (1968)…all different from each other.”

Regardless, one can assume that whatever version is translated, it is no less explicit in detail concerning Burroughs’ fascination with ejaculation by hanging and a variety of sci-fi homosex and necrotic collisions. Various intellectuals and university types weighed in at the trial, and I almost laughed out loud at some of their efforts at defense. Summing up, they thought the book shouldn’t be censored, even if they were often personally repulsed and found the cut-up annoyingly fragmented and incoherent. Even the little bit that was quoted by Mortenson reminded me how much I enjoyed the book and how much easier I found it than reading James Joyce or Ezra Pound (both whom I love but required a lot more work).

In terms of translation itself, Mortenson finally turns to Allen Ginsberg and this time breaks down how translation works. It is quite a revelation, even if the results should be expected. Imagining being unable to read Ginsberg in English immediately suggests the problem of attempting to read outside of any author’s native tongue. The “madman bum and angel beat in Time, unknown” of “Howl” is rendered as both “madman, bum, and time’s angelically beaten ones, beat, unknown” and “mad bum in Time, and sanctified angel, unknown.” The term “Beat” itself gets different words as well – one the expected “downtrodden”, the other “sanctified.”

The second’s accessibility opens into Turkey’s own tradition of Sufi mysticism, though Mortenson glosses that “the Beats seldom (if ever) referenced” them. Ah, but Ginsberg did! In 1967’s “Wichita Vortex Sutra”: “…chanting La illaha el (lill) Allah hu [There is no God than God Only] revolving my head to my heart like my mother” which he undoubtedly got from Sufi Sam, active as mystic teacher in San Francisco 1967 and mentioned by name in Ginsberg’s “Jahweh and Allah Battle” 1974. Ginsberg actually made it to Turkey in the Summer of 1990, and was just as interested in Turkey’s poetry scene as they were in him – though it sounds like neither felt there was enough time to be satisfied.

Turkish poet küçük iskender unfortunately did not meet Allen that visit. He spells his name in lowercase like e.e. cummings or ruth weiss and is the inheritor of the bad boy poet tradition. His own work is definitely Post-Beat, long-lined in breath and quite good: “I want sex-shops, a communist party, a Muslim democratic party…I wanna see Nobels, Oscars, LSD, freedom and cock monuments in this land…” There is no doubt that the torch is passed. That’s deeply moving and inspiring.

Talking to his fellow academics first and foremost, Mortenson still manages to deliver some great thought-provoking information. He mostly leaves the denser academic-speak for the Notes at the end. Alas, the book is an expensive one, so score it through your library if you can.

Leave a Reply