During the summer of 1956, Jack Kerouac stayed on two occasions at the Hotel Stevens in downtown Seattle. His first stay at the venerable old “skid row” hotel was in the latter part of June of that year, his second stay there some eighty days later in early September. Between these two brief stopovers, pivotal psychological and spiritual events took place in Kerouac’s life, so that his separate sojourns at the Hotel Stevens stand positioned – like bookends – on either side of what was for Kerouac a crisis, a reversal, and a reorientation.

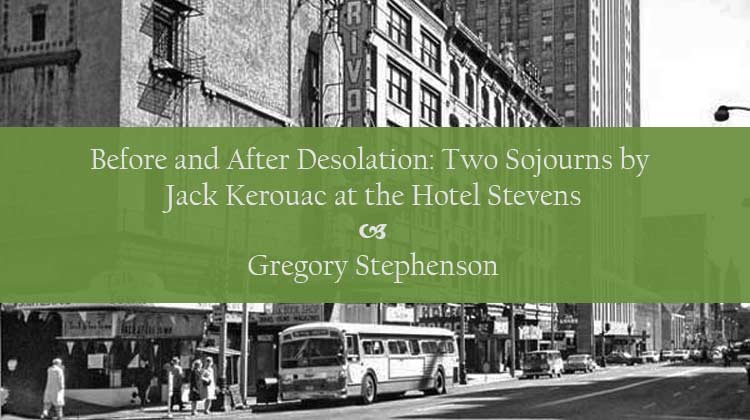

In a letter to his friend Gary Snyder, Kerouac recounts how after a long journey north, reaching Seattle, he “got skid row room 15 foot ceiling and read VajChePraPar.”2 (Kerouac is referring here to the Vajracchedika Prajnaparmita Sutra or “The Diamond Scripture,” an ancient Buddhist text emphasizing the practices of non-abiding and non-attachment in attaining to a perfected way of seeing the nature of reality.) In Desolation Angels (1965), writing as the narrator, Jack Duluoz, Kerouac describes the Hotel Stevens in the following manner: “Hotel Stevens is an old clean hotel, you look in the big windows and see a clean tile floor and spittoons and old leather chairs and a clock talking and a silver-rimmed clerk in the cage – a dollar seventy-five for one night, steep for Skid Row, but no bed bugs, that’s important.”3

Staying at the Hotel Stevens for the first time, en route to his job with the Forest Service as a fire lookout atop Desolation Peak, then, Kerouac stayed in his room, piously studying sacred scriptures in anticipation of some form of illumination in the solitude of the mountain summit. This aspiration is expressed in a personal letter Kerouac wrote to his friend, Lucien Carr, on February 24, 1956, wherein he writes (jocularly but sincerely) of his hope that the seclusion and silence of the remote mountain peak will serve to catalyze in his mind and spirit a transformative, redemptive experience: “If I don’t get a vision on Desolation Peak my name ain’t Blake.”4 Returning to the Hotel Stevens eleven weeks after his initial stay there, having at this time just finished his assigned tour of duty on the mountaintop, Kerouac no longer devotes himself to the study of hallowed scriptures alone in his room but, instead, plunges eagerly into the whirling life of the world, hurling himself into a gyre of appetites and desires.

Midway between these two chronological co-ordinates, bracketed by Kerouac’s separate sojourns at the Hotel Stevens, there lies a third point in time at which the author undergoes a kind of reverse conversion experience. In Desolation Angels, the author’s alter ego, Jack Duluoz, recounts the slow erosion of his spiritual aspirations on the summit of Desolation Peak: “I’d thought, in June, hitch hiking up there to the Skagit Valley I northwest Washington for my fire lookout job `When I get to the top of Desolation Peak … I will come face to face with God or Tathagata and find out once and for all what is the meaning of all this existence and suffering and going to and fro in vain´ but instead I’d come face to face with myself, no liquor, no drugs, no chance of faking it but face to face with ole Hateful Duluoz Me and many’s the time I thought I’d die, suspire of boredom, or jump off the mountain.”5 Instead of the clarity to which he hoped to attain, the author experiences confusion, as expressed in the 6th Chorus of his poem “Desolation Blues:” “I just don’t / Dont / Understand / I don’t — / I want to know / …/ I don’t understand.”6 In the 7th chorus of “Desolation Blues,” Kerouac admits that he now wants to forsake his solitary, ascetic existence on Desolation Peak, forsake his earnest, determined quest for illumination and salvation, and, instead, return to the world below with its cities and streets, return to wine, to delectable foods and sweets, to drugs and women and all the exciting, satisfying sensual indulgences available in the material world. As John Suiter observes in Poets on the Peaks: “Without the stimulation of a visceral ‘Desolation satori,’ Jack’s longing for the realm of the senses grew ever more acute.”7 Or, as Philip Connors, a sympathetic fellow fire-lookout who once hand-copied Kerouac’s Desolation Peak diary, comments: “For Kerouac the path of Buddhism proved too difficult, too alien to his temperament.”8

In consequence of his disappointment at having failed to receive a revelation of some kind on Desolation Peak, the author turns inwardly and then physically from the mountaintop (his idealized former objective) to “the valleys” and “the flatlands” below (see 5th Chorus of “Desolation Blues”). In more than one sense, then, at length he descends the mountain and seeks solace in what the King James Bible calls “the cities of the plain.”9 The Kerouac narrator may now be through with the mountain, but the mountain – as it were – is not yet through with him. This first becomes evident when Duluoz / Kerouac reaches Seattle and the temporary sanctuary of the Hotel Stevens.

In the mid 1950s, at the time of Kerouac’s two stays at the Hotel Stevens, the old establishment – built on the corner of First Avenue and Marion in the 1890s – was long past its glory days and had become, as the author describes it, a somewhat shabby “skid row” hotel. The Stevens was exactly the kind of hotel that Kerouac cherished, not only because it was cheap and clean, but also because of its connection to the wild pioneer past of the northwest. A lingering link to the frontier past can be seen in the presence of spittoons in the lobby of the Hotel Stevens, as noted in Kerouac’s description of the hotel (above) in Desolation Angels. In the 1950s remnants of the late frontier could still be found across the western states in the form of old buildings and other artifacts. (See, for example, the decrepit hotels and broken-down barbershops of Neal Cassady’s childhood in and around Larimer Street in Denver as described in The First Third, and Kerouac’s fascination with the weatherbeaten shacks and barns and gloomy poolhalls of the old west, as recorded in his Book of Sketches.)10 And, as if in anticipation of the pilgrim’s disheartened, life-hungry return from his mountain hermitage, in the street below Kerouac’s room at the Hotel Stevens are to be found all the excitements and enticements of a big city night: the bright stores and lively crowds, the roaring bars, the wafting food smells of restaurants, and an oldtime burlesque theatre.

In the mid 1950s, at the time of Kerouac’s two stays at the Hotel Stevens, the old establishment – built on the corner of First Avenue and Marion in the 1890s – was long past its glory days and had become, as the author describes it, a somewhat shabby “skid row” hotel. The Stevens was exactly the kind of hotel that Kerouac cherished, not only because it was cheap and clean, but also because of its connection to the wild pioneer past of the northwest. A lingering link to the frontier past can be seen in the presence of spittoons in the lobby of the Hotel Stevens, as noted in Kerouac’s description of the hotel (above) in Desolation Angels. In the 1950s remnants of the late frontier could still be found across the western states in the form of old buildings and other artifacts. (See, for example, the decrepit hotels and broken-down barbershops of Neal Cassady’s childhood in and around Larimer Street in Denver as described in The First Third, and Kerouac’s fascination with the weatherbeaten shacks and barns and gloomy poolhalls of the old west, as recorded in his Book of Sketches.)10 And, as if in anticipation of the pilgrim’s disheartened, life-hungry return from his mountain hermitage, in the street below Kerouac’s room at the Hotel Stevens are to be found all the excitements and enticements of a big city night: the bright stores and lively crowds, the roaring bars, the wafting food smells of restaurants, and an oldtime burlesque theatre.

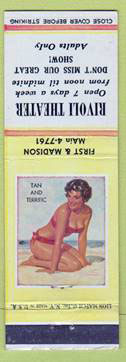

All of these attractions are eagerly sampled and savoured by Kerouac during the course of his post-Desolation sojourn at the Stevens. Afoot and alert in the streets of the city, Kerouac immerses his senses in all the things of which they have been so long deprived on Desolation Peak. His unaccustomed eyes marvel to see the myriad and variety of lives in the world: “humanity hep and weird wandering on the evening sidewalk amazing me outa my eyeballs.”11 He humbly admits that for all his days of praying and pacing alone atop the mountain, the unspoken prayers of those he sees in the streets are as valid as his meditations and invocations, and he perceives that in each human heart there is latent love. He enjoys a cold beer in a crowded downtown bar, watching a prize fight on television with the other customers, feeling a kinship with them and with others across America. Later, alone in his room at the Hotel Stevens, Kerouac drinks port wine, while reading, not the Vajracchedika Prajnaparmita Sutra, but Time magazine and The Sporting News, reintegrating himself in the affairs and events of the world. Returning then to the evening streets, Kerouac surreptitiously swigs his fortified wine from a plastic canteen he’s filled as he relishes the pageant of the phenomenal world with all its diverse sights and sounds, recognizing how intensely he loves the world. High on wine, he attends a burlesque show, grooving to the jazz accompaniment, lusting for the dancers, all while becoming increasingly intoxicated on his secret canteen of wine. His excursion into the domain of the senses is crowned with a delicious Chinese dinner followed by a hot tub bath and long soothing sleep in a soft bed at the Hotel Stevens.

The critic and scholar, Jim Jones, has identified the burlesque venue at which Kerouac attended striptease shows in September 1956 as The Rivoli Theater, a conclusion in which author, Tim Appelo, concurs.12 The Rivoli was located on First Avenue only a few steps from the entrance to the Hotel Stevens and like the Stevens, was a remnant of an earlier era, having been built in 1913. Accomplished local organists such as Eddie Zollman and Wally Stevenson played the 2/5 Kimball pipe organ for strip shows at the Rivoli, and one or the other of these musicians may have been the organist so admired for his jazz skills by Kerouac in Desolation Angels. By the 1960s, the Rivoli had become a porn theatre. The building was demolished in 1970 (as was also the Hotel Stevens) and replaced by the Henry Jackson Federal Building, a 37 story skyscraper. The fate of the Hotel Stevens and the Rivoli Theater seems poignantly symbolic of the final eradication of the last traces of a certain rowdy, wide-open frontier spirit – a spirit celebrated in Kerouac’s writing – and its replacement by a bland, slick and soulless new era. But, that all is in a state of flux, all fleeting and fugitive, would have come to Kerouac as no surprise.

In the wake of his failed mountain vigil, Kerouac strives to reconcile his conflicting desires for spiritual attainment and for self-gratification, struggling to order his life in the world in a manner consistent with his ideals and beliefs. Preoccupied while on Desolation Peak with images of future sensuous enjoyment, Kerouac now finds that, having at last reached “the flatlands” for which he yearned and there indulged his appetites for sensation and intoxication, he is persistently haunted by thoughts and perceptions of a spiritual nature and even by a longing for his recent life of solitude atop Desolation Peak. On the sidewalks of Seattle, in the bar, alone in his room at the hotel, Kerouac cannot evade an awareness – engendered by his Buddhist beliefs – that all that he perceives exists ephemerally in “the unlimited void … in the mind of the universe,” and that ultimately nothing possesses reality or being apart from “mindmatter essence primordial.”13 Later that same evening, even during the most erotic moments of the burlesque performance, the author is uncomfortably conscious of a deeper level of reality underlying all things: “I see files of sorrowing humanity wailing by candlelight and Jesus on the Cross and Buddha sitting beneath the Bo Tree and Mohammed in a cave ….”14 Drunk, dizzy, lonely and bewildered by the world, Kerouac remembers wistfully the mountain hermitage he so recently left: “I better go back to my rock.”15

Kerouac’s evening of diversion and immersion in the pleasures of the senses culminates in an insight clearly related to his solitary studies and meditations on Desolation Peak. Leaving the burlesque theatre and standing on the sidewalk in the night air, returned abruptly from a realm of erotic illusion to gray reality, he sees two male performers and the organist from the burlesque house, scurrying up the street in an effort to get back to the theatre in time for the next performance. In an instant, the stage personae created by the entertainers and Kerouac’s fantasies concerning the musician (as smooth, seductive lover of one of the strippers) collapse, as he sees the three men as “ordinary … as troupers, vaudevillians, sad, sad – making a living in the dark sad earth.”16 This perception causes him to reflect that we are all mortals, transient, passing, and that all of us and all that we behold will one day vanish, even the heavens will disappear. The burlesque show may thus be seen as an implicit metaphor for the Buddhist concept of maya: just a show, an illusion of reality, a flimsy surface actuality, but ultimately insubstantial, unreal, uneternal.

In a similar fashion, Kerouac’s separate stays at the Hotel Stevens can be seen to reflect his inner division: his sincere pursuit of spiritual growth in opposition to the powerful attraction of the pleasures of the senses. This conflict – between the spirit and the flesh – is central not only to Kerouac’s life and writing but is, of course, a perennial theme in literature and, indeed, an abiding aspect of the human condition. The Desolation episode, flanked on either side by sojourns at the Hotel Stevens, is pivotal in The Duluoz Legend, as it also proved to be in the life of the author. Ahead for the author-narrator lay other rooms, further nights, days and distances, further ordeals and epiphanies. Having accommodated Kerouac with two night’s lodging – first as antechamber and then as terminus – the Hotel Stevens was for this lonesome traveler a critical way station on his journey through the world.

Notes

1 The Dharma Bums by Jack Kerouac, New York: 1958, p. 221.

2 “Jack’s Haiku Letter to Gary,” The New Black Bart Poetry Society, <https://thenewblackbartpoetrysociety.wordpress.com/>.

3 Desolation Angels by Jack Kerouac, New York: Coward-McCann, 1965, p. 105.

4 Letter from Jack Kerouac to Lucien Carr in Selected Letters 1940-1956, ed. by Ann Charters, New York: Viking, 1995, p. 564.

5 Desolation Angels, p. 4.

6 “Desolation Blues” in Book of Blues by Jack Kerouac, New York: Penguin, 1995, p. 122.

7 Poets on the Peaks by John Suiter, Washington, District of Columbia: 2002, p. 223.

8 Fire Season by Philip Connors, London: Pan Books, 2011, pp. 190-191.

9 Genesis 19:29, King James Version.

10 The First Third by Neal Cassady, San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1971. Book of Sketches by Jack Kerouac, London: Penguin Books, 2006.

11 Desolation Angels, pp, 101-102.

12 Kerouac in Seattle by Jim Jones, Salt Lake City: Elik Press, 2004, p. 20. “Beneath the Cloudmopped Skies” by Tim Appelo, City Arts Magazine, October 28, 2009, <https://www.cityartsmagazine.com>.

13 Desolation Angels, p. 103. See also “Seattle Burlesque” by Jack Kerouac in Evergreen Review, Vol. 1, No. 4, 1957, pp. 106-112.

14 Ibid. pp. 109-110.

15 Ibid. p. 110.

16 Ibid. pp. 110-111.

Leave a Reply