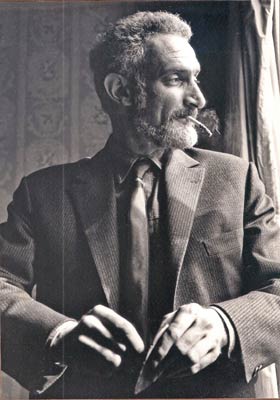

Photo by Frank Monaco, courtesy of Earl Rubington

Akbar del Piombo — illustrious subterranean luminary, mysterious, pseudonymous author of six darkly comic, wildly satirical collage novels. Akbar del Piombo — preposterous, portentous name, once widely believed to be a nom-de-plume of William S. Burroughs. Akbar del Piombo — the name itself a kind of collage, fittingly inconsonant for a virtuoso of the incongruous.

Concealed behind the Akbar del Piombo pen name were the mordant eye and fertile brain of Norman Rubington (1921-1991). Rubington was an acclaimed American artist — painter, sculptor, illustrator and filmmaker — who lived much of his adult life abroad, chiefly in Paris and Rome. Born in New Haven, Connecticut, he later studied at the Yale School of Fine Arts. During World War II, he served for three years in the U.S. Army, stationed in China. Moving to Paris in 1946, he supported himself there on the G.I. Bill and by writing pornographic novels for the Olympia Press. It was in this latter capacity that he assumed the exotic nom-de-plume of Akbar del Piombo, subsequently choosing to publish his collage novels under that same ill-famed, fabled name.

Rubington’s collage novels were clearly inspired by those of Max Ernst (1891-1976) whose original and important works in this genre include La Femme 100 Tetes (1929), Reve d’une petite fille qui voulait entrer au Carmel (1930) and Une Semaine de Bonté (1934). Carefully clipping images from 19th century and early 20th century steel-engravings, Ernst reassembled them in incongruous combinations creating fantastical, unsettling pictures that were then arranged in sequence and gathered together as a volume, forming a dream-like narrative. Ernst’s collage novels sometimes included brief texts or captions, related only obliquely to the situations depicted in the images.

Using source materials and methods similar to those used by Ernst to fashion his own collages, Rubington brought vital innovations to the collage novels he devised. These included the addition of extended prose texts recounting a series of linked incidents related (often ironically) to the collage illustrations, the use of word balloons in the collages, the arrangement of collages in multiple panel sequence, the technique of dislocating and recontextualizing unretouched original images (as I shall explain later) and the expression of more explicit, more topical satirical themes. Rubington’s collage novels can thus be seen as among the precursors to the modern graphic novel, and with their futuristic settings and alternate versions of reality, can also be seen as a species of speculative fiction.

The first of the Akbar del Piombo collage novels — and probably the best known of the six – is Fuzz Against Junk (1959). First published by the Olympia Press in Paris, the book was then marketed in the U.S. by the Citadel Press, later reprinted by New English Library and by Beach Books, and subsequently serialized in the pages of Rolling Stone magazine. Subtitled “The Saga of the Narcotics Brigade,” the novel recounts the exploits of Sir Edwin Fuzz, “foremost narcotics expert of the United Kingdom and sleuth par excellence,” who is summoned to New York city to aid in combating an unparalleled outbreak of criminality there, the consequence of an equally unprecedented epidemic of heroin addiction. The prime mover of the burgeoning rate of drug addiction and its attendant wave of violent crime is an elusive figure known as “The Man,” a criminal genius and a master of disguise. On the basis of the evidence presented to him by New York police, Sir Edwin shrewdly concludes that the true epicentre of the mayhem besetting the city of New York lies at the other end of the continent in San Francisco. Sir Edwin then leads a band of detectives to San Francisco where they disguise themselves as “beatniks,” infiltrate the drug milieu of that city, and ultimately succeed in capturing “The Man,” who, faced with imprisonment for his multitudinous misdeeds, chooses, instead, to commit suicide.

The first of the Akbar del Piombo collage novels — and probably the best known of the six – is Fuzz Against Junk (1959). First published by the Olympia Press in Paris, the book was then marketed in the U.S. by the Citadel Press, later reprinted by New English Library and by Beach Books, and subsequently serialized in the pages of Rolling Stone magazine. Subtitled “The Saga of the Narcotics Brigade,” the novel recounts the exploits of Sir Edwin Fuzz, “foremost narcotics expert of the United Kingdom and sleuth par excellence,” who is summoned to New York city to aid in combating an unparalleled outbreak of criminality there, the consequence of an equally unprecedented epidemic of heroin addiction. The prime mover of the burgeoning rate of drug addiction and its attendant wave of violent crime is an elusive figure known as “The Man,” a criminal genius and a master of disguise. On the basis of the evidence presented to him by New York police, Sir Edwin shrewdly concludes that the true epicentre of the mayhem besetting the city of New York lies at the other end of the continent in San Francisco. Sir Edwin then leads a band of detectives to San Francisco where they disguise themselves as “beatniks,” infiltrate the drug milieu of that city, and ultimately succeed in capturing “The Man,” who, faced with imprisonment for his multitudinous misdeeds, chooses, instead, to commit suicide.

Although certain of the illustrations in Fuzz Against Junk have been modified by Rubington, the main technique employed here is one in which the original steel engravings are decontextualized and recontextualized. The intrinsic meaning of the images is radically (and comically) altered by dislocating them from the texts (crime and mystery stories, scientific journals, catalogs) they were originally intended to supplement and completely changing the contextual relationship in which they are now to be viewed. Placed in the service of a new frame of reference, as created by the verbal portion of the novel, the illustrations become humorously incongruous, absurd in their dissonance with the written words and with the reader’s own wonted conception of reality. We see this, for example, where engraved illustrations of mechanical inventions, industrial machinery and medical or dental procedures are said by the narrator to be tools and techniques employed by heroin addicts.

The narrator himself – moralistic, credulous, and highly partisan – is another comic device deployed by the author in Fuzz Against Junk. Combining elevated diction with boyish enthusiasm, the anonymous narrator is the very quintessence of a “square,” an embodiment of all that is conventional, unquestioning, prosaic and pedestrian. His callow commentary ascends to fervent adulation of Sir Edwin Fuzz and the police and descends to indignant vilification of the criminal and subcultural elements whom the forces of law and order oppose. Insensible to his conspicuous lack of nuance or sophistication, the narrator views with undisguised repugnance the “licentious” indulgences, “obscene” literature, “degraded” practices and altogether “brutish” behaviour of “junkies” and “beatniks,” while the hip reader (the audience at whom the book is, of course, aimed) derives wry amusement from the narrator’s zealous naiveté, so at variance with the hipster’s own orientation.

In this regard, much of the book’s satire is aimed at the square world’s reductive caricatures of the drug subculture and the Beat Generation. Junkies are seen by the police as devious degenerates while beatniks are disdained as their depraved accomplices. Briefing his detectives in how to assume their disguises as Beats, Sir Edwin Fuzz instructs them to “bone up on Zen, refrain from washing and let your hair grow … become adept in the Bongo drum … familiarize yourselves with the Beat vocabulary.” And, he adds – further to perfect their impersonations – in order to compose Beat poetry they need only “extract passages from the Farmer’s Almanac and inject obscene words in the right places.”

Humorous exaggeration is also central to Fuzz Against Junk, which depicts a world in which extremes and excesses, manias and obsessions are rife and the outlandish is the norm. An overdose of heroin causes a corpse to swell to gigantic proportions; in their insatiable pursuit of euphoria junkies employ “auricular injections,” “oral incisions,” “osmotic palpitators” “intra-cranium absorption” and opium vapour baths; equipment transported overland from New York to San Francisco by Sir Edwin Fuzz and his detectives to aid in their investigations of “The Man,” includes half-a-dozen batteries of cannon; while detectives in San Francisco resentful of their interloping New York colleagues arm themselves against them with halberds. In common with the book’s disorienting illustrations and equivocal narration, the device of humorous hyperbole effects a disruption of habitual perspectives and perceptions, causing tensile fracturing along safe certainties.

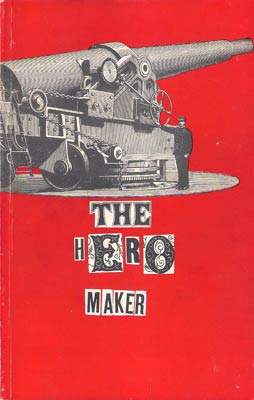

Authority and conformity, credulity and vanity are the targets of satirical humor in the second of the Akbar del Piombo collage novels, The Hero Maker. The novel is set in a dystopian society that has displaced Eros with Thanatos, a society so deeply imbued with a distorted version of the heroic ideal that all of its male citizens nourish no other ambition in life than that of dying heroically. In this community, the Royal Heroic Society is a hallowed institution that – after deliberation by a jury – awards to aspirants the highly coveted official heroic status. This supreme mark of achievement, regarded as conferring immortality on the recipient, can only be granted posthumously, heroism being seen by its very nature to require the decease of the individual (in an heroic manner, of course.) The obvious irony here is that what is regarded as immortality – in the form of a statue or monument or merely an official certificate – necessitates personal annihilation, the untimely sacrifice utterly and forever of all ones potentials and possibilities. A further irony can be seen in the mindless eagerness with which multitudes of young men submit themselves to the various painful preliminary tests and the annual final (fatal) trial and in the agonies of ignominy suffered by the failed candidates for immortality.

Authority and conformity, credulity and vanity are the targets of satirical humor in the second of the Akbar del Piombo collage novels, The Hero Maker. The novel is set in a dystopian society that has displaced Eros with Thanatos, a society so deeply imbued with a distorted version of the heroic ideal that all of its male citizens nourish no other ambition in life than that of dying heroically. In this community, the Royal Heroic Society is a hallowed institution that – after deliberation by a jury – awards to aspirants the highly coveted official heroic status. This supreme mark of achievement, regarded as conferring immortality on the recipient, can only be granted posthumously, heroism being seen by its very nature to require the decease of the individual (in an heroic manner, of course.) The obvious irony here is that what is regarded as immortality – in the form of a statue or monument or merely an official certificate – necessitates personal annihilation, the untimely sacrifice utterly and forever of all ones potentials and possibilities. A further irony can be seen in the mindless eagerness with which multitudes of young men submit themselves to the various painful preliminary tests and the annual final (fatal) trial and in the agonies of ignominy suffered by the failed candidates for immortality.

While, clearly, at one level, the satire in The Hero Maker is aimed at the type of mass-based, militarist-authoritarian ideals that helped to generate two terrible world wars and numerous smaller conflicts in the twentieth century, at a deeper level the book is a critique of the blind submission to culturally inculcated beliefs and values that characterizes the general populace of all societies, large or small, and the competitive conceit that drives individuals to achieve the approbation of their peers and superiors. Gullible, lemming-like, against all common sense and every instinct of self-preservation, the determined aspirants to official immortality rush to their destruction. In a perverse variation of Thorstein Veblen’s notion of conspicuous consumption, in The Hero Maker the price of achieving social prestige is conspicuous self-consumption. By presenting the pursuit of social status in such an extreme form, the essential nature of such a project – silly, sad and futile – is nakedly displayed.

The Hero Maker is abundantly illustrated with skillfully, wittily rendered collages created by the author/artist. Again, the source materials consist of steel engravings from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including graphics drawn from medical texts, illustrated newspapers, and other books and periodicals. Re-enforcing a central theme of the novel – mindless conformity to absurd social norms – a recurrent motif among the collages of The Hero Maker is that of the human head, its deformity, its replacement, injury or absence. The collages depict various objects taking the place of heads, children’s heads on adult bodies, wounded heads, obliterated heads, heads separated entirely from the body and heads impaled, animal heads on human bodies, heads replaced with helmets, microcephalic heads, and heads with faces that are grotesque masks. Clearly, with heads such as these, critical thinking is out of the question.

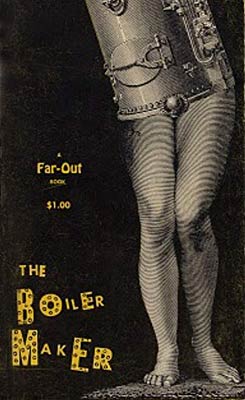

The contemporary art world and the Hollywood film industry in their manifold absurdities are the immediate objects of ridicule in the third of Norman Rubington’s collage novels, The Boiler Maker. But, a deeper theme of the novel is the way in which language and image mediate our perception of reality, shaping our beliefs and attitudes. The “boiler maker” of the title refers not to the shot-and-a-chaser combination cherished by earnest tipplers but to an avant-garde sculptor named Luigi Fazzoletto, also known as “Izit,” founder and principal exponent of the “Mechanist Movement,” whose metal constructions are indistinguishable from industrial machinery.

The contemporary art world and the Hollywood film industry in their manifold absurdities are the immediate objects of ridicule in the third of Norman Rubington’s collage novels, The Boiler Maker. But, a deeper theme of the novel is the way in which language and image mediate our perception of reality, shaping our beliefs and attitudes. The “boiler maker” of the title refers not to the shot-and-a-chaser combination cherished by earnest tipplers but to an avant-garde sculptor named Luigi Fazzoletto, also known as “Izit,” founder and principal exponent of the “Mechanist Movement,” whose metal constructions are indistinguishable from industrial machinery.

Attracting the patronage and advocacy of the wealthy art collector Baron Hector Kleinschnitt, Izit’s massive mechanical pieces initially incite opprobrium and censure, then inspire widespread imitation, and finally achieve critical acclaim and international renown. A highly fictionalized feature film of Izit’s life is undertaken by a major Hollywood studio and while the film proves to be popular and financially successful, it causes both the Baron and Izit to be attacked by a rabble of irate sculptors who destroy the Baron’s mansion and art collection, while Izit – viewed by his colleagues as having sold out to commercialism – is left destitute and forever unwelcome in the art world.

The Boiler Maker is a witty critique of the modern art world’s susceptibility to gimmickry and jargon, its faddishness, fractiousness and fickleness. The book also casts a mordant eye on the schlock-blockbuster syndrome afflicting the film industry, the tasteless readiness of film writers and directors to misrepresent actual lives and events through melodrama and lurid spectacles. A common denominator between the two media – art and film – is to be found in what is viewed as a shared betrayal of their vital potential as vehicles of vision, being given over instead to devising false and shallow versions of what is real and of worth in the world. Images that could serve to elevate or liberate minds and spirits, serve instead to deceive.

In such deception language is seen to be a cunning accomplice. The Boiler Maker demonstrates how words impose specific interpretations upon objects and events, distorting and disguising, manipulating and misleading. “Mechanism,” for instance, as a theory of art confers upon what are manifestly mere machines the status of sculptures. Considered as works of art, the machines are then much admired by art critics for their “absence of artifice,” while the sculptor is lauded for the “profound dialectic in his modulation of the interior voice.” Similarly, the titles assigned to individual Mechanist works, such as “Sex Drive,” “Hot Bitch,” and “Function of the Orgasm” cause them to be reviled by the guardians of decency and shunned by the public, though without their suggestive titles the “sculptures” would be seen as merely insipid and trivial. A further example of words defining reality occurs when the writers concocting a sensationalistic screenplay for the proposed film of Izit’s life, feel compelled first to find a suitable title for the film. They decide upon “The Largest Plush in the World,” a nonsensical, if titillating, phrase which bears no relation to the actual plot of the film, while their screenplay, inspired by the title, bears no relation whatever to Izit’s actual life. Whatever worthy roles language and the arts might once have served in the world, expressing spiritual or philosophical truths, communicating complex feelings and states of mind, exploring perception or creating beauty, in the world of The Boiler Maker those noble potentials are shown to have been suffocated under an avalanche – both verbal and visual – of sham, cant and imposture.

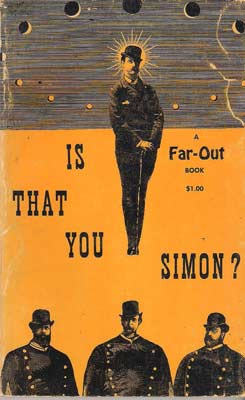

The theme of the deployment language as an instrument to seek influence or authority over reality is also prominent in Is That You Simon? (1961). When Simon De Joy, a watch and clock manufacturer, launches himself into outer space aboard a homemade rocket (misnamed Zen) the varied interpretations of the event by the world’s newspapers and citizens serve to illustrate the ways in which unaccustomed phenomena are appropriated and incorporated into pre-existing ideational patterns and ideological attitudes. In Italy, for example, L’Osservatore newspaper views Zen “not as a rocket but as a warning,” while L’Unitá comments “Zen will pass just as capitalism will pass.” Preoccupied with their own affairs, French newspapers consign the event to their back pages. Similarly, blasé New Yorkers ignore the occasion altogether, while “along the Mississippi, it was hailed as a symbol of the strength of the Union.” Sophisticated San Franciscans can’t be bothered to view the passage of the rocket through the night sky, preferring to watch it on television. Predictably, comment from the government of the U.S.S.R. interprets the occurrence in terms of Marxism. Ultimately, a cigar manufacturer in the U.S. purchases exclusive rights to De Joy’s outer space communications, exploiting a remarkable historic event for commercial purposes.

The theme of the deployment language as an instrument to seek influence or authority over reality is also prominent in Is That You Simon? (1961). When Simon De Joy, a watch and clock manufacturer, launches himself into outer space aboard a homemade rocket (misnamed Zen) the varied interpretations of the event by the world’s newspapers and citizens serve to illustrate the ways in which unaccustomed phenomena are appropriated and incorporated into pre-existing ideational patterns and ideological attitudes. In Italy, for example, L’Osservatore newspaper views Zen “not as a rocket but as a warning,” while L’Unitá comments “Zen will pass just as capitalism will pass.” Preoccupied with their own affairs, French newspapers consign the event to their back pages. Similarly, blasé New Yorkers ignore the occasion altogether, while “along the Mississippi, it was hailed as a symbol of the strength of the Union.” Sophisticated San Franciscans can’t be bothered to view the passage of the rocket through the night sky, preferring to watch it on television. Predictably, comment from the government of the U.S.S.R. interprets the occurrence in terms of Marxism. Ultimately, a cigar manufacturer in the U.S. purchases exclusive rights to De Joy’s outer space communications, exploiting a remarkable historic event for commercial purposes.

Even as language can be used as a tool in an attempt to impose predetermined conceptual structures upon reality, so also in the novel do we see science and technology seeking to shape the circumstances and conditions of the material world. The watches and clocks manufactured by De Joy’s plant, for instance, can be seen as part of an ongoing scientific endeavour to impose arbitrary, artificial measurement upon the fluid and elusive phenomenon of time. In a similar self-confident spirit, a host of scientists and engineers, IBM computers, the Closewitz Laboratory, the Army and the Navy and the Department of Outer Space, all strive repeatedly and in vain to effect the launch of an unmanned rocket into outer space. Significantly, when De Joy accomplishes such a launch and even succeeds in landing a spacecraft on the moon, his triumph is attributable – not to scientific rigor or technological expertise – but rather to a series of mistakes, mishaps and inadvertencies. In this way, the novel suggests the limits of human will and abilities in fashioning outcomes. Ultimately, chance trumps causality. And when it is confirmed by De Joy that already in the 12th century B.C. an expedition to the moon was achieved by Ramesses II – a theory long dismissed in scientific circles – modern science and technology suffer a decided and definitive discomfiture.

Running through Is That You Simon? there is a murky undercurrent of conflict and aggression, expressed in every human sphere from the political to the personal. Underlying the events of the story is the rancorous Cold War rivalry between the U.S.A. and the U.S.S.R. Additionally, there is the petulant competition between branches of the American armed services, jealous strife among members of the scientific community, and vindictive personal betrayals. Evidence of human aggression and self-assertion becomes more explicit in Moonglow (1969) a tale which begins with one atomic war and ends with another, while in the interim between the two conflicts malice and hostility flourish at every level. Moonglow is the tale of Harry Moonglow, a child conceived at the very instant of the outbreak of World War III. As a consequence of having been exposed to high levels of radiation during gestation, Harry is a singular genetic mutation, one whose physical attributes are constantly in flux, as he involuntarily assumes the facial features and body shapes of a diverse array of human types. Bullied during his boyhood by other children and driven from home by his own parents, in bitterness Harry becomes a thief, before being recruited by the C.I.A. as a spy, an occupation for which he proves to be admirably suited.

The immediate post-apocalyptic era depicted in Moonglow is one in which human aggression persists undiscouraged and undeterred by the calamitous events that have just taken place. Survivors of the war take advantage of the chaos attendant upon mass devastation in order to pursue with impunity personal vendettas. The governments of the world quickly resume their antagonisms and “the Golden Age of the Spy” arises. Ultimately, however, due to having been made redundant by a super computer, the spies turn on their former masters, on society at large and finally on each other, committing random acts of terror, turning the cities into battlefields. In the midst of the murder and mayhem, someone contrives to unleash nuclear strikes and the world is once more reduced to rubble and radioactive ruins.

The immediate post-apocalyptic era depicted in Moonglow is one in which human aggression persists undiscouraged and undeterred by the calamitous events that have just taken place. Survivors of the war take advantage of the chaos attendant upon mass devastation in order to pursue with impunity personal vendettas. The governments of the world quickly resume their antagonisms and “the Golden Age of the Spy” arises. Ultimately, however, due to having been made redundant by a super computer, the spies turn on their former masters, on society at large and finally on each other, committing random acts of terror, turning the cities into battlefields. In the midst of the murder and mayhem, someone contrives to unleash nuclear strikes and the world is once more reduced to rubble and radioactive ruins.

In addition to its grimly comic critique of inveterate, obdurate, perverse human destructiveness, Moonglow also addresses issues of technology and language. The novel makes clear the folly of developing technologies such as artificial intelligence and nuclear weapons that ultimately serve only to diminish and destroy humankind, as if our aggressive and self-aggrandizing impulses were a kind of death wish in disguise. Significantly, the story itself is related by “OSP ex-military computer (Orthophonic Syntax Pullulator.)” Apparently, in the aftermath of the second atomic war, computers have largely replaced human beings. As in The Boiler Maker and Is That You Simon? the failure of language to communicate effectively or truthfully is again a theme in Moonglow. We see, for example, how a dire threat uttered by a French policeman is wildly mistranslated, transforming a menacing declaration into an innocuous (if incongruous) question. We witness, too, how at one point Harry is censured by his superiors when the word “brides” is misconstrued as “bribes.” Indeed, throughout the novel the words spoken by figures in the story are frequently without any relation to the situations in which they find themselves. (An innovation added to Rubington’s collage illustrations in Moonglow is the use of speech or word balloons.) To cite but one such instance, when Harry is being arrested for loitering in the Place St. Michel, he inquires of the arresting officer: “I can have all the cars I ever wanted?” The world of Moonglow is one of false appearances, pseudonyms, impersonations, replicas, non sequiturs and subterfuges, a world in which in every word and at every turn there would seem to be plentiful traps for the unwary.

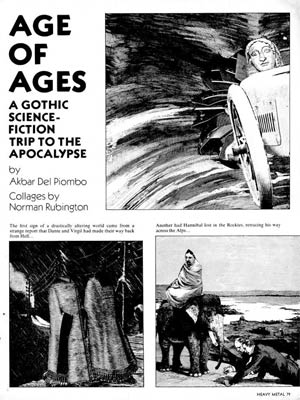

The theme of cataclysm is also central to the sixth and last of Akbar del Piombo’s collage novels, Age of Ages: A Gothic Science Fiction Trip to the Apocalypse, wherein the human situation slips by hideous increments into an abyss of chaos, madness, violence and destruction. Taking as its point of departure the dystopian world depicted in George Orwell’s 1984, Age of Ages opens as the repressive reign of Big Brother comes to an end with his death and is succeeded and superceded by the tyrant’s malign younger sibling, Little Sister. With the aim of attaining absolute control over the minds of her subjects, the new ruler effects an unholy alliance between the most advanced surveillance technology, neurotechnology and the forces of the occult, enlisting in furtherance of her project a motley body of scientists and technical experts, witches, spirit mediums, sorcerers and soothsayers.

The theme of cataclysm is also central to the sixth and last of Akbar del Piombo’s collage novels, Age of Ages: A Gothic Science Fiction Trip to the Apocalypse, wherein the human situation slips by hideous increments into an abyss of chaos, madness, violence and destruction. Taking as its point of departure the dystopian world depicted in George Orwell’s 1984, Age of Ages opens as the repressive reign of Big Brother comes to an end with his death and is succeeded and superceded by the tyrant’s malign younger sibling, Little Sister. With the aim of attaining absolute control over the minds of her subjects, the new ruler effects an unholy alliance between the most advanced surveillance technology, neurotechnology and the forces of the occult, enlisting in furtherance of her project a motley body of scientists and technical experts, witches, spirit mediums, sorcerers and soothsayers.

And if such intrusive oppression were not itself sufficient tribulation for humankind, signs of “a drastically altering world” begin to manifest themselves. Suddenly, evidence of reverse evolution becomes apparent in the animal kingdom, certain of the dead return to life, and an ominous double moon appears in the night sky, whereafter madness and murder ensue and society is swept with desperate fads and cults, suicides and extremes of sensual indulgence. Al Capone is officially declared to have been a national hero and a museum is dedicated to his achievements, the Golden Calf reappears as an object of veneration and the Whore of Babylon makes her portentous entrance. Meanwhile, oblivious to consequences, scientists continue to contribute to the general decline in social order and morals by creating a myriad of monstrous new life forms, discovering new euphoria-inducing substances, and engineering life-like bio-mechanical sex-robots designed to cater to every sexual taste and preference. Even the illustrious Sir Edwin Fuzz – urgently solicited by the authorities to assist in official investigations into the grim and ever deteriorating world situation – is at loss to find an explanation or to suggest a remedy. Thus unchecked by any human restraint or resource, the apocalypse advances inexorably toward havoc, collapse and utter devastation.

Might it be the case that in this instance Sir Edwin Fuzz is unable to discover a perpetrator to the crime under investigation because the solution lies beyond the purview of criminal science and resides, instead, in the realm of the metaphysical? Is the apocalypse in some unknown way a response to human folly and depravity? Or is the extraordinary wave of debauched and destructive human behaviour that engulfs the world a consequence of the apocalypse? Or is there an implication here that order in the natural world is not immutable but at best tenuous and temporary? Certainly, the sudden erratic nature of the physical world (reverse evolution, the double moon, resurrections, etc.) may be seen to be mirrored in the outbreak of lawless human behaviour. The civilized world is suddenly assailed to an unparalleled degree by uncontrolled compulsions given untrammelled expression: the pursuit of power (Little Sister and her minions,) of plunder (criminal gangs and sundry muggers,) and pleasure (the erotically obsessed sensualists with their sex-robots.)

The collages in Age of Ages portray a world in which conventional reality is no longer stable but ever shifting. Dissimilar phenomena and even temporal periods collide, the incredible invades the ordinary: ancient gods drive modern racing cars, fish swim placidly through the air, extinct animals invade homes and buildings, roman gladiators mug passersby on the streets of New York city, smiling nudes recline before an onrushing locomotive, spear-carrying armour-clad warriors stand guard at the Pentagon, an orbiting open air space colony passes above a giant antique Victrola, sanitation workers exorcise demons from a victim of possession, an automated trashcan deflowers a young woman. Certitude, order and pattern are overthrown and the world stands revealed as tentative, equivocal, a farcical flux, a comic nightmare, an unsolved riddle.

At one dramatic moment in Age of Ages, Sir Edwin Fuzz wonders aloud: “Has the battle for men’s minds been won? And if so, by whom?” The question might be said to resonate back through all the Akbar del Piombo collage novels an underlying theme of which is human folly in its myriad forms. Religion, philosophy and ideals of personal conscience and social justice all alike bid us to seek the good and the true, but, as history and biography can attest, all too often our best intentions are undermined or overwhelmed by forces from without and from within, forces that seek, instead, to diminish our integrity, our individual autonomy and personal agency and, in effect, seize control of our minds. Such forces are the targets of satirical critique in the del Piombo collage novels: unquestioned conventions and received opinions, human vanity and aggression, status seeking, conformity, hedonism and avarice, narrow moralism, and a gullible trust in authority, technology, language and consensus reality.

A number of motifs in the collage novels can be seen to reflect the radical instability and accelerating change of the era through which the author and artist Norman Rubington lived: the Great Depression, the rise of fascism, World War II, the Korean War and the Cold War, postwar affluence and the advent of television, computers and automation, mass communications, mass marketing and mass consumption, the growth of large bureaucracies and large corporations, the space program, atomic weapons and the threat of nuclear annihilation. To alert and reflective minds of Rubington’s generation the world must have seemed erratic, precarious and unpredictable in the extreme, a world in which the individual was under siege from multiple systems. Hence, I think, the distrust of science and authority, of fads and mass movements and of linguistic and cultural codes that may be seen to pervade the Akbar del Piombo collage novels. Similar anxieties are to be found in the works of fellow satirists of Rubington’s generation, including Terry Southern, William S. Burroughs, Joseph Heller, Kurt Vonnegut Jr. and Lenny Bruce.

Even among fellow satirists and hip humourists of his generation, Norman Rubington’s collage novels are notable for their unique combination of the verbal and the visual, as well as for the distinctive wit and wild sense of the absurd that inform them. (E.g. Age of Ages in which “mutiny aboard a one-man submarine” occurs.) It is discouraging to discover that at present all of the Akbar del Piombo collage novels are out-of-print. This is regrettable since they are very far from being dated artifacts of the postwar hip sensibility but are, instead, perennially pertinent satires, imbued with an unruly and hallucinatory humour. It is to be hoped that soon some enterprising small press will rescue them from the undeserved oblivion into which they seem now to have fallen.

Notes

1 Written by Norman Rubington under the name of Akbar del Piombo: Who Pushed Paula? (1956), Skirts (1956), Cosimo’s Wife (1957), The Traveller’s Companion (1957) and The Fetish Crowd (1959.) All published by the Olympia Press, Paris. There is a brief account of Rubington’s early years in Paris in Left Bank, Right Bank by Joseph Barry, London: 1952, pp. 71-72. Barry writes of Rubington as being “perhaps the most talented of the younger American artists in Paris” p. 71.

2 With regard to viewing Rubington’s collage novels as speculative fiction, the only review of the Akbar del Piombo books that I have been able to locate appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, vol. 24, no. 2, February 1963: “Books: Fuzz Against Junk, Is that you Simon?, The Boiler Maker, The Hero Maker,” by Avram Davidon, pp. 33-34.

3 Fuzz Against Junk by Akbar del Piombo, Paris: Olympia Press, 1959; New York: Citadel Press, 1961; London: New English Library, 1966; New York: Beach Books, 1969; Rolling Stone nos. 33, 34, 35, 36, 1969. A French translation titled L’Anticame was published in Paris by La Grande Séverine in 1960. The American slang term “fuzz” used to designate the police was widely used among criminals, hobos and carnival workers for several decades before gaining currency among the hipsters and Beats of the 1950s. See Flappers 2 Rappers: American Youth Slang by Tom Dalzell published Merriam-Webster, Springfield, Mass. 1996, pp. 91,140.

4 The Hero Maker by Akbar del Piombo, Paris: The Olympia Press, 1960. Reprinted bound with Fuzz Against Junk, London: New English Library, 1966.

5 The Boiler Maker by Akbar del Piombo, published simultaneously in Paris by The Olympia Press and in New York by The Citadel Press, 1961.

6 Is That You Simon? by Akbar del Piombo, published simultaneously in Paris by The Olympia Press and in New York by The Citadel Press, 1961.

7 Moonglow by Akbar del Piombo, New York: Beach Books, 1969.

8 Age of Ages: A Gothic Science Fiction Trip to the Apocalypse appeared in serial form in Heavy Metal April 1977, pp. 79-82; May 1977, pp. 66-68; June 1977, pp. 69-71; August 1977, pp. 53-56; and February 1978, pp. 69-72.

NOTES:

Yvonne Bond says

I have The Hero Maker and The Boiler Maker, which I bought in San Francisco CA where I grew up — possibly at the City Lights book store.

How much are they worth now?