Before the appearance of Leaves of Grass, Walt Whitman kept notebooks in which he wrote sketches for lines of poetry. As Andrew Higgins points out in Art and Argument: The Rise of Walt Whitman’s Rhetorical Poetics, 1838-1855, Whitman used these notebooks to grapple with democracy, slavery, transcendentalism, and spiritualism. Higgins also notes, “But he did not yet understand how to make the pieces cohere. That coherence would [. . .] not fully appear until the final notebooks: ‘Poem incarnating the Mind’ and ‘albot [sic] Wilson’” (159). This means that the “Talbot Wilson” notebook was an important and necessary notebook in the development of Leaves of Grass. Higgins, though, mainly focuses on the importance of the content in the notebook towards the development of Leaves of Grass. However, in the “Talbot Wilson” notebook, Whitman not only drafted lines with content that would later appear in Leaves of Grass, but he also left markings to remind himself of what he needed to revise and expand on at a future time.

These em dash and ellipsis markings Whitman wrote in the notebook are significant because they have not received enough scholarly attention, and because the markings are used in a unique manner. Typically, in one’s everyday writing, an em dash can be used in manner like a comma, and sometimes like parenthetical markings if there are two of them. In poetry, they also often indicate a bridge or leap in thought. An ellipsis, on the other hand, indicates an omission of thought or words, and if it occurs at the end of a sentence, then it indicates the thought continues on or trails off. An ellipsis can also to indicate a hesitation or pause. Whitman will build on this elliptical pause when he uses it as a marker to indicate a place to revise. More importantly, the notebook markings also indicate that early on Whitman knew he would need a long line to accommodate thoughts he knew needed development but that he wasn’t able to fully develop at the time of writing in the notebook. In the “Talbot Wilson” notebook, Whitman left marks for the future – the future of the long line and the future of Leaves of Grass.

In this paper, I will provide some background about the notebook to show its close historical proximity to the 1855 first edition of Leaves of Grass (which has been under dispute), demonstrate how the markings generally behave in the notebook, compare how similar markings behave in the 1855 edition and other editions of Leaves of Grass, then show how the markings in the “Talbot Wilson” notebook were revised and expanded in later editions of Leaves of Grass. I do this to differentiate the markings in the “Talbot Wilson” notebook from markings in the various editions of Leaves of Grass and to provide evidence of the markings in the “Talbot Wilson” notebook acting as notations for revision, expansion, and developing Whitman’s long-lined poetics.

The “Talbot Wilson” Notebook

Between 1847 and 1855 something happened to Whitman that transformed him from an everyday poet and journalist into the genius poet that today’s readers are familiar with in Leaves of Grass. Scholars have looked to his notebooks for evidence of what prompted this change and to “see more clearly the development of Leaves of Grass” (Higgins, “Wage Slavery” 53). One notebook, the “Talbot Wilson” notebook, is important in helping to determine the transition and development because in this notebook Whitman drafts out his long lines, and many versions of these lines that will later appear, though revised, in Leaves of Grass.

Early scholarship erroneously dated the “Talbot Notebook” notebook to 1847. If that date was correct, then it means Whitman had an early start on his long-line poetics, which as Matt Miller points out, “was probably the single most important factor accelerating his development” (2) as poet. This 1847 date would also mean Whitman had eight years to work on developing his new poetics, and his shift from an amateur or immature poet and journalist to the genius poet of Leaves of Grass was gradual. However, this date is not correct, as it confuses an “1847” marking on the first page of the notebook as indication of the date Whitman wrote in the notebook, but Miller shows how scholars determined Whitman was just recycling old notebooks, and he didn’t write in the “Talbot Wilson” notebook until well after 1847.

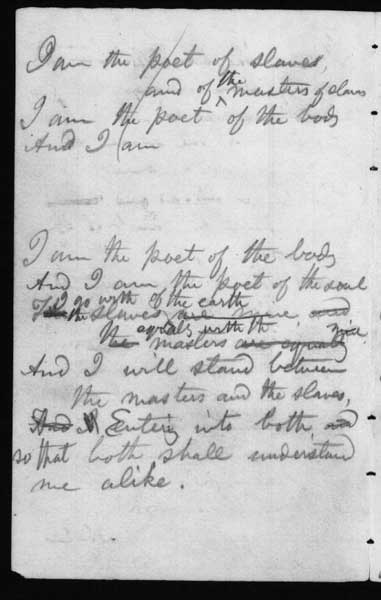

In “Wage Slavery and the Composition of Leaves of Grass: The ‘Talbot Wilson’ Notebook,” Andrew Higgins shows how Whitman’s use of “racial imagery” (53) in other notebooks and in the “Talbot Wilson” notebook helps narrow down the composition date. Higgins points out how David S. Reynolds shows that Whitman’s “‘discovery’ of poetry sprang from his contemplation of the slave issue” (54), and quotes Betsy Erkkila, who claims, “When in his notebook, Whitman breaks for the first time into lines approximating the free verse of Leaves of Grass, the lines bear the impress of the slavery issue” (54). The “Talbot Wilson” notebook is even more transitional than the slavery issue, as it is here where Whitman transitions from racial imagery to body imagery. For instance, on page 70 of the Library of Congress #80 digitized version of the “Talbot Wilson” notebook, Whitman wrote:

I am the poet of slaves,

and of the masters of slaves

I am the poet of the body

And I am

(Folsom’s transcription, “I am the poet of slaves”)

These lines have both “slaves” and “body,” and there is a hanging indent, which appears indicative of Whitman thinking of a long line, but the notebook page is too narrow to contain such a long line, so he uses the hanging indent. What is important, though, is Whitman strikes a line down across this stanza, and then begins a new stanza below it on the same page.

I am the poet of the body

And I am the poet of the soul

TheI go with the slaves of the earthare mine and

The equally with the mastersare equally[illegible]

And I will stand between

the masters and the slaves,

And IEntering into both,and

so that both shall understand

me alike.

(Folsom’s transcription, “I am the poet of slaves”)

In this revision, Whitman privileges “body” and “soul” first, or as Higgins says, “Whitman begins to de-emphasize the slavery metaphor [. . .] and placing the body/soul binary before the slavery/master binary” (“Wage Slavery” 62). The body and soul become the important metaphor and acts as mediator between slave and master. Again, there is a hanging indent, which suggests that lines three through six, if on a wider piece of paper, could be written as: “I go with the slaves of the earth equally with the masters / And I will stand between the master and the slaves.” The lines act as or contain grammatical units. In later editions of Leaves of Grass, where “I am the poet of the body / And I am the poet of the soul” lines appear in “Song of Myself” (either as two lines in the 1855 edition or as one line in the 1892 Deathbed Edition), the image of slavery is no longer present. This shift from slavery imagery coupled with the markings for longer lines, thus locates the “Talbot Wilson” notebook very close to the publication of the first edition of Leaves of Grass in 1855, which Higgins clearly shows, and which “in the words of Alice L. Birney of the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, ‘a more likely date for these drafts — with prose breaking into poetry — is 1853-54’” (53).

Higgins, Miller, and Birney suggest that the “Talbot Wilson” notebook shows Whitman’s shift in poetic content, imagery, and metaphors as indicators of a transitional stage in his poetry. What they don’t examine are the markings also accompanying Whitman’s transition of “prose breaking into poetry.” On 29 of the notebook’s 133 pages, Whitman uses the markings of ellipses and em dashes in specific manners, and there are two ways to read the use of these markings in the “Talbot Wilson” notebook: how they used in the notebook as its own text or manuscript and independent of what Whitman will later write, and how they are used as markings to remind Whitman to revise later drafts of the poem.

Markings in the “Talbot Wilson” Notebook

The em dash, which is a marking longer than a hyphen, appears on 29 pages of the notebook. Sometimes a notebook page will have only one em dash, but many times a page will have multiple em dashes. Despite how frequently the marking occurs on the page1, it tends to have one of two uses: to mark the end of a poem or to mark that an extended, clarified, or qualified definition will follow, which is often done by coupling the em dash with anaphoric words.

For example, page 21 concludes a long text that begins on page 19, where the first appearance of any significant text appears in the notebook. Scanned page 1 is the cover to the notebook, page 2 contains some addresses plus the inscription “Talbot Wilson” (which is how the notebook received its name), and page 3 contains some names, numbers, and a sentence written in French. Pages 4-18 are torn edges of pages. Page 19 begins with “Be simple and clear. – Be not occult.” The writing, which may be a poem or just written out thoughts, continues on to page 20, and finishes half way down page 21, with:

caoutchour[??] and strong as

iron — I wish to see

American you seen[??]

the workingmen, carry their

selves with a high horse

—

(My transcription)

Nothing follows the em dash, and thus it appears as a marker for the end of a thought or a poem. To show just one more example, consider the shorter piece on page 31:

Never speak of the soul

as any thing but intrinsically

great. — The adjective affixed[??]

to it must always testify

greatness and immortaliy and

purity. —

(My transcription. Whitman incorrectly spells “immortality.”)

These lines are clearly instructions to Whitman as to how to approach using soul in his poems, and the thought ends with an em dash.

However, another em dash also appears between the two sentences on this page, and it behaves differently than the final em dash. As mentioned earlier, the other use of the em dash is to indicate that a qualifier will follow. In this case, “soul” is qualified. Preceding the em dash, Whitman makes a note to remind himself how to use or later develop “soul” in his poems, and it must always be fundamentally great. This is also an instance of Whitman thinking about what he needs to do in the future with his poetry. One could consider the em dash a language-based bread-crumb trail leading into the future. What follows the em dash are also notes on how to use “soul” or how to qualify or modify it. When “soul” is modified with an adjective, it must also indicate immortality and “purity.” He builds on his definition or use of “soul” after the em dash. He leaves more bread crumbs. While this passage is not a poem, Whitman thinks about his use of language in his poetry, or at least how he will use “soul” in his poetry. To make this observation clearer, I want to look at pages 28 and 29. First page 28:

The soul or spirit

transmutes itself into all

matter — into rocks, and

can [illegible] live the life of a

rock — into the sea,

and can feel itself the sea —

into the oak, or other

tree — into an animal,

and feel itself a horse,

a fish, or a bird —

into the earth — into the

motions of the suns and

stars —

A man only is interested

in any thing when he identifies

himself with it — he must

himself be whirling and speeding

through space like the planet

(Folsom’s transcription, “The soul or spirit”)

And page 29:

Mercury — he must be

driving like a cloud —

he must shine like

the sun — he must

be orbic and balanced

in the air like this

earth — he must crawl

like the pismire — he

must

— he would be growing

fragrantly in the air, like

a the locust blossoms —

he would rumble and

crash like the thunder

in the sky — he would

spring like a cat on his

prey — he would splash

like a whale in the

(Folsom’s transcription, “Mercury — he must be”)

Versions of these pages will later appear in section 7 of “Enfans d’Adam” in the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass, in “We Two — How Long We Were Fool’d” in the 1867 and 1872 editions, and then in “We Two, How Long We Were Fool’d” in the 1881-82 edition and the 1891-92 Deathbed edition of Leaves of Grass. However, versions of these excerpts do not appear in the first edition from 1855.

Before getting to the revised versions, the em dashes in the notebook pages are again marking a place to qualify a word or idea. On page 28, the em dash marks the various types of “matter” the soul or spirit can transmute into, such as rock, sea, fish, or bird. The em dash mark can then be read as something like, “this is what I mean by ‘matter’.” On page 29, the em dash behaves in a similar way as it indicates that what follows the em dash further defines what precedes the em dash, which is “Mercury.” As a result, “Mercury” must be a cloud, the sun, the earth in space, locust blossoms, etc.

Accompanying the em dashes on both pages are repeated words, too. On page 28, the repetition is with “into.” Because the word is repeated after an em dash, one might hear it as an anaphoric device, which means it would be the first word of the line, and if laid out on the page, it might look like this:

The soul or spirit transmutes itself into all matter —

into rocks, and can [illegible] live the life of a rock —

into the sea, and can feel itself the sea —

into the oak, or other tree —

into an animal, and feel itself a horse, a fish, or a bird —

into the earth —

into the motions of the suns and stars —

Each line is allowed to expand, as it is not confined to the narrow width of the notebook page. When Whitman returns to these lines and revises them in later editions of Leaves of Grass, he further expands them. What I want to show here is how Whitman may have started to think about the line as a long line, but the narrow notebook pages would not let him score such long lines without using some type of notation or marking to tell himself to later expand, and in this case, the marking is the em dash. I’ll return to this after looking at some early uses of the ellipses.

Three pages have four-dot-ellipses markings – pages 113, 114, and 115. Page 54 also has an ellipsis, but it’s hard to discern how many dots there are, as there are at least three, maybe five, and maybe six. Overall, four pages of the “Talbot Wilson” notebook have an ellipsis marking. The ellipsis marking appears to work in a similar fashion as the em dash. For instance, on page 113, Whitman wrote:

Justice ,

does not defineis not varied as

upontempered the in passage of[illegible]

laws by legislatures . —The

legistlatures cannotsettlealter

it any more than they can

settle love or the attraction of gravity or pride. —

The quality of justice

is in the soul. — It is

immutable . . . . it remains

through all times and

nations and administrations[??]

. . . . it does not depend

on majoritiesandand

minorities . . . . Whoever

violates it [illegible]shall

fullpays the penalty

just as certainly as he

who violates the attraction

(My transcription)

Down this page and over the text run two parallel lines. Versions of some of these lines also appear on the last page of the first edition of Leaves of Grass, which I will look at later. In the notebook, though, “the quality of justice” is clarified after the ellipsis markings, and it also uses anaphora with “it.” Interesting to note, though, is the sudden switch from em dash to ellipsis, while the behavior of both markings is similar — a qualifier of what preceded the markings. This switch will occur on the next two pages, too. Questions that arise are: why does Whitman use the ellipsis sparingly here? use the ellipsis frequently in the first edition? and then completely eradicate the use of the ellipsis by the time of the Deathbed edition? In fact, in between the first edition and the final edition, the ellipsis is rarely used.2> In addition, the ellipsis marking is used differently in the prose preface to the first edition of Leaves of Grass than in the poems.

Markings in Leaves of Grass

The untitled preface to Leaves of Grass is a long, prose essay that does not move in the typical linear, smoothly connected pace of an essay. It does, however, move forward, and ideas do progress, but it moves closer to the way a person thinks in the head, or how a poem thinks. The preface makes leaps in thinking and thinks associatively. Much of this thinking occurs with the ellipses and the em dashes. Within the preface, an ellipsis often acts as an indicator of a small jump in thought, sometimes it acts like a comma, and sometimes as an indicator that a list will begin (but a list where each listed item is more than a word or two — a phrasal list — and a list where anaphora is employed). The em dash, however, indicates a qualifier will be supplied or a thought will be extended or clarified, which often acts like a non-restrictive clause, and often the em dash includes anaphora, too.

In the preface’s opening paragraph, the ellipses jump, list, and work as part of an anaphoric movement.

America does not repel the past or what it has produced under its forms or amid other politics or the idea of castes or the old religions . . . . accepts the lesson with calmness . . . is not so impatient as has been supposed that the slough still sticks to opinions and manners and literature while the life which served its requirements has passed into the new life of the new forms . . . perceives that the corpse is slowly borne from the eating and sleeping rooms of the house . . . perceives that it waits a little while in the door . . . that it was fittest for its days . . . that its action has descended to the stalwart and wellshaped heir who approaches . . . and that he shall be fittest for his days. (iii)

The anaphora is easy to see and hear, as it occurs with “. . . perceives” and “. . . that.” A moment of thought, or an elliptical thought, also occurs in the ellipses. That is, the ellipses elides the subject of the sentence, as one could replace the ellipsis with a period followed by “America” to form a complete sentence. So instead of:

. . . perceives that the corpse is slowly borne from the eating and sleeping rooms of the house . . . perceives that it waits a little while in the door

it could read:

America perceives that the corpse is slowly borne from the eating and sleeping rooms of the house. America perceives that it waits a little while in the door.

The reader participates with Whitman as he thinks on the page. To help clarify this point, consider W. S. Merwin. The contemporary American poet W. S. Merwin in response to a question that asked him why he doesn’t use punctuation in his poems said something like, “Because the mind doesn’t think in punctuation.” Similarly in the preface, the reader is in the quick moving mind of Whitman, who at times does not think in subjects, or maybe the subjects are just assumed, as he is more concerned with moving on to the verb in order to create velocity or mimic the velocity of thought.

Another example of the ellipsis marking occurs midway through the preface, where Whitman writes:

His love above all love has leisure and expanse . . . . he leaves room ahead of himself. He is not irresolute or suspicious lover . . . he is sure . . . he scorns intervals. His experience and the showers and thrills are not for nothing. Nothing can jar him . . . . suffering and darkness cannot – death and fear cannot. To him complaint and jealousy and envy are corpses buried and rotten in the earth . . . . he saw them buried. (9)

Here it appears Whitman is defining his use of the ellipsis as a place of “expanse,” a place to leave “room ahead of himself,” or a bread crumb notation to the future Whitman. As Miller points out, as the first edition of Leaves of Grass was going to print and the type was being set, Whitman wrote a note to “Andrew Rome, a small-job Brooklyn printer” (who was printing Leaves of Grass) (54). Within the note, Whitman reveals “that he was making major changes in the structure and presentation of his entire book. Because the preface is not mentioned, it is clear that the preface was indeed, as Whitman later claimed, ‘written hastily while the first edition was being printed’” (54). Whitman didn’t have time to expand his thoughts, and perhaps, he hoped the reader would be able to fill in the blanks, or as Keith Wilhite notes:

Writing becomes a process of creating absent centers, and the scene of writing emerges in the poetry as a site to be filled and possessed by the subjectivity of the reader. That is to say, at the scene of writing, Whitman’s mind is full of absences – not only the absence of words yet lacking from the language, but the absences or gaps encoded in the text and upon which his poetic project depends. (923)

This “site to be filled and possessed by the subjectivity of the reader” might also be the subjectivity of the future reader of Walt Whitman.

These gaps to be filled in at a later time not only appear in the ellipses but also in the em dashes, though there aren’t nearly as many em dashes as ellipses in Leaves of Grass. Within the preface, the em dashes mark places of qualification, just like in the “Talbot Wilson” notebook. For instance, in the third paragraph of the preface, Whitman praises the genius of the common American people and says:

Their manners speech dress friendships — the freshness and candor of their physiognomy — the picturesque looseness of their carriage . . . their deathless attachment to freedom — their aversion to anything indecorous or soft or mean — the practical acknowledgment of the citizens of one state by the citizens of all other states — (Leaves 1855, iii)

After each em dash is a qualifier describing what the American genius is or how it acts. This em dash qualifying continues for nine more lines of prose.

Returning to the use of the ellipsis marking, in the Leaves of Grass poems (as opposed to the preface), the ellipsis behaves differently, yet again. In the poems, the ellipsis marks something similar to a comma or a notation for a breath. For instance, in the fifth “Leaves of Grass” poem, Whitman writes:

This is the female form,

A divine nimbus exhales from it from head to foot,

It attracts with fierce undeniable attraction,

I am drawn by its breath as if I were no more than a helpless vapor . . . . all falls

aside but myself and it,

Books, art, religion, time . . the visible and solid earth . . the atmosphere and the

fringed clouds . . what was expected of heaven or feared of hell are now

consumed,

Mad filaments, ungovernable shoots play out of it . . the response likewise

ungovernable,

Hair, bosom, hips, bend of legs, negligent falling hands — all diffused . . . . mine

too diffused,

Ebb stung by the flow, and flow stung by the ebb . . . . loveflesh swelling and

deliciously aching,

Limitless limpid jets of love hot and enormous . . . . quivering jelly of

love . . . white-blow and delirious juice,

Bridegroom-night of love working surely and softly into the prostrate dawn,

Undulating into the willing and yielding day,

Lost in the cleave of the clasping and sweetfleshed day. (79)

This erotic passage (which Whitman revises and which appears in section 5 of “I Sing the Body Electric” in later editions of Leaves of Grass) not only has four-dot ellipses, but there are two-dot and three-dot ellipses, as well. In the next four editions of Leaves of Grass, the ellipses in this poem are replaced with commas, except for the first one (“vapor . . . . all falls”), where the ellipsis becomes an em dash, and in some editions, “ebb . . . . loveflesh” becomes “ebb – loveflesh.” By the 1881-82 and Deathbed edition, all ellipses and em dashes in this poem become commas. Thus, the comma signifies the separation of a list of items modifying “it,” which is the “female form.” In that capacity, these ellipsis markings behave similar to the ellipsis markings in the “Talbot Wilson” notebook.

However, the markings in the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass vary in length from two dots to four dots. The first two-dot ellipsis appears on page 61, or about two-thirds of the way through Leaves of Grass, and from then on the two-dot ellipsis markings appear frequently. So the marking is not an aberration. What may be happening, however, is that these markings — since they behave like commas, which not only indicate a separation of list items, but also indicate a pause in reading — indicate places to pause in breath longer than a comma would indicate. The more the dots, the longer the pause. The dots behave much like the white space behaves in a line of a Charles Olson poem. In an Olson poem, the longer the space, the longer the pause. The pause is part of the breathing apparatus in Olson’s “Projective Verse,” which is Olson’s essay about a poetics that uses and marks breathing in a poem. In “Projective Verse,” Olson writes:

the HEAD, by way of the EAR, to the SYLLABLE

the HEART, by way of the BREATH, to the LINE (55)

Olson suggests a relationship and maybe even a dependence between the line and the breath. Miller also suggests something similar in his “‘open air’ poetics” (100), when he too quotes Olson, “any poet who departs from closed form . . . ventures into FIELD COMPOSITION — puts himself in the open” (100). While Miller focuses on the larger issue of free verse, I focus on the discrete parts or markings of that free verse for Whitman. Nonetheless, it appears Whitman anticipates Olson’s Projective Verse by 95 years.

One could assume, that Whitman either changed his mind on the longer pauses, or he felt the longer pause would exhale itself naturally with just the comma notation he uses in later editions of Leaves of Grass. Or maybe it was also a revision mark, since each version of the above quoted passage changes a little bit in each successive revision in later editions of Leaves of Grass. Also important is how Whitman varies or enhances his use of elliptical markings from versions to version. With that in mind, I return to the “Talbot Wilson” markings.

Visionary Markings in the “Talbot Wilson” Notebook

Earlier, I showed how em dashes and ellipses appear to work within the notebook, but because I’ve shown that other uses of the markings are often different than the notebook’s uses, I can begin to illustrate how Whitman (and not the text in the notebook) may have used the markings. To do that, I want to look at the passages on pages 28 and 29 that I looked at earlier, and then show that by the time of the Deathbed edition, the lines with em dashes have not only been revised in “We Two, How Long We Were Fool’d,” but they were also expanded, and this expansion came by way of modifying or qualifying. It came by way of thinking longer.

The em dashes and the ellipses in the “Talbot Wilson” notebook are forward moving and future looking. They move forward as the thrust of the marking pushes or directs the reader to advance. They are future looking because as Wilhite says, “Whitman’s linguistic theory adopts an evolutionary momentum toward the future, but this momentum depends upon the recapitulation and revision of what has gone before it” (Wilhite 924), and what goes on before is the notebook. The before, for example, is the poem I looked at earlier:

The soul or spirit

transmutes itself into all

matter — [. . .]

(Talbot 28, Folsom’s transcription)

By the final revision in “We Two, How Long We Were Fool’d,” it expands to:

Now transmuted, we swiftly escape as Nature escapes,

We are Nature, long have we been absent, but now we return,

We become

(Leaves 1891-92, 93)

Notice that the em dash is not in the revision. The em dash is revised and expanded into the new, additional content, or words. Further, not only does the content expand from 14 syllables to 32 syllables, but the single “soul” or “spirit” expands into “we,” where “we” is Whitman and the reader. Whitman, as a result, has also modified and expanded “soul.” His thought becomes more inclusive — it’s not just one soul, it is two people. And this is only what happens before the em dash; even more qualifying occurs later. In fact, lines 5-11 of the notebook become the long lines of 4-8 and 10-11 in the revised poem. The lines grow as more fish, animals, fish, and environments are included as part of what “We become.” In addition, Whitman more clearly qualifies what is transformed. For example, on page 29 of the notebook, the lines:

he must

be orbic and balanced

in the air like this

earth

(4-9, Folsom’s transcription)

are brief at 14 syllables and brief in description as compared to the last half of line 12, “we it is who balance ourselves orbic and stellar, we are as two comets.” Not only are there more syllables and the description more detailed, but Whitman again expands on the subject. “He” becomes “we.” Whitman’s willingness to be more inclusive means he needs to expand his thoughts and lines. Further, the anaphoric sound unit is prolonged. Meaning, on page 28 of the notebook, “into” is the anaphoric sound unit that is only repeated four times, and on page 29, “he must” is only repeated three times, and “he would” is only repeated three times. In the final version of “We Two, How Long We Were Fool’d,” the anaphoric sound unit is revised to “We” (and often with “We are”), and the “We” is repeated at the beginning of 18 lines. The anaphora creates a long rhythm, and a long rhythm of anticipation and inclusiveness. As the reader reads the poem, they expect to hear “We” on the line turn, and they are rewarded when they hear it, and this reward creates an even stronger bond with the poet – an inclusive bond.

While there aren’t many uses of the ellipsis markings compared to the em dash markings in the “Talbot Wilson” notebook, and subsequently later revisions of the lines, the passage on page 113 can be examined:

Justice ,

does not defineis not varied as

upontempered the in passage of [illegible. struck through.]

laws by legislatures . —The

legistlatures cannotsettlealter

it any more than they can

settle love or the attraction of gravity or pride. —

The quality of justice

is in the soul. — It is

immutable . . . . it remains

through all times and

nations and administrations[??]

. . . . it does not depend

on majoritiesandand

minorities . . . . Whoever

violates it [illegible]shall

full pays the penalty

just as certainly as he

who violates the attraction

(My transcription)

On the last page of the 1885 edition of Leaves of Grass, these lines become:

Great is Justice;

Justice is not settled by legislators and laws . . . . it is in the soul,

It cannot be varied by statutes any more than love or pride or the attraction of

gravity can,

It is immutable . . it does not depend on majorities . . . . majorities or what not

come at last before the same passionless and exact tribunal. (95)

Some of the notebook lines are rearranged, and the lines “it remains / through all times and / nations and administrations[??]” are relocated further down the poem. What is obvious, though, is that Whitman once again expanded on what he meant by “majorities.” As a result, the line expands. Further, it is easier to hear the projective verse markings in the 1885 edition with “majorities . . . . majorities.” One needs an extended pause between the two occurrences of “majorities,” since it would be too difficult to repeat the same word without a longer pause. It is as if Whitman stops for a moment before qualifying and expanding his thoughts. These lines appear in following editions, until the 1881 edition and 1891-92 editions, when they are removed. In the editions where the lines appear, the ellipsis markings become em dashes.

Notable here, and in the previous examples, is how Whitman not only lengthened the line, but how the line became representative of a thought &emdash; a long thought. If the pages in the “Talbot Wilson” were wider, he might have written, “it does not depend on majorities and minorities . . . .” as one line instead of three. Still, there is the ellipsis marking indicating that he needs to expand his thought at some future time. His thought becomes the line. As his thought expands, so does his line. But first he needed to know what that thought was, and since he didn’t know it at the time of inscribing the notebook, he left markings to tell himself to develop this thought. It’s as if “Whitman found his line before he found his voice” (Miller 22) or found his fully developed thought. In the end, Whitman had multiple uses for the ellipsis and em dash marking, but the first use in the “Talbot Wilson” notebook marked expansion. It marked a note to the future.

Notes

1 Places where the em dash marks the end of a poem occur on pages 21, 31, 33, 42, 46, 65, and 111, and they might also occur on pages 26 and 108. I will use page numbers as they correspond to the scanned page numbers on Notebook LC #80 at the Library of Congress website, as opposed to the page numbers in Notebooks and Unpublished Prose Manuscripts edited by Edward F. Grier.

2 In the 1867 edition of Leaves of Grass, three-dot ellipses appear in “Year of the Meteors” (51a), in “When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom’d” on pages 3b and 12b (this poem also has six-dot ellipsis on pages 4b and 8b), in “Chanting the Square Deific” on page 15b, in “I Heard You, Solemn-Sweet Pipes of the Organ” on page 17b, in “O Me! O Life” on page 18b, in “As I Lay with My Head in Your Lap, Camerado” on page 19b, in “This Day, O Soul” on page 19b, in “How Solemn, as One by One” on page 22b, in “Reconciliation” on page 23b, in “To the Leavened Soil” on page 24b, in in section 21 of “As I Sat Alone by Blue Ontario’s Shore” on page 20c, and in “As Nearing Departure” on page 27c. And a four-dot ellipsis appears in “The Dresser” on page 31a.

In the 1872 edition of Leaves of Grass, a three-dot ellipsis appears in “I Heard You, Solemn-sweet Pipes of the Organ” on page 119, again in “As I Lay with My Head in Your Lap, Camerado” on page 190, again in “The Year of Meteors” on page 242, again in “Reconciliation” on page 295, again in “How Solemn, as One by One” on page 297, in “To the Leavened Soil” on page 298, again in “O Me!, O Life!” on page 361, and in as “Time Draws Nigh” on page 373. Also, a four-dot ellipsis in “The Dresser” (again) on page 285, in “To Oratists” on page 347, and in “Banner and Pennant” on page 352. There is also a nine-dot ellipsis in section 21 of “As I Sat Alone by Blue Ontario’s Shore” on page 326 (which was previously a six-dot ellipsis”).

Works Cited

Higgins, Andrew. Art and Argument: The Rise of Walt Whitman’s Rhetorical Poetics, 1838-1855. University of Massachusetts Amherst, Ann Arbor, 1999. ProQuest, lynx.lib.usm.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/304514974?accountid=13946.

—. “Wage Slavery and the Composition of Leaves of Grass: The ‘Talbot Wilson’ Notebook.” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review, 20 (Fall 2002): 53-77, doi.org.10.13008/2153-3695.1701.

Miller, Matt. Collage of Myself: Walt Whitman and the Making of Leaves of Grass. University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

Olson, Charles. “Projective Verse.” Human Universe and Other Essays. Edited by Donald Allen. Grove Press, 1967, pp. 51-61.

Wilhite, Keith. “His Mind Was Full of Absences: Whitman at the Scene of Writing.” ELH vol. 71 no. 4 (2004), pp. 921-948. Project Muse, doi.org/10.1353/elh.2004.0052.

Whitman, Walt. “I am the poet of slaves.” Transcription by Ed Folsom. Walt Whitman’s Drafts of “Song of Myself”: Leaves of Grass, 1855,” bailiwick.lib.uiowa.edu/whitman/specres04.htm.

—. Leaves of Grass. Brooklyn: 1855. The Walt Whitman Archive, edited by Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1855/whole.html.

—. Leaves of Grass. Brooklyn: 1856. The Walt Whitman Archive, edited by Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1856/whole.html.

—. Leaves of Grass. Boston: Thayer and Elrdige, 1860-61. The Walt Whitman Archive, edited by Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1860/whole.html.

—. Leaves of Grass. New York: 1867. The Walt Whitman Archive, edited by Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1867/whole.html.

—. Leaves of Grass. Washington, D.C.: 1871. The Walt Whitman Archive, edited by Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1871/whole.html.

—. Leaves of Grass. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1881-82. The Walt Whitman Archive, edited by Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1881/whole.html.

—. Leaves of Grass. Philadelphia: David McKay, Publisher, 1891-92. The Walt Whitman Archive, edited by Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1891/whole.html.

—. “Mercury – he must be.” Transcription Ed Folsom. Walt Whitman’s Drafts of “Song of Myself”: Leaves of Grass, 1855,” bailiwick.lib.uiowa.edu/whitman/specres02c.html.

—. “Notebook LC #80” [“Talbot Wilson” notebook]. Library of Congress, loc.gov/item/wwhit000002.

—. “The soul or spirit.” Transcription Ed Folsom. Walt Whitman’s Drafts of “Song of Myself”: Leaves of Grass, 1855,” bailiwick.lib.uiowa.edu/whitman/specres02b.html.

Leave a Reply