Someone has razed the house and hung its walls vandalized by a tormented resident. Standing back affronted, but scrutinizing the display nevertheless, twelve panels come into view as if roof, hallways, furniture, and floors of this dwelling has been shunted. These are walls, scrawled upon and dirtied by a frenzied hand. These are projections, gargantuan biographical Rorschach blots, of a mind swarming with bees. To the dwarfed witness scanning this art installation, it appears a suspended miasma, partly due to it immensity, but also because of violent and chaotic streaks, smudges and smears of strange tonality. One wonders if the gallery roof has leaked or crazed activists have broken in to defile the canvases with water and lye. Splotches of red and black cankers arise to adjusted sight as if open wounds from the predominately bone color of the panels. Closer, paint drains like horror movie blood streaking over stark crimson and tangerine flash splattered stars; light Aegean blue dimmed with an underpainting of skim milk white obfuscates like smoke; riddling canvas after canvas dark lines, borne perhaps from a graffiti artist’s bold black Sharpie, conjure an armada in an odd, orderly formation being savaged. Given all this, still the human eye here is a weakened instrument.

Drawing near, fearing as much the clichéd moth’s demise, and examining the first of the twelve panels, there along the upper right-hand corner, lays a sliver of Kelly green, nothing more than a stroke of paint. This is a stamp perhaps from the resident of this dismantled house. This green streak, blooming as it does amid the immensity’s chaos, seems careful and full of intention. It says it was madness in here, but there was still presence of mind, that in all the hues of brutality, hope remains that something anew flowers from catastrophe. The particular color never reappears. As one works their way through Lepanto, the chosen palette takes on an organizational pattern arranged in two-three-three sequences throughout the twelve parts. Each panel represents a particular, shall we say, camera angle: bird’s eye, mid-shot, panoramic. While these angles are repetitive, here color is king. It is the repetition of color that gives Lepanto voice. Sometimes surd, sometimes susurrant this voice all the while canting: history repeats itself. As one becomes more accustomed to the work, like slowly regaining eyesight in bright sun, Cy Twombly’s Lepanto impacts like a grotesque triune, consisting of three panels in each section, segued by three bird’s eye view panels. In each section the story is repeated by way of signifying colors. In this way, Lepanto is a twelve-part loop of Acrylic, wax crayon and graphite grouped in three repetitive chapters. If folded back in on itself, the resulting structure would be a mausoleum to war. In these times of discordant moral rectitude, some might then secure materials to reattach a roof, establish hallways, bearing beams and install a suitable door to be sealed forever pleading ignorance to the drone from within its walls. The installation does depict horror, this is true. It does so addressing our fragmentary and vapid attention span, borrowing conventions—the shaky camera Dogma 85 edit—from movie houses, home to our most passive form of numbing inoculation. But for that green, that wondrous green daub of hope. It’s telling us something, if we focus, if we slow. To ignore this detail, to mock it or blink to dismiss it is to assist the sextons burrowing our own burial plots. We can’t walk past without pause.

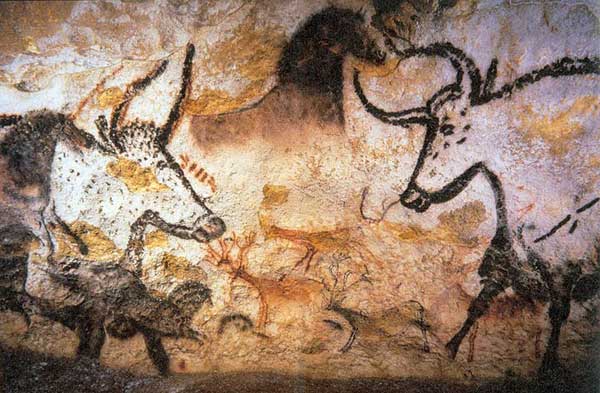

First and foremost, Lepanto is the story of a 16th century naval battle between Turkish imperialists and Christian isolationists, delineating in history the Ottoman Empire’s demise. The alliance of Papal States, coupled by Spanish and Venetian might, helped to vanquish the Turks. Eyewitness accounts of the October 1571 battle said the waters turned red with blood; that smoke obscured the sun; ships burned gold and crimson against the night sky. The installation reads like a film reel—all that’s missing are those upper right-hand burn marks on film, called “the real,” which tells the projectionist when to switch reels. The work appears rudimentary and haphazard, perhaps even stained or damaged from afar, but closer examination shows the genius of composition in recreating the conflagrations of combat at sea. In one respect, the vessels and oars Twombly creates harkens back, pays homage to, the Lascaux cave paintings. Those Paleolithic paintings, found in 1940 by a group of young boys and their scampering dog in southern France, were drawn on the walls of underground caves and were characteristically large and crude.

Moving forward through time, the Lepanto painter takes on another watershed of art. The painting drippings, and blobs, found in most of the panels might find progeny in the likes of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, although Twombly’s hand appears less taut, more childlike. The impasto, where brush strokes are visible, suggests Twombly’s signature of departure from those 1940-50’s abstract expressionists, whose strokes were more aerial in orchestration than grounded upon surface. In another respect, the recent past is evoked here too. Jean-Michel Basquiat, New York’s art wunderkind who died in the 1980s, could have easily scrawled Twombly’s boats on the walls of lofts in the Meat Packing District. In a way the artist uses the history of his medium, pulling the viewer from 15,000 BC through to modern times, in order to illustrate while an idiom changes, of what it speaks of does not. An age sharpens or dulls a work of art by its implications. Whatever is derived in service of his goal, the impact is original and revelatory. Lepanto , like Homer’s Iliad, speaks of a point of history, but also voices contemporary concerns. Both are implicated by what the viewer brings to the work of art. Art instructs outside of time. A viewer’s experience serves to re-create the initial impetus, the creative response to an external stimulus. Since this is a nation at war to say Lepanto is a direct dialogue with the U.S. citizenry is not overstating the case. Therefore, those mad bees might just be inside us all. This bedraggled house might be our very own. Those burning ships our flotilla far from these shores.

But of course, not everyone can live with this, to live within those walls or even cultivate an understanding of such a structure. Abstractions tend to speak highly individualized lingua franca. What one hears might not be what the other hears—or sees. The soldier will invariably be drawn to Twombly’s panels of destruction as if in the inertia of duty. The engineer might be inquisitively drawn to the vessel formation and calculate the number of oarsmen to gauge propulsion. Those seeking the substance of things hope for might be drawn to open spaces or skeins of green. “The way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe,” writes John Berger in his seminal work of art viewing, Ways of Seeing. In this light, Lepanto can be approached in two ways—seeing is believing or believing is seeing. Abstract art is more about the viewer than what is being viewed. This meaning, this projection finds its source in personal psychology, undoubtedly, but also surely within the psychosis of a society.

First coined by Jungian Marie-Louise von Franz in her 1978 volume, Projection and Re-Collection in Jungian Psychology, “projection” is the process by which a mind, faced with perceptions about itself that it finds unapproachable firsthand, buries these perceptions in the unconscious. The unconscious, then, being indisposed to such reticence, finds some other way of dealing with the material. Slyly it then projects this repressed perception onto some external person, thing, country; it could be a wall in a cave, a wall in a suburban home, foreign power, a canvas to be hung in a gallery, the words found in an essay. By externalizing the mind can then address the material in a disguised form of objectivity, resulting in either some overt form of action; this might manifest itself in homophobia, racism or warmongering.

Fittingly, Lepanto, composed in 2001, came in an era of heightened fear, a time of terrorists and extraordinary carnage. In Twombly’s retelling of this historical battle, empires puff up their chests and pay for their hubris; witnesses say the sea turned to blood; the point of view changes, but the story remains the same. Nothing remains that violence cannot put asunder until it defiantly grows to battle anew. Violence is always responded to with violence. When terror hit American soil, force was dispatched to its supposed source. But fat with vengeance and a penchant for half-truths, the U.S. government continued its push to ferret out those who would do her harm. With zealotry, it proffered black or white stories about the gray world. The administration drew its sword on false charges and continues to this day to torment its denizens with packaged rationale, which rains like so many veils. It is an administration the Ottomans would have been proud of, an administration after its own deceitful heart. The cycle never ends. Death is supremely victorious. Truth is its first victim upon which the darkness curtain falls.

It is perhaps important for a viewer to concentrate on the installation, in particular paying close attention to panel number six. This panel, this wall of the house dismantled, is cleaved. There is a duality here, at the very least, a sense of “before,” and “after,” – a demarcation of sorts. Moving left to right a third of the canvas is distant and foggy until like a sudden storm cloud the right portion of this scene intrudes. Dark blood and sores are exposed; yellow flourishes and blackness reigns in a shroud of paint. Viewers might be drawn here, swaying side to side imperceptively, trying to come to grips with this marked implication. There is a time before, just before the veil comes down, and then it’s through the dripping darkness we go, until as Lepanto shows, we circle back and find ourselves once again on the doorstep of this strange house. If only we stopped to contemplate “the real” green. But it’s just a painting, albeit a large one, composed by an addled old man who doesn’t even live here.

Lepanto then becomes an ironic entity of an age, an age the CIA could describe as a “wilderness of mirrors.” This is the term used for when operatives lie and their lies are piled upon lies making the truth all but inaccessible for its wild thicket lair. Everywhere we turn reflection upon reflection produces discombobulation and nausea. Here truth no longer matters. Here, what you see is what you get: Yourself staring back. Oh, then it all must be okay. I trust that person. Of course, who supplies and polishes these reflections, we do; we, the people unwilling to speak of what some see in the horrid canvases hung for us nightly and broadcast. To say the house first must be dismantled, put on display for others to see. There must be blood and explosions; there must be uncertainty and carnage. There must be a chronicle of torment, a drone in the skull. Still, it’s open to interpretation, but at least what is viewed, ugly and scary, will be more than our own façade. It is a viewing inside that Huber hive of the soul, where masks are removed. The personal unmasking that Lepanto guides, answers these queries with devils, disturbances and, for some, deliverance. It depends if one notices Twombly’s deus ex machina, that sliver of green.

chad henry says

Interesting take on Twombly.