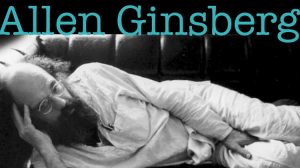

My friend Sylvain went to San Francisco recently and brought us back some souvenirs as gifts. One of the places he’d visited on his trip had been City Lights Books. He brought me a t-shirt from there. And he also brought me one of the most complicated objects I’ve ever had in my possession: a khaki-colored baseball cap emblazoned with the word HOWL in large, black capital letters. The word, and the font it was printed in, referred to the landmark 1956 poem “Howl” by Allen Ginsberg, which, in addition to being widely considered one of the signal flares of the Beat Generation, was also hugely influential for me personally. My first reaction was to think of how much I loved the poem, and how thoughtful the gift had been.

I put the hat on, glanced at myself smiling in the mirror, and then quickly took it off again. For some reason, I felt a little queasy. As I looked down at the hat in my hands, it morphed into some kind of philosophical Rubik’s cube. I found myself mired in thickets of unnavigable implication. Of course I wanted to be out there, reminding people of Allen’s work, spreading the message that his poetry was still relevant. But wasn’t there some automatic conflict of interests between the Beat Generation’s tireless excoriation of middle-class American consumer values and the subsequent commodification of their image as a product? I decided to sit down for a little while.

I thought of how disgusted I was when I first saw the ad campaign in which the Gap was posthumously using Jack Kerouac’s image to sell their pants. “Kerouac wore khakis,” read the tag line, printed across a picture of Jack from back in the 50s. At the time, my friend Bill Harper, another great poet who helped to light my path, came up with the brilliant idea of xeroxing pictures of Hitler with the SS and adorning them with the line “Hitler wore Khakis” before slotting them between all the pairs of jeans in the nearest Gap store in protest. That’ll teach em.

But this case was a little bit different. Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the proprietor of City Lights Books, where this hat had been acquired, was also the guy who published the poem to begin with. So it’s not like he was distributing these hats without the necessary consent. It is true that Allen is dead, so we can’t be absolutely sure about what he would say. But when I assisted in the summer-long tribute to Allen at Naropa University back in ’94, I personally watched him autographing t-shirts with his own face screen-printed across the front. So it’s safe to say he wasn’t altogether unfamiliar with the concept of apparel marketing. And Ferlinghetti, who callously grabbed my ass and made a lewd remark when I asked if I could show him some of my poetry that summer, has never seemed to me to be particularly above cynicism. So it’s not clear that anyone has been sold out against their will here.

Besides, these guys do sell books, after all. And Allen even helped to found a school (in Kerouac’s name) where tuition is charged. So it’s not like he was ever really allergic to making a few bucks off of himself or the Beat thing. But then, when I wear the hat, what is it that I’m advertising? Is it Ginsberg or Ferlinghetti, or their personal values? Or is it the content the poem? Or by advertising the content of the poem, am I really just advertising City Lights Books, who hold the publishing rights? Then again, in turn, am I advertising for the Ginsberg estate, who must still receive royalties from that? And who gets that share of the royalties now that Allen is gone? Then I started to wonder if the sale of the hat product had been timed to coincide with the recent release of the 2010 film Howl, which dramatized the obscenity trial brought on by the publication of the poem. And in that case, would wearing the hat now also be advertising the film? And was the hat a licensed product of the publishing house or of the film studio? Could a share of the profits from the hat product be going back to the production budget of the movie? Into the pants of some Hollywood producer, or James Franco’s agent?

Besides, these guys do sell books, after all. And Allen even helped to found a school (in Kerouac’s name) where tuition is charged. So it’s not like he was ever really allergic to making a few bucks off of himself or the Beat thing. But then, when I wear the hat, what is it that I’m advertising? Is it Ginsberg or Ferlinghetti, or their personal values? Or is it the content the poem? Or by advertising the content of the poem, am I really just advertising City Lights Books, who hold the publishing rights? Then again, in turn, am I advertising for the Ginsberg estate, who must still receive royalties from that? And who gets that share of the royalties now that Allen is gone? Then I started to wonder if the sale of the hat product had been timed to coincide with the recent release of the 2010 film Howl, which dramatized the obscenity trial brought on by the publication of the poem. And in that case, would wearing the hat now also be advertising the film? And was the hat a licensed product of the publishing house or of the film studio? Could a share of the profits from the hat product be going back to the production budget of the movie? Into the pants of some Hollywood producer, or James Franco’s agent?

Then I thought, well, at least I didn’t pay for it myself. It’s something I got for free, without having to work for it. I mean, for all I know, Sylvain didn’t pay for it either. It might have been a handout at a function he attended. Maybe I’m not economically supporting anything at all. Not directly, anyway. And the hat does advertise sincere values of mine by promoting a poem that I truly think is good, important work. And even if the film about the poem isn’t quite the singular piece of century-changing genius that its subject matter is, it’s still probably something worth seeing in its own right. Especially since it serves as an introduction to Allen’s work for a whole new generation. And we need to be building new vehicles to transport our sacred artifacts into the future. I’d love to think that my hat might cause some young person to go check out a movie about Allen and get pissed off about the persecution of poets by the McCarthy-era American courts.

But then I got worried again. If the Beats were about fighting the status quo and rejecting mainstream consumer values, hitting the road to find their own experience of the American dream without the pre-packaged morality and stability that the culture was offering them, then putting that message on a hat and selling it (or buying it for that matter) suddenly becomes tongue-in-cheek. Ironic. And there’s nothing the next generation seems to have a firmer grip on than their sense of irony. The kids in the street have no way of knowing I didn’t pay for the hat. So if I’m walking around wearing it in order to literally promote the message in the poem that it references, have I already failed? Am I so sure to be taken ironically that I’m actually making fun of the poem by wearing the hat? Could I even deter some cool young people from thinking they should see this movie or read this poem because I look like such an impossibly uncool middle-aged dimwit in this hat? If I really want kids to read the poem, should I just get a marker and write the word howl on a white t-shirt? Or is that kind of DIY punk stuff already old and ironic as well?

Anyway, even if Sylvain didn’t pay for the hat, someone who sees it on me and likes it might be tempted to buy one for themselves. And even if all the money made by this product was going somewhere decent, like, say, to City Lights’ ongoing effort to discover and publish new and exciting young poets (after grabbing their asses), wouldn’t I still just essentially be advertising the purchase of products as an expression of one’s values? And how Beat is that? I mean, whether it’s baseball hats, movie tickets, or even books, if you’re saving up your money, or preserving your good credit, so you can buy these objects as banners of your value system, then you’re probably not off thumbing your way around the back roads of the country, smoking grass with jazz musicians and exploring your sexuality while spewing your cosmic soul vomit onto the pages of your tattered notebook.

This was a whole new wrinkle in the problem. If the hat was made in a communist country, then does that support or exploit communism? On the one hand, it seems like any money sent to China must on some level help the Chinese. But what if the Chinese worker is being exploited? Or what if the communist countries are being exploited by the capitalist ones? Or if they’re exploiting their own citizens in an ironic act of de facto capitalism? And how much of the money spent on the production of the hat actually goes to China anyway? Does most of that money go to China? Or does most of it stay here and a small amount go to China? Now, of course, I’m in way over my head because I don’t really have any idea how international manufacturing deals are financed between nations that operate in ideologically opposed economic systems. So whether the percentage of money going to China was high or low, I wouldn’t even fully understand the ramifications of that. But it would be nice to feel like I at least understand what it says on my hat.

If we purchase and wear goods produced in communist countries, is that a symbolic endorsement of communism? Like the opposite of when people say “Buy American”? Or is it simply an exploitation of the cost/resale value ratio that is only possible because the US has a higher per-capita income than China does, meaning that we can pay less money to a Chinese person to make things for us than we would want to be paid to make the same things for ourselves? And if you’re a communist, does that bother you? Or are you primarily concerned with having the same as your countrymen regardless of what is had by those of other countries? Does communism depend on global economic quality, or is it satisfied with mere national economic equality? I honestly don’t know the answer to that.

And if we’re buying all these hats from China and China’s getting rich, then why do they still have so many hat-factory employees? Is it because we’re underpaying for the merchandise, compared to an objective market value? Or is it just because their population is so high? And is that hurting them economically? Or is it helping them? Is their population growth actually a sign that they are thriving? And if that’s the case, then has the Howl hat fallen back into literal lockstep with the sympathies expressed in Allen’s poetry? Am I helping a communist nation to thrive by sending them another hat-making job that my own people are too lazy and entitled to want? And does that mean that the hat functions as a physical indictment of the same empty consumer culture that the Beats originally aimed to question? What would the Beats think of all this? Would they even concern themselves with it? Would they wear a hat at all? Would they take sides in the discourse about China? I know that they were quite fond of incorporating Eastern philosophy into their world view. Allen himself was a devout buddhist. But would Allen bother with such explicit politics in his work? And would his work even make sense in another country? Or is he himself just a purely American product? A wail that could only have emitted from the tortured guts of the postwar American dream?

On the flip side of the Made in China tag, it says: Designed in America. So maybe the majority of the money that’s paid for the hat is staying in the States, where the ‘intellectual property’ of it was born. But then, who is that money empowering in the US? Maybe the producers of the hat had to pay some small amount to the estate (or even back to themselves) to license the word and its corresponding font for the logo. But after that, where do the profits go? How high does that food chain climb? Who gets the final dollar? Is it just some random corporate glutton who doesn’t even know that one of his business ventures has shamelessly sold out the anti-consumer element of the Beat Generation aesthetic? And who’s sniffing Ferlinghetti’s pockets? How many people are grabbing his ass? Printers, distributors, advertisers. What kind of cut is Amazon taking from the online sales? How high are the rents in San Francisco these days? Are any of the people who profit from this product even aware of their own irony? And if I think of all this stuff before I put the hat on in the morning, then when I wear it am I being ironic regardless of my intentions? Is it clear to other people that I’ve factored all these questions into my decision to wear the hat? Or might I come off like I haven’t even thought about it? Like I’m just some tourist who wandered through a literary movement on my summer vacation?

I think of another poem in the book, “A Supermarket in California,” in which Ginsberg tries to commune with the spirit of Walt Whitman while roaming the neon-splashed aisles of the titular American grocery store. And I wonder if that’s what I’m somehow trying to do with my hat. Trying to find the holy spirit of poetry among the objects being purveyed in the shiny apocalyptic marketplace of occidental excess. But the person who sees me walking down the street in this hat can’t possibly know that’s what I’m trying to do. I don’t even have any way of knowing who’s going to see me in the hat. And I imagine that what I’m advertising by wearing it will change completely depending on who I’m advertising to. So what if the people who see me wearing the hat don’t take the time to think through all the issues that carefully? What if they just look at the surface? And what if the surface looks different to each person who sees me? Does it even matter whether or not I work out how I feel about all this stuff? I might just wake up tomorrow and feel differently about the whole thing, anyway. And I guess that just leaves me right back where I started: I put the hat on, I take the hat off, I put the hat on, I take the hat off…

Leave a Reply