Contemporary writing demands originality from the artists, and it requires they develop their creativity employing other means and materials in their works. With the written works, it is quite similar. Writers are asked to show how good they are making new creations in which innovation uses to be the protagonist. However, more often than not, originality also requires breaking the rules, both at a syntactic and a semantic level. Moreover, writers are confronted with a great dilemma: how to express themselves, how to be creative but not being rejected because of being too much opaque or confusing to be understood? Susan Howe provides a perfect example of this dilemma in her poetry. Being one of the most innovative and experimental poets of our century, she combines experimentation and tradition in such a way she does not remain indifferent for any reader. I’ll make a brief analysis of her work, paying attention to particular aspects where she shows how the contemporary writer confronts this dilemma.

For that purpose, I will analyze her work from two perspectives: the formal and the semantic one. From a formal point of view, I will discuss her concept of the poetic work as a piece of art not only compose of words but capable of including any other element the poet chooses such as photographs, drawings, tissue papers, etc. I will refer to the different formats she employs for her books and the way she transforms most of them in artistic works to be read and contemplated. From a semantic point of view, I will discuss on the importance readability has in her work and how its disruption does not prevent the reader from interpreting her works. I will also mention some useful techniques contemporary readers use to employ to approach such type of works.

For centuries the poetic work has had to fulfill specific parameters (aesthetic, acoustic, formal, or content) to be considered as such (Wolosky 2001: 16-21; Puktas 2006:1-4; Strachan and Terry 2011: 23-46). From all these parameters, the aesthetic one was usually recognized as one of the most important. Poetry was expected to provoke an emotional reaction on the reader, either positive or negative. The poem could make the reader laugh or even cry, but the lack of emotions was not assumed as a possibility (Hanaver and Rivers 2004: 9-11). Besides, the poem was also expected to keep a rigid formal structure that was not allowed to be abandoned, either.

With the arrival of Modernism, and later on, Avant-Garde movements, a revolution would take place in the literary scene (Jenkins 2008: 2-6; Finch 2002: 400-411). All these movements would bring new perceptions of the poetic work, which would include the use of elements such as the “free verse,” the “found objects,” or the exploration of the visual dimension of the printed page, among others. From that moment onwards, the poetic sphere would contemplate two main poetic currents.

There is a limited one, represented by poets like Gerald Stern, Wanda Coleman, Ted Berrigan, or Karen Volkman. These poets represent that group of artists who will enjoy using traditional metrical patterns while working with current themes; this is a current particularly important during the ’80s and ’90s (Dacey and Jaus 1986).

A second current, this one much more numerous and heterogeneous, is constituted by those poets who consider the poem is a work of art in which to express their creativity without limits imposed by syntax, space, or content. Though it is difficult to trace specific literary movements within this group, they can be grouped by taking into account certain common aspects.

So, for example, there is a significant group whose interest goes around a particular use of the written language. For them, it is no longer a medium of expression but an object they work with in order to approach a reality they consider chaotic. Within this group, I could mention poets like Charles Bernstein, Lyn Hejinian, Bruce Andrews, Bob Perelman, or Susan Howe,1 whose works I will use to exemplify some aspects of my analysis in this article.

Other poets use their work to make a defense of the feminine figure. Furthermore, some will use their work to claim their ethnicity. Although each of them possesses a very personal style, all of them share something in common: they are part of a generation of artists who conceive poetry as something alive, as a creation which is in continuous change and cannot be limited to a specific set of metrical patterns or a solid thematic line.

The interest of this article is going to be centered on the second current. The schism between form and content gives way to two essential questions: How can the reader interpret this type of poetry when all their referents and key aspects disappear?2 Also, does the poet have to sacrifice content in favor of expanding their creativity?

I will try to provide an answer to these two questions through this article in a practical way. I will use examples from contemporary poets3 that would help me to illustrate relevant aspects concerning the role of the reader or the possible ways that they have to approach this type of poetry where there is such a disruption between form and content. I will start discussing the traditional concept of poetry as an object to provide aesthetic pleasure to the reader and how it has changed in our times. Then, I will discuss the new role adopted by contemporary readers that have passed from “receivers” to “builders” of the message. Finally, I’ll center my attention on the poetic work, and will provide some possible techniques the reader could employ in order to get accessibility to poems that seem to be opaque.

Nature of the poetic work

If we were to determine what purpose poetry pursues, we could enumerate many elements attending both to its formal and content aspects. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary, in one of its meanings, provides a useful approach to what we would be initially considering poetry. This dictionary says it consists of a “writing that formulates a concentrated imaginative awareness of experience in language chosen and accepted to create a specific emotional response through meaning, sound, and rhythm.”

This definition contains two crucial characteristics we observe closely related to a traditional perception of poetry.4 On the one hand, poetry is expected to provoke an aesthetic response to the reader, usually, a pleasurable one, using rhythm, rhythmic patterns, the use of specific terms, etc. (Tompkins 1980: 92-99). On the other hand, the poem seems to be perceived as a dialogue between its creator and a reader who receives it. The latter uses to get a message hidden in the written words by decoding the text (D´Haen, Theo and Pieter Vermeulen 2006: 19-22; Rosenblatt 1978: 1-5).

However, over time, different literary movements, in their interest in innovation, project new visions of the poetic work that abandon this tradition. One of the main characteristics they bring into the poem is the total disruption between form and content. Take, for example, this poem by William Carlos Williams entitled “This Is Just to Say”.

I have eaten

the plums

that were in

the icebox

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast

Forgive me

they were delicious

so sweet

and so cold

Williams, as representative of the Modernist movement, provides a poem without superfluous elements. The most disruptive element this poem contains is just the disappearance of the punctuation. However, that is not a problem for the reader to follow a message composed by three sentences whose frontier is marked by the use of capital letters at the beginning of what would constitute the second sentence: “Forgive me,” juxtaposed to the third one: “they were delicious so sweet and so cold”. Content also attracts the reader´s attention because of its simplicity. According to traditional canons, this would not be an appropriate theme for poetry: a poetic voice that apologizes for eating a fruit someone kept on the fridge! Nevertheless, that is attractive to contemporaneity. Any topic is susceptible to be part of a poem.

Now compare Williams´ poem to this one from the poet Susan Howe.

Howe presents a poem that reminds us of the so-called “found poems” (Trawick 1990: 187-195). It is made, apparently, from several overlapped fragments of texts whose reading is almost impossible as there are just a few recognizable words. Furthermore, what is the reader expected to do? How can they interpret it with so little information? Williams, with his innovation, is still in the first stage of experimentation. Howe, on her part, represents this new concept of poetry we are referring to. All reader´s expectations disappear, and their comfort area is in danger. The reader can no longer take for granted the information in the text but they have to move beyond the written material. There is not “an interpretation,” but many possible “interpretations” of one single text and all are valid. Nevertheless, the problem the reader confronts is the meaning is no longer in the words the text contains but much more in their disposition on the page, their fragmentation, and some possible clues the author has left as a departing point (Travis 1998: 45-50).

Reader’s role

As a consequence of all these changes in the poetic work, the role of the reader has suffered a decisive turn. Traditionally, the relationship between reader and text was understood in terms taken from the Structuralist theory (Scholes 1974: 13-38; Berman 1988: 132-138). The author emitted a written message, and the reader was just the passive entity that received it and gave an interpretation that used to be superficial as the meaning was quite evident. However, with the birth of the reader-response theories, the reader started to acquire their importance in the literary work. They started to be conceived as builder of meaning, and, in some occasions, like a kind of modern detective who followed the possible clues the poet had left in order to be able to create a coherent message, one of the multitudes of interpretations a poem could have as there was no longer just a valid one.

Inspiring ourselves in those theories, we consider it is possible to establish three types of readers attending to the grade of involvement they have with the literary text. So, we could speak about:

– The “superficial” reader.

– The “deep” reader.

– The “rebellious” reader.

The first one, the “superficial” reader, would keep characteristics in common with the reader of traditional poetry. It is a figure that pays attention to the words written on the text and looks for a literal message. They just look for syntactic relationships which allow them to get some meaning.

The second one, the “deep” reader, on the contrary, is that reader who takes the written text as a point of departure to look for possible references, names, allusions to external elements, etc. that allow them to enrich and get meaning beyond the poem.

The third one, the “rebellious” reader, is a figure we find quite frequently in contemporary poetry. This is the reader who, confronted with syntactic or semantic disruptions, rejects the poem classifying it as chaotic or opaque. At most, it is the type of reader who could feel slightly impressed with its visual presentation but does not try to make any interpretation of it.

The following poem will serve us as a practical example of how these types of readers would approach an original text.

At first sight, the reader notices the poem is mainly constituted by two parts: a prose fragment divided into two segments, and a group of verses intersected between those segments. The “superficial” reader would center their attention immediately in the prose sections. They are easy to read. They are ordered and contain a clear message. It is obvious they make reference to some episodes related to Charles I´s death as there are references to Heaven and expressions like “Joy and Comfort” that contain essential religious connotations. This reader could also look at the lines and feel some interest in the visual aspect they provide to the poem as they seem to follow like a cascade, to a certain extent imitating the ax that cut the king´s head.

The “deep” reader would go a step further. Their interest would be occupied by two elements that stand out in this poem. In the first place, the necessity the author had to include the bibliographical reference from which she took part of her material as part of her poem; and, in the second place, the visual presentation of the poem. The reader would center their attention on the way poetry interrupts the prose sections. Apart from the possible visual play with the lines, there is a kind of hidden message in those words waiting for the reader. Several possible interpretations could appear that are not written in the text.

The poem could represent a picture of the scene. The prose sections could correspond to the action taking place at the scaffold. The protagonists of the action could keep a serene and austere behavior as it was expected from their social status. However, the lines that cut those sections could represent the chaos caused by the plebs. Those lines could resemble the violence, the screams, and the disorder contained in such a situation. The reader could even go beyond the written text to the extent of interpreting the blanks spaces contained in the middle of the poem to represent the silences, the secrets of this historical episode, the intrigues those characters did not speak out but could be contained in that book the author mentions at the beginning. In this sense, we agree with the ideas of Wolfgang Iser (1993: 33-39). This text is made of disruptions, blank spaces which are left for the reader to enter their meanings. There are multiple possibilities of interpretation, and the reader is invited to surf into history to make their own approach to a dark episode in the life of Charles I´s existence.

If we placed ourselves in the position of the “rebellious” reader, we would say this seemed to be an extraordinary text because we could not classify as prose or poetry. It is a single text that combines both elements, and that was not “usual” in poetry, so the “rebellious” reader would probably reject it for being such a strange object.

These are just three projections we have observed in our analysis of contemporary poetry. The same subject could manifest the three stages on their approach to a poem as they are a useful measure to calibrate the degree of interest and inclusion every reader could manifest for a specific poetic text.

We consider the following quote could be a summary of what we have tried to explain with these interpretations.

In this sense, “the reader does not interpret the poem but the poem interprets the reader.” The event of reading a work of literature will unfold differently for the same reader at different times of his or her life as the reader´s history and nature evolve. The reader event also varies based on a reader´s “perspective of interest (Rovira 2019: 93).

As this quote expresses, we can never wait for an idealized reader because every reader is accompanied by their history, knowledge, cultural level, events, remembrances, and memories, and brings them into the poem. So, two people reading the same poem are going to manifest different reactions and different readings determined by their own experiences, and no author can agglomerate them into a single poem.

The nature of the poem

The nature of the poem has also changed. From being a passive entity waiting for an interpretation, it has transformed into a living creature that interpellates the reader and asks them to interrelate with the written words. The poem has also changed its materiality through the centuries. Formerly, from being composed just to be declaimed, it passed to be considered a literary work of art to be written down and be read in the intimacy, like a novel, an essay, or any other written composition (Pfeilier 2003: 13-25; Furniss 2007: 34-37). On certain occasions, it becomes an artistic object to be read aloud accompanied by music,7 a poetic composition denominated “performance poetry” that is becoming quite popular nowadays (Finch 2002: 341-350; Novak 2011: 19-45). Others, the poem is provided with the characteristics of a visual artistic object and is exposed in a museum, like a picture. Below you can see some photographs which exemplify this. They belong to the exposition the poet Susan Howe made of her book Tom Tit Tot (2013) at Yale Union (Oregon).8

As a result of all these changes, the poem is no longer conceived merely as an object to produce aesthetic pleasure. On the contrary, in the last years, poetry is acquiring meaningful social and political engagements. Many poets wish to awake the reader´s consciousness provoking their reaction against certain events they wish to denounce through their works.

Specifically, we can mention three specific representative groups within contemporary poetry that reflect the general view. In the first place, it is particularly noticeable that the role feminism is acquiring and how many writers, of all genders, deal with different aspects of women´s lives in their works. In the second place, it is also essential the role many ethnic groups are gaining, too. Poetry is the platform they find to denounce their social conditions, the way they confront everyday life in the middle of a society that does not always respect human rights or the problems immigrants face in the fight for a better life. There is a third group of poets whose interest centers in language and its artificiality. They consider language´s inability to express human experiences to be a reflection of the isolation and alienation the human beings suffer, so they emphasize the use of the linguistic code with the break of all possible rules to produce texts apparently unreadable, which remind of the babble of a baby.

The presentation of all these new ideas brings into the scene the defamiliarization of the old forms. Many authors consider the best way of expressing novelties in poetry departs from breaking with tradition. The best way to do so is by employing three techniques that will become very popular among contemporary writers:

– No establishing differences between prose and poetry.

– Semantic split.

– Syntactic disruption.

Breaking the frontier between prose and poetry has always been one of the fundamental characteristics employed by poets who confronted the Establishment. From the 19th century, poets popularized the use of a type of poetic composition denominated “prose-poetry” that is still very popular nowadays. It consists of a poem eminently written in prose, but that keeps the characteristics we expect from a poem. It can contain rhyme, rhythm, musicality, and rhetorical figures, as it is usual in any poetic composition.

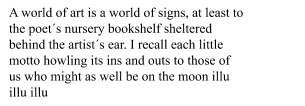

The following poem, taken from Susan Howe´s work, Debths (2017) exemplifies this quite well.9

Using a quasi metapoetic language, the author reflects on the musicality poetry contains using, paradoxically, a prose text.

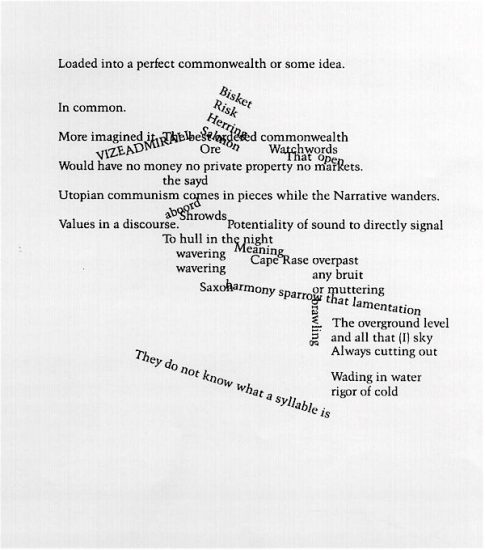

Other available technique poets employ quite frequently is what we have denominated as “semantic split.”It consists of breaking all coherent, meaningful relationships within the sentences that constitute a poem. They are just connected by juxtaposition but not by meaning. In the following poem, we have an example of how this technique works.

Visually it is constituted by a kind of collage in which sentences appear distributed on the page. Some keep the traditional location on the left margin of the page, but the majority move in all directions. The reader even gets the impression it contains a mixture of prose and verse in the same composition.

From a semantic point of view, the poem is composed of sentences and expressions that are correct grammatically speaking, but that open many questions to the reader. What relationship exists among, for example, “Values in a discourse,” “Would have no money no private property no markets,” and “Utopian communism comes in pieces while the narrative wanders” is a great unknown the reader has to solve. In this sense, the poem resembles an abstract picture. All the pieces are on it, but the reader has to make meaning from the chaos. Nevertheless, sometimes, that task becomes almost impossible to achieve, as we have already commented.

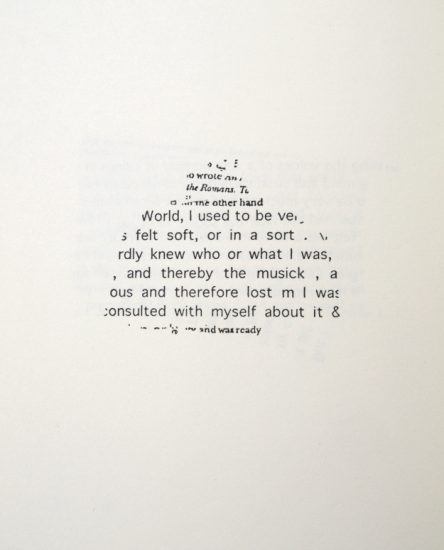

We have denominated “syntactic disruption” to the last technique, which keeps some characteristics in common with the previous one. The poet also provokes disruptions and interruptions in the text, but at the formal level. It affects word order and spelling. The poet breaks with the usual order of the sentence, eliminates connectors and even mutilates certain words or alters their spelling. It can also be accompanied by dispersion of lines on the surface of the page. It is characteristic of this technique the use of beautiful visual compositions, as we can observe in the following example.

In a tribute to tradition, the following poem is located in the center of the page, but its presentation has nothing to do with all forms. It is made by at least three fragments of texts overlapped and fragmented. There are many incomplete words, many incomplete sentences, and even some archaisms like the word “musick”.

It is evident from all these elements, Howe´s interest is not in the words but in the visual presentation they get and the way her poem exceeds all reader´s expectations. The meaning is not in the words the poem contains but in the way they are arranged, in the way they question the reader and make them look beyond the written text. The poem opens the way to multiple interpretations acquiring great importance its disposition on the page. It is like a window, an eye that observes the reader in the whiteness of all that empty space, a good metaphor of the feminine figure hidden beyond the veil of history, if we follow the literary interests of Susan Howe´s work.

It is important to notice these techniques are not used in isolation. It is possible we find all of them employed in the same poem as they are some of the most frequent characteristics contemporary poets apply to their works.

Reading Strategies

No poem is totally unreadable. Every author has in their mind the way to read and interpret their creation. The problem is the reader is not in the writer´s mind and feels there are certain poetic works that are terrible opaque and impossible to decipher. We believe in the idea that there is not just one interpretation but a lot of them, and it is the reader´s task to find theirs. With the purpose of easing that task, we have gathered several strategies that could be applied to the analysis of contemporary poetry. We have denominated them: “Alphabet Soup,” “One for All” and “Going Beyond.”

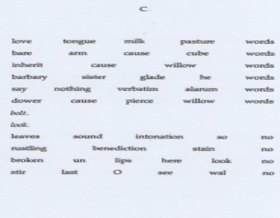

“Alphabet Soup” is applicable to those poems that seem to be constituted by long lists of words, where the presence of a sentence is something unusual or rare. The technique consists of establishing relationships between the different words looking for common characteristics: same semantic fields, same linguistic category, or some possible relationship with extra-textual sources.

In poems like this one, the reader needs to rely on elements contained in the same book as support for their interpretation. The title of the book, the section the poem is located in are aspects that can be very helpful when there seems to be so few information contained in the text. On this occasion, the poem appears preceded by the letter “C,” and curiously, in the book it is included, there is a section entitled “Book of Cordelia,” so the “C” could be the first clue to know what it is about.

As we also said previously, the reader can rely on the association of terms with elements in common. In this poem, there seem to be several words referred to the countryside as it is the case of “milk,” “pasture,” “willow,” and “leaves” which could locate the action in a country area. Something similar happens with another group of terms: “intonation,” “rustling,” “benediction,” “stain,” “lips,” and “wal”. They point to a religious service, probably a funeral, if we take into consideration all those terms that suggest silences and words in a low voice. And the last group would be that related to Cordelia, daughter of King Lear, which would include words like “love”, “cause”, “inherit”, “sister”, “he”, “say”, “nothing”, “broken” and “pierce”. They are a fragmented summary of a tragedy, a sister who did say nothing to his father´s request and broke his heart and lost her inheritance. Joining all the clues, the reader could imagine the poem is Howe´s recreation of an ancient myth using a modern presentation where the fragments remind of two aspects. In the first place, they remember the reader history is made of particles, of incomplete pieces of information that are not always reliable. In the second place, the fragmentation contained in the poem corresponds with Howe´s picture of Cordelia´s life. It is just made of pieces, of ideas, but her voice, her story is silenced in the blank spaces of history.

We have denominated the second strategy, “One for All,” and it would be applicable to poems where there is a slight fragmentation, where the reader can still rely on the poem because there are still readable sentences that provide information. The strategy would consist of choosing just two or three terms and build an interpretation of the poem on them. Once more, we will insist that, like in the previous case, the reader will probably have to rely on information from the same book or even from external sources. We will see a practical application of this strategy in this other poem.

The selection of terms would depend on the reader. As an example, we have selected just the words “The Child of Atsumori,” “Maternal Image,” and “Double play of double meaning,” being probably this last one the key for interpreting the poem. Two elements coexist in the poem, a famous play of the Noh´s theatre and an autobiographical remembrance of the poet. The “Maternal image” could be the remembrance she keeps of representing plays with her mother, and the reference to a play of this type of theatre points in the direction of a play Howe described when she was a child and that she echoes in this one.12 With just these elements, the reader could get into the poem and understand most of it without the most significant difficulties.

Our last strategy, denominated “Going Beyond,” expresses in its name its main characteristics. There are occasions the poems seem incomprehensible, and the reader is unable to extract any meaning from it. Then, the only option the reader is left is looking beyond the written words, looking for some sense, not in the text, but in what the text suggests. Here we have an excellent example of it.

In a poem like this, the reader finds a couple of legible expressions: “Author” and “Liberty.” The rest of the text is unreadable. But probably those two words and the visual presentation of the text suggest an interpretation. Texts that overlap imply authority, some restriction to the freedom of expression, that “Liberty” of an “Author” the poem refers to. If we also apply Howe´s interest for the feminine figure, we could imagine she could be referring to all those women writers whose work was silenced by men who exorcised their power on them and restricted their freedom. And this is just one of the multiple interpretations we could obtain from just a fragmented poem like this.

Conclusions

Summing up, we could say that the poetic sphere has changed a lot in the last years and that the reader is no longer a passive entity awaiting from the poet to illuminate them with their message. Now, the poem is addressed to a vast and heterogeneous audience that decides which level of implication (deep or superficial) they wish to take to approach the poetic work. In addition to that, we have to recognize contemporary poetry is making use of materials coming from a multitude of sources (history, science, literature, culture, social events, mass media, etc.) whose presentation in the text carries an important defamiliarization that obliges the reader to take an active participation in order to make sense of what seems to be a terrible chaos.

The purpose of the poem has also changed. It is no longer conceived as an object to produce aesthetic pleasure. On the contrary, in the last years, poetry has been acquiring meaningful social and political engagements. Many writers wish to awake consciousness, provoking reader´s reactions against events they want to denounce. It is particularly important the role feminism is acquiring and how many writers deal with different aspects of women´s lives in their works. But most of them break with traditional patterns to present these thematic lines which implies many readers consider this poetry unreadable and chaotic. That is the reason we have decided to provide a practical approach to the question, giving readers some tools they can use when approaching contemporary poetry.

Notes

1 There are many exciting writers in the historical period we are referring to. However, most of the examples we are going to introduce in our analysis will belong to Susan Howe. The reason is that we consider her as one of the most experimental poets of our time. From all the existing writers she is one of the best to exemplify the disruption between form and content while she surprises to the reader with a particular thematic line based on history, literature, religion, diaries, personal correspondence, and autobiography, whose content is presented in such a form the reader gets always surprised by its originality as we will see through our article.

2 in traditional poetry, there seemed to be a continuation between form and content. Poems adapted to specific metrical patterns and contained excellent thematic lines. The reader was considered just a receiver of a message transmitted by a poet who used a supposedly prescribed code. However, the reader loses all these references when there is a drastic change in the presentation of the poem, both at the level of form and content. The reader is left with an incoherent text, uncertain how to decipher it at first sight.

3 I’ll employ the term “contemporary poetry” to refer to those works produced at the period which covers the end of the 20th century (starting in the ´80s) to the present day. We are not going to classify these works into a specific group or category because we are conscious of the difficulty to trace unique common elements in such a heterogeneous group of artists.

4 My analysis will try to prove there has been an essential change in poetry, mainly in the one produced during the 20th and 21st centuries. For that reason, I’ll employ two main terms to refer to those periods. “Traditional poetry” which will refer to the classical poetry in the way it was initially conceived, with its metrical patterns, rhythm, and contents. Furthermore, the term “contemporary poetry,” which will be centered in most modern poetry, produced at the end of the 20th century, characterized by highly innovative techniques and contents.

5 Howe, That This, p. 46.

6 I refer to the first section of her poem that reads: “England´s Black Tribunal: Containing the Complete Tryal of King Charles The First by the Pretended High Court of Justice in Westminster-Hall, begun Jan. 20, 1648. Together with his Majesty´s Speech on the Scaffold, erected at Whitehall-Gate.” This is the title of a book published after Charles´s the First death as a homage to the king. Part of the text Howe reproduces in the prose sections are also a literal copy of such books, in a manifestation of her particular use of intertextuality in her works.

7 See, for example, the works of Susan Howe and David Grubbs: Thieft (2005), Souls of the Labadie Tract (2007) and Frolic Architecture (2011); the work of Jared Smith, Seven Minutes Before the Bombs Drop (2005), or Sher Christian and John Christian´s Sweet Tongue (2007), among others.

8 These photographs are courtesy of Scott Ponik, one of the members of the staff responsible for the Yale Union.

9 Howe, Debths, p. 27.

10 Howe, That This, p. 28.

11 Howe, The Europe of Trusts, p. 208.

12 In her book Pierce-Arrow, Howe uses a personal photograph of her participation in the play The Trojan Women represented at the Buckingham School in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1947.

13 Howe, That This, p. 42.

14 Howe, That This, p. 42.

Bibliography

Berman, Art. (1988) From the New Criticism to Deconstruction: The Reception of Structuralism and Post- Structuralism. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Dacey, Philip and David Jauss.(1986) Strong Measures: Contemporary American Poetry in Traditional Forms. New York: Harper and Row.

D´haen, Theo and Pieter Vermeulen, ed. (2006) Cultural Identity and Postmodern Writing. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Editions Rodopi B.V.

Finch, Annie and Katherine Varnes. (2002) An Exaltation of Forms: Contemporary Poets Celebrate the Diversity of Their Art. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Furniss, Tom and Michael Bath. (2007) Reading Poetry: An Introduction. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Limited.

Jenkins, Grant Matthew. (2008) Poetic Obligation: Ethics in Experimental American Poetry After 1945. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Hanaver, David Ian and Dyanne Rivers. (2004) Poetry and the Meaning of Life: Reading and Writing Poetry in Language Arts Classrooms. Toronto: Pippin Publishing Corporation.

Howe, Susan. (1989) A Bibliography of the King´s Book, or Eikon Basilike. Providence: Paradigm.

Howe, Susan. (1990) The Europe of Trusts. Los Angeles: Sun and Moon.

Howe, Susan. (2002) Kidnapped. Tipperary: Coracle.

Howe, Susan. (2010) That This. New York: New Directions Book.

Howe, Susan. (2013) Tom Tit Tot. Portland, Oregon: Yale Union.

Howe, Susan and David Grubbs. (2005) Thieft. (CD) Canada: Blue Chopsticks.

Howe, Susan and David Grubbs. (2007) Souls of the Labadie Tract. (CD) Canada: Blue Chopsticks.

Howe, Susan and David Grubbs. (2011) Frolic Architecture. (CD) Canada: Blue Chopsticks.

Iser, Wolfgang. (1993) Prospecting: From Reader Response to Literary Anthropology. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Novak, Julia. (2011) Live Poetry: An Integrated Approach to Poetry in Performance. The Netherlands: Rodopi.

Pfeiler, Martina. (2003) Sounds of Poetry: Contemporary American Performance Poets. Tübingen: Gunter Narr.

“poetry”. Merriam-Webster.com. 2019. http://www.merriam-webster.com (1 October 2019).

Rosenblatt, Louise M. (1978) The Reader, the Text, the Poem: the Transactional Theory of the Literary Work. Illinois, IL: Southern Illinois University.

Rovira, James, ed. (2019) Reading as Democracy in Crisis: Interpretation, Theory, History. London: Lexington Books.

Scholes, Robert. (1974) Structuralism in Literature: An Introduction. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Strachan, John and Richard Terry. (2011) Poetry. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Tompkins, Jane P., ed. (1980) Reader-Response Criticism from Formalism to Structuralism. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

Travis, Molly Abel. (1998) Reading Cultures: The Construction of Readers in the Twentieth Century. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Trawick, Leonard M., ed. (1990) World, Self, Poem: Essays on Contemporary Poetry from the “Jubilation of Poets.” Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press.

Wolosky, Shira. (2001) The Art of Poetry: How to Read a Poem. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

November 11-12, 2019, Oxford (UK).

Leave a Reply